Lucas Debargue, Piano

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4802170-Ccf435-053479213624.Pdf

1 Suite for Viola and Piano, Op. 8 - Varvara Gaigerova (1903-1944) 1. I. Allegro agitato 2:36 2. II. Andantino 3:06 3. III. Scherzo: Prest 4:25 4. IV. Moderato 4:47 Two Pieces for Viola and Piano, Op.31 - Alexander Winkler (1865-1935) 5. I. Méditation élégiaque (Andante mesto poco mosso) 4:22 6. II. La toupie: scène d’enfant: Scherzino (Allegro vivace) 2:44 Sonata in D Major for Viola and Piano, Op. 15 - Paul Juon (1872-1940) 7. I. Moderato 7:09 8. II. Adagio assai e molto cantabile 6:13 9. III. Allegro moderato 6:50 Sonata in C minor for Viola and Piano, Op. 10 - Alexander Winkler (1865-1935) 10. Moderato 9:59 11. Allegro agitato 6:28 12. L’istesso tempo ma poco rubato 4:24 Variations sur un air breton 13. Thème: Andante 1:06 14. Variation 1: L’istesso tempo poco rubato 1:39 15. Variation 2: Allegretto 1:06 16. Variation 3: Allegro patetico 1:10 17. Variation 4: Andante molto espressivo 1:23 18. Variation 5: Allegro con fuoco 1:18 19. Variation 6: Andante sostenuto 1:47 1 20. Variation 7: Fuga (Allegro moderato) 1:50 21. Coda: Poco più animato - Maestoso pesante 1:05 Total Time 71:02 In the early 20th century, composers Varvara Gaigerova, Alexander Winkler, and Paul Juon, reflect different aspects of Russian music at this historic time of intense social and political revolution. The Russian Revolution of 1905, the February and October Revolutions of 1917, in concert with the complex dynamics involved in the two great World Wars, created instability and hardship for most. -

ANATOLY ALEXANDROV Piano Music, Volume One

ANATOLY ALEXANDROV Piano Music, Volume One 1 Ballade, Op. 49 (1939, rev. 1958)* 9:40 Romantic Episodes, Op. 88 (1962) 19:39 15 No. 1 Moderato 1:38 Four Narratives, Op. 48 (1939)* 11:25 16 No. 2 Allegro molto 1:15 2 No. 1 Andante 3:12 17 No. 3 Sostenuto, severo 3:35 3 No. 2 ‘What the sea spoke about 18 No. 4 Andantino, molto grazioso during the storm’: e rubato 0:57 Allegro impetuoso 2:00 19 No. 5 Allegro 0:49 4 No. 3 ‘What the sea spoke of on the 20 No. 6 Adagio, cantabile 3:19 morning after the storm’: 21 No. 7 Andante 1:48 Andantino, un poco con moto 3:48 22 No. 8 Allegro giocoso 2:47 5 No. 4 ‘In memory of A. M. Dianov’: 23 No. 9 Sostenuto, lugubre 1:35 Andante, molto cantabile 2:25 24 No. 10 Tempestoso e maestoso 1:56 Piano Sonata No. 8 in B flat, Op. 50 TT 71:01 (1939–44)** 15:00 6 I Allegretto giocoso 4:21 Kyung-Ah Noh, piano 7 II Andante cantabile e pensieroso 3:24 8 III Energico. Con moto assai 7:15 *FIRST RECORDING; **FIRST RECORDING ON CD Echoes of the Theatre, Op. 60 (mid-1940s)* 14:59 9 No. 1 Aria: Adagio molto cantabile 2:27 10 No. 2 Galliarde and Pavana: Vivo 3:20 11 No. 3 Chorale and Polka: Andante 2:57 12 No. 4 Waltz: Tempo di valse tranquillo 1:32 13 No. 5 Dances in the Square and Siciliana: Quasi improvisata – Allegretto 2:24 14 No. -

The Fourteenth Season: Russian Reflections July 15–August 6, 2016 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Experience the Soothing Melody STAY with US

