Regulation of Endothelial Gene Transcription By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nitroxide-Mediated Polymerization

Chapter 7 Nitroxide-Mediated Polymerization 7.1 Introduction Controlled radical polymerization (CRP) under radical initiation conditions belongs to priority areas in the development of the synthetic chemistry of polymers of the last years [1–16]. Nitroxide-mediated polymerization (NMP) was invented by Solomon [1, 13]. Since this discovery, nitroxide-mediated radical polymerization is a power- ful method to synthesize well-defined macromolecular architectures with precisely controlled topologies, compositions, microstructures, and functionalities [3–5]. The most common mechanisms for reversible activation in polymerization reactions are schematically illustrated in Scheme 7.1. Persistent radical effect (PRE) occurs when two radicals are generated at the same time, at the same rate, and one is more persistent than the other, the self-termination reactions are lowered, leading to an unusually high selectivity for the cross-coupling reaction [10]. The effect has been investigated for the preparation of macromolecules with a narrow molar mass distribution through radical polymerization. Nitroxide-mediated polymerization is widely applied in industrial polymer syn- theses as a method for production of large-tonnage polymers and is employed to manufacture new pigments, sealants, emulsion stabilizers, and block copolymers, etc., with a various set of properties. NMP has also paved an avenue for complex macromolecular architectures (statistical, block, graft) in the fields of nanoscience and nanotechnology [5, 9, 12] and references cited therein. A brief summary of NMP developments in both the patent and open literature during the period of the early Scheme 7.1 Mechanisms for reversible activation in polymerization reactions [6] © Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2020 161 G. I. Likhtenshtein, Nitroxides, Springer Series in Materials Science 292, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-34822-9_7 162 7 Nitroxide-Mediated Polymerization 1980–2000 was presented in [11]. -

ASPH-Notch Axis Guided Exosomal Delivery of Prometastatic Secretome

Lin et al. Molecular Cancer (2019) 18:156 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-019-1077-0 RESEARCH Open Access ASPH-notch Axis guided Exosomal delivery of Prometastatic Secretome renders breast Cancer multi-organ metastasis Qiushi Lin1†, Xuesong Chen2†, Fanzheng Meng3†, Kosuke Ogawa4†, Min Li5, Ruipeng Song3, Shugeng Zhang3, Ziran Zhang3, Xianglu Kong3, Qinggang Xu1,6, Fuliang He1,7, Xuewei Bai8, Bei Sun8, Mien-Chie Hung9,10, Lianxin Liu3,11*, Jack Wands4* and Xiaoqun Dong12,1* Abstract Background: Aspartate β-hydroxylase (ASPH) is silent in normal adult tissues only to re-emerge during oncogenesis where its function is required for generation and maintenance of malignant phenotypes. Exosomes enable prooncogenic secretome delivering and trafficking for long-distance cell-to-cell communication. This study aims to explore molecular mechanisms underlying how ASPH network regulates designated exosomes to program development and progression of breast cancer. Methods: Stable cell lines overexpressing or knocking-out of ASPH were established using lentivirus transfection or CRISPR-CAS9 systems. Western blot, MTT, immunofluorescence, luciferase reporter, co-immunoprecipitation, 2D/3-D invasion, tube formation, mammosphere formation, immunohistochemistry and newly developed in vitro metastasis were applied. Results: Through physical interactions with Notch receptors, ligands (JAGs) and regulators (ADAM10/17), ASPH activates Notch cascade to provide raw materials (especially MMPs/ADAMs) for synthesis/release of pro-metastatic exosomes. Exosomes orchestrate EMT, 2-D/3-D invasion, stemness, angiogenesis, and premetastatic niche formation. Small molecule inhibitors (SMIs) of ASPH’s β-hydroxylase specifically/efficiently abrogated in vitro metastasis, which mimics basement membrane invasion at primary site, intravasation/extravasation (transendothelial migration), and colonization/outgrowth at distant sites. -

