The Emerging Vision Conflicts in Redeveloping Historic Nanjing, China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amcham Shanghai Nanjing Center

An Overview of AmCham Shanghai Nanjing Center Jan 2020 Stella Cai 1 Content ▪ About Nanjing Center ▪ Program & Services ▪ Membership Benefits ▪ Become a Member 2 About Nanjing Center The Nanjing Center was launched as an initiative in March 2016. The goal of the Center is to promote the interests of U.S. Community Connectivity Content business in Nanjing and is managed by the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai Yangtze River Delta Network. About Nanjing Center – Member Companies EASTMAN Honeywell Cushman Padel Wakefields Sports PMC Hopkins Nanjing Emerson Center Kimball Electronics KPMG Raffles Medical Herman Kay King & Wood Mallesons ▪ About Nanjing Center ▪ Program & Services ▪ Membership Benefits ▪ Become a Member 5 Programs & Services Government Dialogue & Dinner Government Affairs NEXT Summit US VISA Program Member Briefing US Tax Filing Leadership Forum Recruitment Platform Women’s Forum Customized Trainings Business Mixer Marketing & Sponsorship Topical Event Industry Committee Nanjing signature event 35 Nanjing government reps 6 American Government reps 150 to 200 execs from MNCs 2-hour R/T discussion + 2-hour dinner Monthly program focuses on politic & macro economy trend China & US Government officials, industry expert as speakers 2-hour informative session Topics: US-China trade relations; Tax reform, Financial sector opening & reform; Foreign investment laws; IPR; Tariffs exclusion 30-40 yr. manager Newly promoted s Grow management A platform & leadership 5 30 company employee speakers s AmCham granted Certificate Monthly -

Appendix 1: Rank of China's 338 Prefecture-Level Cities

Appendix 1: Rank of China’s 338 Prefecture-Level Cities © The Author(s) 2018 149 Y. Zheng, K. Deng, State Failure and Distorted Urbanisation in Post-Mao’s China, 1993–2012, Palgrave Studies in Economic History, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92168-6 150 First-tier cities (4) Beijing Shanghai Guangzhou Shenzhen First-tier cities-to-be (15) Chengdu Hangzhou Wuhan Nanjing Chongqing Tianjin Suzhou苏州 Appendix Rank 1: of China’s 338 Prefecture-Level Cities Xi’an Changsha Shenyang Qingdao Zhengzhou Dalian Dongguan Ningbo Second-tier cities (30) Xiamen Fuzhou福州 Wuxi Hefei Kunming Harbin Jinan Foshan Changchun Wenzhou Shijiazhuang Nanning Changzhou Quanzhou Nanchang Guiyang Taiyuan Jinhua Zhuhai Huizhou Xuzhou Yantai Jiaxing Nantong Urumqi Shaoxing Zhongshan Taizhou Lanzhou Haikou Third-tier cities (70) Weifang Baoding Zhenjiang Yangzhou Guilin Tangshan Sanya Huhehot Langfang Luoyang Weihai Yangcheng Linyi Jiangmen Taizhou Zhangzhou Handan Jining Wuhu Zibo Yinchuan Liuzhou Mianyang Zhanjiang Anshan Huzhou Shantou Nanping Ganzhou Daqing Yichang Baotou Xianyang Qinhuangdao Lianyungang Zhuzhou Putian Jilin Huai’an Zhaoqing Ningde Hengyang Dandong Lijiang Jieyang Sanming Zhoushan Xiaogan Qiqihar Jiujiang Longyan Cangzhou Fushun Xiangyang Shangrao Yingkou Bengbu Lishui Yueyang Qingyuan Jingzhou Taian Quzhou Panjin Dongying Nanyang Ma’anshan Nanchong Xining Yanbian prefecture Fourth-tier cities (90) Leshan Xiangtan Zunyi Suqian Xinxiang Xinyang Chuzhou Jinzhou Chaozhou Huanggang Kaifeng Deyang Dezhou Meizhou Ordos Xingtai Maoming Jingdezhen Shaoguan -

EDUCATION in CHINA a Snapshot This Work Is Published Under the Responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD

EDUCATION IN CHINA A Snapshot This work is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. Photo credits: Cover: © EQRoy / Shutterstock.com; © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © astudio / Shutterstock.com Inside: © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © li jianbing / Shutterstock.com; © tangxn / Shutterstock.com; © chuyuss / Shutterstock.com; © astudio / Shutterstock.com; © Frame China / Shutterstock.com © OECD 2016 You can copy, download or print OECD content for your own use, and you can include excerpts from OECD publications, databases and multimedia products in your own documents, presentations, blogs, websites and teaching materials, provided that suitable acknowledgement of OECD as source and copyright owner is given. All requests for public or commercial use and translation rights should be submitted to [email protected]. Requests for permission to photocopy portions of this material for public or commercial use shall be addressed directly to the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) at [email protected] or the Centre français d’exploitation du droit de copie (CFC) at [email protected]. Education in China A SNAPSHOT Foreword In 2015, three economies in China participated in the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment, or PISA, for the first time: Beijing, a municipality, Jiangsu, a province on the eastern coast of the country, and Guangdong, a southern coastal province. -

Effects of an Innovative Training Program for New Graduate Registered Nurses: A

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.11.20192468; this version posted September 11, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . Effects of an Innovative Training Program for New Graduate Registered Nurses: a Comparison Study Fengqin Xu 1*, Yinhe Wang 2*, Liang Ma 1, Jiang Yu 1, Dandan Li 1, Guohui Zhou 1, Yuzi Xu 3, Hailin Zhang 1, Yang Cao 4 1 The First Affiliated Hospital of Kangda College of Nanjing Medical University, the First People’s Hospital of Lianyungang, the Affiliated Lianyungang Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University, Lianyungang 222000, Jiangsu, China 2 Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, the Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing University Medical School, Nanjing, 210008, Jiangsu, China 3 Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310058, Zhejiang, China 4 Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Medical Sciences, Örebro University, Örebro 70182, Sweden * The authors contributed equally to this work. Correspondence authors: Yang Cao, Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Medical Sciences, Örebro University, Örebro 70182, Sweden. Email: [email protected] Hailin Zhang, the First Affiliated Hospital of Kangda College of Nanjing Medical University, the First People’s Hospital of Lianyungang, the Affiliated Lianyungang Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University, Lianyungang 222000, Jiangsu, China. 1 NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. -

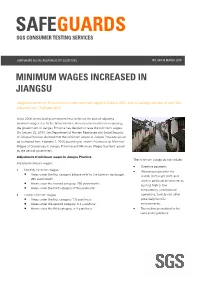

SGS-Safeguards 04910- Minimum Wages Increased in Jiangsu -EN-10

SAFEGUARDS SGS CONSUMER TESTING SERVICES CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIILITY SOLUTIONS NO. 049/10 MARCH 2010 MINIMUM WAGES INCREASED IN JIANGSU Jiangsu becomes the first province to raise minimum wages in China in 2010, with an average increase of over 12% effective from 1 February 2010. Since 2008, many local governments have deferred the plan of adjusting minimum wages due to the financial crisis. As economic results are improving, the government of Jiangsu Province has decided to raise the minimum wages. On January 23, 2010, the Department of Human Resources and Social Security of Jiangsu Province declared that the minimum wages in Jiangsu Province would be increased from February 1, 2010 according to Interim Provisions on Minimum Wages of Enterprises in Jiangsu Province and Minimum Wages Standard issued by the central government. Adjustment of minimum wages in Jiangsu Province The minimum wages do not include: Adjusted minimum wages: • Overtime payment; • Monthly minimum wages: • Allowances given for the Areas under the first category (please refer to the table on next page): middle shift, night shift, and 960 yuan/month; work in particular environments Areas under the second category: 790 yuan/month; such as high or low Areas under the third category: 670 yuan/month temperature, underground • Hourly minimum wages: operations, toxicity and other Areas under the first category: 7.8 yuan/hour; potentially harmful Areas under the second category: 6.4 yuan/hour; environments; Areas under the third category: 5.4 yuan/hour. • The welfare prescribed in the laws and regulations. CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIILITY SOLUTIONS NO. 049/10 MARCH 2010 P.2 Hourly minimum wages are calculated on the basis of the announced monthly minimum wages, taking into account: • The basic pension insurance premiums and the basic medical insurance premiums that shall be paid by the employers. -

Jiangsu(PDF/288KB)