The Fourteenth Season: Russian Reflections July 15–August 6, 2016 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Experience the soothing melody STAY WITH US Spacious modern comfortable rooms, complimentary Wi-Fi, 24-hour room service, fitness room and a large pool. Just two miles from Stanford. BOOK EVENT MEETING SPACE FOR 10 TO 700 GUESTS. CALL TO BOOK YOUR STAY TODAY: 650-857-0787 CABANAPALOALTO.COM DINE IN STYLE Chef Francis Ramirez’ cuisine centers around sourcing quality seasonal ingredients to create delectable dishes combining French techniques with a California flare! TRY OUR CHAMPAGNE SUNDAY BRUNCH RESERVATIONS: 650-628-0145 4290 EL CAMINO REAL PALO ALTO CALIFORNIA 94306 Music@Menlo Russian Reflections the fourteenth season July 15–August 6, 2016 D AVID FINCKEL AND WU HAN, ARTISTIC DIRECTORS Contents 2 Season Dedication 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 4 Welcome from the Executive Director 4 Board, Administration, and Mission Statement 5 R ussian Reflections Program Overview 6 E ssay: “Natasha’s Dance: The Myth of Exotic Russia” by Orlando Figes 10 Encounters I–III 13 Concert Programs I–VII 43 Carte Blanche Concerts I–IV 58 Chamber Music Institute 60 Prelude Performances 67 Koret Young Performers Concerts 70 Master Classes 71 Café Conversations 72 2016 Visual Artist: Andrei Petrov 73 Music@Menlo LIVE 74 2016–2017 Winter Series 76 Artist and Faculty Biographies A dance lesson in the main hall of the Smolny Institute, St. Petersburg. Russian photographer, twentieth century. Private collection/Calmann and King Ltd./Bridgeman Images 88 Internship Program 90 Glossary 94 Join Music@Menlo 96 Acknowledgments 101 Ticket and Performance Information 103 Map and Directions 104 Calendar www.musicatmenlo.org 1 2016 Season Dedication Music@Menlo’s fourteenth season is dedicated to the following individuals and organizations that share the festival’s vision and whose tremendous support continues to make the realization of Music@Menlo’s mission possible. -

Kabalevsky Was Born in St Petersburg on 30 December 1904 and Died in Moscow on 14 February 1987 at the Age of 83

DMITRI KABALEVSKY SIKORSKI MUSIKVERLAGE HAMBURG SIK 4/5654 2 CONTENTS FOREWORD by Maria Kabalevskaya ...................... 4 VORWORT ....................................... 6 INTRODUCTION by Tatjana Frumkis .................... 8 EINFÜHRUNG .................................. 10 AWARDS AND PRIZES ............................ 13 CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF WORKS .............. 15 SYSTEMATIC INDEX OF WORKS Stage Works ..................................... 114 Orchestral Works ................................. 114 Instrumental Soloist and Orchestra .................... 114 Wind Orchestra ................................... 114 Solo Voice(s) and Orchestra ......................... 115 Solo Voice(s), Choir and Orchestra .................... 115 Choir and Orchestra ............................... 115 Solo Voice(s), Choir and Piano ....................... 115 Choir and Piano .................................. 115 Voice(s) a cappella ................................ 117 Voice(s) and Instruments ............................ 117 Voice and Piano .................................. 117 Piano Solo ....................................... 118 Piano Four Hands ................................. 119 Instrumental Chamber Works ........................ 119 Incidental Music .................................. 120 Film Music ...................................... 120 Arrangements .................................... 121 INDEX Index of Opus Numbers ............................ 122 Works Without Opus Numbers ....................... 125 Alphabetic Index of Works ......................... -

Sposobin Remains. a Soviet Harmony Textbook's Twisted Fate in China

Sposobin Remains A Soviet Harmony Textbook’s Twisted Fate in China1 Wai Ling Cheong, Ding Hong In 1937–38, Igor V. Sposobin and three co-authors at the Moscow Conservatory published Uchebnik garmonii [Harmony Textbook]. This was the first officially approved harmony textbook in the USSR, which came to be adopted as “the basic textbook for courses on harmony in the mu- sic schools of the Soviet Union” (Vladimir Protopopov, 1960). Characterized by its promulgation of the “scientifically based” theory of harmonic functions, this book was destined to be read by many more musicians in a foreign land. In 1955–56, Boris A. Arapov decreed at meetings held at the Central Conservatory of Music in China that the problem posed by the ethnicization of harmo- ny should be solved by combining musical elements that are considered ethnically distinct with functional harmony. Wu Zuqiang, who had studied at the Moscow Conservatory in the 1950s before he headed the Central Conservatory in the 1980s, published a chapter from Uchebnik garmonii already in 1955. The first Chinese translation of the whole book by Zhu Shimin was then published in 1957–58. The book soon attained canonic status in China and has been used in vir- tually all Chinese music institutions up to the present day. It is listed in the entrance examination syllabi of selected conservatories and reputable music theorists have published model answers to the exercises it contains. This article investigates how the Chinese reception of Uchebnik garmonii diverges from the sources that had inspired Sposobin and his colleagues to compose it in the first place, and throws light on the far-reaching impacts and ramifications of Uchebnik garmonii in China. -

