Comparing Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells Cell Walls of Bacteria Cell Envelope Structure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review Article: Inhibition of Methanogenic Archaea by Statins As a Targeted Management Strategy for Constipation and Related Disorders

Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics Review article: inhibition of methanogenic archaea by statins as a targeted management strategy for constipation and related disorders K. Gottlieb*, V. Wacher*, J. Sliman* & M. Pimentel† *Synthetic Biologics, Inc., Rockville, SUMMARY MD, USA. † Gastroenterology, Cedars-Sinai Background Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, USA. Observational studies show a strong association between delayed intestinal transit and the production of methane. Experimental data suggest a direct inhibitory activity of methane on the colonic and ileal smooth muscle and Correspondence to: a possible role for methane as a gasotransmitter. Archaea are the only con- Dr K. Gottlieb, Synthetic Biologics, fi Inc., 9605 Medical Center Drive, rmed biological sources of methane in nature and Methanobrevibacter Rockville, MD 20850, USA. smithii is the predominant methanogen in the human intestine. E-mail: [email protected] Aim To review the biosynthesis and composition of archaeal cell membranes, Publication data archaeal methanogenesis and the mechanism of action of statins in this context. Submitted 8 September 2015 First decision 29 September 2015 Methods Resubmitted 7 October 2015 Narrative review of the literature. Resubmitted 20 October 2015 Accepted 20 October 2015 Results EV Pub Online 11 November 2015 Statins can inhibit archaeal cell membrane biosynthesis without affecting This uncommissioned review article was bacterial numbers as demonstrated in livestock and humans. This opens subject to full peer-review. the possibility of a therapeutic intervention that targets a specific aetiologi- cal factor of constipation while protecting the intestinal microbiome. While it is generally believed that statins inhibit methane production via their effect on cell membrane biosynthesis, mediated by inhibition of the HMG- CoA reductase, there is accumulating evidence for an alternative or addi- tional mechanism of action where statins inhibit methanogenesis directly. -

The Methanosarcina Barkeri Genome

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Title The Methanosarcina barkeri genome: comparative analysis with Methanosarcina acetivorans and Methanosarcina mazei reveals extensive rearrangement within methanosarcinal genomes Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3g16p0m7 Authors Maeder, Dennis L. Anderson, Iain Brettin, Thomas S. et al. Publication Date 2006-05-19 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California LBNL-60247 Preprint Title: The Methanosarcina barkeri genome: comparative analysis with Methanosarcina acetivorans and Methanosarcina mazei reveals extensive rearrangement within methanosarcinal genomes Author(s): Dennis L. Maeder, Iain Anderson, et al Division: Genomics November 2006 Journal of Bacteriology Maeder et al. May 18, 2006 1 2 The Methanosarcina barkeri genome: comparative analysis 3 with Methanosarcina acetivorans and Methanosarcina mazei 4 reveals extensive rearrangement within methanosarcinal 5 genomes 6 7 8 9 Dennis L. Maeder*, Iain Anderson†, Thomas S. Brettin†, David C. Bruce†, Paul Gilna†, 10 Cliff S. Han†, Alla Lapidus†, William W. Metcalf‡, Elizabeth Saunders†, Roxanne 11 Tapia†, and Kevin R. Sowers*. 12 13 * University of Maryland Biotechnology Institute, Center of Marine Biotechnology, 14 Columbus Center, Suite 236, 701 E. Pratt St., Baltimore, Maryland 21202, USA 15 † Microbial Genomics, DOE Joint Genome Institute, 2800 Mitchell Drive, B400, Walnut 16 Creek, CA 94598, USA 17 ‡ University of Illinois, Department of Microbiology, B103 Chemical and Life Sciences 18 Laboratory, 601 S. Goodwin Avenue, Urbana, Illinois 61801, USA 19 20 Running title: Comparative analysis of three methanosarcinal genomes 21 22 Keywords: Methanosarcina barkeri, archaeal genome, methanogenic Archaea 1 Maeder et al. May 18, 2006 23 ABSTRACT 24 25 We report here a comparative analysis of the genome sequence of 26 Methanosarcina barkeri with those of Methanosarcina acetivorans and 27 Methanosarcina mazei. -

Phylogenomic Networks Reveal Limited Phylogenetic Range of Lateral Gene Transfer by Transduction

