Roald Amundsen”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strategia Del Governo Italiano Per L'artico

ITALY IN THE ARCTIC TOWARDS AN ITALIAN STRATEGY FOR THE ARCTIC NATIONAL GUIDELINES MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS AND INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION 2015 1 ITALY IN THE ARCTIC 1. ITALY IN THE ARCTIC: MORE THAN A CENTURY OF HISTORY The history of the Italian presence in the Arctic dates back to 1899, when Luigi Amedeo di Savoia, Duke of the Abruzzi, sailed from Archangelsk with his ship (christened Stella Polare) to use the Franz Joseph Land as a stepping stone. The plan was to reach the North Pole on sleds pulled by dogs. His expedition missed its target, though it reached previously unattained latitudes. In 1926 Umberto Nobile managed to cross for the first time the Arctic Sea from Europe to Alaska, taking off from Rome together with Roald Amundsen (Norway) and Lincoln Ellsworth (USA) on the Norge airship (designed and piloted by Nobile). They were the first to reach the North Pole, where they dropped the three national flags. 1 Two years later Nobile attempted a new feat on a new airship, called Italia. Operating from Kings Bay (Ny-Ålesund), Italia flew four times over the Pole, surveying unexplored areas for scientific purposes. On its way back, the airship crashed on the ice pack north of the Svalbard Islands and lost nearly half of its crew. 2 The accident was linked to adverse weather, including a high wind blowing from the northern side of the Svalbard Islands to the Franz Joseph Land: this wind stream, previously unknown, was nicknamed Italia, after the expedition that discovered it. 4 Nobile’s expeditions may be considered as the first Italian scientific missions in the Arctic region. -

Arctic Expedition12° 16° 20° 24° 28° 32° Spitsbergen U Svalbard Archipelago 80° 80°

distinguished travel for more than 35 years Voyage UNDER THE Midnight Sun Arctic Expedition12° 16° 20° 24° 28° 32° Spitsbergen u Svalbard Archipelago 80° 80° 80° Raudfjorden Nordaustlandet Woodfjorden Smeerenburg Monaco Glacier The Arctic’s 79° 79° 79° Kongsfjorden Svalbard King’s Glacier Archipelago Ny-Ålesund Spitsbergen Longyearbyen Canada 78° 78° 78° i Greenland tic C rcle rc Sea Camp Millar A U.S. North Pole Russia Bellsund Calypsobyen Svalbard Archipelago Norway Copenhagen Burgerbukta 77° 77° 77° Cruise Itinerary Denmark Air Routing Samarin Glacier Hornsund Barents Sea June 20 to 30, 2022 4° 8° Spitsbergen12° u Samarin16° Glacier20° u Calypsobyen24° 76° 28° 32° 36° 76° Voyage across the Arctic Circle on this unique 11-day Monaco Glacier u Smeerenburg u Ny-Ålesund itinerary featuring a seven-night cruise round trip Copenhagen 1 Depart the U.S. or Canada aboard the Five-Star Le Boréal. Visit during the most 2 Arrive in Copenhagen, Denmark enchanting season, when the region is bathed in the magical 3 Copenhagen/Fly to Longyearbyen, Spitsbergen, light of the Midnight Sun. Cruise the shores of secluded Norway’s Svalbard Archipelago/Embark Le Boréal 4 Hornsund for Burgerbukta/Samarin Glacier Spitsbergen—the jewel of Norway’s rarely visited Svalbard 5 Bellsund for Calypsobyen/Camp Millar archipelago enjoy expert-led Zodiac excursions through 6 Cruising the Arctic Ice Pack sandstone mountain ranges, verdant tundra and awe-inspiring 7 MåkeØyane/Woodfjorden/Monaco Glacier ice formations. See glaciers calve in luminous blues and search 8 Raudfjorden for Smeerenburg for Arctic wildlife, including the “King of the Arctic,” the 9 Ny-Ålesund/Kongsfjorden for King’s Glacier polar bear, whales, walruses and Svalbard reindeer. -

Annual Report COOPERATIVE INSTITUTE for RESEARCH in ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES

