On the General Circulation of the Atmosphere Around Colombia Doi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Urban Climate in Urban Design How Land Use Patterns and Building Types Influence the Urban Comfort

Urban climate in urban design How land use patterns and building types influence the urban comfort ABSTRACT This paper will argue the importance of Another factor that is often neglected is consider urban climate in the urban the land use pattern -morphology- that spatial quality, improving urban comfort creates the public space. Basically in the public spaces. The main topics there are three main land use patterns taken into consideration were the land in Medellin, Colombia, that influence use patterns and the building types. the character of the public spaces they The role of the architect here takes are: importance in the way to get a sustaintable future. i) Traditional: Courtyard houses ("Indian" laws) ii) Planned: Rowhouses (modern INTRODUCTION pattern) iii)lnformal invasion of land by squat The climatic behavior in any urban ters (transit step). space depends on many factors such as surrounding vegetation, During the architectural design process, the urban furniture -lamps, and benches. building's orientation and the size of roads Traffic signals, small commercial sites, should be taken into account, but most of the time the street orientation is not considered. etc- , the orientation of the space, other There are very wonderful examples in this climatic conditions such as solar radia- matter in traditional architecture, in Mompox, tion and wind direction and speed. located in Magdalena river bank, with hot and Also the shape of the buildings, their humid climate, where the orientation of the height, materials and the width of the streets give the public space very efficient street. climatic conditions all day round. Arquinotas. -

Colombia Climate Risk Country Profile

Climate Risk and Adaptation Country Profile April 2011 Key to Map Symbols Capital N !( City Barranquilla Roads Santa Marta !( !( River Valledupar Cartagena !( !( Lake Elevation Sincelejo !( Value High : 7088 Monteria !( Low : -416 Terrestrial Biomes !(Cucuta Tropical Broadleaf Forest Tropical Savanna Rio Magdalena !( Rio Atrato Bucaramanga Medellin !( Manizales Rio Tomo !( Rio Meta Pereira !( Bogota !( !( Rio Vichada Armenia Ibague !( Villavicencio !( Cali !( Neiva Rio Guaviare Rio Inirida !( Pasto Rio Vaupes Rio Apaporis Rio Caqueta 0 125 250 500 Kilometers Vulnerability, Risk Reduction, and Adaptation to CLIMATE Climate Change DISASTER RISK ADAPTATION REDUCTION COLOMBIA Climate Change Team ENV Climate Risk and Adaptation Country Profile Colombia COUNTRY OVERVIEW Colombia encompasses an area of more than 1.1 million square kilometers and is the only country in South America with both a Caribbean and Pacific coastline. With an estimated population of 44.5 million, Colombia is the third most populous country in Latin America.1 Even though Colombia is ranked 77th in the Human Development Index and has an upper middle-income country status and annual GDP of 234 billion USD2, it has one of the highest levels of inequality in the world – 52.6 percent of the total population live below the poverty line and this figure reaches 69 percent in rural areas.3 Colombia has one of the highest rates of internally displaced people (IDP) in the world due to civil conflicts, leaving as many as 3.7 million especially vulnerable to climate change.4 Key Sectors The majority of the population resides in two areas: the elevated Andes, where water shortages and land degradation already pose a threat, and the coastal and Agriculture and Livestock insular areas, where the expected increase in sea level and floods will affect human Water Resources settlements and economic activities. -

Mari Leland Wayzata High School Medina, MN Colombia, Factor 5: Climate Volatility

