Electronic Dance Music: from Deviant Subculture to Culture Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stephan Heblich Stephen J. Redding Daniel M. Sturm

THE MAKING OF THE MODERN METROPOLIS: EVIDENCE FROM LONDON∗ Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/qje/article/135/4/2059/5831735 by Princeton University user on 21 August 2020 STEPHAN HEBLICH STEPHEN J. REDDING DANIEL M. STURM Using newly constructed spatially disaggregated data for London from 1801 to 1921, we show that the invention of the steam railway led to the first large-scale separation of workplace and residence. We show that a class of quantitative urban models is remarkably successful in explaining this reorganization of economic ac- tivity. We structurally estimate one of the models in this class and find substantial agglomeration forces in both production and residence. In counterfactuals, we find that removing the whole railway network reduces the population and the value of land and buildings in London by up to 51.5% and 53.3% respectively, and decreases net commuting into the historical center of London by more than 300,000 workers. JEL Codes: O18, R12, R40 I. INTRODUCTION Modern metropolitan areas include vast concentrations of economic activity, with Greater London and New York City today ∗We are grateful to the University of Bristol, the London School of Economics, Princeton University, and the University of Toronto for research support. Heblich also acknowledges support from the Institute for New Economic Thinking (INET) Grant no. INO15-00025. We thank the editor, four anonymous referees, Victor Cou- ture, Jonathan Dingel, Ed Glaeser, Vernon Henderson, Petra Moser, Leah Platt Boustan, Will Strange, Claudia Steinwender, Matt Turner, Jerry White, Christian Wolmar, and conference and seminar participants at Berkeley, Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (CIFAR), Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR), Columbia, Dartmouth, EIEF Rome, European Economic Association, Fed Board, Geneva, German Economic Association, Harvard, IDC Herzliya, LSE, Marseille, MIT, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), Nottingham, Princeton, Singapore, St. -

Sexuality, Spirituality and the 'Song of Songs'

setup 10-31-05-web 10/20/05 11:39 AM Page 8 October 31, 2005 America Vol. 193 No. 13, Whole No. 4709 Sexuality, Spirituality and the ‘Song of Songs’ – BY CHRISTOPHER PRAMUK – Only through the body does the way, the ascent to the life of blessedness, lie open to us. — St. Bernard of Clairvaux, Sermons on the Song of Songs HE SONG OF SONGS has long held a privileged place in the mystical theolo- gy and monastic tradition of the church. Commentary on this erotically charged, enigmatic love poetry of the Bible runs like a thread from Origen (d. 254) through St. Bernard (d. 1153) and up to St. John of the Cross (d. T1591). In more contemporary figures, too, like the Trappist monk and spiritual writer Thomas Merton, we find the song like a shimmering veil between the lines of his PHOTO BY TATYANA BORODINA CHRISTOPHER PRAMUK, the author of Surviving the Search: Sexuality, Spirituality and Love (Living the Good News, 1998), lives with his wife and two children in South Bend, Ind. 8 America October 31, 2005 setup 10-31-05-web 10/20/05 11:39 AM Page 9 poems and prayers. The regular reader of Merton expects composed over a period of 18 years—is rightly revered as the to find even in his prose spontaneous, canticle-like verses of masterpiece of medieval monastic literature. Like many others praise, or the dream-like yearning for “one whom my heart before and after him, Bernard saw the song as a sublime alle- loves.” gory on the love of God that can be experienced through con- It is natural to wonder why the Song of Songs has exert- templation. -

Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--History History 2016 Minding the Gap: Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945 Danielle K. Dodson University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: http://dx.doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2016.339 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Dodson, Danielle K., "Minding the Gap: Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945" (2016). Theses and Dissertations--History. 40. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/history_etds/40 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the History at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--History by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