Harmonic Functionalism in Russian Music Theory: a Primer

Harmonic Functionalism in Russian Music Theory: A Primer Philip Ewell Hunter College CUNY It is often noted that Russian music theory relies heavily on the theories of Hugo Riemann. At the same time, it is also noted that those of Heinrich Schenker have had virtually no currency in Russia. Tis should come as no surprise insofar as Schenker was such an inveterate anticommunist and anti-Marxist. Perhaps because of Russia’s Schenkerian void, the history of step theory (Stufentheorie), in which Schenker serves as something of a culmination, rarely gets told. Yet Russia has a rich and long tradition with step theory, one that has always been part of its music theory. In fact, as I show below, many signifcant Russian music-theoretical works represent a hybrid of the two main harmonic systems that emerged from 18th and 19th-Century European practices, step theory and function theory (Funktionstheorie). Riemann is generally considered the most well-known fgure in the history of function theory—after all, it was he who took the word “function,” from mathematics, and applied it to musical chords. But his work did not arise in a vacuum of course. Tere were important precursors to his work. Te story of how Riemann’s work made it to Russia is generally underexplored, with the outstanding work of Ellon Carpenter in the 1980s the exception.1 In examining harmonic functionalism in Russian music theory here, I follow in her footsteps. I will look at three main fgures in my music-theoretical primer: Nikolai Rimsky- Korsakov, Georgy Catoire, and Yuri Tiulin. -

Georgy Catoire & Ignaz Friedman

GEORGY CATOIRE & IGNAZ FRIEDMAN PIANO QUINTETS NILS-ERIK SPARF violin ULF FORSBERG violin ELLEN NISBETH viola ANDREAS BRANTELID cello BENGT FORSBERG piano BIS-2314 CATOIRE, Georgy (1861–1926) Piano Quintet in G minor, Op. 28 (1914) 24'21 1 I. Allegro moderato 8'18 2 II. Andante 8'32 3 III. Allegro con spirito e capriccioso 7'19 FRIEDMAN, Ignaz (1882–1948) Piano Quintet in C minor (1918) (Edition Wilhelm Hansen) 36'58 4 I. Allegro maestoso 14'46 5 II. Larghetto, con somma espressione 13'46 6 III. Epilogue. Allegretto semplice 8'17 TT: 62'08 Bengt Forsberg piano Nils-Erik Sparf violin I Ulf Forsberg violin II Ellen Nisbeth viola Andreas Brantelid cello 2 musical genre in its own right or just a sub-category of chamber music? The quintet for piano and strings certainly enjoys a special status, to judge A by the stature of works composed for this combination of instruments. But precisely which combination are we referring to? At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the piano was certainly to be found in the company of four string instruments – but they were a violin, a viola, a cello and a double bass. It was prob - ably Jan Ladislav Dussek who wrote the first work for such an ensemble, but it was Franz Schubert who had the honour of writing the first masterpiece: the famous ‘Trout’ Quintet (1819). As for the combination of piano and a ‘classical’ string quartet (two violins, viola and cello), although Boccherini set the ball rolling at the end of the eighteenth century, it was really with Robert Schumann and his Op. -

