Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer (2Nd Edition)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WARM WARM Kerning by Eye for Perfectly Balanced Spacing

Basic typographic principles: A guide by The Typographic Circle Glossary of basic terms Typeface The overall design of a type family Gill Sans Univers Georgia Gill Sans, Univers & Georgia are all typefaces. Font Referring back to when type was cast in molten You’ll see that a typeface can come in various metal using a mould, or font. A font is how a types of digital font; such as OpenType, TrueType typeface is delivered. So you can have both a metal and Postscript fonts. Each have different reasons handmade font and a digital font file of the same for being, but they are essentially just different typeface, e.g Times or Futura. ways of delivering the same typeface. Serif Short strokes at the ends of horizontal and vertical Times strokes of characters. Generally considered to be Hoefler Text easier to read for large quantities of text, and often, Baskerville but not always, associated with more traditional Minion and older themes. Georgia Sans Serif Taken from the French word sans, meaning Akzidenz Grotesk ‘without’, sans serif simply means without serifs. Helvetica Generally, but not always, considered to be Univers associated with modern themes. Gotham Slab Serif A typeface with weightier, ‘slab-like’ serifs. Rockwell Lubalin Graph Uppercase CAPITAL LETTERS ABCDEFGH Lowercase non-capital letters abcdefgh Mixed-case A mix of the two above, that conforms to Great, it’ll be sunny on Saturday. the standard rules of a normal sentence. Sometimes called sentence-case. Title-case Capitalising all of the major words in a sentence. Improving your Typography: Easy with Practice There are various schools of thought as to what defines a ‘major’ word, but it tends to looks neater when connecting words like and, the, to, but, is & my remain lowercase. -

Extreme Leadership Leaders, Teams and Situations Outside the Norm

JOBNAME: Giannantonio PAGE: 3 SESS: 3 OUTPUT: Wed Oct 30 14:53:29 2013 Extreme Leadership Leaders, Teams and Situations Outside the Norm Edited by Cristina M. Giannantonio Amy E. Hurley-Hanson Associate Professors of Management, George L. Argyros School of Business and Economics, Chapman University, USA NEW HORIZONS IN LEADERSHIP STUDIES Edward Elgar Cheltenham, UK + Northampton, MA, USA Columns Design XML Ltd / Job: Giannantonio-New_Horizons_in_Leadership_Studies / Division: prelims /Pg. Position: 1 / Date: 30/10 JOBNAME: Giannantonio PAGE: 4 SESS: 3 OUTPUT: Wed Oct 30 14:53:29 2013 © Cristina M. Giannantonio andAmy E. Hurley-Hanson 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Published by Edward Elgar Publishing Limited The Lypiatts 15 Lansdown Road Cheltenham Glos GL50 2JA UK Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc. William Pratt House 9 Dewey Court Northampton Massachusetts 01060 USA A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Control Number: 2013946802 This book is available electronically in the ElgarOnline.com Business Subject Collection, E-ISBN 978 1 78100 212 4 ISBN 978 1 78100 211 7 (cased) Typeset by Columns Design XML Ltd, Reading Printed and bound in Great Britain by T.J. International Ltd, Padstow Columns Design XML Ltd / Job: Giannantonio-New_Horizons_in_Leadership_Studies / Division: prelims /Pg. Position: 2 / Date: 30/10 JOBNAME: Giannantonio PAGE: 1 SESS: 5 OUTPUT: Wed Oct 30 14:57:46 2013 14. Extreme leadership as creative leadership: reflections on Francis Ford Coppola in The Godfather Charalampos Mainemelis and Olga Epitropaki INTRODUCTION How do extreme leadership situations arise? According to one view, they are triggered by environmental factors that have nothing or little to do with the leader. -

CELEBRATING FORTY YEARS of FILMS WORTH TALKING ABOUT 39 Years, 2 Months, and Counting…

