A First View of the Future of the Canada Pension Plan Disability Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wednesday, October 1, 1997

CANADA VOLUME 135 S NUMBER 008 S 1st SESSION S 36th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Wednesday, October 1, 1997 Speaker: The Honourable Gilbert Parent CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) The House of Commons Debates are also available on the Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire at the followingaddress: http://www.parl.gc.ca 323 HOUSE OF COMMONS Wednesday, October 1, 1997 The House met at 2 p.m. Columbians are crying out for federal leadership and this govern- ment is failing them miserably. _______________ Nowhere is this better displayed than in the Liberals’ misman- Prayers agement of the Pacific salmon dispute over the past four years. The sustainability of the Pacific salmon fishery is at stake and the _______________ minister of fisheries sits on his hands and does nothing except criticize his own citizens. D (1400) Having witnessed the Tory government destroy the Atlantic The Speaker: As is our practice on Wednesday we will now sing fishery a few years ago, this government seems intent on doing the O Canada, and we will be led by the hon. member for Souris— same to the Pacific fishery. Moose Mountain. It is a simple case of Liberal, Tory, same old incompetent story. [Editor’s Note: Members sang the national anthem] This government had better wake up to the concerns of British Columbians. A good start would be to resolve the crisis in the _____________________________________________ salmon fishery before it is too late. * * * STATEMENTS BY MEMBERS TOM EDWARDS [English] Ms. Judi Longfield (Whitby—Ajax, Lib.): Mr. Speaker, I rise today to recognize the outstanding municipal career of Mr. -

George Committees Party Appointments P.20 Young P.28 Primer Pp

EXCLUSIVE POLITICAL COVERAGE: NEWS, FEATURES, AND ANALYSIS INSIDE HARPER’S TOOTOO HIRES HOUSE LATE-TERM GEORGE COMMITTEES PARTY APPOINTMENTS P.20 YOUNG P.28 PRIMER PP. 30-31 CENTRAL P.35 TWENTY-SEVENTH YEAR, NO. 1322 CANADA’S POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT NEWSWEEKLY MONDAY, FEBRUARY 22, 2016 $5.00 NEWS SENATE REFORM NEWS FINANCE Monsef, LeBlanc LeBlanc backs away from Morneau to reveal this expected to shed week Trudeau’s whipped vote on assisted light on deficit, vision for non- CIBC economist partisan Senate dying bill, but Grit MPs predicts $30-billion BY AbbaS RANA are ‘comfortable,’ call it a BY DEREK ABMA Senators are eagerly waiting to hear this week specific details The federal government is of the Trudeau government’s plan expected to shed more light on for a non-partisan Red Cham- Charter of Rights issue the size of its deficit on Monday, ber from Government House and one prominent economist Leader Dominic LeBlanc and Members of the has predicted it will be at least Democratic Institutions Minister Joint Committee $30-billion—about three times Maryam Monsef. on Physician- what the Liberals promised dur- The appearance of the two Assisted ing the election campaign—due to ministers at the Senate stand- Suicide, lower-than-expected tax revenue ing committee will be the first pictured at from a slow economy and the time the government has pre- a committee need for more fiscal stimulus. sented detailed plans to reform meeting on the “The $10-billion [deficit] was the Senate. Also, this is the first Hill. The Hill the figure that was out there official communication between Times photograph based on the projection that the the House of Commons and the by Jake Wright economy was growing faster Senate on Mr. -

Core 1..146 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 8.00)

