Unit14. Potential Competition Mergers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 MARCH 2020 To Our Shareholders Alex Gorsky Chairman and Chief Executive Officer By just about every measure, Johnson & These are some of the many financial and Johnson’s 133rd year was extraordinary. strategic achievements that were made possible by the commitment of our more than • We delivered strong operational revenue and 132,000 Johnson & Johnson colleagues, who adjusted operational earnings growth* that passionately lead the way in improving the health exceeded the financial performance goals we and well-being of people around the world. set for the Company at the start of 2019. • We again made record investments in research and development (R&D)—more than $11 billion across our Pharmaceutical, Medical Devices Propelled by our people, products, and and Consumer businesses—as we maintained a purpose, we look forward to the future relentless pursuit of innovation to develop vital with great confidence and optimism scientific breakthroughs. as we remain committed to leading • We proudly launched new transformational across the spectrum of healthcare. medicines for untreated and treatment-resistant diseases, while gaining approvals for new uses of many of our medicines already in the market. Through proactive leadership across our enterprise, we navigated a constant surge • We deployed approximately $7 billion, of unique and complex challenges, spanning primarily in transactions that fortify our dynamic global issues, shifting political commitment to digital surgery for a more climates, industry and competitive headwinds, personalized and elevated standard of and an ongoing litigious environment. healthcare, and that enhance our position in consumer skin health. As we have experienced for 133 years, we • And our teams around the world continued can be sure that 2020 will present a new set of working to address pressing public health opportunities and challenges. -

Manufacturers/Wholesalers Street City ST Zip 454 Life Sciences Branford CT A.L.I Holdings, LLC A.L.I

Manufacturers/Wholesalers Street City ST Zip 454 Life Sciences Branford CT A.L.I Holdings, LLC A.L.I. Imaging Systems Corp A.L.I. Technologies (International) LLC Abbott Diabetes Care Division Abbott Diagnostic Division Abbott Laboratories 100 Abbott Park Rd. Bldg. AP6D-1 Abbott Park IL 60064 Abbott Molecular Division Abbott Nutrition Products Division Abbott Pharmaceutical Products Group Abbott Point of Care Division Abbott Vascular Division Abraxis Bioscience, LLC. 11755 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 2000 Los Angeles CA 90025 Access Diabetic Supply, LLC Acclarent, Inc. 1525-B O'Brien Dr. Menlo Park CA 94025 Acorda Therapeutics, Inc. 15 Skyline Drive Hawthorne NY 10532 Advanced Neuromodulation Systems, Inc. Advanced Respiratory, Inc. Advanced Sterilization Products 33 Technology Drive Irvine CA 92618 Aesculap Implant Systems, Inc. 3773 Corporate Parkway Center Valley PA 18034 Aesculap, Inc. 3773 Corporate Parkway Center Valley PA 18034 Alaven Pharmaceuticals, LLC 2260 Northwest parkway Suite A Marietta GA 30067 Alcon Laboratories, Inc. 6201 South Freeway Fort Worth TX 76134 Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Inc. 352 Knotter Drive Cheshire CT 06410 Alkermes, Inc. 88 Sidney Street Cambridge MA 02139 Allen Medical Systems, Inc. Allergan Sales, LLC Allergan USA, Inc. Allergan, Inc. 2525 Dupont Drive Irvine CA 92612 Alpharma Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Alpharma Pharmaceuticals, LLC AMAG Pharmaceuticals, Inc. 100 Hayden Avenue Lexington MA 02421 AMATECH Corporation American Medical Distributors, Inc. 100 New Highway N Amityville NY 11701 American Medical System, -

2020 Annual Report 2020 PARTNER of the YEAR 3 Annual Comparison SUSTAINED, CONSISTENT GROWTH

Greater Together Annual Report 2020 Greater Together The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic led to unprecedented challenges for the global healthcare industry in 2020, and West played a vital role in the race to deliver an effective vaccine for the virus. CUSTOMERS: OUR PARTNERS Through these challenging times, vaccine developers have trusted West as a partner of choice to help protect their sensitive biomolecules. This is a testament to West’s almost 100 years of experience and reputation for leadership in quality. We have met these high expectations through our ability to flex our operations within our global network to meet supply needs. These customers were seeking components to support the development work, clinical trials, and potentially post-approval launches, and we have From the start of this global been committed to scaling production to meet their future volume requests. pandemic, we have had two In addition, West is also supplying primary packaging components for therapeutics used to treat COVID-19, as well as critical components that are priorities: first, ensuring the included in some of the diagnostic kit products that are being used to detect health and safety of our team COVID-19. members; and second, making We are committed to doing our part to provide for the large-scale manufacture of high-quality components required to serve customer needs for the delivery sure our customers have a reliable of a safe, effective COVID-19 vaccine. This has resulted in growing our global supply of the components that workforce to approximately 9,200 team members, expanding facility and equipment resources and shifting to 24/7 operating schedules at several sites are critical to the containment to address the demand for components associated with COVID-19. -