1 Mari Leland Wayzata High School Medina, MN Colombia, Factor 5: Climate Volatility Colombia: Feeding the Future and Sustaining Safe Water Despite Climate Change In the past, Colombia’s agriculture was blocked by guerrilla violence, rural displacement, and dangerous narcotic businesses. Now that Colombia has worked past those problems and established itself as a Presidential Republic (The World Factbook), a new, bigger, and more indiscriminate barrier is blocking their way: climate volatility. With a diverse geography, Colombia faces different risks throughout. But with increasing political stability, and a new drive to safeguard against a changing climate; water safety and agricultural production can be sustainable. With a population nearing 50 million (The World Factbook), Colombia is the third most populous country in Latin America (Penarredonda). Of its large population, 76.72% of Colombians live in urban settings, leaving around 23.29% to live rurally (Colombia - Urban Population). Recent years in Colombia have seen rapid urbanization, but with the end of corrupt political instability and rural isolation caused by internal conflict, it is likely more Colombians will migrate back to rural areas and farm again (Ama). Rural farming in Colombia is important; the economy has a large base in agricultural exports and overall, 37.5% of land is used for agricultural production (The World Factbook). High-value crops for Colombia include, but are not limited too, tropical fruit, coffee, and cocoa (Daniels). Not only are these crops important to Colombia, but to the world. As the world’s second-largest coffee grower, Colombia produces 13-16% of the global coffee supply and is also the worlds third largest banana exporter (Colombia - Agriculture). -

Mining-Induced Displacement and Resettlement in Colombia

Mining-induced displacement and resettlement in Colombia Socio-economic and cultural consequences of resettlements of campesinos and indigenous people - The case of the Cerrejón open pit mine in La Guajira Masterarbeit vorgelegt von Benedikt Hora bei Univ. Prof. Dr. Martin Coy Universität Innsbruck August 2014 Masterarbeit Mining-induced displacement and resettlement in Colombia Socio-economic and cultural consequences of resettlements of campesinos and indigenous people – The case of the Cerrejón open pit mine in La Guajira Verfasser Benedikt Hora B.Sc. Angestrebter akademischer Grad Master of Science (M.Sc.) eingereicht bei Herrn Univ. Prof. Dr. Martin Coy Institut für Geographie Fakultät für Geo- und Atmosphärenwissenschaften an der Leopold-Franzens-Universität Innsbruck Eidesstattliche Erklärung Ich erkläre hiermit an Eides statt durch meine eigenhändige Unterschrift, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbstständig verfasst und keine anderen als die angegebene Quellen und Hilfsmittel verwendet habe. Alle Stellen, die wörtlich oder inhaltlich an den angegebenen Quellen entnommen wurde, sind als solche kenntlich gemacht. Die vorliegende Arbeit wurde bisher in gleicher oder ähnlicher Form noch nicht als Magister- /Master-/Diplomarbeit/Dissertation eingereicht. _______________________________ Innsbruck, August 2014 Unterschrift Contents CONTENTS Contents ................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Preface -

Technical Summary the Overall Objective of This Regional Project Is

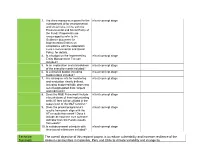

3. Are there measures in place for the n/a at concept stage management of for environmental and social risks, in line with the Environmental and Social Policy of the Fund? Proponents are encouraged to refer to the Guidance document for Implementing Entities on compliance with the Adaptation Fund Environmental and Social Policy, for details. 4. Is a budget on the Implementing n/a at concept stage Entity Management Fee use included? 5. Is an explanation and a breakdown n/a at concept stage of the execution costs included? 6. Is a detailed budget including n/a at concept stage budget notes included? 7. Are arrangements for monitoring n/a at concept stage and evaluation clearly defined, including budgeted M&E plans and sex-disaggregated data, targets and indicators? 8. Does the M&E Framework include n/a at concept stage a break-down of how implementing entity IE fees will be utilized in the supervision of the M&E function? 9. Does the project/programme’s n/a at concept stage results framework align with the AF’s results framework? Does it include at least one core outcome indicator from the Fund’s results framework? 10. Is a disbursement schedule with n/a at concept stage time-bound milestones included? Technical The overall objective of this regional project is to reduce vulnerability and increase resilience of the Summary Andean communities in Colombia, Peru and Chile to climate variability and change by 3. Are there measures in place n/a at concept stage for the management of for environmental and social risks, in line with the Environmental and Social Policy of the Fund? Proponents are encouraged to refer to the Guidance document for Implementing Entities on compliance with the Adaptation Fund Environmental and Social Policy, for details. -

Sustainable Low-Carbon Development in Orinoquia Region Project (P160680)

