The Design, Management and Operation of Flexible Transport

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Future of LAMAT System in Asian Developing Countries: Whether to Eliminate Or Tolerate It? (アジア諸国における LAMAT システムに関する研究) Veng Kheang PHUN 研究員

16:00~16:35 The Future of LAMAT System in Asian Developing Countries: Whether to Eliminate or Tolerate It? (アジア諸国における LAMAT システムに関する研究) Veng Kheang PHUN 研究員 1.Introduction The term “LAMAT” refers to the indigenous 3.Results public transport modes that are Locally Adapted, Results from modal share showed that Bicycle Modified and Advanced for a certain transport taxi, Man-pulled rickshaw and Animal cart have service in a particular city or region. LAMAT been almost disappeared from 11 Asian developing includes all intermediate transport modes between cities. Cycle rickshaws still exist in some cities private vehicles and conventional mass transit, including Dhaka and Cebu, but they have been ranging from non-motorized two-wheelers (bicycle banned from entering the CBDs. Motorized taxi) up to motorized four wheelers (minibus), with LAMAT modes remain active in urban streets, a maximum seating capacity of about 25 passengers. while some cities regulated and prohibited their LAMAT has been proposed and used instead of the operations. Fixed-route LAMAT like microbus and previous term “Paratransit” due to its numerous minibus had high modal share in Jakarta, descriptions found in Asian countries. Ulaanbaatar and Manila. In Phnom Penh, SEM LAMAT plays a significant role in Asian results showed that drivers of Motodops supported developing cities. It provides not only personalized for the public bus service and intended to operate as and flexible transport services to citizens with its feeder mode, but drivers of Remorks did not. A certain service quality and reasonable fare but also more effective regulation (e.g., standard fare, assists the social activities through its service uniform) also showed to encourage the feeder availability and job opportunities for the poor or service of the public bus. -

Transport in India Transport in the Republic of India Is an Important

Transport in India Transport in the Republic of India is an important part of the nation's economy. Since theeconomic liberalisation of the 1990s, development of infrastructure within the country has progressed at a rapid pace, and today there is a wide variety of modes of transport by land, water and air. However, the relatively low GDP of India has meant that access to these modes of transport has not been uniform. Motor vehicle penetration is low with only 13 million cars on thenation's roads.[1] In addition, only around 10% of Indian households own a motorcycle.[2] At the same time, the Automobile industry in India is rapidly growing with an annual production of over 2.6 million vehicles[3] and vehicle volume is expected to rise greatly in the future.[4] In the interim however, public transport still remains the primary mode of transport for most of the population, and India's public transport systems are among the most heavily utilised in the world.[5] India's rail network is the longest and fourth most heavily used system in the world transporting over 6 billionpassengers and over 350 million tons of freight annually.[5][6] Despite ongoing improvements in the sector, several aspects of the transport sector are still riddled with problems due to outdated infrastructure, lack of investment, corruption and a burgeoning population. The demand for transport infrastructure and services has been rising by around 10% a year[5] with the current infrastructure being unable to meet these growing demands. According to recent estimates by Goldman Sachs, India will need to spend $1.7 Trillion USD on infrastructure projects over the next decade to boost economic growth of which $500 Billion USD is budgeted to be spent during the eleventh Five-year plan. -

PDF Download Lonely Planet India

LONELY PLANET INDIA PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Lonely Planet,Sarina Singh,Michael Benanav,Abigail Blasi,Paul Clammer,Mark Elliott,Paul Harding,Anirban Mahapatra,John Noble,Kevin Raub | 1248 pages | 30 Oct 2015 | Lonely Planet Publications Ltd | 9781743216767 | English | Hawthorn, Victoria, Australia Lonely Planet India PDF Book Comprehensive travel insurance to cover theft, loss and medical problems as well as air evacuation is strongly recommended. Browse by continent Asia. Industry newcomer Jio the first mobile network to run entirely on 4G data technology; www. Javascript is not enabled in your browser. With its sumptuous mix of traditions, spiritual beliefs, festivals, architecture and landscapes, your memories of India will blaze bright long after you've left its shores. New Releases. German: Delhi , Kolkata , Mumbai , Chennai. If it feels wrong, trust your instincts. Flash photography may be prohibited in certain areas of a shrine or historical monument, or may not be permitted at all. Roaming connections are excellent in urban areas, poor in the countryside and the Himalaya. Lonely Planet is your passport to India, with amazing travel experiences and the best planning advice. Reputable organisations will insist on safety checks for adults working with children. Don't expect to find these items readily available. Many people deal with an on-the-spot fine by just paying it, to avoid trumped-up charges. The Travel Kitchen: Chennai Chicken Best of Ireland travel guide - 3rd edition Guidebook. The standard of toilet facilities varies enormously across the country. As well as international organisations, local charities and NGOs often have opportunities, though it can be harder to assess the work that these organisations are doing. -