Brief in Opposition to Certiorari ______

No. 19–1451 In the Supreme Court of the United States __________ SANOFI-AVENTIS DEUTSCHLAND, GMBH, PETITIONER v. MYLAN PHARMACEUTICALS INC., RESPONDENT __________ ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FEDERAL CIRCUIT __________ BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI __________ DOUGLAS H. CARSTEN STEFFEN N. JOHNSON Wilson Sonsini Counsel of Record Goodrich & Rosati, P.C. RICHARD TORCZON 12235 El Camino Real ADAM W. BURROWBRIDGE San Diego, CA 92130 Wilson Sonsini (858) 350–2300 Goodrich & Rosati, P.C. 1700 K Street, N.W. Washington, DC 20006 (202) 973–8800 [email protected] Counsel for Respondent QUESTIONS PRESENTED 1. Whether the Federal Circuit correctly conclud- ed that Sanofi, by failing to plead or otherwise raise a nonjurisdictional Appointments Clause challenge that was pleaded and briefed by dozens of other par- ties and was the subject of extensive public commen- tary, in any brief or at any time until a letter filed two months after oral argument in that court, forfeit- ed such a challenge to the underlying Patent Trial & Appeal Board ruling at issue. 2. Whether the Federal Circuit correctly affirmed the Patent Trial and Appeal Board’s fact-bound con- clusion that Sanofi’s patents were obvious because the purported invention—adding a nonionic surfac- tant to impede insulin glargine molecules from ag- gregating during storage—simply applied a known solution to a known insulin problem. ii RELATED PROCEEDINGS The following proceedings are directly related to the case: Mylan Pharms. Inc. v. Sanofi-Aventis Deutschland GMBH, IPR2017-01526 (P.T.A.B.), final written decision entered December 12, 2018. -

2019 Scientific Program Committee All Relationships Are Considered Compensated

2019 Scientific Program Committee All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless otherwise noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution Patents, Stock and Other Travel, Royalties, Other Expert Other Name Employment Leadership Ownership Honoraria Consulting or Advisory Role Speakers' Bureau Research Funding Accommodations, Intellectual Testimony Relationship Interests Expenses Property Monica M. Leap Syntalogic, Syntimmune Abbvie (Inst), Agenus (Inst), Astellas Pharma (Inst), AstraZeneca Bertagnolli Therapeutics (Inst), Baxalta (Inst), Bayer Health (Inst), Breast Cancer Research Foundation (Inst), Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst), Celgene (Inst), Complion (Inst), Eisai (Inst), Exelixis (Inst), Genentech (Inst), GHI Pharma (Inst), Gilead Sciences (Inst), GlaxoSmithKline (Inst), Incyte (Inst), Janssen (Inst), Jazz Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Leidos (Inst), Lexicon (Inst), Lilly (Inst), Matrex (Inst), Mayo Clinic (Inst), Merck (Inst), MGH (Inst), Millenium Pharamceuticals (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Pharmacyclics (Inst), Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Inst), Sagerock Advisors (Inst), Sanofi (Inst), Taiho Pharmaceutical (Inst), Takeda (Inst), Tesaro (Inst), Teva (Inst) Suzanne George Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Blueprint ARIAD (Inst), Bayer (Inst), Blueprint Medicines (Inst), Deciphera UptoDate Bayer Research to Abbvie (I), Allergan (I) Medicines, Deciphera, Lilly (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Pfizer (Inst) Practice Melissa -