The ISME Journal (2017) 11, 543–554 OPEN © 2017 International Society for Microbial Ecology All rights reserved 1751-7362/17 www.nature.com/ismej ORIGINAL ARTICLE Phylogenomic networks reveal limited phylogenetic range of lateral gene transfer by transduction Ovidiu Popa1, Giddy Landan and Tal Dagan Institute of General Microbiology, Christian-Albrechts University of Kiel, Kiel, Germany Bacteriophages are recognized DNA vectors and transduction is considered as a common mechanism of lateral gene transfer (LGT) during microbial evolution. Anecdotal events of phage- mediated gene transfer were studied extensively, however, a coherent evolutionary viewpoint of LGT by transduction, its extent and characteristics, is still lacking. Here we report a large-scale evolutionary reconstruction of transduction events in 3982 genomes. We inferred 17 158 recent transduction events linking donors, phages and recipients into a phylogenomic transduction network view. We find that LGT by transduction is mostly restricted to closely related donors and recipients. Furthermore, a substantial number of the transduction events (9%) are best described as gene duplications that are mediated by mobile DNA vectors. We propose to distinguish this type of paralogy by the term autology. A comparison of donor and recipient genomes revealed that genome similarity is a superior predictor of species connectivity in the network in comparison to common habitat. This indicates that genetic similarity, rather than ecological opportunity, is a driver of successful transduction during microbial evolution. A striking difference in the connectivity pattern of donors and recipients shows that while lysogenic interactions are highly species-specific, the host range for lytic phage infections can be much wider, serving to connect dense clusters of closely related species. -

Cell Structure and Function in the Bacteria and Archaea

4 Chapter Preview and Key Concepts 4.1 1.1 DiversityThe Beginnings among theof Microbiology Bacteria and Archaea 1.1. •The BacteriaThe are discovery classified of microorganismsinto several Cell Structure wasmajor dependent phyla. on observations made with 2. theThe microscope Archaea are currently classified into two 2. •major phyla.The emergence of experimental 4.2 Cellscience Shapes provided and Arrangements a means to test long held and Function beliefs and resolve controversies 3. Many bacterial cells have a rod, spherical, or 3. MicroInquiryspiral shape and1: Experimentation are organized into and a specific Scientificellular c arrangement. Inquiry in the Bacteria 4.31.2 AnMicroorganisms Overview to Bacterialand Disease and Transmission Archaeal 4.Cell • StructureEarly epidemiology studies suggested how diseases could be spread and 4. Bacterial and archaeal cells are organized at be controlled the cellular and molecular levels. 5. • Resistance to a disease can come and Archaea 4.4 External Cell Structures from exposure to and recovery from a mild 5.form Pili allowof (or cells a very to attach similar) to surfacesdisease or other cells. 1.3 The Classical Golden Age of Microbiology 6. Flagella provide motility. Our planet has always been in the “Age of Bacteria,” ever since the first 6. (1854-1914) 7. A glycocalyx protects against desiccation, fossils—bacteria of course—were entombed in rocks more than 3 billion 7. • The germ theory was based on the attaches cells to surfaces, and helps observations that different microorganisms years ago. On any possible, reasonable criterion, bacteria are—and always pathogens evade the immune system. have been—the dominant forms of life on Earth. -

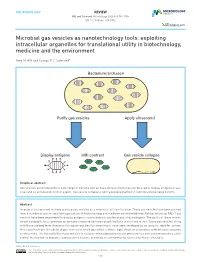

Microbial Gas Vesicles As Nanotechnology Tools: Exploiting Intracellular Organelles for Translational Utility in Biotechnology, Medicine and the Environment

REVIEW Hill and Salmond, Microbiology 2020;166:501–509 DOI 10.1099/mic.0.000912 Microbial gas vesicles as nanotechnology tools: exploiting intracellular organelles for translational utility in biotechnology, medicine and the environment Amy M. Hill and George P. C. Salmond* Bacterium/archaeon Purify gas vesicles Apply ultrasound Display antigens MRI contrast Gas vesicle collapse Graphical abstract Gas vesicles are produced by a wide range of bacteria and archaea. Once purified they can be used to display antigens in vac- cines and as ultrasound contrast agents. Gas vesicle collapse is also a possible method to control cyanobacterial blooms. Abstract A range of bacteria and archaea produce gas vesicles as a means to facilitate flotation. These gas vesicles have been purified from a number of species and their applications in biotechnology and medicine are reviewed here. Halobacterium sp. NRC-1 gas vesicles have been engineered to display antigens from eukaryotic, bacterial and viral pathogens. The ability of these recom- binant nanoparticles to generate an immune response has been quantified both in vitro and in vivo. These gas vesicles, along with those purified from Anabaena flos- aquae and Bacillus megaterium, have been developed as an acoustic reporter system. This system utilizes the ability of gas vesicles to retain gas within a stable, rigid structure to produce contrast upon exposure to ultrasound. The susceptibility of gas vesicles to collapse when exposed to excess pressure has also been proposed as a bio- control mechanism to disperse cyanobacterial blooms, providing an environmental function for these structures. 000912 © 2020 The Authors This is an open- access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License. -

