Stalingrad Pocket

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

East German TO&Es 1980-1989 V1.3

East German TO&Es 1980-1989 v1.3 BATTLEGROUP CWEG-01 (a) The East German Army (NVA) had x2 Panzer Divisions (7th & Panzer Division 1980s (a) 9th) and x4 Panzer-Grenadier Divisions (1st, 4th, 8th & 11th). These were grouped into two higher administrative formations – the BATTLEGROUPS 3rd and 5th Military Districts. Each Military District had x1 Panzer Division and x2 Panzer-Grenadier Divisions, plus Army Support BG CWEG-03 Assets. Some sources record these formations as ‘Armies’, but in x3 Panzer Regiment reality the Military Districts were administrative formations only. In war the six East German divisions would have come under the BG CWEG-04 command of five of the six Soviet Armies in Germany (28th, 2nd Guards, 8th Guards, 20th Guards & 3rd Shock Armies, but not 1st x1 Panzer-Grenadier Regiment (Tracked) Guards Army), while the East German Army support assets would form the Army Troops of 2nd Guards Army and 8th Guards Army. BG CWEG-08 Consequently, East German divisions could have Soviet Army x1 Panzer-Reconnaissance Battalion Troops in support and vice versa. The East Germans were widely regarded as the most reliable of all Warpac armies (the expression ‘There’s none so fanatical as a convert’ springs to mind) and in x1 Pioneer Battalion (b) some cases were regarded as more combat-efficient than many Soviet units in Germany. FIRE SUPPORT ELEMENTS (b) The Divisional Pioneer Battalion had a single Pioneer Company that could be considered an ME for game purposes (ME CWEG- FSE CWEG-05 14), while the rest of the battalion consisted of road-building, Divisional Artillery Regiment bridging, amphibian, position preparation and demolition equipment, which is unlikely to feature very heavily in a game. -

Military Tribunal, Indictments

MILITARY TRIBUNALS Case No. 12 THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA -against- WILHELM' VON LEEB, HUGO SPERRLE, GEORG KARL FRIEDRICH-WILHELM VON KUECHLER, JOHANNES BLASKOWITZ, HERMANN HOTH, HANS REINHARDT. HANS VON SALMUTH, KARL HOL LIDT, .OTTO SCHNmWIND,. KARL VON ROQUES, HERMANN REINECKE., WALTERWARLIMONT, OTTO WOEHLER;. and RUDOLF LEHMANN. Defendants OFFICE OF MILITARY GOVERNMENT FOR GERMANY (US) NORNBERG 1947 • PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/c6a171/ TABLE OF CONTENTS - Page INTRODUCTORY 1 COUNT ONE-CRIMES AGAINST PEACE 6 A Austria 'and Czechoslovakia 7 B. Poland, France and The United Kingdom 9 C. Denmark and Norway 10 D. Belgium, The Netherland.; and Luxembourg 11 E. Yugoslavia and Greece 14 F. The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics 17 G. The United states of America 20 . , COUNT TWO-WAR CRIMES AND CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY: CRIMES AGAINST ENEMY BELLIGERENTS AND PRISONERS OF WAR 21 A: The "Commissar" Order , 22 B. The "Commando" Order . 23 C, Prohibited Labor of Prisoners of Wal 24 D. Murder and III Treatment of Prisoners of War 25 . COUNT THREE-WAR CRIMES AND CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY: CRIMES AGAINST CIVILIANS 27 A Deportation and Enslavement of Civilians . 29 B. Plunder of Public and Private Property, Wanton Destruc tion, and Devastation not Justified by Military Necessity. 31 C. Murder, III Treatment and Persecution 'of Civilian Popu- lations . 32 COUNT FOUR-COMMON PLAN OR CONSPIRACY 39 APPENDIX A-STATEMENT OF MILITARY POSITIONS HELD BY THE DEFENDANTS AND CO-PARTICIPANTS 40 2 PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/c6a171/ INDICTMENT -