5 JAN 18 1 FEB 18 1 | 5 JAN 18 - 1 FEB 18 88 LOTHIAN ROAD | FILMHOUSECinema.COM CELEBRATING FORTY YEARS OF FILMS WORTH TALKING ABOUT 39 Years, 2 Months, and counting… As you’ll spot deep within this programme (and hinted at on the front cover) January 2018 sees the start of a series of films that lead up to celebrations in October marking the 40th birthday of Filmhouse as a public cinema on Lothian Road. We’ve chosen to screen a film from every year we’ve been bringing the very best cinema to the good people of Edinburgh, and while it is tremendous fun looking back through the history of what has shown here, it was quite an undertaking going through all the old programmes and choosing what to show, and a bit of a personal journey for me as one who started coming here as a customer in the mid-80s (I know, I must have started very young...). At that time, I’d no idea that Filmhouse had only been in existence for less than 10 years – it seemed like such an established, essential institution and impossible to imagine it not existing in a city such as Edinburgh. My only hope is that the cinema is as important today as I felt it was then, and that the giants on whose shoulders we currently stand feel we’re worthy of their legacy. I hope you can join us for at least some of the screenings on this trip down memory lane... And now, back to the now. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

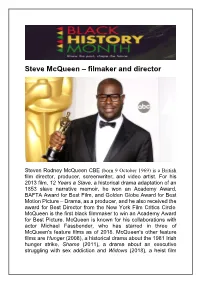

Steve Mcqueen – Filmaker and Director

Steve McQueen – filmaker and director Steven Rodney McQueen CBE (born 9 October 1969) is a British film director, producer, screenwriter, and video artist. For his 2013 film, 12 Years a Slave, a historical drama adaptation of an 1853 slave narrative memoir, he won an Academy Award, BAFTA Award for Best Film, and Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Drama, as a producer, and he also received the award for Best Director from the New York Film Critics Circle. McQueen is the first black filmmaker to win an Academy Award for Best Picture. McQueen is known for his collaborations with actor Michael Fassbender, who has starred in three of McQueen's feature films as of 2018. McQueen's other feature films are Hunger (2008), a historical drama about the 1981 Irish hunger strike, Shame (2011), a drama about an executive struggling with sex addiction and Widows (2018), a heist film about a group of women who vow to finish the job when their husbands die attempting to do so. McQueen was born in London and is of Grenadianand Trinidadian descent. He grew up in Hanwell, West London and went to Drayton Manor High School. In a 2014 interview, McQueen stated that he had a very bad experience in school, where he had been placed into a class for students believed best suited "for manual labour, more plumbers and builders, stuff like that." Later, the new head of the school would admit that there had been "institutional" racism at the time. McQueen added that he was dyslexic and had to wear an eyepatch due to a lazy eye, and reflected this may be why he was "put to one side very quickly". -

Film Essay for "Mccabe & Mrs. Miller"

McCabe & Mrs. Miller By Chelsea Wessels In a 1971 interview, Robert Altman describes the story of “McCabe & Mrs. Miller” as “the most ordinary common western that’s ever been told. It’s eve- ry event, every character, every west- ern you’ve ever seen.”1 And yet, the resulting film is no ordinary western: from its Pacific Northwest setting to characters like “Pudgy” McCabe (played by Warren Beatty), the gun- fighter and gambler turned business- man who isn’t particularly skilled at any of his occupations. In “McCabe & Mrs. Miller,” Altman’s impressionistic style revises western events and char- acters in such a way that the film re- flects on history, industry, and genre from an entirely new perspective. Mrs. Miller (Julie Christie) and saloon owner McCabe (Warren Beatty) swap ideas for striking it rich. Courtesy Library of Congress Collection. The opening of the film sets the tone for this revision: Leonard Cohen sings mournfully as the when a mining company offers to buy him out and camera tracks across a wooded landscape to a lone Mrs. Miller is ultimately a captive to his choices, una- rider, hunched against the misty rain. As the unidenti- ble (and perhaps unwilling) to save McCabe from his fied rider arrives at the settlement of Presbyterian own insecurities and herself from her opium addic- Church (not much more than a few shacks and an tion. The nuances of these characters, and the per- unfinished church), the trees practically suffocate the formances by Beatty and Julie Christie, build greater frame and close off the landscape. -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