A1 CATOIRE Piano Music • Marc-André Hamelin

A1 CATOIRE Piano Music • Marc-André Hamelin (pn) • HYPERION CDA67090 (77:59) Caprice, op. 3. Intermezzo, op. 6. 3 Morceaux, op. 2. Prélude, op 6/2. Scherzo, op. 6/3. Vision (Étude); op. 8. 5 Morceaux, op. 10. 4 Morceaux, op 12 4 Préludes, op 17 Chants du crépuscule, op. 24. Poème, op. 34/2. Prélude, op. 34/3. Valse, op. 36 Who? Georges (Georgy) L'vovich Catoire (1861-1926) is one of the forgotten men of music. Even for specialists in Russian music he is a vaguely remembered name rather than a composer whose music actively leaps to the inner ear. Moscow-born, Catoire was a good enough pianist at the age of 14 to take lessons from Karl Klindworth; he studied in Berlin in his mid-twenties, and returned to Russia in 1887, to take further instruction from Rimsky-Korsakov and Liadov. Thereafter, he settled down to explore on his own. If you want a swift style guide, imagine Lyapunov, not in Lisztian mode but in the school that would soon lead to Medtner and Rachmaninov. Lyapunov, indeed, was Catoire's teacher for a while, but I had made the connection aurally before I read about the relationship in Robert Matthew-Walker's excellent accompanying essay with this release. Another readily identifiable influence is the Grieg of the Lyric Pieces, again confirmed by Matthew- Walker, who also writes, "Catoire's approach to harmony was typical of composers of his generation in that he found the expansion of tonality in the latter years of the nineteenth century—through the growth of chromaticism and a greater tonal freedom in the relationship of certain keys, particularly in Catoire's case the subdominant and the supertonic, to the tonic—both liberating and fruitful areas to explore." I'm slightly surprised, because I find the harmonic aspects of this music among its most conventional characteristics. -

A Dictionary for the Modern Pianist DICTIONARIES for the MODERN MUSICIAN

A Dictionary for the Modern Pianist DICTIONARIES FOR THE MODERN MUSICIAN Series Editor: Jo Nardolillo Contributions to Dictionaries for the Modern Musician series offer both the novice and the advanced artist lists of key terms designed to fully cover the field of study and performance for major instruments and classes of instruments, as well as the workings of musicians in areas from composing to conducting. Focusing primarily on the knowledge required by the contemporary musical student and teacher, performer, and professional, each dictionary is a must-have for any musician’s personal library! All Things Strings: An Illustrated Dictionary by Jo Nardolillo, 2014 A Dictionary for the Modern Singer by Matthew Hoch, 2014 A Dictionary for the Modern Clarinetist by Jane Ellsworth, 2014 A Dictionary for the Modern Trumpet Player by Elisa Koehler, 2015 A Dictionary for the Modern Conductor by Emily Freeman Brown, 2015 A Dictionary for the Modern Pianist by Stephen Siek, 2016 A Dictionary for the Modern Pianist Stephen Siek ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London Published by Rowman & Littlefield A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB Copyright © 2017 by Rowman & Littlefield All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Siek, Stephen, author. -

TOCC0093DIGIBKLT.Pdf

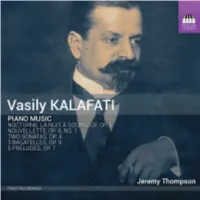

THE PIANO MUSIC OF VASILY KALAFATI by Jonathan Powell If Vasily Pavlovich Kalafati (1869–1942) surfaces in music history at all, he gets a mention as one of Stravinsky’s earliest teachers, or might appear among a list of the students of Rimsky-Korsakov, or the composers published by the maecenas Mitrofan Belaieff. Recently, though, as scholars1 and performers become interested in his work, more details emerge about this composer with an intriguing, partly Russified Greek name (originally Βασίλης Καλαφάτης), and one who, it seems, was a figure of some repute in the musical life of early-twentieth-century St Petersburg. From the beginning of the nineteenth century, foreigners and Russians of mixed parentage had played key roles in Russian musical life, starting with John Field, then Adolf von Henselt, and continuing with César Cui, Eduard Nápravník, Georgy Catoire, the Conus family and numerous others. While Kalafati ‘always considered himself G r e e k’, 2 and spent most of his life in Russia (barring brief trips abroad), he was certainly not alone as a non-Russian student at the St Petersburg Conservatoire in the 1890s. He was one among many who came from the outer reaches, or beyond the limits, of the Russian empire to study with Rimsky-Korsakov, whose cosmopolitan class, over a 35-year period, consisted of students from not only Russia but also Armenia, Azerbaijan, Italy (Respighi), Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Ukraine. 1 Most notably Stanimira Dermendzhieva, who completed her Ph.D. thesis – Vasily Pavlovich Kalafati (1869–1942): The Life and Works of the Forgotten Composer and Teacher of Russia, Ionian University, Corfu, 2012 – and whom I heard present her paper ‘Vasily Kalafati: Early Works and Study at the St Petersburg Conservatory with Rimsky-Korsakov’ at a 2010 conference in St Petersburg, ‘N. -