1 Douglas Kellner [

Douglas Kellner [http://www.gseis.ucla.edu/faculty/kellner/] T.W. Adorno and the Dialectics of Mass Culture While T.W. Adorno is a lively figure on the contemporary cultural scene, his thought in many ways cuts across the grain of emerging postmodern orthodoxies. Although Adorno anticipated many post-structuralist critiques of the subject, philosophy, and intellectual practice, his work clashes with the postmodern celebration of media culture, attacks on modernism as obsolete and elitist, and the more affirmative attitude toward contemporary culture and society found in many, but not all, postmodern circles. Adorno is thus a highly contradictory figure in the present constellation, anticipating some advanced tendencies of contemporary thought, while standing firming against other regnant intellectual attitudes and positions. In this article, I argue that Adorno's analyses of the functions of mass culture and communications in contemporary societies constitute valuable, albeit controversial, legacies. Adorno excelled both as a critic of so-called "high culture" and "mass culture," while producing many important texts in these areas. His work is distinguished by the close connection between social theory and cultural critique, and by his ability to contextualize culture within social developments, while providing sharp critical analysis. Accordingly, I discuss Adorno's analysis of the dialectics of mass culture, focusing on his critique of popular music, the culture industry, and consumer culture. I argue that Adorno's critique of mass culture is best read and understood in the context of his work with information superhighway. In conclusion, I offer alternative perspectives on mass communication and culture, and some criticisms of Adorno's position. -

Understanding the Value of Arts & Culture | the AHRC Cultural Value

Understanding the value of arts & culture The AHRC Cultural Value Project Geoffrey Crossick & Patrycja Kaszynska 2 Understanding the value of arts & culture The AHRC Cultural Value Project Geoffrey Crossick & Patrycja Kaszynska THE AHRC CULTURAL VALUE PROJECT CONTENTS Foreword 3 4. The engaged citizen: civic agency 58 & civic engagement Executive summary 6 Preconditions for political engagement 59 Civic space and civic engagement: three case studies 61 Part 1 Introduction Creative challenge: cultural industries, digging 63 and climate change 1. Rethinking the terms of the cultural 12 Culture, conflict and post-conflict: 66 value debate a double-edged sword? The Cultural Value Project 12 Culture and art: a brief intellectual history 14 5. Communities, Regeneration and Space 71 Cultural policy and the many lives of cultural value 16 Place, identity and public art 71 Beyond dichotomies: the view from 19 Urban regeneration 74 Cultural Value Project awards Creative places, creative quarters 77 Prioritising experience and methodological diversity 21 Community arts 81 Coda: arts, culture and rural communities 83 2. Cross-cutting themes 25 Modes of cultural engagement 25 6. Economy: impact, innovation and ecology 86 Arts and culture in an unequal society 29 The economic benefits of what? 87 Digital transformations 34 Ways of counting 89 Wellbeing and capabilities 37 Agglomeration and attractiveness 91 The innovation economy 92 Part 2 Components of Cultural Value Ecologies of culture 95 3. The reflective individual 42 7. Health, ageing and wellbeing 100 Cultural engagement and the self 43 Therapeutic, clinical and environmental 101 Case study: arts, culture and the criminal 47 interventions justice system Community-based arts and health 104 Cultural engagement and the other 49 Longer-term health benefits and subjective 106 Case study: professional and informal carers 51 wellbeing Culture and international influence 54 Ageing and dementia 108 Two cultures? 110 8. -

Razorcake Issue #82 As A

RIP THIS PAGE OUT WHO WE ARE... Razorcake exists because of you. Whether you contributed If you wish to donate through the mail, any content that was printed in this issue, placed an ad, or are a reader: without your involvement, this magazine would not exist. We are a please rip this page out and send it to: community that defi es geographical boundaries or easy answers. Much Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. of what you will fi nd here is open to interpretation, and that’s how we PO Box 42129 like it. Los Angeles, CA 90042 In mainstream culture the bottom line is profi t. In DIY punk the NAME: bottom line is a personal decision. We operate in an economy of favors amongst ethical, life-long enthusiasts. And we’re fucking serious about it. Profi tless and proud. ADDRESS: Th ere’s nothing more laughable than the general public’s perception of punk. Endlessly misrepresented and misunderstood. Exploited and patronized. Let the squares worry about “fi tting in.” We know who we are. Within these pages you’ll fi nd unwavering beliefs rooted in a EMAIL: culture that values growth and exploration over tired predictability. Th ere is a rumbling dissonance reverberating within the inner DONATION walls of our collective skull. Th ank you for contributing to it. AMOUNT: Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc., a California not-for-profit corporation, is registered as a charitable organization with the State of California’s COMPUTER STUFF: Secretary of State, and has been granted official tax exempt status (section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code) from the United razorcake.org/donate States IRS. -