Rickshaw Art in Bangladesh

76 MIMAR 39 RICKSHAW ART IN BANGLADESH New buildings in Dhaka sometimes find their way onto the back of a rickshaw before the front of a postcard. Tom Learmonth describes the plethora of images that constitute Dhaka's traffic art. he cycle rickshaw is the pre dominant means of transport T in Bangladesh. It provides personal transport at a price determined not by the enormous cost of imported oil but by the barely subsistence level of wages of the landless poor. It thus makes use of Bangladesh's most abundant resource, her people. Two thirds of Dhaka's traffic is made up of an estimated 150,000 rickshaws. There are thought to be around a million in the country despite periodic attempts to limit them by governments embarrassed by what they see as a sign of backwardness. The quality of life for the drivers - still known as rickshaw pullers although the hand pulled version has now disappeared - is poor. Few live beyond 40, yet their earnings are far higher than the agricultural wages they left behind in the villages. Often they are supporting families left behind. In Dhaka they are relatively well-off in the hierarchy of the urban poor. The machines they struggle to pedal, with two passengers or a heavy goods load aboard, evolved from the hand pulled rickshaw design coupled to the 1900s English policeman's bicycle, which is still manufactured by the million in India and China. The rickshaws are A main thoroughfare in Old Dhaka the rickshaw. They are paid by the assembled piece by piece in specialized showing a typical ratio oj rickshaws to rickshaw owners, almost entirely middle workshops in the cities. -

Probike/Prowalk Florida City Comes up with the Right Answers Florida Bike Summit Brought Advocacy to Lawmakers' Door

Vol. 13, No. 2 Spring 2010 OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER OF THE FLORIDA BICYCLE ASSOCIATION, INC. Reviewing the April 8 event. Florida Bike Summit brought Lakeland: ProBike/ProWalk advocacy to lawmakers’ doorstep Florida city comes up with the right answers by Laura Hallam, FBA Executive Director photos: by Herb Hiller Yes, yes, yes and no. Woman’s Club, Lakeland Chamber of Keri Keri Caffrey Four answers to four questions you may be Commerce, fine houses and historical mark- asking: ers that celebrate the good sense of people 1. Shall I attend ProBike/ProWalk Florida who, starting 125 years ago, settled this rail- in May? road town. 2. Shall I come early and/or stay in I might add about those people who settled Lakeland after the conference? Lakeland that they also had the good fortune 3. Is Lakeland not only the most beautiful of having Publix headquarter its enterprise mid-sized city in Florida but also, rare here, so that subsequent generations of among cities of any size, year by year get- Jenkins folk could endow gardens, children’s ting better? play areas and everything else that makes photos: Courtesy of Central Visitor Florida & Bureau Convention Above: Kathryn Moore, Executive Director embers of FBA from of the So. Fla. Bike Coalition (right), works around the state gath- the FBA booth. Below: Representative ered with Bike Florida Adam Fetterman takes the podium. at the Capitol for the 2nd annual Florida Bike Summit. Modeled after the high- ly successful National PAID Bike Summit that recently NONPROFIT U.S. POSTAGE POSTAGE U.S. PERMIT No. -

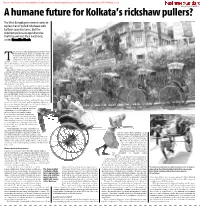

A Humane Future for Kolkata's Rickshaw Pullers?

A humane future for Kolkata’s rickshaw pullers? The West Bengal government wants to PHOTOS: SUBRATA MAJUMDER replace hand-pulled rickshaws with battery-operated ones. But the rickshaw pullers are apprehensive that they will lose their livelihood, writes Kamalika Ghosh he presence of the hand-pulled rickshaw even today in Kolkata perhaps encapsulates the exis- tential crisis that defines the city. It is a metrop- olis that still perpetuates its colonial legacy in its distinctive architecture, struggles to keep pace Twith the rest of the country and is marked by disruption and chaos. The rickshaw, therefore, is symbolic of the city striv- ing to come to terms with the pressing concerns of a mod- ern society. Efforts have been on to give the metro’s streets a more contemporary visual appeal since 2005. It was in that year that the erstwhile Left Front government decided to ban hand-pulled rickshaws, declaring the system to be a travesty of human dignity. Amid protests, the government paved the way for the death of the hand-pulled rickshaw by tabling the Calcutta Hackney-Carriage (Amendment) Bill, 2006 in the state legislative assembly. However, what the then government had not thought necessary to ponder on while trying to usher in change was the need to provide an alternative source of livelihood to the impoverished rickshaw pullers. The Bill was challenged and the Calcutta High Court decreed a stay on the legislation. However, the Kolkata Municipality hasn’t issued any fresh licences since 2005. The current government has modified the ban: it has decided to replace the hand-pulled rickshaws with some- thing more modern that would not tell on the dignity of the rickshaw puller. -