Georgy Catoire Works for Violin & Piano Laurent Albrecht Breuninger I Anna Zassimova "

_______________ -------------- ••• '"I:!" @fOlD Georgy Catoire Works for Violin & Piano Laurent Albrecht Breuninger I Anna Zassimova " 1 Anna Zassimova cpo 777 378 - 2 __________________ ===::::;:,=====--==========II-~-= ••------------------ Georgy Catoire (1861-1926) Works for Violin & Piano Sonata for Violin & Piano No.1 op.1S in B minor 34'58 16'12 IT] Allegro non tanto, me apassionato 8'22 IT] Barcarole. Andante 10'16 [2] Allegro con spirito 8] Poeme for Violin & Piano op. 20 in D major 22'45 (2nd Sonata) Andante - Allegra - Moderato [}] Elegie for Violin & Piano op. 26 5'06 Andante o Romanze for Alto & Piano op. 1 No.4, 3'32 Version for Violin & Piano Moderato T.T.:66'21 Laurent Albrecht Breuninger, Violin Laurent Albrecht Breuninger Anna Zassimova, Piano Georges (Jegor l'vovic) Catoire Moskauer Konservatorium. Ober diesen wird er mit der bevor er sich bald wieder fest in Moskau ansiedelt. Mit Dos Werk yon Georges Catoire enthalt Charakteri• (1861-1926) Musik Wagners vertraut, die dem russischen Publikum dieser Zeit beendet er dann auch seine Studien und 10Bt stika, die sich interessanterweise immer etwas ausser· damals noch kaum bekannt war und die yon den nam• sich nur noch bei Bedarf yon den befreundeten Mos• halb der jeweiligen Stromungen seiner Zeit entwickel· Am 27. Oktober 1885 schreibt P. Tschaikowskij, haften Musikern im land Oberwiegend abgelehnt kauer Komponisten, wie beispielsweise Taneev und ten, und schon daher besondere Aufmerksamkeit auf nach der ersten Begegnung ·mit dem damols 24-jahri• wurde. Catoire besucht die Bayreuther Festspiele, tritt Arenskij beraten. Er hat jetzt zu einer ganz eigenen sich zieht. gen Georges (Georgi;, Jegor L'vovic) Catoire, der Wagner-Gesellschaft bei und kann als erster russi• musikalischen Sprache gefunden und um die Jahrhun• Seine Kompositionen vereinen Neuerungen in der an Nadezda von Mekk: "Wie ich Ihnen ja vermutlich scher "Wagnerianer" bezeichnet werden. -

Interpreting Polyphony in Russian/Soviet Piano Transcriptions of J

Reconciling the analyst and the performer: Interpreting polyphony in Russian/Soviet piano transcriptions of J. S. Bach’s works Nadezhda Koudasheva A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Sydney Conservatorium of Music, The University of Sydney 2019 Declaration The dissertation presented here is the result of my own work and does not include collaboration unless otherwise stated. It has not previously been submitted for any degree or qualification. The transcription list presented in the appendix builds on a list the compilation of which I commenced during my B. Mus. Honours project (2014, University of Sydney). ii Abstract Attempts to analyse polyphonic textures from a score can result in controversially different conclusions. By drawing on questions which arise from analysing Russian/Soviet piano transcriptions of works of J. S. Bach this study demonstrates how some conclusions made about polyphonic texture from a score are effectively descriptions of an imagined performance by the analyst. Many factors defined in a performance influence the analyst’s decision to note the presence of polyphonic features such as inferred melodies. The value of realising that an analyst is effectively an analyst-performer becomes particularly evident when attempting to analyse Bach transcriptions. Aside from discussing analytical methods, the underlying aim of this study is to draw attention to the extensive tradition of Russian/Soviet piano transcriptions of works of J. S. Bach which spans from the first half of the 19th century to today and includes over 250 transcriptions by dozens of transcribers. The relevant scores and texts were either accessed from libraries and archives in Russia or sourced online.