Fighting Patton Photographs

Fighting Patton Photographs [A]Mexican Punitive Expedition pershing-villa-obregon.tif: Patton’s first mortal enemy was the commander of Francisco “Pancho” Villa’s bodyguard during the Mexican Punitive Expedition. Left to right: General Álvaro Obregón, Villa, Brig. Gen. John Pershing, Capt. George Patton. [A]World War I Patton_France_1918.tif: Col. George Patton with one of his 1st Tank Brigade FT17s in France in 1918. Diepenbroick-Grüter_Otto Eitel_Friedrich.tif: Prince Freiherr von.tif: Otto Freiherr Friedrich Eitel commanded the von Diepenbroick-Grüter, 1st Guards Division in the pictured as a cadet in 1872, Argonnes. commanded the 10th Infantry Division at St. Mihiel. Gallwitz_Max von.tif: General Wilhelm_Crown Prince.tif: Crown der Artillerie Max von Prince Wilhelm commanded the Gallwitz’s army group defended region opposite the Americans. the St. Mihiel salient. [A]Morocco and Vichy France Patton_Hewitt.tif: Patton and Rear Admiral Henry Kent Hewitt, commanding Western Naval Task Force, aboard the Augusta before invading Vichy-controlled Morocco in Operation Torch. NoguesLascroux: Arriving at Fedala to negotiate an armistice at 1400 on 11 November 1942, Gen. Charles Noguès (left) is met by Col. Hobart Gay. Major General Auguste Lahoulle, Commander of French Air Forces in Morocco, is on the right. Major General Georges Lascroux, Commander in Chief of Moroccan troops, carries a briefcase. Noguès_Charles.tif: Charles Petit_Jean.tif: Jean Petit, Noguès, was Vichy commander- commanded the garrison at in-chief in Morocco. Port Lyautey. (Courtesy of Stéphane Petit) [A]The Axis Powers Patton_Monty.tif: Patton and his rival Gen. Bernard Montgomery greet each other on Sicily in July 1943. The two fought the Axis powers in Tunisia, Sicily, and the European theater. -

1940 Commandés À Plusieurs Chantiers Navals Néerlandais, Seuls Quatre Exemplaires (T-61 À T-64) Doivent Être Poursuivis, Les Autres Seront Annulés

Appendice 1 Ordre de bataille de l’Armée Rouge sur le front au 1er juin 1943 (forces principales) (pour les deux Fronts Baltes – les indications pour les autres Fronts ne sont entièrement valables qu’à partir du 1er juillet) 1er Front de la Baltique (M.M. Popov) Du sud de Parnu (Estonie) au sud de Võru (Estonie). – 1ère Armée (A.V. Kourkine) – 4e Armée (N.I. Gusev) – 7e Armée (A.N. Krutikov) – 42e Armée (V.I. Morozov) – 12e Corps Blindé (V.V. Butkov) – 15e Corps Blindé (F.N. Rudkin) Aviation subordonnée : 13e Armée Aérienne (S.D. Rybalchenko) 2e Front de la Baltique (K.A. Meretskov) Du sud de Pskov (Russie) au nord de Vitebsk (Biélorussie). – 27e Armée (N.E. Berzarine) – 34e Armée (A.I. Lopatine) – 39e Armée (A.I. Zigin) – 55e Armée (V.P. Smiridov) – 13e Corps Blindé (B.S. Bakharov) – 14e Corps Blindé (I.F. Kirichenko) – 101e Brigade Blindée lourde Aviation subordonnée : 14e Armée Aérienne (I.P. Zhuravlev) 1er Front de Biélorussie (A.I. Eremenko) De Vitebsk (Biélorussie) à Orsha (Biélorussie) – 20e Armée (P.A. Kourouchkine) – 1ère Armée de la Garde (I.M. Chistiakov) – 3e Armée de la Garde (I.G. Zakharkine) – 63e Armée (V.I. Kuznetsov) – 18e Corps Blindé (A.S. Burdeiny) Aviation subordonnée : 2e Armée Aérienne (N.F. Naumenko) 2e Front de Biélorussie (I.S. Koniev) D’Orsha (Biélorussie) à Gomel (Biélorussie). – 2e Armée de la Garde (L.A. Govorov) – 29e Armée (I.M. Managrov) – 15e Armée (I.I. Fediouninski) – 54e Armée (S.V. Roginski) – 3e Armée de Choc (M.A. Purkayev) – 7e Corps Blindé (A.G. -

