Risk Assessment Presentation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iaea International Fact Finding Expert Mission of the Fukushima Dai-Ichi Npp Accident Following the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami

IAEA Original English MISSION REPORT THE GREAT EAST JAPAN EARTHQUAKE EXPERT MISSION IAEA INTERNATIONAL FACT FINDING EXPERT MISSION OF THE FUKUSHIMA DAI-ICHI NPP ACCIDENT FOLLOWING THE GREAT EAST JAPAN EARTHQUAKE AND TSUNAMI Tokyo, Fukushima Dai-ichi NPP, Fukushima Dai-ni NPP and Tokai Dai-ni NPP, Japan 24 May – 2 June 2011 IAEA MISSION REPORT DIVISION OF NUCLEAR INSTALLATION SAFETY DEPARTMENT OF NUCLEAR SAFETY AND SECURITY IAEA Original English IAEA REPORT THE GREAT EAST JAPAN EARTHQUAKE EXPERT MISSION IAEA INTERNATIONAL FACT FINDING EXPERT MISSION OF THE FUKUSHIMA DAI-ICHI NPP ACCIDENT FOLLOWING THE GREAT EAST JAPAN EARTHQUAKE AND TSUNAMI REPORT TO THE IAEA MEMBER STATES Tokyo, Fukushima Dai-ichi NPP, Fukushima Dai-ni NPP and Tokai Dai-ni NPP, Japan 24 May – 2 June 2011 i IAEA ii IAEA REPORT THE GREAT EAST JAPAN EARTHQUAKE EXPERT MISSION IAEA INTERNATIONAL FACT FINDING EXPERT MISSION OF THE FUKUSHIMA DAI-ICHI NPP ACCIDENT FOLLOWING THE GREAT EAST JAPAN EARTHQUAKE AND TSUNAMI Mission date: 24 May – 2 June 2011 Location: Tokyo, Fukushima Dai-ichi, Fukushima Dai-ni and Tokai Dai-ni, Japan Facility: Fukushima and Tokai nuclear power plants Organized by: International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) IAEA Review Team: WEIGHTMAN, Michael HSE, UK, Team Leader JAMET, Philippe ASN, France, Deputy Team Leader LYONS, James E. IAEA, NSNI, Director SAMADDAR, Sujit IAEA, NSNI, Head, ISCC CHAI, Guohan People‘s Republic of China CHANDE, S. K. AERB, India GODOY, Antonio Argentina GORYACHEV, A. NIIAR, Russian Federation GUERPINAR, Aybars Turkey LENTIJO, Juan Carlos CSN, Spain LUX, Ivan HAEA, Hungary SUMARGO, Dedik E. BAPETEN, Indonesia iii IAEA SUNG, Key Yong KINS, Republic of Korea UHLE, Jennifer USNRC, USA BRADLEY, Edward E. -

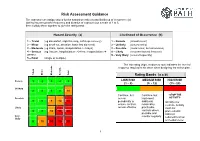

Risk Assessment Guidance

Risk Assessment Guidance The assessor can assign values for the hazard severity (a) and likelihood of occurrence (b) (taking into account the frequency and duration of exposure) on a scale of 1 to 5, then multiply them together to give the rating band: Hazard Severity (a) Likelihood of Occurrence (b) 1 – Trivial (eg discomfort, slight bruising, self-help recovery) 1 – Remote (almost never) 2 – Minor (eg small cut, abrasion, basic first aid need) 2 – Unlikely (occurs rarely) 3 – Moderate (eg strain, sprain, incapacitation > 3 days) 3 – Possible (could occur, but uncommon) 4 – Serious (eg fracture, hospitalisation >24 hrs, incapacitation >4 4 – Likely (recurrent but not frequent) weeks) 5 – Very likely (occurs frequently) 5 – Fatal (single or multiple) The risk rating (high, medium or low) indicates the level of response required to be taken when designing the action plan. Trivial Minor Moderate Serious Fatal Rating Bands (a x b) Remote 1 2 3 4 5 LOW RISK MEDIUM RISK HIGH RISK (1 – 8) (9 - 12) (15 - 25) Unlikely 2 4 6 8 10 Continue, but Continue, but -STOP THE Possible review implement ACTIVITY- 3 6 9 12 15 periodically to additional Identify new ensure controls reasonably controls. Activity Likely remain effective practicable must not controls where 4 8 12 16 20 proceed until possible and risks are Very monitor regularly reduced to a low likely 5 10 15 20 25 or medium level 1 Risk Assessments There are a number of explanations needed in order to understand the process and the form used in this example: HAZARD: Anything that has the potential to cause harm. -