Direct Observation of Protein Secondary Structure in Gas Vesicles by Atomic Force Microscopy

2432 Biophysical Journal Volume 70 May 1996 2432-2436 Direct Observation of Protein Secondary Structure in Gas Vesicles by Atomic Force Microscopy T. J. McMaster,* M. J. Miles,* and A. E. Walsbyt *H. H. Wills Physics Laboratory, and *Department of Botany, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1TL England ABSTRACT The protein that forms the gas vesicle in the cyanobacterium Anabaena flos-aquae has been imaged by atomic force microscopy (AFM) under liquid at room temperature. The protein constitutes "ribs" which, stacked together, form the hollow cylindrical tube and conical end caps of the gas vesicle. By operating the microscope in deflection mode, it has been possible to achieve sub-nanometer resolution of the rib structure. The lateral spacing of the ribs was found to be 4.6 ± 0.1 nm. At higher resolution the ribs are observed to consist of pairs of lines at an angle of -55° to the rib axis, with a repeat distance between each line of 0.57 ± 0.05 nm along the rib axis. These observed dimensions and periodicities are consistent with those determined from previous x-ray diffraction studies, indicating that the protein is arranged in ,B-chains crossing the rib at an angle of 550 to the rib axis. The AFM results confirm the x-ray data and represent the first direct images of a ,3-sheet protein secondary structure using this technique. The orientation of the GvpA protein component of the structure and the extent of this protein across the ribs have been established for the first time. INTRODUCTION Gas vesicle protein and structure Gas vesicles are hollow structures that provide buoyancy in volume of this unit cell, 10.25 nm3, corresponds with that of various aquatic microorganisms. -

Study of the Archaeal Motility System of H. Salinarum by Cryo-Electron Tomography

Technische Universität München Max Planck-Institut für Biochemie Abteilung für Molekulare Strukturbiologie “Study of the archaeal motility system of Halobacterium salinarum by cryo-electron tomography” Daniel Bollschweiler Vollständiger Abdruck der von der Fakultät für Chemie der Technischen Universität München zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Naturwissenschaften genehmigten Dissertation. Vorsitzender: Univ.-Prof. Dr. B. Reif Prüfer der Dissertation: 1. Hon.-Prof. Dr. W. Baumeister 2. Univ.-Prof. Dr. S. Weinkauf Die Dissertation wurde am 05.11.2015 bei der Technischen Universität München eingereicht und durch die Fakultät für Chemie am 08.12.2015 angenommen. “REM AD TRIARIOS REDISSE” - Roman proverb - Table of contents 1. Summary.......................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 3 2.1. Halobacterium salinarum: An archaeal model organism ............................................................ 3 2.1.1. Archaeal flagella ...................................................................................................................... 5 2.1.2. Gas vesicles .............................................................................................................................. 8 2.2. The challenges of high salt media and low dose tolerance in TEM ......................................... -

