Ethical Fashion Initiative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

Fashion and Contemporary Arts

TRACK: FASHION STYLING IED FIRENZE DESCRIPTION OF INDIVIDUAL COURSE Course Title Fashion and Contemporary Arts Semester Spring Teaching Method Theory Lessons Total Hours Total Hours Theoretical Theory Lessons 36 Lab – project 3 workshop (1 hour = 60 minutes) (1 hour = 60 minutes) Practical workshop Credits 3 The goal of this course is to provide students with the necessary techniques to analyze fashion as a cultural phenomenon from an interdisciplinary point of view, as a cultural phenomenon, using the appropriate vocabulary and to enable them to understand the social condition of the wearers. Ideally, at the conclusion of the course they will have learned to consider of a work of art through the use of new critical tools; and they will achieve a global understanding of the Western fashion historic timeline, protagonists, revolutions, changes. We’ll focus on Italian fashion and a series of characteristics that could Learning be summarized as the International, European, and Italian style. Then the class continues studying the language and system Objectives of fashion. Specific designers are studied and presented in class during Professor’s lectures, student’s assignments, and oral presentations. During each term a selection among the designers is discussed and presented during the classes. In this course the relationship between fashion and media is stressed. Media have tremendously impacted the fashion history, and they are still shaping the industry, that’s why students by the end of the course need to be aware of who are the new protagonists that are writing now the fashion history of the future. The course explores the historical development of contemporary fashion in order to identify trends in the fashion industry and the communication process. -

Pop / Rock / Commercial Music Wed, 25 Aug 2021 21:09:33 +0000 Page 1

Pop / Rock / Commercial music www.redmoonrecords.com Artist Title ID Format Label Print Catalog N° Condition Price Note 10000 MANIACS The wishing chair 19160 1xLP Elektra Warner GER 960428-1 EX/EX 10,00 € RE 10CC Look hear? 1413 1xLP Warner USA BSK3442 EX+/VG 7,75 € PRO 10CC Live and let live 6546 2xLP Mercury USA SRM28600 EX/EX 18,00 € GF-CC Phonogram 10CC Good morning judge 8602 1x7" Mercury IT 6008025 VG/VG 2,60 € \Don't squeeze me like… Phonogram 10CC Bloody tourists 8975 1xLP Polydor USA PD-1-6161 EX/EX 7,75 € GF 10CC The original soundtrack 30074 1xLP Mercury Back to EU 0600753129586 M-/M- 15,00 € RE GF 180g black 13 ENGINES A blur to me now 1291 1xCD SBK rec. Capitol USA 7777962072 USED 8,00 € Original sticker attached on the cover 13 ENGINES Perpetual motion 6079 1xCD Atlantic EMI CAN 075678256929 USED 8,00 € machine 1910 FRUITGUM Simon says 2486 1xLP Buddah Helidon YU 6.23167AF EX-/VG+ 10,00 € Verty little woc COMPANY 1910 FRUITGUM Simon says-The best of 3541 1xCD Buddha BMG USA 886972424422 12,90 € COMPANY 1910 Fruitgum co. 2 CELLOS Live at Arena Zagreb 23685 1xDVD Masterworks Sony EU 0888837454193 10,90 € 2 UNLIMITED Edge of heaven (5 vers.) 7995 1xCDs Byte rec. EU 5411585558049 USED 3,00 € 2 UNLIMITED Wanna get up (4 vers.) 12897 1xCDs Byte rec. EU 5411585558001 USED 3,00 € 2K ***K the millennium (3 7873 1xCDs Blast first Mute EU 5016027601460 USED 3,10 € Sample copy tracks) 2PLAY So confused (5 tracks) 15229 1xCDs Sony EU NMI 674801 2 4,00 € Incl."Turn me on" 360 GRADI Ba ba bye (4 tracks) 6151 1xCDs Universal IT 156 762-2 -

Spate of Warnings Paints Grim Picture Last Week, Kohl’S Corp., Macy’S by EVAN CLARK Inc