Mizuho Bank China Business Promotion Division Jiangsu Province Overview Abbreviated Name Su Provincial Capital Nanjing Administrative 13 cities and 45 counties Divisions Secretary of the Luo Zhijun; Provincial Party Li Xueyong Committee; Mayor 2 Size 102,600 km Shandong Annual Mean 16.2°C Jiangsu Temperature Anhui Shanghai Annual Precipitation 861.9 mm Zhejiang Official Government www.jiangsu.gov.cn URL Note: Personnel information as of September 2014 [Economic Scale] Unit 2012 2013 National Share (%) Ranking Gross Domestic Product (GDP) 100 Million RMB 54,058 59,162 2 10.4 Per Capita GDP RMB 68,347 74,607 4 - Value-added Industrial Output (enterprises above a designated 100 Million RMB N.A. N.A. N.A. N.A. size) Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery 100 Million RMB 5,809 6,158 3 6.3 Output Total Investment in Fixed Assets 100 Million RMB 30,854 36,373 2 8.2 Fiscal Revenue 100 Million RMB 5,861 6,568 2 5.1 Fiscal Expenditure 100 Million RMB 7,028 7,798 2 5.6 Total Retail Sales of Consumer 100 Million RMB 18,331 20,797 3 8.7 Goods Foreign Currency Revenue from Million USD 6,300 2,380 10 4.6 Inbound Tourism Export Value Million USD 328,524 328,857 2 14.9 Import Value Million USD 219,438 221,987 4 11.4 Export Surplus Million USD 109,086 106,870 3 16.3 Total Import and Export Value Million USD 547,961 550,844 2 13.2 Foreign Direct Investment No. of contracts 4,156 3,453 N.A. -

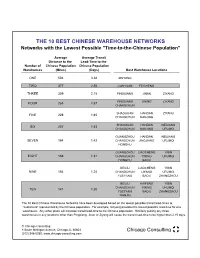

10 BEST CHINESE WAREHOUSE NETWORKS Networks with the Lowest Possible "Time-To-The-Chinese Population"

THE 10 BEST CHINESE WAREHOUSE NETWORKS Networks with the Lowest Possible "Time-to-the-Chinese Population" Average Average Transit Distance to the Lead-Time to the Number of Chinese Population Chinese Population Warehouses (Miles) (Days) Best Warehouse Locations ONE 504 3.38 XINYANG TWO 377 2.55 LIANYUAN FEICHENG THREE 309 2.15 PINGXIANG JINAN ZIYANG PINGXIANG JINING ZIYANG FOUR 265 1.87 CHANGCHUN SHAOGUAN HANDAN ZIYANG FIVE 228 1.65 CHANGCHUN NANJING SHAOGUAN HANDAN NEIJIANG SIX 207 1.53 CHANGCHUN NANJING URUMQI GUANGZHOU HANDAN NEIJIANG SEVEN 184 1.42 CHANGCHUN JINGJIANG URUMQI HONGHU GUANGZHOU LIAOCHENG YIBIN EIGHT 168 1.31 CHANGCHUN YIXING URUMQI HONGHU BAOJI BEILIU LIAOCHENG YIBIN NINE 154 1.24 CHANGCHUN LIYANG URUMQI YUEYANG BAOJI ZHANGZHOU BEILIU KAIFENG YIBIN CHANGCHUN YIXING URUMQI TEN 141 1.20 YUEYANG BAOJI ZHANGZHOU TIANJIN The 10 Best Chinese Warehouse Networks have been developed based on the lowest possible transit lead-times to "customers" represented by the Chinese population. For example, Xinyang provides the lowest possible lead-time for one warehouse. Any other place will increase transit lead-time to the Chinese population. Similarly putting any three warehouses in any locations other than Pingxiang, Jinan or Ziyang will cause the transit lead-time to be higher than 2.15 days. © Chicago Consulting 8 South Michigan Avenue, Chicago, IL 60603 Chicago Consulting (312) 346-5080, www.chicago-consulting.com THE 10 BEST CHINESE WAREHOUSE NETWORKS Networks with the Lowest Possible "Time-to-the-Chinese Population" Best One City -

Teravr Empowers Precise Reconstruction of Complete 3-D Neuronal Morphology in the Whole Brain