Mutant IDH, (R)-2-Hydroxyglutarate, and Cancer

Downloaded from genesdev.cshlp.org on October 1, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press REVIEW What a difference a hydroxyl makes: mutant IDH, (R)-2-hydroxyglutarate, and cancer Julie-Aurore Losman1 and William G. Kaelin Jr.1,2,3 1Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts 02215, USA; 2Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Chevy Chase, Maryland 20815, USA Mutations in metabolic enzymes, including isocitrate whether altered cellular metabolism is a cause of cancer dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) and IDH2, in cancer strongly or merely an adaptive response of cancer cells in the face implicate altered metabolism in tumorigenesis. IDH1 of accelerated cell proliferation is still a topic of some and IDH2 catalyze the interconversion of isocitrate and debate. 2-oxoglutarate (2OG). 2OG is a TCA cycle intermediate The recent identification of cancer-associated muta- and an essential cofactor for many enzymes, including tions in three metabolic enzymes suggests that altered JmjC domain-containing histone demethylases, TET cellular metabolism can indeed be a cause of some 5-methylcytosine hydroxylases, and EglN prolyl-4-hydrox- cancers (Pollard et al. 2003; King et al. 2006; Raimundo ylases. Cancer-associated IDH mutations alter the enzymes et al. 2011). Two of these enzymes, fumarate hydratase such that they reduce 2OG to the structurally similar (FH) and succinate dehydrogenase (SDH), are bone fide metabolite (R)-2-hydroxyglutarate [(R)-2HG]. Here we tumor suppressors, and loss-of-function mutations in FH review what is known about the molecular mechanisms and SDH have been identified in various cancers, in- of transformation by mutant IDH and discuss their im- cluding renal cell carcinomas and paragangliomas. -

Environmental Influences on Endothelial Gene Expression

ENDOTHELIAL CELL GENE EXPRESSION John Matthew Jeff Herbert Supervisors: Prof. Roy Bicknell and Dr. Victoria Heath PhD thesis University of Birmingham August 2012 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT Tumour angiogenesis is a vital process in the pathology of tumour development and metastasis. Targeting markers of tumour endothelium provide a means of targeted destruction of a tumours oxygen and nutrient supply via destruction of tumour vasculature, which in turn ultimately leads to beneficial consequences to patients. Although current anti -angiogenic and vascular targeting strategies help patients, more potently in combination with chemo therapy, there is still a need for more tumour endothelial marker discoveries as current treatments have cardiovascular and other side effects. For the first time, the analyses of in-vivo biotinylation of an embryonic system is performed to obtain putative vascular targets. Also for the first time, deep sequencing is applied to freshly isolated tumour and normal endothelial cells from lung, colon and bladder tissues for the identification of pan-vascular-targets. Integration of the proteomic, deep sequencing, public cDNA libraries and microarrays, delivers 5,892 putative vascular targets to the science community. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Expression Signatures of the Lipid-Based Akt Inhibitors Phosphatidylinositol Ether Lipid Analogues in NSCLC Cells