The World Bank Sustainable Low-Carbon Development in Orinoquia region Project (P160680) Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Combined Project Information Documents / Integrated Safeguards Datasheet (PID/ISDS) For Official Use Only Appraisal Stage | Date Prepared/Updated: November 2, 2017 | Report No: PIDISDSA21196 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Nov 2, 2017 Page 1 of 35 The World Bank Sustainable Low-Carbon Development in Orinoquia region Project (P160680) BASIC INFORMATION OPS_TABLE_BASIC_DATA A. Basic Project Data Country Project ID Project Name Parent Project ID (if any) Colombia P160680 Sustainable Low-Carbon Development in Orinoquia region Project Region Estimated Appraisal Date Estimated Board Date Practice Area (Lead) LATIN AMERICA AND CARIBBEAN 07-Nov-2017 N/A Environment & Natural Resources Financing Instrument Borrower(s) Implementing Agency GEF Focal Area Investment Project Financing Ministry of Agriculture and Ministry of Agriculture Multi-focal area Rural Development and Rural Development (MADR) (MADR), Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development (MADS), National Planning Department (DNP), Instituto de For Official Use Only Hidrologia, Meteorologia y Estudios Ambientales (IDEAM) Proposed Development Objective(s) To improve enabling conditions for sustainable and low-carbon landscape planning and management in project targeted areas. Components Integrated Land- Use Planning and Improved Governance for Deforestation Control Sustainable Land- Use Management Definition of -

The Lgbti Movement's Spiral Trajectory: from Peace

Global LGBTI Human Rights Partnership THE LGBTI MOVEMENT’S SPIRAL TRAJECTORY: FROM PEACE PROCESSES TO LEGAL AND JURIDICAL GAINS AND BACK AGAIN CREDITS Author: Pascha Bueno-Hansen Researcher Assistant: Melissa Monroy Agámez Contributors: Brenda Salas Neves, Sophie Kreitzberg Proofreader: Sabrina Rich Designer: Six Pony Hitch The Astraea Lesbian Foundation for Justice is the only philanthropic organization working exclusively to advance LGBTQI rights around the globe. We support hundreds of brilliant and brave grantee partners in the U.S. and internationally who challenge oppression and seed social change. We work for racial, economic, social, and gender justice, because we all deserve to live our lives freely, without fear, and with profound dignity. Thank you to the following organizations who contributed to this research: Santamaría Fundación Mujeres al Borde GLEFAS Colombia Diversa Caribe Afirmativo La Plataforma LGBTI por la Paz Corporación Viva la Ciudadanía Planeta Paz Red GPAZ Fondo Lunaria Corporación Viva la Ciudadanía Red Comunitaria Trans Armario Abierto Asociación Jóvenes Benkos Ku Suto Grupo de Acción y Apoyo a Personas Trans Raras y no tan Raras Red de Mujeres Trans del Eje Cafetero Cover photo: Camilo Gómez, Sentiido Pages 5, 11, 15, 37, 43: Felipe Alarcón, Sentiido Pages 27, 47: Sentiido Pages 33: Laura Weinstein, Firma Decreto Trans, Sentiido Copyright © 2020 by Astraea Lesbian Foundation for Justice October 2020 CONTENTS 2 KEY FINDINGS 4 INTRODUCTION 7 TIMELINE 10 MOVEMENT TRAJECTORY 13 MOVEMENT STRATEGIES, WINS, AND CHALLENGES 14 Judicial 20 Political 21 Sociocultural 25 PEACE PROCESS 30 DYNAMICS OF POLITICAL CLOSURE 34 PRIORITIES 38 RECOMMENDATIONS 39 Funders 41 Researchers 42 METHODOLOGY KEY FINDINGS Spiral Trajectory. -

Plan Colombia: Reality of the Colombian Crisis and Implications for Hemispheric Security

