Questioning Chivalry in the Middle English Gawain Romances

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queen Guinevere

Ingvarsdóttir 1 Hugvísindasvið Queen Guinevere: A queen through time B.A. Thesis Marie Helga Ingvarsdóttir June 2011 Ingvarsdóttir 2 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Enskudeild Queen Guinevere: A queen through time B.A. Thesis Marie Helga Ingvarsdóttir Kt.: 060389-3309 Supervisor: Ingibjörg Ágústsdóttir June 2011 Ingvarsdóttir 3 Abstract This essay is an attempt to recollect and analyze the character of Queen Guinevere in Arthurian literature and movies through time. The sources involved here are Welsh and other Celtic tradition, Latin texts, French romances and other works from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, Malory’s and Tennyson’s representation of the Queen, and finally Guinevere in the twentieth century in Bradley’s and Miles’s novels as well as in movies. The main sources in the first three chapters are of European origins; however, there is a focus on French and British works. There is a lack of study of German sources, which could bring different insights into the character of Guinevere. The purpose of this essay is to analyze the evolution of Queen Guinevere and to point out that through the works of Malory and Tennyson, she has been misrepresented and there is more to her than her adulterous relation with Lancelot. This essay is exclusively focused on Queen Guinevere and her analysis involves other characters like Arthur, Lancelot, Merlin, Enide, and more. First the Queen is only represented as Arthur’s unfaithful wife, and her abduction is narrated. We have here the basis of her character. Chrétien de Troyes develops this basic character into a woman of important values about love and chivalry. -

Structure, Legitimacy, and Magic in <Em>The Birth of Merlin</Em>

Early Theatre 9.1 Megan Lynn Isaac Legitimizing Magic in The Birth of Merlin Bastardy, adultery, and infidelity are topics at issue in The Birth of Merlin on every level. Unfortunately, most of the critical examination of these topics has not extended beyond the title page. In 1662 Francis Kirkman and Henry Marsh commissioned the first known printing of the play from an old manuscript in Kirkman’s possession. The title page of their version attributes the play to Shakespeare and Rowley, and generations of critics have quarreled over the legitimacy of that ascription. Without any compelling evidence to substantiate the authorship of Shakespeare and Rowley, many critics have tried to solve the dilemma from the other end. Just as in the play Merlin’s mother spends most of the first act inquiring of every man she meets whether he might have fathered her child, these scholars have attempted to attribute the play to virtually every dramatist and combination of dramatists on record. Beaumont, Fletcher, Ford, Middleton, and Dekker, among others, have all been subjected to the literary equivalent of a blood-test; analyses of their spelling and linguistic preferences have been made in an effort to link them to The Birth of Merlin.1 Unlike the hero of the drama, however, the play itself is still without a father, though it does have a birthdate in 1622, as has been demonstrated be N.W. Bawcutt.2 Debates over authorship are not particularly uncommon in early modern studies, but the question of who fathered the legendary Merlin, the topic of the play, is more unusual and more interesting. -

Reputation Systems for Anonymous Networks

Reputation Systems for Anonymous Networks Elli Androulaki, Seung Geol Choi, Steven M. Bellovin, and Tal Malkin Department of Computer Science, Columbia University {elli,sgchoi,smb,tal}@cs.columbia.edu Abstract. We present a reputation scheme for a pseudonymous peer-to-peer (P2P) system in an anonymous network. Misbehavior is one of the biggest prob- lems in pseudonymous P2P systems, where there is little incentive for proper behavior. In our scheme, using ecash for reputation points, the reputation of each user is closely related to his real identity rather than to his current pseudonym. Thus, our scheme allows an honest user to switch to a new pseudonym keeping his good reputation, while hindering a malicious user from erasing his trail of evil deeds with a new pseudonym. 1 Introduction Pseudonymous System. Anonymity is a desirable attribute to users (or peers) who par- ticipate in peer-to-peer (P2P) system. A peer, representing himself via a pseudonym, is free from the burden of revealing his real identity when carrying out transactions with others. He can make his transactions unlinkable (i.e., hard to tell whether they come from the same peer) by using a different pseudonym in each transaction. Com- plete anonymity, however, is not desirable for the good of the whole community in the system: an honest peer has no choice but to suffer from repeated misbehaviors (e.g. sending an infected file to others) of a malicious peer, which lead to no consequences in this perfectly pseudonymous world. Reputation System. We present a reputation system as a reasonable solution to the above problem. -