2015 Annual Report COOPERATIVE INSTITUTE FOR RESEARCH IN ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES COOPERATIVE INSTITUTE FOR RESEARCH IN ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES 2015 annual report University of Colorado Boulder UCB 216 Boulder, CO 80309-0216 COOPERATIVE INSTITUTE FOR RESEARCH IN ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES University of Colorado Boulder 216 UCB Boulder, CO 80309-0216 303-492-1143 [email protected] http://cires.colorado.edu CIRES Director Waleed Abdalati Annual Report Staff Katy Human, Director of Communications, Editor Susan Lynds and Karin Vergoth, Editing Robin L. Strelow, Designer Agreement No. NA12OAR4320137 Cover photo: Mt. Cook in the Southern Alps, West Coast of New Zealand’s South Island Birgit Hassler, CIRES/NOAA table of contents Executive summary & research highlights 2 project reports 82 From the Director 2 Air Quality in a Changing Climate 83 CIRES: Science in Service to Society 3 Climate Forcing, Feedbacks, and Analysis 86 This is CIRES 6 Earth System Dynamics, Variability, and Change 94 Organization 7 Management and Exploitation of Geophysical Data 105 Council of Fellows 8 Regional Sciences and Applications 115 Governance 9 Scientific Outreach and Education 117 Finance 10 Space Weather Understanding and Prediction 120 Active NOAA Awards 11 Stratospheric Processes and Trends 124 Systems and Prediction Models Development 129 People & Programs 14 CIRES Starts with People 14 Appendices 136 Fellows 15 Table of Contents 136 CIRES Centers 50 Publications by the Numbers 136 Center for Limnology 50 Publications 137 Center for Science and Technology -

Ice Shelf Advance and Retreat Rates Along the Coast of Queen Maud Land, Antarctica K

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 106, NO. C4, PAGES 7097–7106, APRIL 15, 2001 Ice shelf advance and retreat rates along the coast of Queen Maud Land, Antarctica K. T. Kim,1 K. C. Jezek,2 and H. G. Sohn3 Byrd Polar Research Center, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio Abstract. We mapped ice shelf margins along the Queen Maud Land coast, Antarctica, in a study of ice shelf margin variability over time. Our objective was to determine the behavior of ice shelves at similar latitudes but different longitudes relative to ice shelves that are dramatically retreating along the Antarctic Peninsula, possibly in response to changing global climate. We measured coastline positions from 1963 satellite reconnaissance photography and 1997 RADARSAT synthetic aperture radar image data for comparison with coastlines inferred by other researchers who used Landsat data from the mid-1970s. We show that these ice shelves lost ϳ6.8% of their total area between 1963 and 1997. Most of the areal reduction occurred between 1963 and the mid-1970s. Since then, ice margin positions have stabilized or even readvanced. We conclude that these ice shelves are in a near-equilibrium state with the coastal environment. 1. Introduction summer 0Њ isotherm [Tolstikov, 1966, p. 76; King and Turner, 1997, p. 141]. Following Mercer’s hypothesis, we might expect Ice shelves are vast slabs of glacier ice floating on the coastal these ice shelves to be relatively stable at the present time. ocean surrounding Antarctica. They are a continuation of the Following the approach of other investigators [Rott et al., ice sheet and form, in part, as glacier ice flowing from the 1996; Ferrigno et al., 1998; Skvarca et al., 1999], we compare the interior ice sheet spreads across the ocean surface and away position of ice shelf margins and grounding lines derived from from the coast. -

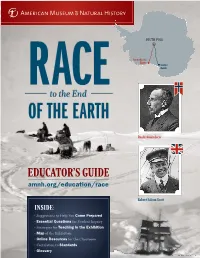

Educator's Guide

SOUTH POLE Amundsen’s Route Scott’s Route Roald Amundsen EDUCATOR’S GUIDE amnh.org/education/race Robert Falcon Scott INSIDE: • Suggestions to Help You Come Prepared • Essential Questions for Student Inquiry • Strategies for Teaching in the Exhibition • Map of the Exhibition • Online Resources for the Classroom • Correlation to Standards • Glossary ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS Who would be fi rst to set foot at the South Pole, Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen or British Naval offi cer Robert Falcon Scott? Tracing their heroic journeys, this exhibition portrays the harsh environment and scientifi c importance of the last continent to be explored. Use the Essential Questions below to connect the exhibition’s themes to your curriculum. What do explorers need to survive during What is Antarctica? Antarctica is Earth’s southernmost continent. About the size of the polar expeditions? United States and Mexico combined, it’s almost entirely covered Exploring Antarc- by a thick ice sheet that gives it the highest average elevation of tica involved great any continent. This ice sheet contains 90% of the world’s land ice, danger and un- which represents 70% of its fresh water. Antarctica is the coldest imaginable physical place on Earth, and an encircling polar ocean current keeps it hardship. Hazards that way. Winds blowing out of the continent’s core can reach included snow over 320 kilometers per hour (200 mph), making it the windiest. blindness, malnu- Since most of Antarctica receives no precipitation at all, it’s also trition, frostbite, the driest place on Earth. Its landforms include high plateaus and crevasses, and active volcanoes. -