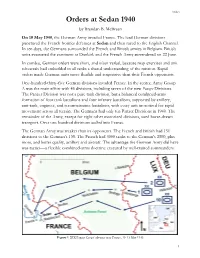

Orders at Sedan 1940 by Brendan B

Orders Orders at Sedan 1940 by Brendan B. McBreen On 10 May 1940, the German Army invaded France. The lead German divisions punctured the French frontier defenses at Sedan and then raced to the English Channel. In ten days, the Germans surrounded the French and British armies in Belgium. British units evacuated the continent at Dunkirk and the French Army surrendered on 22 June. In combat, German orders were short, and often verbal, because map exercises and unit rehearsals had embedded in all ranks a shared understanding of the mission. Rapid orders made German units more flexible and responsive than their French opponents. One-hundred-thirty-five German divisions invaded France. In the center, Army Group A was the main effort with 45 divisions, including seven of the new Panzer Divisions. The Panzer Division was not a pure tank division, but a balanced combined-arms formation of four tank battalions and four infantry battalions, supported by artillery, anti-tank, engineer, and reconnaissance battalions, with every unit motorized for rapid movement across all terrain. The Germans had only ten Panzer Divisions in 1940. The remainder of the Army, except for eight other motorized divisions, used horse-drawn transport. Over one hundred divisions walked into France. The German Army was weaker than its opponents. The French and British had 151 divisions to the German’s 135. The French had 4000 tanks to the German’s 2500, plus more, and better quality, artillery and aircraft. The advantage the German Army did have was tactics—a flexible combined-arms doctrine executed by well-trained commanders. -

A War of Reputation and Pride

A War of reputation and pride - An examination of the memoirs of German generals after the Second World War. HIS 4090 Peter Jørgen Sager Fosse Department of Archaeology, Conservation and History University of Oslo Spring 2019 1 “For the great enemy of truth is very often not the lie -- deliberate, contrived and dishonest -- but the myth -- persistent, persuasive, and unrealistic.” – John F. Kennedy, 19621 1John F. Kennedy, Yale University Commencement Address, https://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/jfkyalecommencement.htm, [01.05.2019]. 2 Acknowledgments This master would not have been written without the help and support of my mother, father, friends and my better half, thank you all for your support. I would like to thank the University Library of Oslo and the British Library in London for providing me with abundant books and articles. I also want to give huge thanks to the Military Archive in Freiburg and their employees, who helped me find the relevant materials for this master. Finally, I would like to thank my supervisor at the University of Oslo, Professor Kim Christian Priemel, who has guided me through the entire writing process from Autumn 2017. Peter Jørgen Sager Fosse, Oslo, 01.05.2019 3 Contents: Introduction………………………………………………………………………...………... 7 Chapter 1, Theory and background………………………………………………..………17 1.1 German Military Tactics…………………………………………………..………. 17 1.1.1 Blitzkrieg, Kesselschlacht and Schwerpunkt…………………………………..……. 17 1.1.2 Examples from early campaigns……………………………………………..……… 20 1.2 The German attack on the USSR (1941)……………………………..…………… 24 1.2.1 ‘Vernichtungskrieg’, war of annihilation………………………………...………….. 24 1.2.2 Operation Barbarossa………………………………………………..……………… 28 1.2.3 Operation Typhoon…………………………………………………..………………. 35 1.2.4 The strategic situation, December 1941…………………………….………………. -

WHO's WHO in the WAR in EUROPE the War in Europe 7 CHARLES DE GAULLE

who’s Who in the War in Europe (National Archives and Records Administration, 342-FH-3A-20068.) POLITICAL LEADERS Allies FRANKLIN DELANO ROOSEVELT When World War II began, many Americans strongly opposed involvement in foreign conflicts. President Roosevelt maintained official USneutrality but supported measures like the Lend-Lease Act, which provided invaluable aid to countries battling Axis aggression. After Pearl Harbor and Germany’s declaration of war on the United States, Roosevelt rallied the country to fight the Axis powers as part of the Grand Alliance with Great Britain and the Soviet Union. (Image: Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-128765.) WINSTON CHURCHILL In the 1930s, Churchill fiercely opposed Westernappeasement of Nazi Germany. He became prime minister in May 1940 following a German blitzkrieg (lightning war) against Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. He then played a pivotal role in building a global alliance to stop the German juggernaut. One of the greatest orators of the century, Churchill raised the spirits of his countrymen through the war’s darkest days as Germany threatened to invade Great Britain and unleashed a devastating nighttime bombing program on London and other major cities. (Image: Library of Congress, LC-USW33-019093-C.) JOSEPH STALIN Stalin rose through the ranks of the Communist Party to emerge as the absolute ruler of the Soviet Union. In the 1930s, he conducted a reign of terror against his political opponents, including much of the country’s top military leadership. His purge of Red Army generals suspected of being disloyal to him left his country desperately unprepared when Germany invaded in June 1941. -