Introduction: the Legend of King Arthur

Department of History University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire “HIC FACET ARTHURUS, REX QUONDAM, REXQUE FUTURUS” THE ANALYSIS OF ORIGINAL MEDIEVAL SOURCES IN THE SEARCH FOR THE HISTORICAL KING ARTHUR Final Paper History 489: Research Seminar Professor Thomas Miller Cooperating Professor: Professor Matthew Waters By Erin Pevan November 21, 2006 1 Copyright for this work is owned by the author. This digital version is published by McIntyre Library, University of Wisconsin – Eau Claire with the consent of the author. 2 Department of History University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire Abstract of: “HIC FACET ARTHURUS, REX QUONDAM, REXQUE FUTURUS” THE ANALYSIS OF ORIGINAL MEDIEVAL SOURCES IN THE SEARCH FOR THE HISTORICAL KING ARTHUR Final Paper History 489: Research Seminar Professor Thomas Miller Cooperating Professor: Matthew Waters By Erin Pevan November 21, 2006 The stories of Arthurian literary tradition have provided our modern age with gripping tales of chivalry, adventure, and betrayal. King Arthur remains a hero of legend in the annals of the British Isles. However, one question remains: did King Arthur actually exist? Early medieval historical sources provide clues that have identified various figures that may have been the template for King Arthur. Such candidates such as the second century Roman general Lucius Artorius Castus, the fifth century Breton leader Riothamus, and the sixth century British leader Ambrosius Aurelianus hold high esteem as possible candidates for the historical King Arthur. Through the analysis of original sources and authors such as the Easter Annals, Nennius, Bede, Gildas, and the Annales Cambriae, parallels can be established which connect these historical figures to aspects of the Arthur of literary tradition. -

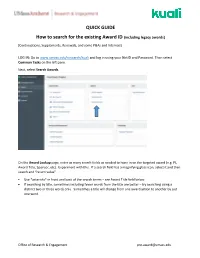

QUICK GUIDE How to Search for the Existing Award ID (Including Legacy

QUICK GUIDE How to search for the existing Award ID (including legacy awards) (Continuations, Supplements, Renewals, and some P&As and Internals) LOG IN: Go to www.umass.edu/research/kuali and log in using your NetID and Password. Then select Common Tasks on the left pane. Next, select Search Awards. On the Award Lookup page, enter as many search fields as needed to hone in on the targeted award (e.g. PI, Award Title, Sponsor, etc). Experiment with this. If a search field has a magnifying glass icon, select it and then search and “return value”. • Use *asterisks* in front and back of the search terms – see Award Title field below. • If searching by title, sometimes including fewer words from the title are better – try searching using a distinct two or three words only. Sometimes a title will change from one award action to another by just one word. Office of Research & Engagement [email protected] • After searching, run a report by selecting spreadsheet (seen below this chart on the left). Suggestions: Save as an Excel Workbook when multiple award records appear in order to hone in on the correct version. Delete columns as needed and add a filter to help with the sort and search process. Office of Research & Engagement [email protected] Identify the correct award Always select the so-called “Parent” award – the suffix is always “-00001” Note: To confirm linkage with the correct legacy award record: • In Kuali, select Medusa in the “-00001” record. • In the list that appears, select any award record except for the “-00001” Parent (the legacy data does not reside in the “Parent” record). -

Trees, Intestines and William the Conqueror*

TREES, INTESTINES AND WILLIAM THE CONQUEROR* İSLAM KAVAS** Before modern times, a ruler needed more than election in order to get public approval. It was supposed to be proved that ruling was a certain destiny for the ruler by blood or divine approval. The Normans, especially after they conquered and began to rule England in 1066, needed legitimacy as well. Some Norman chronicles used dreams and prophecy, as did many other dynasties’ chronicles.1 The current study will focus on the dream of Herleva, mother of William the Conqueror, its content, and its meaning. The accounts of William of Malmesbury, Wace, and Benoît de Saint-Maure will be the sources for the dream. I will argue that the dream of Herleva itself and its content are not related randomly. They have a function and a meaning aff ected by historical background of Europe. According to the chronicle sources, Herleva or Arlette, was a daughter of a burgess2 and a pollincter, who prepared corpses for burial, named Fulbert.3 She was living at Falaise where William was born in 1027-1028.4 She immediately attrac- ted Robert, William’s father, as soon as they met. Robert took her to his bed. One of these occasions was special because Herleva had an exceptional dream. This dream was about their future son, William the Conqueror. The dream of Herleva is transmitted to us through three diff erent versions * This article is supported by The Scientifi c and Technological Research Council of Turkey. ** Dr., Eskişehir Osmangazi University, Faculty of Science and Letters, Department of History, Eskişehir/TURKEY, [email protected] 1 The writer works on a comperative history of founding dreams and this paper is a part of this work. -