PLAN COLOMBIA: REALITY OF THE COLOMBIAN CRISIS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR HEMISPHERIC SECURITY Luz E. Nagle December 2002 ***** The views expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. This report is cleared for public release; distribution is unlimited. ***** The author would like to thank Professor Robert Batey for his valuable insights, critical input, and helpful suggestions during the writing of this monograph. ***** Comments pertaining to this report are invited and should be forwarded to: Director, Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, 122 Forbes Ave., Carlisle, PA 17013-5244. Copies of this report may be obtained from the Publications Office by calling (717) 245-4133, FAX (717) 245-3820, or via the Internet at Rita.Rummel@carlisle. army.mil ***** Most 1993, 1994, and all later Strategic Studies Institute (SSI) monographs are available on the SSI Homepage for electronic dissemination. SSI’s Homepage address is: http://www.carlisle.army. mil/ssi/index.html ***** The Strategic Studies Institute publishes a monthly e-mail newsletter to update the national security community on the research of our analysts, recent and forthcoming publications, and upcoming conferences sponsored by the Institute. Each newsletter also provides a strategic commentary by one of our research analysts. If you are interested in receiving this newsletter, please let us know by e-mail at [email protected] or by calling (717) 245-3133. ISBN 1-58487-109-1 ii FOREWORD As American foreign policy and military asset management expand beyond the so-called “Drug War” in Colombia, Professor Luz Nagle analyzes that country’s problems and makes recommendations regarding what it will take to achieve stated U.S. -

Severe Tornadoes on the Caribbean Coast of Colombia Since 2001 and Their Relation to Local Climate Conditions

Severe tornadoes on the Caribbean coast of Colombia since 2001 and their relation to local climate conditions J. C. Ortiz-Royero & Monica Rosales Natural Hazards Journal of the International Society for the Prevention and Mitigation of Natural Hazards ISSN 0921-030X Nat Hazards DOI 10.1007/s11069-012-0337-8 1 23 Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by Springer Science+Business Media B.V.. This e-offprint is for personal use only and shall not be self- archived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your work, please use the accepted author’s version for posting to your own website or your institution’s repository. You may further deposit the accepted author’s version on a funder’s repository at a funder’s request, provided it is not made publicly available until 12 months after publication. 1 23 Author's personal copy Nat Hazards DOI 10.1007/s11069-012-0337-8 ORIGINAL PAPER Severe tornadoes on the Caribbean coast of Colombia since 2001 and their relation to local climate conditions J. C. Ortiz-Royero • Monica Rosales Received: 11 April 2011 / Accepted: 31 July 2012 Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2012 Abstract Tornadoes have been reported in various places around the world. The United States has the greatest number of tornado reports. In South America, tornadoes have been reported in Argentina and neighboring countries, such as Chile, Brazil, and Uruguay. There are no reports of tornadoes in Colombia in the worldwide databases. The first reported tornado event in Colombia took place in 2001. -

1.1 Colombia Humanitarian Background

1.1 Colombia Humanitarian Background Disasters, Conflicts and Migration Seasonal Effects on Logistics Capacities Capacity and Contacts for In-Country Emergency Response Government Humanitarian Community Disasters, Conflicts and Migration Natural Hazards Type Occurs Comments / Details Drought No Droughts no, but Dry season yes, are common in Colombia during the year, especially, December to March. Earthquakes Yes Colombia is considered a country with a seismic risk, due to its located on the “Ring of Fire - Pacific”, areas of high seismic risk are located in the departments of Nariño, Choco, Caldas and Santander (where the town of “Los Santos” is located which is considered as the second most seismic town of the world). Epidemics Yes The variety of climates and weather phenomena influencing epidemics, especially seasonal influenzas. Other major epidemics that impact the population are HIV / AIDS, Tuberculosis, Malaria, Hepatitis B and C, Dengue, Meningitis. The National Institute of Health (https://www.ins.gov.co/) issues a weekly epidemiological bulletin with epidemics in the country and how to deal with their presence. Extreme No Due to the climatic diversity in Colombia temperatures can be between 30°C on the coast and plains, to the cold Temperatures temperatures 0°C in the mountain peaks of the Andes Mountains and the Sierra Nevada of Santa Marta. Flooding Yes Usually, flooding problems appears during June, August and September. Due to the poor hydric policies, indiscriminate logging, pollution in rivers, construction uncontrolled in flow zones is a additional factor which increases the impact of this phenomenon Insect Yes Cases of transmission: Dengue virus and Chikungunya virus Infestation Mudslides Yes The diversity of soils, topography and climate of Colombia are conditions that make the country one of the most susceptible to this phenomenon. -