GIRLS, GIRLS, OSCAR’S NEW BLUE GIRLS MATRIMONY INSPIRES DE LA RENTA’S LENA DUNHAM LATEST FRAGRANCE. PAGE 6 AND CREW FETE THE PREMIERE OF THEIR HBO SHOW’S SECOND SEASON. PAGE 10 COLLECTIONS PRE-FALL 2013 WWDFRIDAY, JANUARY 11, 2013 ■ WOMEN’S WEAR DAILY ■ $3.00 RETAIL’S UNEASY FEELING Spate of Warnings Paints Grim Picture Last week, Kohl’s Corp., Macy’s By EVAN CLARK Inc. and Target Corp. all issued earnings guidance that fell short THE FOURTH-QUARTER outlook of analyst projections. isn’t getting any prettier. Investors took the day to reas- Tiffany & Co., Aéropostale Inc. sess and retail stocks rallied into and Ascena Retail Group Inc. all positive territory late in the day. The cut profit projections Thursday, sector is still near its all-time high. weighing on retail stocks and re- The S&P 500 Retailing Industry confirming the generally blah Group rose 0.4 percent, or 2.41 reading of the holiday season. points, to 666.52. The sector is up Tiffany said its comparable-store 1.9 percent so far this year. sales were fl at for November and The Dow Jones Industrial December and that comps at its Average rose 0.6 percent, or 80.71 New York fl agship fell 2 percent. points, to 13,471.22 for the day. Michael Kowalski, chairman Shares of Ascena dropped 7 percent and chief executive offi cer of the to $16.86, as Tiffany declined 4.5 luxe jeweler, said, “Holiday pe- percent to $60.40 and Aéropostale riod sales growth was at the low slipped 1 percent to $13.24. -

2021 SANE Catalog

2021 CATALOG Today’s Classroom Supplies at Affordable Prices for your Family & Consumer Science Department. Check out our new Kits! Now in our 45th YEAR! 800-262-8653 Visit our website at Due to ever changing www.sanefcs.com market conditions, please check our website for Fax: 513-894-3100 • Email: [email protected] current availability and pricing. 2275 MILLVILLE AVE., SUITE 1 • HAMILTON, OH 45013 Pins 10102 Bonus Pack Dressmaker Pins - 750 count, size 17 pins by Dritz, STRAIGHT PINS extra large amount for extra savings! Re-closeable plastic box .............$ 5.45 SIZE INCHES 10105 Dressmaker Pins, ½ lb. Box - 1-1/16” size 17 silk pins from Size 17 1-1/16” Prym’s, approximately 2,500 pins per box ................................................ 7.50 Size 20 1-1/4” Size 22 1-3/8” 10106 Dressmaker Pins, 1 lb Box - BEST VALUE!, same 1-1/16” size Size 24 1-1/2” 17 silk pins, approximately 5,000 pins per box, from Prym’s .................. 11.75 10105 Size 28 1-3.4” Size 30 1-7/8” 10111 Ballpoint Dressmaker Pins - 600 ballpoint pins in a re-sealable 10106 package, for medium weight and knit fabrics, from Dritz, size 17 ............ 3.95 10116 Ballpoint Plastic Head Pins - 175 size 17 pins per box, 1-1/16” long, Dressmaker Pins — Medium Shaft extra fine shaft, colorful plastic heads, for knits & fine fabrics, from Dritz . 2.95 Silk/Satin Pins — Thin Shaft Extra Fine Pins — Thinnest Shaft 10115 Plastic Head Pins - 200 pins, 1-1/16” long size 17 pins, colorful plastic heads, recloseable plastic box, from Dritz ....................... -

Lacoste at 80 Fashion Week Got Into Full Snow-Covered Stride Heading Into the Weekend with Collections Including Kenneth Cole, Kate Spade, Nautica and Lyn Devon