CANADA House of Commons Debates VOLUME 140 Ï NUMBER 098 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 38th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, May 13, 2005 Speaker: The Honourable Peter Milliken CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) All parliamentary publications are available on the ``Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire´´ at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 5957 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, May 13, 2005 The House met at 10 a.m. Parliament on February 23, 2005, and Bill C-48, an act to authorize the Minister of Finance to make certain payments, shall be disposed of as follows: 1. Any division thereon requested before the expiry of the time for consideration of Government Orders on Thursday, May 19, 2005, shall be deferred to that time; Prayers 2. At the expiry of the time for consideration of Government Orders on Thursday, May 19, 2005, all questions necessary for the disposal of the second reading stage of (1) Bill C-43 and (2) Bill C-48 shall be put and decided forthwith and successively, Ï (1000) without further debate, amendment or deferral. [English] Ï (1010) MESSAGE FROM THE SENATE The Speaker: Does the hon. government House leader have the The Speaker: I have the honour to inform the House that a unanimous consent of the House for this motion? message has been received from the Senate informing this House Some hon. members: Agreed. that the Senate has passed certain bills, to which the concurrence of this House is desired. Some hon. members: No. Mr. Jay Hill (Prince George—Peace River, CPC): Mr. -

GETTING IT RIGHT for CANADIANS: the DISABILITY TAX CREDIT Standing Committee on Human Resources Development and the Status of Pe

HOUSE OF COMMONS CANADA GETTING IT RIGHT FOR CANADIANS: THE DISABILITY TAX CREDIT Standing Committee on Human Resources Development and the Status of Persons with Disabilities Judi Longfield, M.P. Chair Carolyn Bennett, M.P. Chair Sub-Committee on the Status of Persons with Disabilities March 2002 The Speaker of the House hereby grants permission to reproduce this document, in whole or in part for use in schools and for other purposes such as private study, research, criticism, review or newspaper summary. Any commercial or other use or reproduction of this publication requires the express prior written authorization of the Speaker of the House of Commons. If this document contains excerpts or the full text of briefs presented to the Committee, permission to reproduce these briefs, in whole or in part, must be obtained from their authors. Also available on the Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire: http://www.parl.gc.ca Available from Public Works and Government Services Canada — Publishing, Ottawa, Canada K1A 0S9 GETTING IT RIGHT FOR CANADIANS: THE DISABILITY TAX CREDIT Standing Committee on Human Resources Development and the Status of Persons with Disabilities Judi Longfield, M.P. Chair Carolyn Bennett, M.P. Chair Sub-Committee on the Status of Persons with Disabilities March 2002 STANDING COMMITTEE ON HUMAN RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT AND THE STATUS OF PERSONS WITH DISABILITIES CHAIR Judi Longfield VICE-CHAIRS Diane St-Jacques Carol Skelton MEMBERS Eugène Bellemare Serge Marcil Paul Crête Joe McGuire Libby Davies Anita Neville Raymonde Folco -

Map of Canada, Official Results of the 38Th General Election – PDF Format

2 5 3 2 a CANDIDATES ELECTED / CANDIDATS ÉLUS Se 6 ln ln A nco co C Li in R L E ELECTORAL DISTRICT PARTY ELECTED CANDIDATE ELECTED de ELECTORAL DISTRICT PARTY ELECTED CANDIDATE ELECTED C er O T S M CIRCONSCRIPTION PARTI ÉLU CANDIDAT ÉLU C I bia C D um CIRCONSCRIPTION PARTI ÉLU CANDIDAT ÉLU É ol C A O N C t C A H Aler 35050 Mississauga South / Mississauga-Sud Paul John Mark Szabo N E !( e A N L T 35051 Mississauga--Streetsville Wajid Khan A S E 38th GENERAL ELECTION R B 38 ÉLECTION GÉNÉRALE C I NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR 35052 Nepean--Carleton Pierre Poilievre T A I S Q Phillip TERRE-NEUVE-ET-LABRADOR 35053 Newmarket--Aurora Belinda Stronach U H I s In June 28, 2004 E T L 28 juin, 2004 É 35054 Niagara Falls Hon. / L'hon. Rob Nicholson E - 10001 Avalon Hon. / L'hon. R. John Efford B E 35055 Niagara West--Glanbrook Dean Allison A N 10002 Bonavista--Exploits Scott Simms I Z Niagara-Ouest--Glanbrook E I L R N D 10003 Humber--St. Barbe--Baie Verte Hon. / L'hon. Gerry Byrne a 35056 Nickel Belt Raymond Bonin E A n L N 10004 Labrador Lawrence David O'Brien s 35057 Nipissing--Timiskaming Anthony Rota e N E l n e S A o d E 10005 Random--Burin--St. George's Bill Matthews E n u F D P n d ely E n Gre 35058 Northumberland--Quinte West Paul Macklin e t a s L S i U a R h A E XEL e RÉSULTATS OFFICIELS 10006 St. -