Cold Fronts in the Colombian Caribbean Sea and Their Relationship to Extreme Wave Events

Open Access Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 13, 2797–2804, 2013 Natural Hazards www.nat-hazards-earth-syst-sci.net/13/2797/2013/ doi:10.5194/nhess-13-2797-2013 and Earth System © Author(s) 2013. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Sciences Cold fronts in the Colombian Caribbean Sea and their relationship to extreme wave events J. C. Ortiz-Royero1, L. J. Otero1, J. C. Restrepo1, J. Ruiz1, and M. Cadena2 1Applied Physics Group – Ocean and Atmosphere Area – Physics Department, Universidad del Norte, Barranquilla, Colombia 2Meteorology Branch, Instituto de Hidrología, Meteorología y Estudios Ambientales de Colombia (IDEAM), Bogotá D.C., Colombia Correspondence to: J. C. Ortiz-Royero ([email protected]) Received: 3 April 2013 – Published in Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss.: 29 July 2013 Revised: 8 October 2013 – Accepted: 11 October 2013 – Published: 7 November 2013 Abstract. Extreme ocean waves in the Caribbean Sea are the structural collapse of the Puerto Colombia pier, located commonly related to the effects of storms and hurricanes near the city of Barranquilla, between 5 and 10 March 2009. during the months of June through November. The collapse This information is invaluable when evaluating average and of 200 m of the Puerto Colombia pier in March 2009 re- extreme wave regimes for the purpose of informing the de- vealed the effects of meteorological phenomena other than sign of structures in this region of the Caribbean. storms and hurricanes that may be influencing the extreme wave regime in the Colombian Caribbean. The marked sea- sonality of these atmospheric fronts was established by ana- lyzing the meteorological–marine reports of the Instituto de Hidrología, Meteorología y Estudios Ambientales of Colom- 1 Introduction bia (IDEAM, based on its initials in Spanish) and the Centro de Investigación en Oceanografía y Meteorología of Colom- According to Ortiz et al. -

Sea Breeze in the Colombian Caribbean Coast

Atmósfera 31(4), 389-406 (2018) doi: 10.20937/ATM.2018.31.04.06 Sea breeze in the Colombian Caribbean coast Ascario PÉREZ R.1, Juan C. ORTIZ R.1*, Luis F. BEJARANO A.2, Luis OTERO D.1, Juan C. RESTREPO L.1 and Andrés FRANCO H.3 1 Departamento de Física y Geociencias, Universidad del Norte, km 5 Antigua Vía a Puerto Colombia, Barranquilla, Colombia. 2 Physics and Meteorology Department, University of Puerto Rico, PO BOX 9000, Mayagüez, PR 00681-9000. 3 Departamento de Biología, Universidad de Bogotá Jorge Tadeo Lozano, Carrera 4 núm. 22-61, Bogotá, Colombia. * Corresponding author; email: [email protected] Received: March 17, 2017; accepted: August 29, 2018 RESUMEN La circulación de la brisa marina es un sistema de mesoescala bien conocido e importante, impulsado por las diferentes propiedades de recepción y almacenamiento de calor solar entre la tierra y el mar durante un día, y se ha comprobado su efecto en el oleaje, las corrientes y el transporte de contaminantes atmosféricos, entre otros. En este trabajo se realizó la caracterización de la brisa marina en tres zonas costeras del Caribe colombiano al norte de América del Sur: Riohacha, Barranquilla y Santa Marta, mediante el análisis de los datos del Instituto de Hidrología, Meteorología y Estudios Ambientales de Colombia, en el periodo com- prendido entre 1981 y 2008, y con datos de la estación de la Universidad de Bogotá Jorge Tadeo Lozano en la ciudad de Santa Marta en el periodo comprendido entre el 1 de enero y el 31 de diciembre de 2010.