Teva and Mylan

Filed by Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. (Commission File No. 001-16174) pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act of 1933 and deemed filed pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Subject Company: Mylan N.V. Commission File No.: 333-199861 Teva and Mylan Combination to Create an Industry-Leading Company, Well Positioned to Transform the Global Generics Space and Create a Unique and Differentiated Business Model, Leveraging on Its Significant Assets and Capabilities in Generics and Specialty May 5, 2015 2 Safe Harbor Statement This communication contains forward-looking statements within the meaning of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995, which are based on management’s current beliefs and expectations and involve a number of assumptions, known and unknown risks and uncertainties that change over time and could cause future results, performance or achievements to differ materially from the results, performance or achievements expressed or implied by such forward-looking statements. These assumptions, known and unknown risks and uncertainties include, but are not limited to, those discussed in our Annual Report on Form 20-F for the year ended December 31, 2014 and in our other filings with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (the “SEC”), and those relating to Mylan’s business, as detailed from time to time in Mylan’s filings with the SEC, which factors are incorporated herein by reference. Forward-looking statements are generally identified by the words “expects,” “anticipates,” “believes,” “intends,” “estimates,” “will,” “would,” “could,” “should,” “may,” “plans” and similar expressions. All statements, other than statements of historical fact, are statements that could be deemed to be forward-looking statements, including statements about the proposed acquisition of Mylan, the financing of the proposed transaction, the expected future performance (including expected results of operations and financial guidance), and the combined company’s future financial condition, operating results, strategy and plans. -

Faculty and Program Committee Disclosures

Faculty and Program Committee Disclosures The following faculty and program committee members have disclosed relevant financial relationships. First Name Last Name Disclosure Founder and President of Bayou Surgical; Research Support from AstraZenica, Momotero-Gene Bryan Burt Thomas D'Amico Consultant with Scanlan Instruments; Speaker with Medtronic Consultant with AstraZeneca, BioNTech, Gritstone, Illumina, Roche; Research Support from Illumina, Varian; Shareholder (excluding diversified mutual funds) with Cibermed, Foresight Max Diehn Diagnostics Nathaniel Evans Proctor and speaker with Intuitive Surgical Consultant with Scanlan international Diego Gonzalez Rivas Research Support from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly and Company, Genentech/Roche, Merck and Company; Consulting fees from AbbVie Pharmaceuticals, ARMO Biosciences, AstraZeneca, Biodesix, Bolt Biotherapeutics, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cybrexa, Eli Lilly and Company, EMD Serrano, Genentech; Board Memeber with Junshi Pharmaceuticals Roy Herbst Wayne Hofstetter Research Support from Johnson and Johnson Consultant with Astra Zeneca, Daiichi-Sankyo, Imugene, Jounce Therapeutics, Merck Serono, Merck Sharpe and Dohme Corp., Michael J. Hennessy Associates, MIL PeerView, ONO Pharma, Paradigm Medical Communications, PER, Pfizer, Seattle Genetics, Zymeworks Inc.; Research Support from Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli LIlly, Genentech/Roche, Merck & Co.; Shareholder (excluding diversified mutual funds) with Rgenix (stock options) Yelena Janjigian Advisor with Merck, Inc; Consultant -

Delivering Exponential Impact

Delivering exponential impact Impact Standardization Programs How the programs work Vizient Impact Standardization • The average term of a program is three years. Programs financially reward members’ • Nine programs require members to sign up for the program, declare the standardization efforts while reducing supplier(s) of their choice and agree to an annual purchase potential for each product variation and improving product category. These programs require aggregate compliance of 75 percent procurement processes on commonly and individual category compliance of 90 percent to earn rebates. They also purchased products. offer one* opt-out category that can be excluded from compliance Since 1996, members have earned measurement and rebate payment for that program. more than $1.5 billion in cash • The Impact Food and Impact NOVAPLUS® Pharmaceutical programs only rebates through the programs. measure compliance at the aggregate level and have no opt-out options. With 11 programs to choose from Participants in these programs who reach 80 percent aggregate compliance and built-in flexibility within each across all categories will be eligible for rebate payment from any eligible program, it’s easy to gain additional category in the program. value beyond price for your • Members have up to six months to standardize. Categories under conversion organization. are excluded from aggregate compliance calculation and are not eligible for rebates during this optional conversion period. • Rebates — averaging 3 to 6 percent of purchases — are distributed -

Biopharmaceutical Capabilities Pharmaceutical Grade Water and Pure Steam at Maximum Uptime