WWDMILESTONES SECTION II LACOSTE AT 80 FASHION WEEK GOT INTO FULL SNOW-COVERED STRIDE HEADING INTO THE WEEKEND WITH COLLECTIONS INCLUDING KENNETH COLE, KATE SPADE, NAUTICA AND LYN DEVON. PAGE 4 NEMO’S WRATH Blizzard Hits Retail As Shows Must Go On By WWD STAFF AH, AS SUZY MENKES recalls, for the New York shows of yore “in the crispness of October and the lovely beginning of spring.” Instead, there’s a blizzard. Scores of stores closed early Friday in the Tristate WEEKEND, FEBRUARY 9, 2013 Q $3.00 Q WOMEN’S WEAR DAILY area due to Winter Storm Nemo even as designers and the fashion pack soldiered on through New York WWD Fashion Week — although many European buyers and journalists, including Menkes herself, could not get to New York because of canceled flights. The clothes on the runway suddenly looked perfectly timely for the weather outside even as many fashion folk refused to give in and stuck to their vertiginous heels, short skirts and flowy dresses, snow and slush be damned. Winter Storm Nemo hit New York on Friday. PHOTO BY STEVE EICHNER PHOTO BY None of the fashion shows were canceled or post- poned as of press time Friday, with most design- ers due to show today saying they were sticking to the schedule. A spokeswoman for IMG, which owns Mercedes-Benz Fashion Week, said Friday, “We have been in constant contact throughout the night and into this morning with city officials, including the Mayor’s office, the NYPD, Council of Fashion Designers of America, the Department of Sanitation and the Department of Buildings. -

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie 2014 T 01

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie Reihe T Musiktonträgerverzeichnis Monatliches Verzeichnis Jahrgang: 2014 T 01 Stand: 22. Januar 2014 Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (Leipzig, Frankfurt am Main) 2014 ISSN 1613-8945 urn:nbn:de:101-ReiheT01_2014-4 2 Hinweise Die Deutsche Nationalbibliografie erfasst eingesandte Pflichtexemplare in Deutschland veröffentlichter Medienwerke, aber auch im Ausland veröffentlichte deutschsprachige Medienwerke, Übersetzungen deutschsprachiger Medienwerke in andere Sprachen und fremdsprachige Medienwerke über Deutschland im Original. Grundlage für die Anzeige ist das Gesetz über die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (DNBG) vom 22. Juni 2006 (BGBl. I, S. 1338). Monografien und Periodika (Zeitschriften, zeitschriftenartige Reihen und Loseblattausgaben) werden in ihren unterschiedlichen Erscheinungsformen (z.B. Papierausgabe, Mikroform, Diaserie, AV-Medium, elektronische Offline-Publikationen, Arbeitstransparentsammlung oder Tonträger) angezeigt. Alle verzeichneten Titel enthalten einen Link zur Anzeige im Portalkatalog der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek und alle vorhandenen URLs z.B. von Inhaltsverzeichnissen sind als Link hinterlegt. Die Titelanzeigen der Musiktonträger in Reihe T sind, wie sche Katalogisierung von Ausgaben musikalischer Wer- auf der Sachgruppenübersicht angegeben, entsprechend ke (RAK-Musik)“ unter Einbeziehung der „International der Dewey-Dezimalklassifikation (DDC) gegliedert, wo- Standard Bibliographic Description for Printed Music – bei tiefere Ebenen mit bis zu sechs Stellen berücksichtigt ISBD (PM)“ zugrunde. -

No- Holds Bold

CIVIL SOUNDS FOR FIT CIVIL TWILIGHT HAS FANATIC STEADILY BUILT A RABID CYNTHIA ROWLEY FAN BASE AND IS NOW SILVANA UNVEILS AN SET TO PERFORM AT THE FENDI UNVEILS A CAPSULE EXPANDED LINE OF SOUTH BY SOUTHWEST TRAVEL COLLECTION IN FITNESS APPAREL. FESTIVAL. PAGE 10 HONOR OF ITALIAN ACTRESS SILVANA MANGANO. PAGE 11 PAGE 9 FASHION WEEK BEGINS Japan’s Designers Adapt to Economy By AMANDA KAISER TOKYO — As the fashion pack barely catches its col- lective breath from the conclusion of the Paris shows, Tokyo Fashion Week starts today, with designers here voicing optimism despite the looming challenges of growing their small businesses and a domestic economy MONDAY, MARCH 16, 2015 ■ $3.00 ■ WOMEN’S WEAR DAILY that continues to sputter. WWD Future prospects look mixed. On the one hand, Japan is struggling to climb out of a recession and local consumers remain cautious about spending. On the other, tourists from elsewhere in Asia are fl ood- FIT FANATIC ing the country to take advantage of a weak yen and shop. While most Japanese designers still do the bulk of their business in their home country, the currency Cynthia Rowley unveils an factor stands to boost the nation’s fashion exports. expanded line of fi tness Designers are going to need all the overseas help they can get. Last week, Japan revised down its apparel. PAGE 9 fourth-quarter GDP fi gures to show that the econo- my grew at an annualized rate of 1.5 percent in the October to December period — the initial estimate pegged growth at 2.2 percent. -