What Is the Anglo-Norman Brut? During the 13Th and 14Th Centuries in England, a Number of Texts Were Written in the Insular Dial

What is the Anglo-Norman Brut?1 During the 13th and 14th centuries in England, a number of texts were written in the insular dialect of French, commonly referred to as Anglo-Norman or Anglo-French, which purported to recount the history of the kings of the island. These histories, known in the vernacular as Bruts both then and in our times2, after the eponymous founder of Britain, are defined by Diana Tyson in her list of Brut manuscripts as, “factual historical narratives, or genuine attempts thereat, of the era from the Heptarchy into the Plantagenet period, or a section thereof.”3 These manuscripts are a heterogeneous group, differing significantly in character and in content though in all cases their narrative is based, in varying degrees, upon the Historia regum Britanniae and claim to tell the history of the country from Brutus up to mostly contemporary times. A number of texts fall under the heading of ‘Anglo-Norman Brut’, in verse and in prose and the following survey will help clarify how these texts are interrelated. The history of the Anglo-Norman Brut begins with a lost text. Completed in 1139, Gaimar’s Estoire des Engleis4 is a history of the English kings, the earliest Anglo-Norman chronicle as well as the first French history of the Saxon kings, beginning with the arrival of the Saxons and ending in 1100. Written at a similar time as Geoffrey of Monmouth Historia, it is clear that Gaimar’s work as it is now known is incomplete. The opening lines of the work suggest that the extant text was once preceded by a history of the pre-Saxon times, including the reign of Arthur. -

Diptico Quiropractica Copia

VIII QUEEN Award Guidelines María CHIROPRACTIC Cristina Sponsored by the Banco Santander Award Call for Papers: VIII Queen María Cristina Award. The Real Centro Universitario Escorial-María Cristina invites authors from all nations to submit papers for this award sponsored by the Santander Bank. Category: CHIROPRACTIC AWARD GUIDELINES 1 In regard to the award, an author may submit one or more papers. The paper must be unpublished and authored by one or more people. This is an international award and the papers may be presented in English or Spanish. The research paper must be original, neither published in any journal nor presented to other award contests or conferences. 2 The research papers may be on Basic Sciences (experimental models, Anatomy, Physiology, Biomechanics, Immunology, etc), Clinical Sciences (Analytical and Diagnostic Methods, including intra- and inter-examiner reliability), Clinical Trials, Retrospective Cohort Studies, and areas of specific interest (Anthropology, Epidemiology, and Education) related to Chiropractic. 3 Papers need to be submitted using Times New Roman font in 12 pt with 1.5 line spacing, in a Word-format (.doc or .docx) to the email address [email protected] from an account that ought not to revel the identity of the author. On the first page, the category should be indicated (CHIROPRACTIC), title of the paper, and the pseudonym (pen name) of the author. The real name(s) of the author(s) may not appear on the front page or any page throughout the paper. If the real name is found in any part of the paper or the sending address displays the real identity of the sender, it will be considered disqualified for the award. -

Age of Chivalry

The Constraints Laws on Warfare in the Western World War Edited by Michael Howard, George J. Andreopoulos, and Mark R. Shulman Yale University Press New Haven and London Robert C . Stacey 3 The Age of Chivalry To those who lived during them, of course, the Middle Ages, as such, did not exist. If they lived in the middleof anything, most medieval people saw themselves as living between the Incarnation of God in Jesus and the end of time when He would come again; theirown age was thus a continuation of the era that began in the reign of Caesar Augustus with his decree that all the world should be taxed. The Age of Chivalry, however, some men of the time- mostly knights, the chevaliers, from whose name we derive the English word "chivalry"-would have recognized as an appropriate label for the years between roughly I 100 and 1500.Even the Age of Chivalry, however, began in Rome. In the chansons de geste and vernacular histories of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, Hector, Alexander, Scipio, and Julius Caesar appear as the quintessential exemplars of ideal knighthood, while the late fourth or mid-fifth century Roman military writer Vcgetius remained far and away the most important single authority on the strategy and tactics of battle, his book On Military Matters (De re military passing in transla- tion as The Book of Chivalry from the thirteenth century on. The Middle Ages, then, began with Rome; and so must we if we are to study the laws of war as these developed during the Age of Chivalry. -