BIOPHARMACEUTICAL BIOPHARMACEUTICAL CAPABILITIES PHARMACEUTICAL GRADE WATER AND PURE STEAM AT MAXIMUM UPTIME. BIOPHARMACEUTICAL BIOPHARM EXPERIENCE THE DEEPEST EXPERIENCE AND THE BROADEST RANGE OF SOLUTIONS. With thousands of water purification systems successfully installed around the world, MECO serves leading pharmaceutical and biotech companies with over 25 million gallons of product water each day. The MECO global portfolio includes the broadest range of engineered products for purified water and WFI. This depth of global experience ensures that we understand the critical nature of maximized uptime for your operations. This is why all of our processes are built around you. Whatever your requirements—from pretreatment through production, storage and distribution, a single unit of any size or a complete integrated installation— MECO answers with the ideal combination of highly experienced engineers, state-of-the-art manufacturing and first-class service. We are relentless about finding the best solution to our customers’ needs. One that offers the highest quality of product while reducing operating “ and “ capital costs. Our entire team, from engineering to manufacturing to service, takes a studied and methodical approach to everything we do. It’s part of our culture and a key component of our DNA. CHET NUNEZ, DIRECTOR OF APPLICATIONS PHARMA AND BIOTECH CUSTOMERS IN GOOD COMPANY. At MECO, we measure ourselves by the quality of the company we keep. And when we say “keep,” we mean long-term partnerships that produce results. Scan our list of customers and you’ll see the world’s leading pharmaceutical and biotech companies, along with their trusted construction engineering firms. We pride ourselves on standards as exacting and meticulous as those required by our customers. -

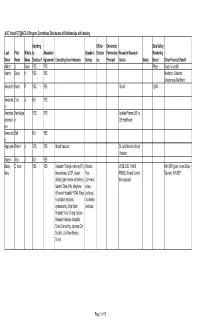

ACC.14 and TCT@ACC-I2 Program Committees Disclosures

ACC.14 and TCT@ACC-i2 Program Committees' Disclosures of Relationships with Industry Anything Officer Ownership Data Safety Last First Middle to Attestation Speaker's Director Partnership Research Research Monitoring Name Name Name Disclose? Agreement Consulting Fees Honoraria Bureau etc. Principal Grants Salary Board Other Financial Benefit Abbott J. Dawn YES YES Pfizer Boston scientific Adams David H. YES YES Medtronic, Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic Alexander Karen P. YES YES Gilead CytRx Amsterda Ezra A. NO YES m Ananthas Karthikeya YES YES Astellas Pharma US Inc , ubramani n GE Healthcare am Anwaruddi Saif NO YES n Applegate Robert J. YES YES Abbott Vascular St Jude Medical, Abbott Vascular Auseon Alex J. NO YES Bairey C. Noel YES YES Research Triangle Institute (RTI) Practice WISE CVD, FAMRI, NIH-SEP (grant review Study Merz Internaltional, UCSF, Kaiser, Pont RWISE, Normal Control, Section), NIH-SEP Gilead (grant review committee), Communic Microvascular Garden State AHA, Allegheny ations HGeneral Hospital, PCNA, Mayo (lectures), Foundation (lectures; Vox Media symposiums), Bryn Mawr (lectures) Hospital, Victor Chang Cardiac Research Institute (Australia, Duke (Consulting, Japense Circ Society , U of New Mexico, Emory Page 1 of 15 Anything Officer Ownership Data Safety Last First Middle to Attestation Speaker's Director Partnership Research Research Monitoring Name Name Name Disclose? Agreement Consulting Fees Honoraria Bureau etc. Principal Grants Salary Board Other Financial Benefit Ballantyne Christie M. YES YES Merck & Company, Pfizer, Abbott Pfizer, Amgen, Takeda, Genentech, Arena, Aegerion, Sanofi-Synthelabo, Novartis, Esperion, Omthera, Amarin, Novartis, Cerenis, Roche, Resverlogix, Genentech, Amarin, Amgen, Sanofi- GlaxoSmithKline, Abbott, Synthelabo, Abbott, Genzyme, Merck & Company, Eli Kowa, Regeneron Lilly, Roche, Regeneron Banerjee Subhash YES YES Covidien Medtronic Mdcare Gilead, Boston Scientific Corporation Global LLC, Corporation HygeaTel Battle Robert W. -