Icky to Some, Delicacy to Others Employees Remove Feathers from Chicken Heads at a Chicken-Processing Factory in Suining, Southwest China’S Sichuan Province

SPRING THE FORWARD! COURTSHIP Sunday, March 11 BEGINS Daylight savings until the Winnipeg’s grain industry first Sunday in November wooed by other cities » PAGE 17 March 8, 2012 SerVinG Manitoba FarMerS Since 1925 | Vol. 70, No. 10 | $1.75 Manitobacooperator.ca CGC back on drawing board Proposals include ending mandatory inward inspection By Allan Dawson CO-OPERATOR STAFF h e C a n a d i a n G r a i n Commission is on the fed- T eral government’s radar — again. Last month the commission announced its latest proposals for “modernizing” itself, and the Canada Grain Act it administers. The public has until March 23 to respond. The commission, established in 1912, is Canada’s grain indus- try watchdog, ensuring the qual- ity of grain exports, arbitrating grade disputes between farmers and buyers, licensing grain com- panies and ensuring buyers post See CGC on page 6 » Employees remove feathers from chicken heads at a chicken-processing factory in Suining, southwest China’s Sichuan province. REUTERS/STRINGER (CHINA) Icky to some, delicacy to others Chicken feet worth more than chicken breasts in some Asian markets By Allan Dawson North American livestock producers, says When it comes to producing meat, North CO-OPERATOR STAFF Dermot Hayes, an agricultural economist America already has a competitive advan- from Iowa State University and the 2012 tage, which would be enhanced by export- he sight of a pretty Chinese girl pre- Kraft Lecturer. ing to Asia the animal’s parts thrown out paring to gobble down a cooked Hayes said the emerging markets for here, but command a premium over there. -

September 11, 1997 Ultestlanft (Dbseruer Putting You in Touch with Your World

Playscape dream becoming a reality, A6 Thursday & September 11, 1997 Ultestlanft (Dbseruer Putting You In Touch With Your World VOLUME 33 NUMBER 28 WESTLAND, MICHIGAN • 76 PAGES • http://observer-eccentric.com SEVENTY-FIVE CENTS O 1897 HomeTbwn Communication! Network, Inc. - ifca* IN THE PAPER WESTIAND'S San, 9 PRIMARY f %<&*< ELECTION Thomas, Mehl win race RESULTS TODAY Mayor Robert Thomas and challenger Ken ers bothered to vote, marking a paltry MAYOR neth Mehl will face off Nov. 4 in the general 10.7 percent turnout. (Top two will move on to Nov. 4 general election) One week after his 47th birthday, a election following Tuesday's primary elec • Dixie Johnson McNa - 375 jubilant Thomas celebrated victory • Kenneth Mehl-1.502 Information, please: Infor tion in Westland. Candidate Dixie Johnson Tuesday as more than 200 supporters mation Central, from the McNa was defeated in Tuesday's voting. poured into his election-night head • Robert Thomae <incumt»nt) • 4,002 BY DARRELL CLEM manded 67.3 percent of vote totals to quarters at the senior citizen Friend William P. Faust Public ship Center on Newburgh. STAFF WRITER emerge unmistakably as a front-runner executive secretary to purchasing Library of Westland, for another four-year term. "I feel good about this," he told the Incumbent Westland Mayor Robert Observer. "I think it shows that people agent and raising her salary by several offers details on library Thomas, winning the top spot in Tues Mehl, a former 12-year council mem- thousand dollars. ber, ^survived the primary with a mere wanted to vote for me because they programs. -