A Knights Own Book of Chivalry: Geoffroi De Charny Free

FREE A KNIGHTS OWN BOOK OF CHIVALRY: GEOFFROI DE CHARNY PDF Geoffroi de Charny,Richard W. Kaeuper,Elspeth Kennedy | 128 pages | 12 May 2005 | University of Pennsylvania Press | 9780812219098 | English | Pennsylvania, United States Geoffroi de Charny - Wikipedia Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Richard W. Kaeuper Introduction. Elspeth Kennedy Translator. On the great influence of a valiant lord: "The companions, who see that good warriors are honored by the great lords for their prowess, become more determined to attain this level of prowess. Read how an aspiring knight of the fourteenth century would conduct himself and learn what he would have needed to know when traveling, fighting, appearing in court, and engaging fellow knights. This is the most authentic and complete manual on the day-to-day life of the knight that has survived the centuries, and this edition contains a specially commissioned introduction from historian Richard W. Kaeuper that gives the history of both the book and its author, who, among his other achievements, was the original owner of the Shroud of Turin. Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. More Details Original Title. Other Editions 3. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. Lists with This Book. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 4. Rating details. More filters. Sort order. -

MANY MOTIVES: GEOFFREY of MONMOUTH and the REASONS for HIS FALSIFICATION of HISTORY John J. Berthold History 489 April 23, 2012

MANY MOTIVES: GEOFFREY OF MONMOUTH AND THE REASONS FOR HIS FALSIFICATION OF HISTORY John J. Berthold History 489 April 23, 2012 i ABSTRACT This paper examines The History of the Kings of Britain by Geoffrey of Monmouth, with the aim of understanding his motivations for writing a false history and presenting it as genuine. It includes a brief overview of the political context of the book at the time during which it was first introduced to the public, in order to help readers unfamiliar with the era to understand how the book fit into the world of twelfth century England, and why it had the impact that it did. Following that is a brief summary of the book itself, and finally a summary of the secondary literature as it pertains to Geoffrey’s motivations. It concludes with the claim that all proposed motives are plausible, and may all have been true at various points in Geoffrey’s career, as the changing times may have forced him to promote the book for different reasons, and under different circumstances than he may have originally intended. Copyright for this work is owned by the author. This digital version is published by McIntyre Library, University of Wisconsin Eau Claire with the consent of the author. ii CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 Who was Geoffrey of Monmouth? 3 Historical Context 4 The Book 6 Motivations 11 CONCLUSION 18 WORKS CITED 20 WORKS CONSULTED 22 1 Introduction Sometime between late 1135 and early 1139 Geoffrey of Monmouth released his greatest work, Historia Regum Britanniae (History of the Kings of Britain in modern English). -

Cornwall in the Early Arthurian Tradition It Is Believed That an Actual “King Arthur” Lived in 6Th Century AD in the Southwe

Cornwall in the Early Arthurian Tradition Heather Dale April 2008 It is believed that an actual “King Arthur” lived in 6th Century AD in the southwestern area of Britain. A brief history lesson is needed to provide the backdrop to this historical Arthur. In 43 AD, the Romans occupied Britain, subduing the northern Pictish & Scottish tribes, and incorporating the pre-literate but somewhat more civilized Celtic peoples into the Roman Empire. The Romans intermarried with the Celts, who emulated their customs and superior technology; these Romanized Celts became known as Britons. When the Romans abandoned Britain in 410 AD, the Britons found themselves attacked on all sides: the northern tribes pushed south, the Irish raided from the west, and fierce Germanic tribes (Angles, Saxons, Jutes, Franks, Frisians) and Norsemen slowly pushed the Celts into southwestern Wales and Cornwall. Some even fled across to the Continent, establishing Brittany in western France and becoming known as Bretons. It is in this turbulent post-Roman time that a brave man, perhaps a sort of tribal chieftain, led a small force of Britons into battle with the Germanic tribes. And due to tactical skill, superior fighting prowess and/or incredible luck (we will never know) this Artorius or Arthur held back the Germanic hordes from his corner of Britain for 30 years, a full generation. This incredible feat is first mentioned in a 6th century quasi-historical Latin chronicle by the monk Gildas. Later chroniclers added detail of dubious historical accuracy but great heroism to the tale of Arthur. The Venerable Bede wrote in 731 AD about the first great victory over the Saxons at Mount Badon (surmised by some to be Liddington Castle near Swindon), and the Welsh chronicler Nennius bases his 9th century story on material from the rich Welsh storytelling tradition.