Texts G7 Sout Pole Expeditions

READING CLOSELY GRADE 7 UNIT TEXTS AUTHOR DATE PUBLISHER L NOTES Text #1: Robert Falcon Scott and Roald Amundsen (Photo Collages) Scott Polar Research Inst., University of Cambridge - Two collages combine pictures of the British and the Norwegian Various NA NA National Library of Norway expeditions, to support examining and comparing visual details. - Norwegian Polar Institute Text #2: The Last Expedition, Ch. V (Explorers Journal) Robert Falcon Journal entry from 2/2/1911 presents Scott’s almost poetic 1913 Smith Elder 1160L Scott “impressions” early in his trip to the South Pole. Text #3: Roald Amundsen South Pole (Video) Viking River Combines images, maps, text and narration, to present a historical NA Viking River Cruises NA Cruises narrative about Amundsen and the Great Race to the South Pole. Text #4: Scott’s Hut & the Explorer’s Heritage of Antarctica (Website) UNESCO World Google Cultural Website allows students to do a virtual tour of Scott’s Antarctic hut NA NA Wonders Project Institute and its surrounding landscape, and links to other resources. Text #5: To Build a Fire (Short Story) The Century Excerpt from the famous short story describes a man’s desperate Jack London 1908 920L Magazine attempts to build a saving =re after plunging into frigid water. Text #6: The North Pole, Ch. XXI (Historical Narrative) Narrative from the =rst man to reach the North Pole describes the Robert Peary 1910 Frederick A. Stokes 1380L dangers and challenges of Arctic exploration. Text #7: The South Pole, Ch. XII (Historical Narrative) Roald Narrative recounts the days leading up to Amundsen’s triumphant 1912 John Murray 1070L Amundsen arrival at the Pole on 12/14/1911 – and winning the Great Race. -

The South Polar Race Medal

The South Polar Race Medal Created by Danuta Solowiej The way to the South Pole / Sydpolen. Roald Amundsen’s track is in Red and Captain Scott’s track is in Green. The South Polar Race Medal Roald Amundsen and his team reaching the Sydpolen on 14 Desember 1911. (Obverse) Captain R. F. Scott, RN and his team reaching the South Pole on 17 January 1912. (Reverse) Created by Danuta Solowiej Published by Sim Comfort Associates 29 March 2012 Background The 100th anniversary of man’s first attainment of the South Pole recalls a story of two iron-willed explorers committed to their final race for the ultimate prize, which resulted in both triumph and tragedy. In July 1895, the International Geographical Congress met in Lon- don and opened Antarctica’s portal by deciding that the southern- most continent would become the primary focus of new explora- tion. Indeed, Antarctica is the only such land mass in our world where man has ventured and not found man. Up until that time, no one had explored the hinterland of the frozen continent, and even the vast majority of its coastline was still unknown. The meet- ing touched off a flurry of activity, and soon thereafter national expeditions and private ventures started organizing: the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration had begun, and the attainment of the South Pole became the pinnacle of that age. Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen (1872-1928) nurtured at an early age a strong desire to be an explorer in his snowy Norwegian surroundings, and later sailed on an Arctic sealing voyage. -