Court File No.: CV-18-00605134-00CP ONTARIO

Court File No.: CV-18-00605134-00CP ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE BETWEEN: MICKY GRANGER Plaintiff - and - HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN IN RIGHT OF THE PROVINCE OF ONTARIO Defendant Proceeding under the Class Proceedings Act, 1992 MOTION RECORD OF THE PLAINTIFF (CERTIFICATION) (Returnable November 27 & 28, 2019) VOLUME II of II March 18, 2019 GOLDBLATT PARTNERS LLP 20 Dundas Street West, Suite 1039 Toronto ON M5G 2C2 Jody Brown LS# 58844D Tel: 416-979-4251 / Fax: 416-591-7333 Email: [email protected] Geetha Philipupillai LS# 74741S Tel.: 416-979-4252 / Fax: 416-591-7333 Email: [email protected] Lawyers for the Plaintiff - 2 TO: HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN IN RIGHT - OF THE PROVINCE OF ONTARIO Crown Law Office – Civil Law 720 Bay Street, 8th Floor Toronto, ON, M5G 2K1 Amy Leamen LS#: 49351R Tel: 416.326.4153 / Fax: 416.326.4181 Lawyers for the Defendant TABLE OF CONTENTS TAB DESCRIPTION PG # 1. Notice of Motion (Returnable November 27 and 28, 2019) 1 A. Appendix “A” – List of Common Issues 6 2. Affidavit of Micky Granger (Unsworn) 8 3. Affidavit of Tanya Atherfold-Desilva sworn March 18, 2019 12 A. Exhibit “A”: Office of the Independent Police Review Director – 20 Systemic Review Report dated July 2016 B. Exhibit “B”: Office of the Independent Police Review Director - 126 Executive Summary and Recommendations dated July 2016 C. Exhibit “C”: Office of the Independent Police Review Director – Terms of 142 Reference as of March 2019 D. Exhibit “D”: Affidavit of David D.J. Truax sworn August 30, 2016 146 E. Exhibit “E”: Centre of Forensic Investigators & Submitters Technical 155 Information Sheets effective April 2, 2015 F. -

Wednesday, April 24, 1996

CANADA VOLUME 134 S NUMBER 032 S 2nd SESSION S 35th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Wednesday, April 24, 1996 Speaker: The Honourable Gilbert Parent CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) The House of Commons Debates are also available on the Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 1883 HOUSE OF COMMONS Wednesday, April 24, 1996 The House met at 2 p.m. [English] _______________ LIBERAL PARTY OF CANADA Prayers Mr. Ken Epp (Elk Island, Ref.): Mr. Speaker, voters need accurate information to make wise decisions at election time. With _______________ one vote they are asked to choose their member of Parliament, select the government for the term, indirectly choose the Prime The Speaker: As is our practice on Wednesdays, we will now Minister and give their approval to a complete all or nothing list of sing O Canada, which will be led by the hon. member for agenda items. Vancouver East. During an election campaign it is not acceptable to say that the [Editor’s Note: Whereupon members sang the national anthem.] GST will be axed with pledges to resign if it is not, to write in small print that it will be harmonized, but to keep it and hide it once the _____________________________________________ election has been won. It is not acceptable to promise more free votes if all this means is that the status quo of free votes on private members’ bills will be maintained. It is not acceptable to say that STATEMENTS BY MEMBERS MPs will be given more authority to represent their constituents if it means nothing and that MPs will still be whipped into submis- [English] sion by threats and actions of expulsion. -