The Issues of War with Japan Coverage in the Presidential Project «Fundamental Multi-Volume Work» the Great Patriotic War of 1941 - 1945 «»

Vyatcheslav Zimonin Captain (Russia NAVY) Doctor of Historical Sciences, Professor of Military University, Honored Scientist Of The Russian Federation and Academy of Natural Sciences The issues of war with Japan coverage in the Presidential project «Fundamental multi-volume work» The Great Patriotic War of 1941 - 1945 «» Fundamental multi-volume work «The Great Patriotic War of 1941-1945» is being developed in accordance with the Decree № 240-рп of May 5, 2008 of the President of the Russian Federation. The work is developed under the organizational leadership of the main drafting committee headed by the Minister of Defense of the Russian Federation Army General Sergey Shoigu. Major General V.A. Zolotarev, well-known Russian scientist, Doctor of Historical and Legal Sciences, Professor, Academician of the Academy of Natural Sciences, State Councilor of the Russian Federation Deputy Chairman of the GRK is appointed as scientific director of the multi-volume work. Fundamental structure of a multivolume work: Volume 1 - «The main facts of the war,» Volume 2 - «The origin and the beginning of the war» Volume 3 - «Battles and actions that changed the course of the war,» Volume 4 - «Freeing of the USSR, 1944 « Volume 5 - «The final victory. Final operations of World War II in Europe. War with Japan « Volume 6 - «The Secret War. Intelligence and counterintelligence in the Great Patriotic War « Volume 7 - «Economy and weapons of war» Volume 8 - «Foreign policy and diplomacy of the Soviet Union during the war» Volume 9 - «Allies of the USSR in the war» Volume 10 - «The power, society and war» Volume 11 - «Policy and Strategy of Victory. -

Cold Vs. Hot War: a Model for Building Conceptual Knowledge in History Geoffrey Scheurman

Social Education 76(1), pp 32–37 ©2012 National Council for the Social Studies Cold vs. Hot War: A Model for Building Conceptual Knowledge in History Geoffrey Scheurman Students often report that social studies is their most boring and least favorite subject. habits of mind unfolds, a by-product is As a child, Woodrow Wilson was bored by history, later describing his early studies the development of human intellectual as “one damn fact after another.” Of course, Wilson went on to become an eminent constructions we call concepts. In his- historian, but only after he learned to reach beyond the “closed catechism” of “ques- tory, a concept such as “revolution” is tions already answered”1 to the exciting themes and processes that gave those facts seldom black or white. Asking the right meaning. Central to Wilson’s discovery were questions that guide inquiry in the field, analytical questions leads to a continuum procedures that experts use to carry out this inquiry, and generalizations, principles of generalizations about revolutionary or theories that frame the results of that process. Together, these big ideas comprise conditions. Furthermore, it invokes a the conceptual backbone that holds the narratives of history together. Taking time to set of disciplinary processes which identify the big ideas in a lesson, unit, or course, insures that teachers do not drown themselves exist along a continuum. For students in too much minutiae. And coming to grips with essential concepts provides example, sources do not exist as simply the best chance for students to construct deep knowledge structures that will transfer credible or not credible; they are “more to contexts beyond the classroom. -

Ronald Macarthur Hirst Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt4f59r673 No online items Register of the Ronald MacArthur Hirst papers Processed by Brad Bauer Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] © 2008 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Register of the Ronald MacArthur 93044 1 Hirst papers Register of the Ronald MacArthur Hirst papers Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California Processed by: Brad Bauer Date Completed: 2008 Encoded by: Elizabeth Konzak and David Jacobs © 2008 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Ronald MacArthur Hirst papers Dates: 1929-2004 Collection number: 93044 Creator: Hirst, Ronald MacArthur, 1923- Collection Size: 102 manuscript boxes, 4 card files, 2 oversize boxes (43.2 linear feet) Repository: Hoover Institution Archives Stanford, California 94305-6010 Abstract: The Ronald MacArthur Hirst papers consist largely of material collected and created by Hirst over the course of several decades of research on topics related to the history of World War II and the Cold War, including the Battle of Stalingrad, the Allied landing at Normandy on D-Day, American aerial operations, and the Berlin Airlift of 1948-1949, among other topics. Included are writings, correspondence, biographical data, notes, copies of government documents, printed matter, maps, and photographs. Physical location: Hoover Institution Archives Languages: Languages represented in the collection: English, German Access Collection is open for research. The Hoover Institution Archives only allows access to copiesof audiovisual items. To listen to sound recordings or to view videos or films during your visit, please contact the Archives at least two working days before your arrival. -