Changing Modes of Transportation: a Case Study of Rajshahi City Corporation

Changing Modes of Transportation: A Case Study of Rajshahi City Corporation Rabeya Basri Lecturer Department of Economics University of Rajshahi, 6205 Tahmina Khatun Lecturer Department of Humanities (Economics) Rajshahi University of Engineering and Technology Rajshahi Md. Selim Reza Assistant Professor Department of Economics University of Rajshahi, 6205 And Dr. M. Moazzem Hossain Khan Professor Department of Economics University of Rajshahi, 6205 Abstract This study carried out about the comparative study of the changing mode of transportation. Battery operated auto-rickshaws are newly introduced vehicle in city areas and took the place of rickshaw because of cheap cost and comfort. We selected Rajshahi City Corporation (RCC) as a sample area, because there are huge rickshaws and auto-rickshaws used for daily travelling. This study based on primary data and tried to show the socio-economic conditions which ultimately influence the income of auto-rickshaw drivers and rickshaw pullers. Here, linear regression model is used to estimate the income determinants and in case of auto- rickshaw opportunity cost, family member, and other cost have significant impact on income where ownership, age, education of auto-rickshaw drivers have insignificant impact. While in the case of rickshaw other cost and family member have positive and significant effect on income. But education, ownership of vehicle and opportunity cost have found insignificant here. To increase the income of auto drivers as well as rickshaw pullers, number of rickshaw and auto-rickshaw must be limited in city area and ensure that the vehicles have licence issued by proper authority. I. Introduction Economic development and transportation are closely related. -

Faqs on Rickshaws, Moto-Taxis and Tuk-Tuks

FAQs on Rickshaws, Moto-taxis and Tuk-tuks Types of Rickshaws, Tuk-tuks or Definition Moto-taxis Pulled rickshaw A type of human-powered transport where a person pulls a two-wheeled cart which seats up to two people. Cycle rickshaw or A type of human-powered transport where a person pedicab on a bicycle pulls a two-wheeled cart which seats up to two people. Auto rickshaw, tuk-tuk or A motorised version of the original pulled and cycle moto-taxi rickshaws commonly used as vehicles for hire. Electric rickshaw, e-rickshaw or A three-wheeled vehicle pulled by an electric motor 650- e-tuk-tuk 1400 w What are the laws on using rickshaws and tuk-tuks inIreland? • If a rickshaw or tuk-tuk is fitted with a small engine or electric motor of any kind including e-bike it is essentially considered to be a mechanically propelled vehicle (MPV) • Under road traffic law if an MPV is used in a public place it is subject to all of the regulatory controls that apply to other vehicles i.e. it must be roadworthy, registered, taxed and comply with all regulations mentioned below. • The driver must have appropriate driving licence and insurance to drive that vehicle. What laws apply to MPVs? Regulations* applying to MPVs are: • S.I. No.5 of 2003 - Road Traffic Construction and Use of Vehicles Regulations • S.I. No. 190 of 1963 - Road Traffic Construction, Equipment and Use of Vehicles Regulations • S.I. No. 189 of 1963 - Road Traffic Lighting of Vehicles *The above regulations are in original format and amendments can be viewed on irishstatutebook.ie What is -

Landscape of Motion Localization Process of Mechanized Vehicles in Indian Cities

62 quarterly, Vol.2, No.6 | Winter 2015 Fig.11. painting of rickshaw as urban art. Source: http://kishnakathad.blogspot.com Reference list •Choudhury, I. (2009). Proceedings of the International Conference Engilish by Abolfazl M. Tehran: Center for Urban Development and on Nature in Eastern Art. Translated from Engilish by Parvin M. Architecture research, 2010. Tehran: Art academy of Islamic Repoblic of Iran, 2009. • Linch, K. (1995). Image of city. Translated from Engilish by • Edensor, T. (1998). The Culture of the Indian Street. In Fyfe, N. R. Manouchehr M. Tehran: University of Tehran, 2010. (Ed.), Images of the Street –Planning, Identity and Control in Public • Linch. K. (2002). The theory of the City form. Translated from Space. London/New York: Routledge. (205-221). Engilish by Hossein B. Tehran: University of Tehran, 2008. • Ghosal, A. & Atluri, V. P. (2011). Architectural Study of Hybrid • Mansouri. S. A. (2010). Identity of urban landscape: the historical Electric Propulsion Systems for Indian Cities. 13th World Congress study of the evolution of the urban landscape in Iran. Manzar in Mechanism and Machine Science, Guanajuato, México. magazine (9): 30-33. • Girot, Ch. (2006). Vision in Motion: Representing Landscape • Mort, N. (2008). Micro Trucks: Tiny Utility Vehicles from Around in Time, the Landscape Urbanism Reader New York: Princeton the World. London: Veloce Publishing Ltd. Architectural Press. (87- 104). • Nasr. S. H. (2000). Man and Nature: The Spiritual Crisis of Modern • Hasan, T. & Hasan K, J. (2012). Socio-Economic Profile of Cycle Humanity. Translated from Engilish by Abdolrahim G. Tehran: Rickshaw Pullers: A Case Study. European Scientific Journal, 8 (1): Islamic Culture Publishing Office, 2008. -