Shareholder Engagement

SHAREHOLDER ENGAGEMENT APRIL 2019 Allergan Cautionary Statements Forward Looking Statements This communication includes statements that refer to estimated or anticipated future events and are forward looking statements. We have based our forward looking statements on management’s beliefs and assumptions based on information available to our management at the time these statements are made. Such forward looking statements reflect our current perspective of our business, future performance, existing trends and information as of the date of this filing. These include, but are not limited to, our beliefs about future revenue and expense levels and growth rates, prospects related to our strategic initiatives and business strategies, including the integration of, and synergies associated with, strategic acquisitions, express or implied assumptions about government regulatory action or inaction, anticipated product approvals and launches, business initiatives and product development activities, assessments related to clinical trial results, product performance and competitive environment, and anticipated financial performance. Without limiting the generality of the foregoing, words such as “may,” “will,” “expect,” “believe,” “anticipate,” “plan,” “intend,” “could,” “would,” “should,” “estimate,” “continue,” or “pursue,” or the negative or other variations thereof or comparable terminology, are intended to identify forward looking statements. The statements are not guarantees of future performance and involve certain risks, uncertainties and assumptions that are difficult to predict. We caution the reader that these statements are based on certain assumptions, risks and uncertainties, many of which are beyond our control. In addition, certain important factors may affect our actual operating results and could cause such results to differ materially from those expressed or implied by forward looking statements. -

3M Company 3M Health Information Systems Abbott Laboratories Inc

Vendor 3M COMPANY 3M HEALTH INFORMATION SYSTEMS ABBOTT LABORATORIES INC. ABBOTT NUTRITION ABBOTT VASCULAR DEVICES ACACIA ACCURAY INC. ACCUTYPE MEDICAL SERVICES ACCUVEIN LLC ACELL INC. ACUSIS LLC ACUTE CARE PHARMACEUTICALS ADROIT MEDICAL SYSTEMS INC ADVANCE MEDICAL DESIGNS INC. ADVANCED MEDICAL INNOVATIONS ADVANCED VASCULAR DYNAMICS ADVANCEPIERRE FOODS INC AEROSCOUT INC AESCULAP IMPLANT SYSTEMS INC. AESCULAP INC. AFFLINK INC. AGAMATRIX INC AGFA HEALTHCARE CORPORATION AIR LIQUIDE HEALTHCARE AIR MD AIRGAS INC. ALADDIN TEMP-RITE ALERE NORTH AMERICA INC. ALL MEDICAL CARE ALLCARE INC. ALLEGION ALLERGAN USA INC ALLIANCE TECH MEDICAL INC. ALLIANT HEALTHCARE ALLIED HEALTHCARE PRODUCTS INC. ALLIQUA BIOMEDICAL ALLSEATING CORPORATION ALPHA MEDICAL DISTRIBUTOR INC AMBLER SURGICAL CORP. AMBU INC. AMD-RITMED INC. AMERICAN CONTRACT SYSTEMS AMERICAN DAWN INC AMERICAN DOCTORS ONLINE LLC AMERICAN MEDICAL DEPOT AMERICAN OFFICE PRODUCTS DISTRIBUTORS AMERICAN SOLUTIONS FOR BUSINESS AMERICAN SURGICAL SPECIALTIES COMPANY AMICO CORPORATION ANCHOR PACKAGING ANDOVER HEALTHCARE INC ANGELICA TEXTILE SERVICES ANGIODYNAMICS INC ANSELL HEALTHCARE PRODUCTS INC APOLLO ENDOSURGERY APOLLO SAFETY APPLIED MEDICAL RESOURCES CORPORATION ARAMARK CLINICAL TECHNOLOGY SERVICES ARAMARK UNIFORM AND CAREER APPAREL ARCHIBALD FROZEN DESSERTS ARJOHUNTLEIGH INC ARKRAY USA ARMSTRONG RELOCATION ARROW INTERNATIONAL INC ARROW-INTECHRA LLC ARTCRAFT PROMOTIONAL CONCEPTS ARUP LABORATORIES ARYZTA LLC ASCOM US INC ASI SYSTEM INTEGRATION INC ASIAN FOOD SOLUTIONS INC ASPEN SURGICAL PRODUCTS INC. ATEECO INC ATLAS VAN LINES INC. ATT MOBILITY NATIONAL ACCOUNTS LLC AUROMEDICS PHARMA LLC AUTHENTIDATE HOLDING CORP AVID MEDICAL INC. B. BRAUN MEDICAL INC. BACTERIN INTERNATIONAL INC BAGCRAFTPAPERCON BARD ACCESS SYSTEM BARD MEDICAL DIVISION BARD PERIPHERAL VASCULAR INC BARILLA AMERICA BARRINGTON VENTURES BAUSCH LOMB SURGICAL INC. BAXTER HEALTHCARE CORPORATION BAYER HEALTHCARE BDI PHARMA BEANITOS INC BEAR FACTS ENTERTAINMENT LLC BEAVER VISITEC INTERNATIONAL INC BECKMAN COULTER INC BECTON DICKINSON AND COMPANY BELIMED INC.