Chiptuning Intellectual Property: Digital Culture Between Creative Commons and Moral Economy

Chiptuning Intellectual Property: Digital Culture Between Creative Commons and Moral Economy Martin J. Zeilinger York University, Canada [email protected] Abstract This essay considers how chipmusic, a fairly recent form of alternative electronic music, deals with the impact of contemporary intellectual property regimes on creative practices. I survey chipmusicians’ reusing of technology and content invoking the era of 8-bit video games, and highlight points of contention between critical perspectives embodied in this art form and intellectual property policy. Exploring current chipmusic dissemination strategies, I contrast the art form’s links to appropriation-based creative techniques and the ‘demoscene’ amateur hacking culture of the 1980s with the chiptune community’s currently prevailing reliance on Creative Commons licenses for regulating access. Questioning whether consideration of this alternative licensing scheme can adequately describe shared cultural norms and values that motivate chiptune practices, I conclude by offering the concept of a moral economy of appropriation-based creative techniques as a new framework for understanding digital creative practices that resist conventional intellectual property policy both in form and in content. Keywords: Chipmusic, Creative Commons, Moral Economy, Intellectual Property, Demoscene Introduction The chipmusic community, like many other born-digital creative communities, has a rich tradition of embracing and encouraged open access, collaboration, and sharing. It does not like to operate according to the logic of informational capital and the restrictive enclosure movements this logic engenders. The creation of chipmusic, a form of electronic music based on the repurposing of outdated sound chip technology found in video gaming devices and old home computers, centrally involves the reworking of proprietary cultural materials. -

The Effects of Background Music on Video Game Play Performance, Behavior and Experience in Extraverts and Introverts

THE EFFECTS OF BACKGROUND MUSIC ON VIDEO GAME PLAY PERFORMANCE, BEHAVIOR AND EXPERIENCE IN EXTRAVERTS AND INTROVERTS A Thesis Presented to The Academic Faculty By Laura Levy In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Psychology in the School of Psychology Georgia Institute of Technology December 2015 Copyright © Laura Levy 2015 THE EFFECTS OF BACKGROUND MUSIC ON VIDEO GAME PLAY PERFORMANCE, BEHAVIOR, AND EXPERIENCE IN EXTRAVERTS AND INTROVERTS Approved by: Dr. Richard Catrambone Advisor School of Psychology Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Bruce Walker School of Psychology Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Maribeth Coleman Institute for People and Technology Georgia Institute of Technology Date Approved: 17 July 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank the researchers and students that made Food for Thought possible as the wonderful research tool it is today. Special thanks to Rob Solomon, whose efforts to make the game function specifically for this project made it a success. Additionally, many thanks to Rob Skipworth, whose audio engineering expertise made the soundtrack of this study sound beautifully. I express appreciation to the Interactive Media Technology Center (IMTC) for the support of this research, and to my committee for their guidance in making it possible. Finally, I wish to express gratitude to my family for their constant support and quiet bemusement for my seemingly never-ending tenure in graduate school. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii LIST OF TABLES vii LIST OF -

Videogame Music: Chiptunes Byte Back?

Videogame Music: chiptunes byte back? Grethe Mitchell Andrew Clarke University of East London Unaffiliated Researcher and Institute of Education 78 West Kensington Court, University of East London, Docklands Campus Edith Villas, 4-6 University Way, London E16 2RD London W14 9AB [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Musicians and sonic artists who use videogames as their This paper will explore the sonic subcultures of videogame medium or raw material have, however, received art and videogame-related fan art. It will look at the work of comparatively little interest. This mirrors the situation in art videogame musicians – not those producing the music for as a whole where sonic artists are similarly neglected and commercial games – but artists and hobbyists who produce the emphasis is likewise on the visual art/artists.1 music by hacking and reprogramming videogame hardware, or by sampling in-game sound effects and music for use in It was curious to us that most (if not all) of the writing their own compositions. It will discuss the motivations and about videogame art had ignored videogame music - methodologies behind some of this work. It will explore the especially given the overlap between the two communities tools that are used and the communities that have grown up of artists and the parallels between them. For example, two around these tools. It will also examine differences between of the major videogame artists – Tobias Bernstrup and Cory the videogame music community and those which exist Archangel – have both produced music in addition to their around other videogame-related practices such as modding gallery-oriented work, but this area of their activity has or machinima. -