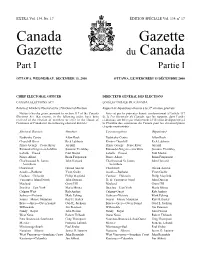

Canada Gazette, Part I, Extra

EXTRA Vol. 134, No. 17 ÉDITION SPÉCIALE Vol. 134, no 17 Canada Gazette Gazette du Canada Part I Partie I OTTAWA, WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 13, 2000 OTTAWA, LE MERCREDI 13 DÉCEMBRE 2000 CHIEF ELECTORAL OFFICER DIRECTEUR GÉNÉRAL DES ÉLECTIONS CANADA ELECTIONS ACT LOI ÉLECTORALE DU CANADA Return of Members Elected at the 37th General Election Rapport de députés(es) élus(es) à la 37e élection générale Notice is hereby given, pursuant to section 317 of the Canada Avis est par les présentes donné, conformément à l’article 317 Elections Act, that returns, in the following order, have been delaLoi électorale du Canada, que les rapports, dans l’ordre received of the election of members to serve in the House of ci-dessous, ont été reçus relativement à l’élection de députés(es) à Commons of Canada for the following electoral districts: la Chambre des communes du Canada pour les circonscriptions ci-après mentionnées : Electoral Districts Members Circonscriptions Députés(es) Etobicoke Centre Allan Rock Etobicoke-Centre Allan Rock Churchill River Rick Laliberte Rivière Churchill Rick Laliberte Prince George—Peace River Jay Hill Prince George—Peace River Jay Hill Rimouski-Neigette-et-la Mitis Suzanne Tremblay Rimouski-Neigette-et-la Mitis Suzanne Tremblay LaSalle—Émard Paul Martin LaSalle—Émard Paul Martin Prince Albert Brian Fitzpatrick Prince Albert Brian Fitzpatrick Charleswood St. James— John Harvard Charleswood St. James— John Harvard Assiniboia Assiniboia Charlevoix Gérard Asselin Charlevoix Gérard Asselin Acadie—Bathurst Yvon Godin Acadie—Bathurst Yvon Godin Cariboo—Chilcotin Philip Mayfield Cariboo—Chilcotin Philip Mayfield Vancouver Island North John Duncan Île de Vancouver-Nord John Duncan Macleod Grant Hill Macleod Grant Hill Beaches—East York Maria Minna Beaches—East York Maria Minna Calgary West Rob Anders Calgary-Ouest Rob Anders Sydney—Victoria Mark Eyking Sydney—Victoria Mark Eyking Souris—Moose Mountain Roy H. -

Wednesday, April 16, 1997

CANADA VOLUME 134 S NUMBER 157 S 2nd SESSION S 35th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Wednesday, April 16, 1997 Speaker: The Honourable Gilbert Parent CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) The House of Commons Debates are also available on the Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 9793 HOUSE OF COMMONS Wednesday, April 16, 1997 The House met at 2 p.m. At the signing of a Canada-Saskatchewan social housing agree- ment, the minister stated that having a single level of government _______________ in charge of administering social housing would maximize the use of taxpayers’ money by simplifying existing arrangements and Prayers encouraging the development of a single window concept. _______________ When will we see powers transferred to the provinces in areas like forestry, tourism and mining? After three and a half years, it is The Speaker: As is our practice on Wednesdays, we will now time this government recognized that the Bloc Quebecois was right sing O Canada. We will be led by the hon. member for Calgary about the need to eliminate overlap. North. * * * _____________________________________________ D (1405) STATEMENTS BY MEMBERS [English] HUMAN RIGHTS [English] Mr. Keith Martin (Esquimalt—Juan de Fuca, Ref.): Mr. NATIONAL VOLUNTEER WEEK Speaker, China is repeatedly jailing dissidents like Wei Jingsheng and student leader Wang Dan for speaking out on human rights. It Mr. George Proud (Hillsborough, Lib.): Mr. Speaker, this has violated its joint declaration agreement on Hong Kong and its week is National Volunteer Week and communities across the basic law by appointing its own legislative council, introducing country will pay tribute to their volunteers and the countless ways laws on subversion and rolling back Hong Kong’s bill of rights. -