Published OnlineFirst May 6, 2011; DOI: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-1028 Molecular Cancer Therapeutic Discovery Therapeutics Expression Signatures of the Lipid-Based Akt Inhibitors Phosphatidylinositol Ether Lipid Analogues in NSCLC Cells Chunyu Zhang1, Abdel G. Elkahloun2, Hongling Liao3, Shannon Delaney1, Barbara Saber1, Betsy Morrow1, George C. Prendergast4, M. Christine Hollander1, Joell J. Gills1, and Phillip A. Dennis1 Abstract Activation of the serine/threonine kinase Akt contributes to the formation, maintenance, and therapeutic resistance of cancer, which is driving development of compounds that inhibit Akt. Phosphatidylinositol ether lipid analogues (PIA) are analogues of the products of phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K) that inhibit Akt activation, translocation, and the proliferation of a broad spectrum of cancer cell types. To gain insight into the mechanism of PIAs, time-dependent transcriptional profiling of five active PIAs and the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (LY) was conducted in non–small cell lung carcinoma cells using high-density oligonucleotide arrays. Gene ontology analysis revealed that genes involved in apoptosis, wounding response, and angiogen- esis were upregulated by PIAs, whereas genes involved in DNA replication, repair, and mitosis were suppressed. Genes that exhibited early differential expression were partitioned into three groups; those induced by PIAs only (DUSP1, KLF6, CENTD2, BHLHB2, and PREX1), those commonly induced by PIAs and LY (TRIB1, KLF2, RHOB, and CDKN1A), and those commonly suppressed by PIAs and LY (IGFBP3, PCNA, PRIM1, MCM3, and HSPA1B). Increased expression of the tumor suppressors RHOB (RhoB), KLF6 (COPEB), and CDKN1A (p21Cip1/Waf1) was validated as an Akt-independent effect that contributed to PIA-induced cytotoxicity. Despite some overlap with LY, active PIAs have a distinct expression signature that contributes to their enhanced cytotoxicity. -

Comprehensive Array CGH of Normal Karyotype Myelodysplastic

Leukemia (2011) 25, 387–399 & 2011 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0887-6924/11 www.nature.com/leu LEADING ARTICLE Comprehensive array CGH of normal karyotype myelodysplastic syndromes reveals hidden recurrent and individual genomic copy number alterations with prognostic relevance A Thiel1, M Beier1, D Ingenhag1, K Servan1, M Hein1, V Moeller1, B Betz1, B Hildebrandt1, C Evers1,3, U Germing2 and B Royer-Pokora1 1Institute of Human Genetics and Anthropology, Medical Faculty, Heinrich Heine University, Duesseldorf, Germany and 2Department of Hematology, Oncology and Clinical Immunology, Heinrich Heine University, Duesseldorf, Germany About 40% of patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDSs) 40–50% of MDS cases have a normal karyotype. MDS patients present with a normal karyotype, and they are facing different with a normal karyotype and low-risk clinical parameters are courses of disease. To advance the biological understanding often assigned into the IPSS low and intermediate-1 risk groups. and to find molecular prognostic markers, we performed a high- resolution oligonucleotide array study of 107 MDS patients In the absence of genetic or biological markers, prognostic (French American British) with a normal karyotype and clinical stratification of these patients is difficult. To better prognosticate follow-up through the Duesseldorf MDS registry. Recurrent these patients, new parameters to identify patients at higher risk hidden deletions overlapping with known cytogenetic aberra- are urgently needed. With the more recently introduced modern tions or sites of known tumor-associated genes were identi- technologies of whole-genome-wide surveys of genetic aberra- fied in 4q24 (TET2, 2x), 5q31.2 (2x), 7q22.1 (3x) and 21q22.12 tions, it is hoped that more insights into the biology of disease (RUNX1, 2x). -

Ribonucleotide Reductase Subunit M2B Deficiency Leads To

Am J Transl Res 2018;10(11):3635-3649 www.ajtr.org /ISSN:1943-8141/AJTR0084684 Original Article Ribonucleotide reductase subunit M2B deficiency leads to mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening and is associated with aggressive clinicopathologic manifestations of breast cancer Lijun Xue1*, Xiyong Liu2,6*, Qinchuan Wang3,4, Charlie Q Liu3, Yunru Chen3, Wei Jia5, Ronhong Hsie6, Yifan Chen8, Frank Luh2,6, Shu Zheng7, Yun Yen2,6,8 1Department of Pathology, Loma Linda University Medical Center, Loma Linda, CA 92354, USA; 2Sino-American Cancer Foundation, California Cancer Institute, Temple, CA 91780, USA; 3Department of Molecular Pharmacology, Beckman Research Institute, City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center, Duarte, CA 91010, USA; 4Surgical Oncology, Sir Runrun Shaw Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China; 5Cancer Epidemiology Program, University of Hawaii Cancer Center, Honolulu, HI 96813, USA; 6TMU Research Center of Cancer Translational Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan, ROC; 7Cancer Institute, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310009, Zhejiang, China; 8PhD Program of Cancer Biology and Drug Discovery, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan, ROC. *Co-first authors. Received August 27, 2018; Accepted October 19, 2018; Epub November 15, 2018; Published November 30, 2018 Abstract: Ribonucleotide reductase small subunit M2B (RRM2B) plays an essential role in maintaining mitochon- drial homeostasis. Mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP) is a key regulator of mitochondrial homeo- stasis. MPTP contributes to cell death and is crucial in cancer progression. RRM2B’s relation to MPTP is not well known, and the role of RRM2B in cancer progression is controversial. Here, our aim was to study the role of RRM2B in regulating MPTP and the association between RRM2B and clinicopathological manifestations in breast cancer. -