Personal Protective Equipment ______

Personal Protective Equipment __________________________________________________________________ Page Introduction Purpose ………. 2 Background ………. 2 Who’s Covered? …….... 3 Explanation of Key Terms ………. 3 How It Works Hazard Assessment ………. 4 Hazard Control ………. 5 Training ………. 5 Documentation ………. 6 Appendix A – Hazard Assessment/Training Certification Form ………. 7 B – Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) Guidelines ………. 8 University of Arizona Risk Management & Safety Health and Safety Instruction April 2007 ________________________________ Page 2 Health and Safety Instruction ______________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION Purpose The purpose of this Health and Safety Instruction (HSI) is to protect employees from hazards in the workplace by using personal protective equipment to supplement other primary hazard controls. Background Hazards exist in every workplace in many different forms: sharp edges, falling objects, flying sparks, chemicals, noise and a myriad of other potentially dangerous situations. Controlling hazards with engineering and administrative controls is the best way to protect employees When these controls are not feasible or do not provide sufficient protection, personal protective equipment (PPE) must be use. In line with this rational for controlling or eliminating workplace hazards, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) issued the Personal Protective Equipment standard, also know as "The PPE Standard." Under this standard, the University is required to: • Conduct hazard assessments to determine if PPE is necessary to protect employees and certify in writing that assessments have been performed. • Select appropriate PPE, where necessary. • Provide employees training on proper care, use and limitations of the selected PPE. • Ensure the PPE is properly used. This HSI, developed by Risk Management & Safety outlines the minimum requirements to protect employees from hazards in the workplace by using personal protective equipment to supplement other primary hazard controls. -

Risk Management for a Small Business Participant Guide

Risk Management for a Small Business Participant Guide Table of Contents Welcome ................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 What Do You Know? Risk Management for a Small Business ........................................................................................ 4 Pre-Test .................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Risk Management ................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Discussion Point #1: Risks from Positive Situations .......................................................................................................... 6 Internal Risks ........................................................................................................................................................................ 6 Discussion Point #2: Internal Risks ..................................................................................................................................... 8 External Risks ....................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Discussion Point #3: External Risks ................................................................................................................................... -

Operational Risk Management Guide

OPERATIONAL RISK MANAGEMENT GUIDE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FOREST SERVICE 2020 Last Updated 02/26/2020 RISK MANAGEMENT COUNCIL IN COOPERATION WITH THE OFFICE OF SAFETY & OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH and THE NATIONAL AVIATION SAFETY COUNCIL Contents Contents ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................................................. i Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................... 1 What is Operational Risk Management? ................................................................................................................... 1 The Terminology of ORM ................................................................................................................................................ 1 Principles of ORM Application ........................................................................................................................................... 6 The Five-Step ORM Process ................................................................................................................................................ 7 Step 1: Identify Hazards .................................................................................................................................................. -

March 2011 Earthquake, Tsunami and Fukushima Nuclear Accident Impacts on Japanese Agri-Food Sector