Cellular Solid-State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy

Cellular solid-state nuclear magnetic SEE COMMENTARY resonance spectroscopy Marie Renaulta, Ria Tommassen-van Boxtelb, Martine P. Bosb, Jan Andries Postc, Jan Tommassenb,1, and Marc Baldusa,1 aBijvoet Center for Biomolecular Research, bDepartment of Molecular Microbiology, Institute of Biomembranes, and cDepartment of Biomolecular Imaging, Institute of Biomembranes, Utrecht University, Padualaan 8, 3584 CH Utrecht, The Netherlands Edited by Robert Tycko, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, and accepted by the Editorial Board January 6, 2012 (received for review October 11, 2011) Decrypting the structure, function, and molecular interactions of conditions (11) as a high-resolution method to investigate atomic complex molecular machines in their cellular context and at atomic structures of major cell-associated (macro)molecules. resolution is of prime importance for understanding fundamental physiological processes. Nuclear magnetic resonance is a well- Results established imaging method that can visualize cellular entities at Sample Design for Cellular ssNMR Spectroscopy. Our goal was to the micrometer scale and can be used to obtain 3D atomic struc- establish general expression and purification procedures that lead 13 15 tures under in vitro conditions. Here, we introduce a solid-state to uniformly C, N-labeled preparations of whole cells (WC) NMR approach that provides atomic level insights into cell-asso- and cell envelopes (CE) containing an arbitrary (membrane) ciated molecular components. By combining dedicated protein pro- protein target (Fig. 1B). As our model system, we selected the duction and labeling schemes with tailored solid-state NMR pulse 150-residue integral membrane-protein PagL from Pseudomonas methods, we obtained structural information of a recombinant aeruginosa, an OM enzyme that removes a fatty acyl chain from integral membrane protein and the major endogenous molecular LPS (12). -

The Transcriptional Activator Gvpe for the Halobacterial Gas Vesicle

Article No. mb981795 J. Mol. Biol. (1998) 279, 761±771 The Transcriptional Activator GvpE for the Halobacterial Gas Vesicle Genes Resembles a Basic Region Leucine-zipper Regulatory Protein Kerstin KruÈ ger1, Thomas Hermann2, Vanessa Armbruster1 and Felicitas Pfeifer1* 1Institut fuÈr Mikrobiologie und The GvpE protein involved in the regulation of gas vesicles synthesis in Genetik, Schnittspahnstr. 10 halophilic archaea has been identi®ed as the transcriptional activator for Technische UniversitaÈt the promoter located upstream of the gvpA gene encoding the major gas Darmstadt, D-64287 vesicle structural protein GvpA. A closer inspection of the GvpE protein Darmstadt, Germany sequence revealed that GvpE resembles basic leucine-zipper proteins typically involved in the gene regulation of eukarya. A molecular model- 2Max-Planck-Institut fuÈr ling study of the C-terminal part implied a cluster of basic amino acid Biochemie, D-82152 residues constituting the DNA-binding site (DNAB) followed by an Martinsried, Germany amphiphilic helix, suitable for the formation of a leucine-zipper structure within a GvpE dimer. The model of a GvpE dimer docked onto DNA indicated that the side-chains of the basic residues could perfectly interact with the negatively charged phosphate groups of the DNA backbone. Substitution of three basic amino acid residues of this putative DNAB by alanine and/or glutamate generated mutated GvpE proteins. None of these was able to activate the c-gvpA promoter in vivo, indicating that these basic residues are required for GvpE activity. This identi®cation of an archaeal gene regulator displaying similarity to eukaryal regulatory proteins implies that the basic transcription machinery of eukarya and archaea are closely related, and that the regulatory proteins have evolved according to common principles. -

Whole‐Genome Comparison Between the Type Strain Of

Received: 17 July 2019 | Revised: 8 November 2019 | Accepted: 9 November 2019 DOI: 10.1002/mbo3.974 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Whole-genome comparison between the type strain of Halobacterium salinarum (DSM 3754T) and the laboratory strains R1 and NRC-1 Friedhelm Pfeiffer1 | Gerald Losensky2 | Anita Marchfelder3 | Bianca Habermann1,4 | Mike Dyall-Smith1,5 1Computational Biology Group, Max-Planck- Institute of Biochemistry, Martinsried, Abstract Germany Halobacterium salinarum is an extremely halophilic archaeon that is widely distributed 2 Microbiology and Archaea, Department of in hypersaline environments and was originally isolated as a spoilage organism of Biology, Technische Universität Darmstadt, T Darmstadt, Germany salted fish and hides. The type strain 91-R6 (DSM 3754 ) has seldom been studied 3Biology II, Ulm University, Ulm, Germany and its genome sequence has only recently been determined by our group. The exact 4 CNRS, IBDM UMR 7288, Aix Marseille relationship between the type strain and two widely used model strains, NRC-1 and Université, Marseille, France R1, has not been described before. The genome of Hbt. salinarum strain 91-R6 consists 5Veterinary Biosciences, Faculty of Veterinary and Agricultural Sciences, of a chromosome (2.17 Mb) and two large plasmids (148 and 102 kb, with 39,230 bp University of Melbourne, Parkville, Vic., being duplicated). Cytosine residues are methylated (m4C) within CTAG motifs. The Australia genomes of type and laboratory strains are closely related, their chromosomes shar- Correspondence ing average nucleotide identity (ANIb) values of 98% and in silico DNA–DNA hy- Friedhelm Pfeiffer, Computational Biology Group, Max-Planck-Institute of bridization (DDH) values of 95%. The chromosomes are completely colinear, do not Biochemistry, Martinsried, Germany. -