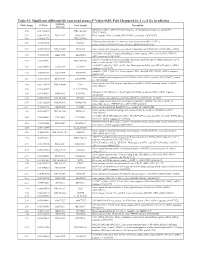

(P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 Vs. 0 Gy Irradiation

Table S1: Significant differentially expressed genes (P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 vs. 0 Gy irradiation Genbank Fold Change P -Value Gene Symbol Description Accession Q9F8M7_CARHY (Q9F8M7) DTDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratase (Fragment), partial (9%) 6.70 0.017399678 THC2699065 [THC2719287] 5.53 0.003379195 BC013657 BC013657 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:4152983, partial cds. [BC013657] 5.10 0.024641735 THC2750781 Ciliary dynein heavy chain 5 (Axonemal beta dynein heavy chain 5) (HL1). 4.07 0.04353262 DNAH5 [Source:Uniprot/SWISSPROT;Acc:Q8TE73] [ENST00000382416] 3.81 0.002855909 NM_145263 SPATA18 Homo sapiens spermatogenesis associated 18 homolog (rat) (SPATA18), mRNA [NM_145263] AA418814 zw01a02.s1 Soares_NhHMPu_S1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:767978 3', 3.69 0.03203913 AA418814 AA418814 mRNA sequence [AA418814] AL356953 leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor 6 {Homo sapiens} (exp=0; 3.63 0.0277936 THC2705989 wgp=1; cg=0), partial (4%) [THC2752981] AA484677 ne64a07.s1 NCI_CGAP_Alv1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:909012, mRNA 3.63 0.027098073 AA484677 AA484677 sequence [AA484677] oe06h09.s1 NCI_CGAP_Ov2 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:1385153, mRNA sequence 3.48 0.04468495 AA837799 AA837799 [AA837799] Homo sapiens hypothetical protein LOC340109, mRNA (cDNA clone IMAGE:5578073), partial 3.27 0.031178378 BC039509 LOC643401 cds. [BC039509] Homo sapiens Fas (TNF receptor superfamily, member 6) (FAS), transcript variant 1, mRNA 3.24 0.022156298 NM_000043 FAS [NM_000043] 3.20 0.021043295 A_32_P125056 BF803942 CM2-CI0135-021100-477-g08 CI0135 Homo sapiens cDNA, mRNA sequence 3.04 0.043389246 BF803942 BF803942 [BF803942] 3.03 0.002430239 NM_015920 RPS27L Homo sapiens ribosomal protein S27-like (RPS27L), mRNA [NM_015920] Homo sapiens tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 10c, decoy without an 2.98 0.021202829 NM_003841 TNFRSF10C intracellular domain (TNFRSF10C), mRNA [NM_003841] 2.97 0.03243901 AB002384 C6orf32 Homo sapiens mRNA for KIAA0386 gene, partial cds. -

Detecting Remote, Functional Conserved Domains in Entire Genomes by Combining Relaxed Sequence-Database Searches with Fold Recognition