The Holy Fool in Late Tarkovsky

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Nebraska, Omaha Journal of Religion & Film Volume 18 | Issue 1 Article 45 3-31-2014 The olH y Fool in Late Tarkovsky Robert O. Efird Virginia Tech, [email protected] Recommended Citation Efird, Robert O. (2014) "The oH ly Fool in Late Tarkovsky," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 18 : Iss. 1 , Article 45. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol18/iss1/45 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The olH y Fool in Late Tarkovsky Abstract This article analyzes the Russian cultural and religious phenomenon of holy foolishness (iurodstvo) in director Andrei Tarkovsky’s last two films, Nostalghia and Sacrifice. While traits of the holy fool appear in various characters throughout the director’s oeuvre, a marked change occurs in the films made outside the Soviet Union. Coincident with the films’ increasing disregard for spatiotemporal consistency and sharper eschatological focus, the character of the fool now appears to veer off into genuine insanity, albeit with a seemingly greater sensitivity to a visionary or virtual world of the spirit and explicit messianic task. Keywords Andrei Tarkovsky, Sacrifice, Nostalghia, Holy Foolishness Author Notes Robert Efird is Assistant Professor of Russian at Virginia Tech. He holds a PhD in Slavic from the University of Virginia and is the author of a number of articles dealing with Russian and Soviet cinema. -

CFP Refocus: the Films of Andrei Tarkovsky

H-Announce CFP ReFocus: The Films of Andrei Tarkovsky Announcement published by Sergei Toymentsev on Wednesday, August 3, 2016 Type: Call for Publications Date: November 30, 2016 Location: United States Subject Fields: Art, Art History & Visual Studies, Cultural History / Studies, Film and Film History, Humanities, Russian or Soviet History / Studies ReFocus: The Films of Andrei Tarkovsky Andrei Tarkovsky (1932 -1986) is a renowned Russian filmmaker whose work, despite an output of only seven feature films in twenty years, has had a profound influence on international cinema. Famous for languid pacing, long takes, dreamlike imagery, spiritual depth and philosophical allegories, most of his films have gained cult status among cineastes and are often included in various kinds of ranking polls and charts dedicated to the "best movies ever made." Thus, for example, the British Film Institute's "50 Greatest Films of All Time" poll conducted for the film magazine Sight & Sound in 2012 honors three of Tarkovsky's films: Andrei Rublev (1966) is ranked at No. 26, Mirror (1974) at No. 19, and Stalker (1979) at No. 29. Beginning with the late 1980, Tarkovsky's highly complex cinema has continuously attracted scholarly and critical attention in film studies by generating countless hermeneutic challenges and possibilities for film scholars. Almost all intellectual vogues and methodologies in humanities, whether it's feminism, psychoanalysis, poststructuralism, diaspora studies or film-philosophy, have left their interpretative trace on the reception of his work. This ReFocus anthology on Andrei Tarkovsky invites chapter proposals of 200-400 words that would take yet another look at the director's legacy from interdisciplinary perspectives. -