Op Title List Since Date: Apr 2, 2020

Op Title List since Date: Apr 2, 2020 Publisher Imprint ISBN Title Author Pub Pub Format Status Status Last Month Price Date Return Date Audio Audio 1427209278 BEHIND THE WHEEL EXPRESS - FRENCH 1 BEHIND THE WHEEL 07/10 19.99 CD OP 06/01/20 08/30/20 Audio Audio 1427252068 24: DEADLINE SWALLOW, JAMES 08/14 26.99 DA OP 05/26/20 08/24/20 Audio Audio 1427258449 24: DEADLINE SWALLOW, JAMES 08/14 49.99 DA OP 05/26/20 08/24/20 Audio Audio 1427258457 24: DEADLINE SWALLOW, JAMES 08/14 69.99 PW OP 05/26/20 08/24/20 Audio Audio 1427258465 24: DEADLINE SWALLOW, JAMES 08/14 59.99 CD OP 05/26/20 08/24/20 Audio Audio 1427265070 24: ROGUE MACK, DAVID 09/15 26.99 DA OP 05/26/20 08/24/20 Audio Audio 1427270317 24: DEADLINE SWALLOW, JAMES 08/14 3.99 DA OP 05/26/20 08/24/20 Audio Audio 1427275165 24: ROGUE MACK, DAVID 09/15 54.99 DA OP 05/26/20 08/24/20 Audio Audio 1427275955 24: ROGUE MACK, DAVID 09/15 59.99 CD OP 05/26/20 08/24/20 Audio Audio 1593975317 DRAGON REBORN UAB CD JORDAN, ROBERT 11/04 84.99 CD OP 06/01/20 08/30/20 Distribution Bloomsbury Adult 0747589321 MUSHROOMS WRIGHT, JOHN 05/14 25 TC OP 06/02/20 08/31/20 Distribution Bloomsbury Adult 0747599394 TO THE WEDDING BERGER, JOHN 06/09 17 TP OP 04/17/20 07/16/20 Distribution Bloomsbury Adult 0802743633 NABOKOV IN AMERICA ROPER, ROBERT 06/15 28 TC OP 06/02/20 08/31/20 Distribution Bloomsbury Adult 1408154927 SECRET OLYMPIAN ANON, 07/12 14.95 TP OP 04/17/20 07/16/20 Distribution Bloomsbury Adult 1408824329 WHO MOVED MY STILTON? TYERS, ALAN 11/12 19 TC OP 04/17/20 07/16/20 Distribution Bloomsbury Adult -

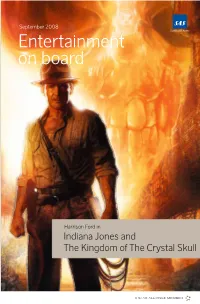

Entertainment on Board

September 2008 Entertainment on board Harrison Ford in Indiana Jones and The Kingdom of The Crystal Skull SAS SEP08_OMSLAG_INDEX_MJ.indd 1 08-08-14 15.06.41 Family To help you locate it Movies more easily, we have The Chronicles of Narnia: Prince Caspian 11 highlighted family Kung Fu Panda 12 entertainment in Finding Nemo 12 yellow. Music Children 22 Games Elephant Memory 32 Invasion 33 Kung Fu Panda SAS SEP08_OMSLAG_INDEX_MJ.indd 2 08-08-14 15.06.47 Welcome aboard I hope you’re sitting comfortably. To make your flight with us today even more enjoy- able, please let us entertain you with our wide selection of movies, music and games. Our in-flight entertainment programme aims to offer something for everyone, whether you want to laugh or cry, be informed or entertained. And for the little ones, we have a number of choices, with all Family Programming highlighted in yellow. This month we’re showing the second film about the Pevensie children when they re- turn to the Land of Narnia, where one thousand years have passed since they were last there and they must fight against evil to ensure that the lawful prince can rule the land. We’re also showing this summer’s big family success, the animated “Kung Fu Panda”, and giving you another chance of enjoying Pixar’s much acclaimed “Finding Nemo”. And for those looking for a little more adventure, everyone’s favourite Dr. Jones is returning in “Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal skull. We hope you have an enjoyable and entertaining flight.