Weather: a Force of Nature 33

WEATHER: A FORCE OF NATURE 33 Whirling devil Hadi Dehghanpour This photograph captures the moment a powerful dust devil hits a group of tents in a village near Noush Abad in Iran. Dust devils are relatively small, short-lived whirlwinds occurring during sunny conditions when the air in contact with the ground is heated strongly. This heating creates shallow convection currents that tend to organize into small regions, or cells, of ascending and descending air near ground level. Areas of weak rotation, associated with local variations in the wind speed and direction, can be strongly focussed and amplified as air converges in towards the areas of ascending air. This process occasionally results in the development of a well-defined column of strongly rotating air, and a dust devil is born. Although most dust devils are harmless, they occasionally grow large and strong enough to constitute a hazard to outdoor activities, as in this example. Dust devils resemble tornadoes, in so much as they are a strongly rotating column of air. However, they are almost always weaker than tornadoes and tend to be much shallower. Crucially, whilst the rotation in dust devils generally only extends a few tens of metres to perhaps 100–200 m (328–656 ft) above ground level, tornadoes are connected to the base of a convective cloud aloft. Canon 5D Mark III + Canon 75–300 mm: 1/400 s; f/11; 120 mm; ISO-100. Beating in vain Tohid Mahdizadeh Bush and forest fires, such as this heathland fire in northwest Iran, can be a major hazard in arid and semi-arid regions of the world. -

Towards a Novel Regime Change Framework: Studying Mobility Transitions in Public Transport Regimes in an Indian Megacity

Towards a novel regime change framework: studying mobility transitions in public transport regimes in an Indian megacity Article (Accepted Version) Ghosh, Bipashyee and Schot, Johan (2019) Towards a novel regime change framework: studying mobility transitions in public transport regimes in an Indian megacity. Energy Research & Social Science, 51. pp. 82-95. ISSN 2214-6296 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/81338/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk Towards a novel regime change framework: Studying mobility transitions in public transport regimes in an Indian megacity Bipashyee Ghosha , Johan Schotb a Science Policy Research Unit, University of Sussex, Jubilee Building, Falmer, Brighton, BN1 9SL, UK b Utrecht Centre for Global Challenges (UGLOBE), Utrecht University, The Netherlands Abstract Mobility systems in megacities are facing persistent sustainability problems. -

INDIAN INSTITUTE of TECHNOLOGY GUWAHATI Guwahati-781039 November 2007

DESIGN DEVELOPMENT OF AN INDIGENOUS TRICYCLE RICKSHAW Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Amarendra Kumar Das Department of Design INDIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY GUWAHATI Guwahati-781039 November 2007 0 DESIGN DEVELOPMENT OF AN INDIGENOUS TRICYCLE RICKSHAW Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Amarendra Kumar Das 994802 Under supervision of Debkumar Chakrabarti, Ph D Department of Design INDIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY GUWAHATI Guwahati-781039 November 2007 TH-0529_994802 1 Certificate 30 th November 2007 The research work presented in this thesis entitled ‘Design Development of an Indigenous Tricycle Rickshaw’ has been carried out under my supervision and is a bonafide work of Mr. Amarendra Kumar Das. This work submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy is original and has not been submitted for any other degree or diploma to this institute or to any other institute or university. He has also fulfilled all the requirements including mandatory coursework as per the rules and regulations for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati. Debkumar Chakrabarti, PhD Associate Professor, Department of Design Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati Guwahati 781 039 Asom, India TH-0529_994802 2 Acknowledgement I express my sincere gratitude to all those people who helped me during the present research work and acknowledge the support received from various institutions, therefore I dedicate my works to all of them. Although it is impossible to name all people and institutions involved in this endeavor without missing some of them inadvertently, I would like to mention a few specifically.