Full Cinematic Retrospective of Director Andrei Tarkovsky This Summer at MAD

Full Cinematic Retrospective of Director Andrei Tarkovsky this Summer at MAD Andrei Tarkovsky, Sculpting in Time presents the work of the revolutionary director and includes screenings—all on 35 mm—of all seven feature films and a behind-the-scenes documentary Stalker, 1976. Andrei Tarkovsky. New York, NY (June 8, 2015)—The Museum of Arts and Design presents a full cinematic retrospective of Andrei Tarkovsky’s work this summer with its latest cinema series, Andrei Tarkovsky, Sculpting in Time, from July 10 through August 28, 2015. Over the course of just seven feature films, Tarkovsky produced a poetic and enigmatic body of work that expanded the possibilities of cinema as an art form and transformed a wide range of genres including science fiction, war stories, film essays and historical dramas. Celebrating the legacy of this revolutionary director, the retrospective includes screenings of Tarkovsky’s seven feature films on 35 mm, as well as a behind-the-scenes documentary that reveals the process behind his groundbreaking practice and cinematic achievements. “Few directors have had as large of an influence on cinema as Andrei Tarkovsky,” says Jake Yuzna, MAD’s Director of Public Programs. “Working under censorship and with little support from the Soviet Union, Tarkovsky fought fiercely for his conceptualization of cinema as a singular and vital art form. Reconsidering the role of films in an age of increasing technology, Tarkovsky saw cinema as not merely a tool for communicating information, but as ‘a moral barometer in a sea of competing narratives.’” 2 COLUMBUS CIRCLE NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10019 P 212.299.7777 F 212.299.7701 MADMUSEUM.ORG Premiering on July 10 with Tarkovsky’s science fiction classic, Solaris, the retrospective showcases the director’s distinctive and influential aesthetic, characterized by expressive, sweeping takes, the evocative use of landscapes, and his method of “sculpting in time” with a camera. -

The American Film Institute and TV Land Announce the Benefit Committee for AFI Life Achievement Award: a Tribute to Morgan Freeman

The American Film Institute and TV Land Announce the Benefit Committee for AFI Life Achievement Award: A Tribute to Morgan Freeman Gala To Be Held On The Historic Sony Lot In Culver City On June 9, 2011 Show Premieres On TV Land On Sunday, June 26, 2011 At 8:00 p.m. ET/PT LOS ANGELES, April 26, 2011 /PRNewswire via COMTEX/ -- American film's finest have confirmed their participation on the American Film Institute (AFI) Gala Benefit Committee honoring 39th Life Achievement Award recipient, Morgan Freeman. Members of this year's benefit committee are Ben Affleck, Jim Carrey, Clint Eastwood, Tom Hanks, Ashley Judd, Helen Mirren, Mike Nichols, Jack Nicholson, Brad Pitt, Sidney Poitier, Robert Redford, Tim Robbins, Steven Spielberg, Hilary Swank, Denzel Washington and Alfre Woodard. AFI will present the 39th AFI Life Achievement Award - America's highest honor for a career in film - to Freeman on June 9th. "TV Land Presents: The AFI Life Achievement Award Honoring Morgan Freeman" will air on TV Land on Sunday, June 26, 2011 at 8:00 p.m. ET/PT. The black-tie event will take place on historic Stage 15 at Sony Pictures Studios, where "The Wizard of Oz," "Grand Hotel," "Spiderman" and other classic movies were filmed. The stage will be transformed into an elegant ballroom to honor the storied career of Morgan Freeman. Proceeds from the AFI Life Achievement Award Gala directly support the Institute's national educational programs and the preservation of American film history. "Morgan Freeman has embodied characters that range from prisoner to president, from gumshoe to God," said Bob Gazzale, AFI President and CEO. -

Film, Philosophy Andreligion

FILM, PHILOSOPHY AND RELIGION Edited by William H. U. Anderson Concordia University of Edmonton Alberta, Canada Series in Philosophy of Religion Copyright © 2022 by the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, Suite 1200, C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Wilmington, Delaware 19801 Malaga, 29006 United States Spain Series in Philosophy of Religion Library of Congress Control Number: 2021942573 ISBN: 978-1-64889-292-9 Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. Cover design by Vernon Press. Cover image: "Rendered cinema fimstrip", iStock.com/gl0ck To all the students who have educated me throughout the years and are a constant source of inspiration. It’s like a splinter in your mind. ~ The Matrix Table of contents List of Contributors xi Acknowledgements xv Introduction xvii William H.