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11443-y OPEN TeraVR empowers precise reconstruction of complete 3-D neuronal morphology in the whole brain Yimin Wang 1,2,3,14,QiLi2, Lijuan Liu1, Zhi Zhou1,4, Zongcai Ruan1, Lingsheng Kong2, Yaoyao Li5, Yun Wang4, Ning Zhong6,7, Renjie Chai8,9,10, Xiangfeng Luo2, Yike Guo11, Michael Hawrylycz4, Qingming Luo12, Zhongze Gu 13, Wei Xie 8, Hongkui Zeng 4 & Hanchuan Peng 1,4,14 1234567890():,; Neuron morphology is recognized as a key determinant of cell type, yet the quantitative profiling of a mammalian neuron’s complete three-dimensional (3-D) morphology remains arduous when the neuron has complex arborization and long projection. Whole-brain reconstruction of neuron morphology is even more challenging as it involves processing tens of teravoxels of imaging data. Validating such reconstructions is extremely laborious. We develop TeraVR, an open-source virtual reality annotation system, to address these challenges. TeraVR integrates immersive and collaborative 3-D visualization, interaction, and hierarchical streaming of teravoxel-scale images. Using TeraVR, we have produced precise 3-D full morphology of long-projecting neurons in whole mouse brains and developed a collaborative workflow for highly accurate neuronal reconstruction. 1 Southeast University – Allen Institute Joint Center, Institute for Brain and Intelligence, Southeast University, Nanjing 210096, China. 2 School of Computer Engineering and Science, Shanghai University, Shanghai 200444, China. 3 Shanghai Institute for Advanced Communication and Data Science, Shanghai University, Shanghai 200444, China. 4 Allen Institute for Brain Science, Seattle 98109, USA. 5 School of Optometry and Ophthalmology, Wenzhou Medical University, Wenzhou 325027, China. -

CHEN-DISSERTATION-2018.Pdf (7.947Mb)

DISCLAIMER: This document does not meet current format guidelines Graduate School at the The University of Texas at Austin. of the It has been published for informational use only. Copyright by Yu Chen 2018 The Dissertation Committee for Yu Chen Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Dissertation: Advance in Housing Right or Accumulation by Dispossession? How Social Housing Is Used as Policy Tool to Promote Neoliberal Urban Development in China and in Mexico Committee: Peter M. Ward, Supervisor Bryan R. Roberts, Co-Supervisor Mounira M. Charrad Néstor P. Rodríguez Joshua Eisenman Edith R. Jiménez Huerta Advance in Housing Right or Accumulation by Dispossession? How Social Housing Is Used as Policy Tool to Promote Neoliberal Urban Development in China and in Mexico by Yu Chen Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2018 Acknowledgements I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my committee chairs, Dr. Peter M. Ward and Dr. Bryan R. Roberts, for their constant support and intellectual guidance. Their commitment to research and scholarship have inspired me throughout my graduate career. They have been such wonderful and dedicated mentors, and I cannot thank them enough for nurturing my academic enthusiasm. I would like to thank my committee members, Dr. Mounira M. Charrad, Dr. Néstor P. Rodríguez and Dr. Joshua Eisenman, for their extensive help in my dissertation research and writing. Their comments and feedbacks on my dissertation also motivated me to envision future research projects. -

Delimitating Urban Commercial Central Districts by Combining Kernel Density Estimation and Road Intersections: a Case Study in Nanjing City, China

International Journal of Geo-Information Article Delimitating Urban Commercial Central Districts by Combining Kernel Density Estimation and Road Intersections: A Case Study in Nanjing City, China Jing Yang 1,2, Jie Zhu 3 , Yizhong Sun 1,2,* and Jianhua Zhao 4 1 Key Laboratory of Virtual Geographic Environment of Ministry of Education, Nanjing Normal University, Nanjing 210023, China; [email protected] 2 Jiangsu Center for Collaborative Innovation in Geographical Information Resource Development and Application, Nanjing 210023, China 3 College of Civil Engineering, Nanjing Forestry University, Nanjing 210037, China; [email protected] 4 Lishui City Geographic Information Center, Lishui 323000, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-137-7082-7090 Received: 30 November 2018; Accepted: 8 February 2019; Published: 16 February 2019 Abstract: An urban, commercial central district is often regarded as the heart of a city. Therefore, quantitative research on commercial central districts plays an important role when studying the development and evaluation of urban spatial layouts. However, conventional planar kernel density estimation (KDE) and network kernel density estimation (network KDE) do not reflect the fact that the road network density is high in urban, commercial central districts. To solve this problem, this paper proposes a new method (commercial-intersection KDE), which combines road intersections with KDE to identify commercial central districts based on point of interest (POI) data. First, we extracted commercial POIs from Amap (a Chinese commercial, navigation electronic map) based on existing classification standards for urban development land. Second, we calculated the commercial kernel density in the road intersection neighborhoods and used those values as parameters to build a commercial intersection density surface. -