Structure of Bacterial and Archaeal Cells

© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION 4 CHAPTER PREVIEW 4.1 There Is Tremendous Diversity Structure of Among the Bacteria and Archaea 4.2 Prokaryotes Can Be Distinguished by Their Cell Shape and Arrangements Bacterial and 4.3 An Overview to Bacterial and Archaeal Cell Structure 4.4 External Cell Structures Interact Archaeal Cells with the Environment Investigating the Microbial World 4: Our planet has always been in the “Age of Bacteria,” ever since the The Role of Pili first fossils—bacteria of course—were entombed in rocks more than TexTbook Case 4: An Outbreak of 3 billion years ago. On any possible, reasonable criterion, bacteria Enterobacter cloacae Associated with a Biofilm are—and always have been—the dominant forms of life on Earth. —Paleontologist Stephen J. Gould (1941–2002) 4.5 Most Bacterial and Archaeal Cells Have a Cell Envelope “Double, double toil and trouble; Fire burn, and cauldron bubble” is 4.6 The Cell Cytoplasm Is Packed the refrain repeated several times by the chanting witches in Shakespeare’s with Internal Structures Macbeth (Act IV, Scene 1). This image of a hot, boiling cauldron actu- MiCroinquiry 4: The Prokaryote/ ally describes the environment in which many bacterial, and especially Eukaryote Model archaeal, species happily grow! For example, some species can be iso- lated from hot springs or the hot, acidic mud pits of volcanic vents ( Figure 4.1 ). When the eminent evolutionary biologist and geologist Stephen J. Gould wrote the opening quote of this chapter, he, as well as most micro- biologists at the time, had no idea that embedded in these “bacteria” was another whole domain of organisms. -

Comparing Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells

Comparing Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells Classification of prokaryotic cellular features: Variant (or NOT common to all) Cell Wall (multiple barrier support themes) Endospores (heavy-duty life support strategy) Bacterial Flagella (appendages for movement) Gas Vesicles (buoyancy compensation devices) Capsules/Slime Layer (exterior to cell wall) Inclusion Bodies (granules for storage) Pili (conduit for genetic exchange) Cell walls of Bacteria Cell envelope structure E. coli structure of peptidoglycan aka murein Peptidoglycan of a gram-positive bacterium Bond broken by penicillin DAP or Diaminopimelic acid Lysine Overall structure of peptidoglycan Cell walls of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria Teichoic acids and the overall structure of the gram-positive cell wall Summary diagram of the gram-positive cell wall Cell envelopes of Bacteria Cell envelopes of Bacteria Structure of the lipopolysaccharide of gram-negative Bacteria The gram-negative cell wall N-Acetyltalosaminuronic acid Pseudopeptidoglycan of Archaea Paracrystalline S-layer: A protein jacket for Bacteria & Archaea Formation of the endospore Morphology of the bacterial endospore (a) Terminal (b) Subterminal (c) Central (a) Structure of Dipicolinic Acid & (b) crosslinked with Ca++ Bacterial flagella (a) Polar (aka monotrichous) & (b) Peritrichous Structure of the bacterial flagellum Flagellar Motility: Relationship of flagellar rotation to bacterial movement. Gas Vesicles (a) Anabaena flos-aquae (b) Microcystis sp. Hammer & Stopper Experiment (Before) (After) Model of how the two proteins that make up the gas vesicle, GvpA and GvpC, interact to form a watertight but gas-permeable structure. β-sheet α-helix Bacterial Capsules (a) Acinetobacter sp. (b) Rhizobium trifolii negative stain Storage of PHB Sulfur globules inside the purple sulfur bacterium Isochromatium buderi Magnetotactic bacteria with Fe3O4 (magnetite) particles called magnetosomes EM of Salmonella typhi “Sex” Pili used in bacterial conjugation of E.