Roots Radical – Place, Power and Practice in Punk Entrepreneurship Sarah Louise Drakopoulou Dodd

Roots radical – Place, power and practice in punk entrepreneurship Sarah Louise Drakopoulou Dodd The significance continues to grow of scholarship that embraces critical and contextualized entrepreneurship, seeking rich explorations of diverse entrepreneurship contexts. Following these influences, this study explores the potentialized context of punk entrepreneurship. The Punk Rock band Rancid has a 20-year history of successfully creating independent musical and related creative enterprises from the margins of the music industry. The study draws on artefacts, interviews and videos created by and around Rancid to identify and analyse this example of marginal, alternative entrepreneurship. A three-part analytic frame was applied to analysing these artefacts. Place is critical to Rancid’s enterprise, grounding the band socially, culturally, geographically and politically. Practice also plays an important role with Rancid’s activities encompassing labour, making music, movement and human interactions. The third, and most prevalent, dimension of alterity is that of power which includes data related to dominance, subordination, exclusion, control and liberation. Rancid’s entrepreneurial story is depicted as cycles, not just a linear journey, but following more complicated paths – from periphery to centre, and back again; returning to roots, whilst trying to move forwards too; grounded in tradition but also radically focused on dramatic change. Paradox, hybridized practices, and the significance of marginal place as a rich resource also emerged from the study. Keywords: entrepreneurship; social construction; punk rock; paradox; marginality; periphery Special thanks are due to all the punks and skins who have engaged with my reading of the Rancid story, and given me so much support and feedback along the way, especially Rancid’s drummer, Branden Steineckert, Jesse from Machete Manufacturing, Kostis, Tassos (Rancid Punx Athens Crew) and Panayiotis. -

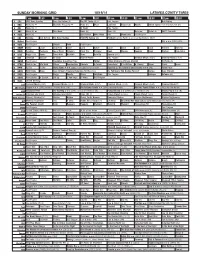

Sunday Morning Grid 10/19/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/19/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Paid Program Bull Riding 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Meet LazyTown Poppy Cat Noodle Action Sports From Brooklyn, N.Y. (N) 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Vista L.A. ABC7 Presents 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Carolina Panthers at Green Bay Packers. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program I.Q. ››› (1994) (PG) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Cooking Cook Kitchen Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Cold. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Special (TVG) 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Home Alone 4 ›› (2002, Comedia) French Stewart. -

The Psytrance Party

THE PSYTRANCE PARTY C. DE LEDESMA M.Phil. 2011 THE PSYTRANCE PARTY CHARLES DE LEDESMA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the School of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of East London for the degree of Master of Philosophy August 2011 Abstract In my study, I explore a specific kind of Electronic Dance Music (EDM) event - the psytrance party to highlight the importance of social connectivity and the generation of a modern form of communitas (Turner, 1969, 1982). Since the early 90s psytrance, and a related earlier style, Goa trance, have been understood as hedonist music cultures where participants seek to get into a trance-like state through all night dancing and psychedelic drugs consumption. Authors (Cole and Hannan, 1997; D’Andrea, 2007; Partridge, 2004; St John 2010a and 2010b; Saldanha, 2007) conflate this electronic dance music with spirituality and indigene rituals. In addition, they locate psytrance in a neo-psychedelic countercultural continuum with roots stretching back to the 1960s. Others locate the trance party events, driven by fast, hypnotic, beat-driven, largely instrumental music, as post sub cultural and neo-tribal, representing symbolic resistance to capitalism and neo liberalism. My study is in partial agreement with these readings when applied to genre history, but questions their validity for contemporary practice. The data I collected at and around the 2008 Offworld festival demonstrates that participants found the psytrance experience enjoyable and enriching, despite an apparent lack of overt euphoria, spectacular transgression, or sustained hedonism. I suggest that my work adds to an existing body of literature on psytrance in its exploration of a dance music event as a liminal space, redolent with communitas, but one too which foregrounds mundane features, such as socialising and pleasure.