BOLD ENDEAVORS: BEHAVIORAL LESSONS from POLAR and SPACE EXPLORATION Jack W

BOLD ENDEAVORS: BEHAVIORAL LESSONS FROM POLAR AND SPACE EXPLORATION Jack W. Stuster Anacapa Sciences, Inc., Santa Barbara, CA ABSTRACT Material in this article was drawn from several chapters of the author’s book, Bold Endeavors: Lessons from Polar and Space Anecdotal comparisons frequently are made between Exploration. (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. 1996). expeditions of the past and space missions of the future. the crew gradually became afflicted with a strange and persistent Spacecraft are far more complex than sailing ships, but melancholy. As the weeks blended one into another, the from a psychological perspective, the differences are few condition deepened into depression and then despair. between confinement in a small wooden ship locked in the Eventually, crew members lost almost all motivation and found polar ice cap and confinement in a small high-technology it difficult to concentrate or even to eat. One man weakened and ship hurtling through interplanetary space. This paper died of a heart ailment that Cook believed was caused, at least in discusses some of the behavioral lessons that can be part, by his terror of the darkness. Another crewman became learned from previous expeditions and applied to facilitate obsessed with the notion that others intended to kill him; when human adjustment and performance during future space he slept, he squeezed himself into a small recess in the ship so expeditions of long duration. that he could not easily be found. Yet another man succumbed to hysteria that rendered him temporarily deaf and unable to speak. Additional members of the crew were disturbed in other ways. -

Supplementary File For: Blix A.S. 2016. on Roald Amundsen's Scientific Achievements. Polar Research 35. Correspondence: AAB Bu

Supplementary file for: Blix A.S. 2016. On Roald Amundsen’s scientific achievements. Polar Research 35. Correspondence: AAB Building, Institute of Arctic and Marine Biology, University of Tromsø, NO-9037 Tromsø, Norway. E-mail: [email protected] Selected publications from the Gjøa expedition not cited in the text Geelmuyden H. 1932. Astronomy. The scientific results of the Norwegian Arctic expedition in the Gjøa 1903-1906. Geofysiske Publikasjoner 6(2), 23-27. Graarud A. 1932. Meteorology. The scientific results of the Norwegian Arctic expedition in the Gjøa 1903-1906. Geofysiske Publikasjoner 6(3), 31-131. Graarud A. & Russeltvedt N. 1926. Die Erdmagnetischen Beobachtungen der Gjöa-Expedition 1903- 1906. (Geomagnetic observations of the Gjøa expedition, 1903-06.) The scientific results of the Norwegian Arctic expedition in the Gjøa 1903-1906. Geofysiske Publikasjoner 3(8), 3-14. Holtedahl O. 1912. On some Ordovician fossils from Boothia Felix and King William Land, collected during the Norwegian expedition of the Gjøa, Captain Amundsen, through the North- west Passage. Videnskapsselskapets Skrifter 1, Matematisk–Naturvidenskabelig Klasse 9. Kristiania (Oslo): Jacob Dybwad. Lind J. 1910. Fungi (Micromycetes) collected in Arctic North America (King William Land, King Point and Herschell Isl.) by the Gjöa expedition under Captain Roald Amundsen 1904-1906. Videnskabs-Selskabets Skrifter 1. Mathematisk–Naturvidenskabelig Klasse 9. Christiania (Oslo): Jacob Dybwad. Lynge B. 1921. Lichens from the Gjøa expedition. Videnskabs-Selskabets Skrifter 1. Mathematisk– Naturvidenskabelig Klasse 15. Christiania (Oslo): Jacob Dybwad. Ostenfeld C.H. 1910. Vascular plants collected in Arctic North America (King William Land, King Point and Herschell Isl.) by the Gjöa expedition under Captain Roald Amundsen 1904-1906. -