Munich Personal RePEc Archive March 2011 earthquake, tsunami and Fukushima nuclear accident impacts on Japanese agri-food sector Bachev, Hrabrin January 2015 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/61499/ MPRA Paper No. 61499, posted 21 Jan 2015 14:37 UTC March 2011 earthquake, tsunami and Fukushima nuclear accident impacts on Japanese agri-food sector Hrabrin Bachev1 I. Introduction On March 11, 2011 the strongest recorded in Japan earthquake off the Pacific coast of North-east of the country occurred (also know as Great East Japan Earthquake, 2011 Tohoku earthquake, and the 3.11 Earthquake) which triggered a powerful tsunami and caused a nuclear accident in one of the world’s largest nuclear plant (Fukushima Daichi Nuclear Plant Station). It was the first disaster that included an earthquake, a tsunami, and a nuclear power plant accident. The 2011 disasters have had immense impacts on people life, health and property, social infrastructure and economy, natural and institutional environment, etc. in North-eastern Japan and beyond [Abe, 2014; Al-Badri and Berends, 2013; Biodiversity Center of Japan, 2013; Britannica, 2014; Buesseler, 2014; FNAIC, 2013; Fujita et al., 2012; IAEA, 2011; IBRD, 2012; Kontar et al., 2014; NIRA, 2013; TEPCO, 2012; UNEP, 2012; Vervaeck and Daniell, 2012; Umeda, 2013; WHO, 2013; WWF, 2013]. We have done an assessment of major social, economic and environmental impacts of the triple disaster in another publication [Bachev, 2014]. There have been numerous publications on diverse impacts of the 2011 disasters including on the Japanese agriculture and food sector [Bachev and Ito, 2013; JA-ZENCHU, 2011; Johnson, 2011; Hamada and Ogino, 2012; MAFF, 2012; Koyama, 2013; Sekizawa, 2013; Pushpalal et al., 2013; Liou et al., 2012; Murayama, 2012; MHLW, 2013; Nakanishi and Tanoi, 2013; Oka, 2012; Ujiie, 2012; Yasunaria et al., 2011; Watanabe A., 2011; Watanabe N., 2013]. -

COVID-19: Make It the Last Pandemic

COVID-19: Make it the Last Pandemic Disclaimer: The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city of area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Report Design: Michelle Hopgood, Toronto, Canada Icon Illustrator: Janet McLeod Wortel Maps: Taylor Blake COVID-19: Make it the Last Pandemic by The Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness & Response 2 of 86 Contents Preface 4 Abbreviations 6 1. Introduction 8 2. The devastating reality of the COVID-19 pandemic 10 3. The Panel’s call for immediate actions to stop the COVID-19 pandemic 12 4. What happened, what we’ve learned and what needs to change 15 4.1 Before the pandemic — the failure to take preparation seriously 15 4.2 A virus moving faster than the surveillance and alert system 21 4.2.1 The first reported cases 22 4.2.2 The declaration of a public health emergency of international concern 24 4.2.3 Two worlds at different speeds 26 4.3 Early responses lacked urgency and effectiveness 28 4.3.1 Successful countries were proactive, unsuccessful ones denied and delayed 31 4.3.2 The crisis in supplies 33 4.3.3 Lessons to be learnt from the early response 36 4.4 The failure to sustain the response in the face of the crisis 38 4.4.1 National health systems under enormous stress 38 4.4.2 Jobs at risk 38 4.4.3 Vaccine nationalism 41 5. -

Hot Work Permit Program

Hot Work Permit Program Risk Management 1 Hot Work Permit Program Risk Management July 2019 Table of Contents I. Program Goals and Objectives ...................................................................................................................3 II. Scope and Application ................................................................................................................................3 III. Definitions ..................................................................................................................................................3 IV. Responsibilities ...........................................................................................................................................4 V. Record Keeping ..........................................................................................................................................4 VI. Procedures .................................................................................................................................................5 VII. Hot Work Permit Form ...............................................................................................................................8 VIII. Regulatory Authority and Related Information .........................................................................................9 IX. Contact .......................................................................................................................................................9 2 Hot Work Permit Program Risk Management -

(CRSI) Steering Committee Final Report — a Roadmap to Increased Community Resilience

Community Resilience System Initiative (CRSI) Steering Committee Final Report — a Roadmap to Increased Community Resilience August 2011 CRSI Community Resilience System Initiative Community Resilience System Initiative (CRSI) Steering Committee Final Report — a Roadmap to Increased Community Resilience August 2011 Developed and Convened by the This material is based upon work supported by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security under U.S. Department of Energy Interagency Agreement 43WT10301. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Community Resilience System Initiative Final Report • August 2011 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................................... v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... vii I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................. 1 Community Resilience in Action ..................................................................................................... 2 Message from the Community Resilience System Initiative Steering Committee Chair ....................................................................................................................... -