Second World War Deception Lessons Learned for Today’S Joint Planner

Air University Joseph J. Redden, Lt Gen, Commander Air Command and Staff College John W. Rosa, Col, Commandant James M. Norris, Col, Dean Stuart Kenney, Maj, Series Editor Richard Muller, PhD, Essay Advisor Air University Press Robert Lane, Director John Jordan, Content Editor Peggy Smith, Copy Editor Prepress Production: Mary Ferguson Cover Design: Daniel Armstrong Please send inquiries or comments to: Editor The Wright Flyer Papers Air Command and Staff College (ACSC/DER) 225 Chennault Circle Bldg 1402 Maxwell AFB AL 36112-6426 Tel: (334) 953-2308 Fax: (334) 953-2292 Internet: [email protected] AIR COMMAND AND STAFF COLLEGE AIR UNIVERSITY Second World War Deception Lessons Learned for Today’s Joint Planner Donald J. Bacon Major, USAF Air Command and Staff College Wright Flyer Paper No. 5 MAXWELL AIR FORCE BASE, ALABAMA December 1998 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. ii Foreword It is my great pleasure to present another of the Wright Flyer Papers series. In this series, Air Command and Staff College (ACSC) recognizes and publishes the “best of the best” student research projects from the prior academic year. The ACSC re - search program encourages our students to move beyond the school’s core curriculum in their own professional development and in “advancing aerospace power.” The series title reflects our desire to perpetuate the pioneering spirit embodied in earlier generations of airmen. -

Subject Listing of Numbered Documents in M1934, OSS WASHINGTON SECRET INTELLIGENCE/SPECIAL FUNDS RECORDS, 1942-46

Subject Listing of Numbered Documents in M1934, OSS WASHINGTON SECRET INTELLIGENCE/SPECIAL FUNDS RECORDS, 1942-46 Roll # Doc # Subject Date To From 1 0000001 German Cable Company, D.A.T. 4/12/1945 State Dept.; London, American Maritime Delegation, Horta American Embassy, OSS; (Azores), (McNiece) Washington, OSS 1 0000002 Walter Husman & Fabrica de Produtos Alimonticios, "Cabega 5/29/1945 State Dept.; OSS Rio de Janeiro, American Embassy Branca of Sao Paolo 1 0000003 Contraband Currency & Smuggling of Wrist Watches at 5/17/1945 Washington, OSS Tangier, American Mission Tangier 1 0000004 Shipment & Movement of order for watches & Chronographs 3/5/1945 Pierce S.A., Switzerland Buenos Aires, American Embassy from Switzerland to Argentine & collateral sales extended to (Manufactures) & OSS (Vogt) other venues/regions (Washington) 1 0000005 Brueghel artwork painting in Stockholm 5/12/1945 Stockholm, British Legation; London, American Embassy London, American Embassy & OSS 1 0000006 Investigation of Matisse painting in possession of Andre Martin 5/17/1945 State Dept.; Paris, British London, American Embassy of Zurich Embassy, London, OSS, Washington, Treasury 1 0000007 Rubens painting, "St. Rochus," located in Stockholm 5/16/1945 State Dept.; Stockholm, British London, American Embassy Legation; London, Roberts Commission 1 0000007a Matisse painting held in Zurich by Andre Martin 5/3/1945 State Dept.; Paris, British London, American Embassy Embassy 1 0000007b Interview with Andre Martiro on Matisse painting obtained by 5/3/1945 Paris, British Embassy London, American Embassy Max Stocklin in Paris (vice Germans allegedly) 1 0000008 Account at Banco Lisboa & Acores in name of Max & 4/5/1945 State Dept.; Treasury; Lisbon, London, American Embassy (Peterson) Marguerite British Embassy 1 0000008a Funds transfer to Regerts in Oporto 3/21/1945 Neutral Trade Dept.