Spatial Distribution Pattern of Minshuku in the Urban Agglomeration of Yangtze River Delta

The Frontiers of Society, Science and Technology ISSN 2616-7433 Vol. 3, Issue 1: 23-35, DOI: 10.25236/FSST.2021.030106 Spatial Distribution Pattern of Minshuku in the Urban Agglomeration of Yangtze River Delta Yuxin Chen, Yuegang Chen Shanghai University, Shanghai 200444, China Abstract: The city cluster in Yangtze River Delta is the core area of China's modernization and economic development. The industry of Bed and Breakfast (B&B) in this area is relatively developed, and the distribution and spatial pattern of Minshuku will also get much attention. Earlier literature tried more to explore the influence of individual characteristics of Minshuku (such as the design style of Minshuku, etc.) on Minshuku. However, the development of Minshuku has a cluster effect, and the distribution of domestic B&Bs is very unbalanced. Analyzing the differences in the distribution of Minshuku and their causes can help the development of the backward areas and maintain the advantages of the developed areas in the industry of Minshuku. This article finds that the distribution of Minshuku is clustered in certain areas by presenting the overall spatial distribution of Minshuku and cultural attractions in Yangtze River Delta and the respective distribution of 27 cities. For example, Minshuku in the central and eastern parts of Yangtze River Delta are more concentrated, so are the scenic spots in these areas. There are also several concentrated Minshuku areas in other parts of Yangtze River Delta, but the number is significantly less than that of the central and eastern regions. Keywords: Minshuku, Yangtze River Delta, Spatial distribution, Concentrated distribution 1. -

Jiangsu Companies Registered at the 7 CITTC(By 2020.9.9) Next Generation Information Technologies 1 Econergy (Nanjing) Institute Co., Ltd

th Jiangsu Companies Registered at the 7 CITTC(By 2020.9.9) Next Generation Information Technologies 1 Econergy (Nanjing) institute Co., Ltd. 2 Nantong Suyuantian Electric Testing&Repairing Installation Project Co., Ltd. 3 Zhongcheng Blockchain Research Institute 4 Nanjing Iron& Steel Co., Ltd. 5 Jiangsu University of Technology 6 Jiangsu Jianqiao Painting Engineering Co., Ltd. 7 Jiangsu Zhitong Traffic Science and Technology Ltd. 8 Xing Huan Zhong Zhi Information Technology (Nanjing) Co., Ltd. 9 Southeast University Intelligent Tranportation System(ITS)Research Centre 10 Hengtong Submarine Power Cable Co., Ltd. 11 Jiangsu Sanleng Smart City & IOT System Co., Ltd. 12 Nanjing Fancy Transportation Technology Co., Ltd. 13 Easyway(SuZhou) Electronics Technology Co., Ltd. 14 iFLYTEK (Suzhou) Technology Co., Ltd. 15 Suzhou Tongji Blockchain Research Institute 16 Suzhou Wuzhong Zhongke S&T Incubation Development Co., Ltd. 17 Nanjing Inrich Technology Co., Ltd. 18 Nanjing Institute of Electronic and Technology 19 JointForce Interternet Co., Ltd. 20 Jiangsu R&D Center for Internet of Things 21 Suzhou Yuta Technology Co., Ltd. New Materials 1 Champion Chemicals(Yangzhou) Co., Ltd. 2 Jiangsu Jin Rui Hei Technology Co., Ltd 3 Jiangsu Jianghangzhi Areoplane Engine Research Institution Co., Ltd. 4 Jiangsu University of Technology 5 Nantong Suyuantian Electric Testing&Repairing Installation Project Co., Ltd. 6 Nanjing Wondux Environmental Protection Technology Corp., Ltd. 7 Nanjing Institute for Intelligent Additive Manufacturing Company 8 Nanjing Iron& Steel Co., Ltd. 9 Kangde Xin Optical Film Materials Co., Ltd. 10 Jiangsu Atonepoint Technology Co., Ltd. 11 Jiangsu Jianqiao Painting Engineering Co.,Ltd. 12 Jiangsu Hewa Screening Product Co., Ltd. 13 Nanjing Shuangwei Biotechnology Co., Ltd.