Friday, May 28, 1999

CANADA VOLUME 135 S NUMBER 233 S 1st SESSION S 36th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, May 28, 1999 Speaker: The Honourable Gilbert Parent CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) All parliamentary publications are available on the ``Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire'' at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 15429 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, May 28, 1999 The House met at 10 a.m. named department or agency and the said motion shall be deemed adopted when called on ‘‘Motions’’ on the last sitting day prior to May 31; _______________ It is evident from the text I have just quoted that there are no provisions in the standing orders to allow anyone other than the Leader of the Opposition to propose this extension. Prayers D (1005 ) _______________ Furthermore, the standing order does not require that such a motion be proposed. The text is merely permissive. D (1000) I must acknowledge the ingenuity of the hon. member for POINTS OF ORDER Pictou—Antigonish—Guysborough in suggesting that an analo- gous situation exists in citation 924 of Beauchesne’s sixth edition ESTIMATES—SPEAKER’S RULING which discusses the division of allotted days among opposition parties. However, I must agree with the hon. government House leader when he concludes, on the issue of extension, that the The Acting Speaker (Mr. McClelland): Before we begin the standing orders leave the Speaker no discretionary power at all. day’s proceedings I would like to rule on the point of order raised Thus, I cannot grant the hon. member’s request to allow his motion by the hon. -

Computational Identification of Ideology In

Computational Identification of Ideology in Text: A Study of Canadian Parliamentary Debates Yaroslav Riabinin Dept. of Computer Science, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON M5S 3G4, Canada February 23, 2009 In this study, we explore the task of classifying members of the 36th Cana- dian Parliament by ideology, which we approximate using party mem- bership. Earlier work has been done on data from the U.S. Congress by applying a popular supervised learning algorithm (Support Vector Ma- chines) to classify Senatorial speech, but the results were mediocre unless certain limiting assumptions were made. We adopt a similar approach and achieve good accuracy — up to 98% — without making the same as- sumptions. Our findings show that it is possible to use a bag-of-words model to distinguish members of opposing ideological classes based on English transcripts of their debates in the Canadian House of Commons. 1 Introduction Internet technology has empowered users to publish their own material on the web, allowing them to make the transition from readers to authors. For example, people are becoming increasingly accustomed to voicing their opinions regarding various prod- ucts and services on websites like Epinions.com and Amazon.com. Moreover, other users appear to be searching for these reviews and incorporating the information they acquire into their decision-making process during a purchase. This indicates that mod- 1 ern consumers are interested in more than just the facts — they want to know how other customers feel about the product, which is something that companies and manu- facturers cannot, or will not, provide on their own. -

The New Democratic Party and Press Access: Openings and Barriers for Social Democratic Messages

THE NEW DEMOCRATIC PARTY AND PRESS ACCESS: OPENINGS AND BARRIERS FOR SOCIAL DEMOCRATIC MESSAGES by Ian Edward Ross Bachelor of Arts, University of Western Ontario, 2000 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the School of Communication O Ian Ross 2003 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY September 2003 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL NAME: Ian Ross DEGREE: MA TITLE OF THE NEW DEMOCRATIC PARTY AND PRESS EXTENDED ESSAY: ACCESS: OPENINGS AND BARRIERS FOR SOCIAL DEMOCRATIC MESSAGES EXAMINING COMMITTEE: CHAIR: Prof. Gary McCarron Prof. Robert Hackett Senior Supervisor, School of Communication, SFU - Prof. Catherine Murray Supervisor, School of Communication, SFU Prof. Kenne y Stewart Examiner, B Assistant Professor in the Masters of Public Policy Program at SFU Date: p 2-00? PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my wriien permission.