With Nansen in the North; a Record of the Fram Expedition in 1893-96

with-nXT^sen Ulllii I Hi nil I li "'III"!!!!!!!! Lieut JOHANSi; i*ll III Hi!; :1 III I iiil |i;iii'i'iiiiiiii i; \Ki THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES WITH NANSEN IN THE NORTH [LANCASTER. K lOHANSEN. {Frontis/iiece. WITH NANSEN IN THE NORTH A Record of the Fram Expedition in 1893-96 BY HJALMAR JOHANSEN lieutenant in the norwegian army Translated from the Norwegian BY H. L. BR.EKSTAD LONDON WARD, LOCK AND CO LIMITED NEW YORK AND MELBOURNE 1899 — ijr Contents CHAPTER I TAGE The Equipment of the Expedition— Its Start—The Voyage along the Coast—Farewell to Norway I CHAI'TER II The First Ice — Arrival at Khabarova—Meeting with Trontheim Arrival of the Dogs— Life among the Samoyedes— Christofersen Leaves us—Excursion on Yalmal—The last Human Beings we saw lo CHAPTER III A Heavy Sea—Sverdrup Island—A Reindeer Hunt—The First Bear —A Stiff Pull—Firing with Kerosene 20 CHAPTER IV Death among the Dogs — Taimur Island — Cape Butterless — The Northernmost Point of the Old World—A Walrus Hunt—To the North 28 CHAPTER V Open Water—Unwelcome Guests—Fast in the Ice—Warping—The Northern Lights 34 CHAPTER VI First Day of Rest— Surprised by Bears—The Dogs are let Loose- Ice Pressure—A Hunt in the Dark 4° CHAPTER VII More Bears—The Power of Baking Powder— "Johansen's Friend"— V Electric Light— Shooting Competition ...•• 5° V 1212604 vi COXTENTS CHAPTER VIII PAGE Foot-races on the Ice—More about the Dogs—The Northern Lights- Adulterated Beer—Ice Pressure—Peder Attacked by a Bear . -

Sverdrup-Among-The-Tundra-People

AMONG THE TUNDRA PEOPLE by HARALD U. SVERDRUP TRANSLATED BY MOLLY SVERDRUP 1939 Copyright @ 1978 by Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, elec- tronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the regents. Distributed by : Scripps Institution of Oceanography A-007 University of California, San Diego La Jolla, California 92093 Library of Congress # 78-60483 ISBN # 0-89626-004-6 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We are indebted to Molly Sverdrup (Mrs. Leif J.) for this translation of Hos Tundra-Folket published by Gyldendal Norsk Forlag, Oslo, 1938. We are also indebted to the late Helen Raitt for recovering the manuscript from the archives of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. The Norwegian Polar Institute loaned negatives from Sverdrup's travels among the Chukchi, for figures 1 through 4. Sverdrup's map of his route in the Chukchi country in 19 19/20 was copied from Hos Tundra-Folket. The map of the Chukchi National Okrug was prepared by Fred Crowe, based on the American Geographic Society's Map of the Arctic Region (1975). The map of Siberia was copied from Terence Armstrong's Russian Settlement in the North (1 965) with permission of the Cambridge University Press. Sam Hinton drew the picture of a reindeer on the cover. Martin W. Johnson identified individuals in some of the photographs. Marston C Sargent Elizabeth N. Shor Kittie C C Kuhns Editors The following individuals, most of whom were closely associated with Sverdrup, out of respect for him and wishing to assure preservation of this unusual account, met part of the cost of publication. -

MS ROALD AMUNDSEN Voyage Handbook

MS ROALD AMUNDSEN voyage handbook MS ROALD AMUNDSEN VOYAGE HANDBOOK 20192020 1 Dear Adventurer 2 Dear adventurer, Europe 4 Congratulations on booking make your voyage even more an extraordinary cruise on enjoyable. Norway 6 board our extraordinary new vessel, MS Roald Amundsen. This handbook includes in- formation on your chosen Svalbard 8 The ship’s namesake, Norwe- destination, as well as other gian explorer Roald Amund- destinations this ship visits Greenland 12 sen’s success as an explorer is during the 2019-2020 sailing often explained by his thor- season. We hope you will nd The Northwest Passage 16 ough preparations before this information inspiring. departure. He once said “vic- Contents tory awaits him who has every- We promise you an amazing Alaska 18 thing in order.” Being true to adventure! Amund sen’s heritage of good South America 20 planning, we encourage you to Welcome aboard for the ad- read this handbook. venture of a lifetime! Antarctica 24 It will provide you with good Your Hurtigruten Team Protecting the Antarctic advice, historical context, Environment from Invasive 28 practical information, and in- Species spiring information that will Environmental Commitment 30 Important Information 32 Frequently Asked Questions 33 Practical Information 34 Before and After Your Voyage Life on Board 38 MS Roald Amundsen Pack Like an Explorer 44 Our Team on Board 46 Landing by Small Boats 48 Important Phone Numbers 49 Maritime Expressions 49 MS Roald Amundsen 50 Deck Plan 2 3 COVER FRONT PHOTO: © HURTIGRUTEN © GREGORY SMITH HURTIGRUTEN SMITH GREGORY © COVER BACK PHOTO: © ESPEN MILLS HURTIGRUTEN CLIMATE Europe lies mainly lands and new trading routes.