HMMerThread: Detecting Remote, Functional Conserved Domains in Entire Genomes by Combining Relaxed Sequence-Database Searches with Fold Recognition Charles Richard Bradshaw1¤a, Vineeth Surendranath1, Robert Henschel2,3, Matthias Stefan Mueller2, Bianca Hermine Habermann1,4*¤b 1 Bioinformatics Laboratory, Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics, Dresden, Saxony, Germany, 2 Center for Information Services and High Performance Computing (ZIH), Technical University, Dresden, Saxony, Germany, 3 High Performance Applications, Pervasive Technology Institute, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana, United States of America, 4 Bioinformatics Laboratory, Scionics c/o Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics, Dresden, Saxony, Germany Abstract Conserved domains in proteins are one of the major sources of functional information for experimental design and genome-level annotation. Though search tools for conserved domain databases such as Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) are sensitive in detecting conserved domains in proteins when they share sufficient sequence similarity, they tend to miss more divergent family members, as they lack a reliable statistical framework for the detection of low sequence similarity. We have developed a greatly improved HMMerThread algorithm that can detect remotely conserved domains in highly divergent sequences. HMMerThread combines relaxed conserved domain searches with fold recognition to eliminate false positive, sequence-based identifications. With an accuracy of 90%, our software is able to automatically predict highly divergent members of conserved domain families with an associated 3-dimensional structure. We give additional confidence to our predictions by validation across species. We have run HMMerThread searches on eight proteomes including human and present a rich resource of remotely conserved domains, which adds significantly to the functional annotation of entire proteomes. -

Identification of Bleomycin and Radiation-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis Susceptibility Genes in Mice Anne-Marie Lemay Department Of

Identification of bleomycin and radiation-induced pulmonary fibrosis susceptibility genes in mice Anne-Marie Lemay Department of Human Genetics McGill University, Montréal February 4th, 2010 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Anne-Marie Lemay 2010 Comme il est profond, ce mystère de l’Invisible ! Nous ne pouvons le sonder avec nos sens misérables, avec nos yeux qui ne savent apercevoir ni le trop petit, ni le trop grand, ni le trop près, ni le trop loin, ni les habitants d’une étoile, ni les habitants d’une goutte d’eau… Guy de Maupassant Le Horla ii Table of contents Table of contents ................................................................................................... iii Abstract...................................................................................................................vi Résumé ................................................................................................................ viii Acknowledgments................................................................................................... x Abbreviations........................................................................................................ xii Original contributions to knowledge...................................................................xiv Author contribution to research...........................................................................xv List of figures ........................................................................................................ -

Study of Human Regulatory Mutations Associated with Pancreatic Diseases

Study of human regulatory mutations associated with pancreatic diseases by humanizing the zebrafish genome. Inês Maria Batista da Costa Mestrado em Biologia Celular e Molecular Departamento de Biologia da Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade do Porto (FCUP) Orientador José Bessa, PhD, Instituto de Investigação e Inovação em Saúde (i3S) Coorientador Chiara Perrod, PhD, Instituto de Investigação e Inovação em Saúde (i3S) 2018/19 This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant Todas as correções agreement No 680156 – ZPR). determinadas pelo júri, e só essas, foram efetuadas. O Presidente do Júri, Porto, ______/______/_________ Study of human regulatory mutations associated with pancreatic diseases by humanizing the zebrafish genome. Inês Maria Batista da Costa Mestrado em Biologia Celular e Molecular Departamento de Biologia da Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade do Porto (FCUP) Orientador José Bessa, PhD, Instituto de Investigação e Inovação em Saúde (i3S) Coorientador Chiara Perrod, PhD, Instituto de Investigação e Inovação em Saúde (i3S) 2018/19 FCUP i Study of human regulatory mutations associated with pancreatic diseases by humanizing the zebrafish genome. Inês Maria Batista da Costa, BSc Mestrado em Biologia Celular e Molecular Departamento de Biologia Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade do Porto (FCUP) Rua do Campo Alegre s/n 4169-007 Porto, Portugal [email protected] / [email protected] Tel.: +351 917457361 Supervisor