Guide Six Steps to Risk Management

Guide Six step to risk management www.worksafe.nt.gov.au Disclaimer This publication contains information regarding work health and safety. It includes some of your obligations under the Work Health and Safety (National Uniform Legislation) Act – the WHS Act – that NT WorkSafe administers. The information provided is a guide only and must be read in conjunction with the appropriate legislation to ensure you understand and comply with your legal obligations. Acknowledgement This guide is based on material produced by WorkSafe ACT at www.worksafe.act.gov.au Version: 1.2 Publish date: September 2018 Contents Introduction ..............................................................................................................................4 Good management practice.....................................................................................................4 Defining Hazard and Risk.....................................................................................................5 Systematic approach to the management of Hazards and associated Risks ......................5 Step 1: Hazard identification ....................................................................................................6 Examples of Hazards ...........................................................................................................6 Step 2: Risk identification.........................................................................................................7 Examples of risk identification ..............................................................................................7 -

Permit to Work Systems

Loss prevention standards Permit to Work Systems High risk work can become even more hazardous due to unsafe conditions and human error. Formal controls, such as a permit to work system, must be followed by everyone and enforced properly to be effective. Aviva: Public Permit to Work Systems Introduction The aim of a permit to work system is to remove both unsafe conditions and human error from a high-risk process, by imposing a formal system detailing exactly what work is to be done and when and how to undertake the job safely. Permit to work systems are used where the potential hazards are significant and a formal documented system is required to control the work and minimise the risk of personal injury, loss or damage. Operation of the Permit to Work System Examples of work in which a permit to work system should be used include: • Entry into confined spaces • Work involving the splitting or breaking into of pressurised pipelines • Work on high voltage electrical systems above 3,000 volts • Hot work, e.g. welding, brazing, soldering, etc. • Work in isolated situations or where access is difficult • Work at height • Work near to, or requiring the use of highly flammable/explosive/toxic substances • Fumigation operations using gases • High-risk operations involving contractors, such as excavation works, or demolition works Designing the Permit to Work System Permit to work systems demand robust, formal and effective controls in place to prevent danger, as well as good standards of organisation to ensure compliance. - include fire extinguishers being available for hot work, or harnesses and resuscitation equipment available when entering confined spaces. -

Accident Knowledge and Emergency Management

Ris0-R-945(EN) DK9700056 Accident Knowledge and Emergency Management Birgitte Rasmussen, Carsten D. Gr0nberg Ris0 National Laboratory, Roskilde, Denmark March 1997 VOL 2 p III 1 2 Accident Knowledge and Emergency Management Birgitte Rasmussen, Carsten D. Gr0nberg Ris0 National Laboratory, Roskilde, Denmark March 1997 Abstract. The report contains an overall frame for transformation of knowledge and experience from risk analysis to emergency education. An accident model has been developed to describe the emergency situation. A key concept of this model is uncontrolled flow of energy (UFOE), essential ele- ments are the state, location and movement of the energy (and mass). A UFOE can be considered as the driving force of an accident, e.g., an explosion, a fire, a release of heavy gases. As long as the energy is confined, i.e. the location and movement of the energy are under control, the situation is safe, but loss of con- finement will create a hazardous situation that may develop into an accident. A domain model has been developed for representing accident and emergency scenarios occurring in society. The domain model uses three main categories: status, context and objectives. A domain is a group of activities with allied goals and elements and ten specific domains have been investigated: process plant, storage, nuclear power plant, energy distribution, marine transport of goods, marine transport of people, aviation, transport by road, transport by rail and natural disasters. Totally 25 accident cases were consulted and information was extracted for filling into the schematic representations with two to four cases pr. specific domain. The work described in this report is financially supported by EUREKA MEM- brain (Major Emergency Management) project running 1993-1998.