Technical Presentation Abstracts by Session

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Report: 2019 Western Snowy Plover Breeding in Coastal Northern California, Recovery Unit 2

Final Report: 2019 Western Snowy Plover Breeding in Coastal Northern California, Recovery Unit 2 E.J. Feucht1, M.A. Colwell1, K.M. Raby1, J.A. Windsor1, and S.E. McAllister2 1 Wildlife Department, Humboldt State University, Arcata, CA 95521 2 6104 Beechwood Drive, Eureka, CA 95503 Abstract.—In 1993, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service listed the Pacific coast population of the Western Snowy Plover (Charadrius nivosus nivosus) as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. For the 19th consecutive year, we monitored plovers in Del Norte, Humboldt, and Mendocino counties in northern California (designated Recovery Unit 2 [RU2]). In this report, we summarize results from the 2019 breeding season and present a preliminary analysis on apparent survival of the local population using 19 years of mark-recapture data. In 2019, 72 adults (34 males, 38 females) bred in RU2, a 14% increase from 2018 and 48% of the recovery objective. First-time breeders made up 35-44% of the population, including 10-17 immigrants and 15 philopatric birds. Plovers nested on seven beaches (six in Humboldt and one in Mendocino) and fledged chicks at five locations. The sites with the most breeding plovers were South Spit of Humboldt Bay (n=30) and Centerville Beach (n=15). In total, plovers initiated 75 nests, hatched 100 chicks, and fledged 58 juveniles. For the fourth consecutive year, South Spit was the most productive site with 72% hatching success (23 of 32 nests) and 59% fledging success (37 of 63 chicks). Fledglings from South Spit made up 64% of the RU2 cohort, a percentage that has increased approximately 10% each year since 2016. -

OF DEL NORTE COUNTY ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICE 981 "H" Street, Suite 210 Crescent City, California 95531

COUNTY OF DEL NORTE COUNTY ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICE 981 "H" Street, Suite 210 Crescent City, California 95531 Phone Fax (707) 464-7214 (707) 464-1165 DEL NORTE COUNTY BOARD REPORT DATE: 4/5/07 AGENDA DATE : 4/10/07 TO: DEL NORTE COUNTY BOARD OF SUPERVISORS ORIGINATING DEPARTMENT: Administration CONTACT PERSON : Jay Sarina, Assistant County Administrative Officer SUBJECT: Response to Blue Ribbon Coalition Request Letter RECOMMENDATION: Discuss possible action as requested by the Blue Ribbon Coalition as it relates to Tolowa Dunes State Park and associated access restrictions. Direct staff to assist as needed. DISCUSSION /JUSTIFICATION: Del Norte County has previously corresponded with California State Parks over Off-Highway Vehicle access restrictions imposed on land adjacent to and within Tolowa State Park without adequate public due process. The board of Supervisors previously requested State Parks reopen the issue and propose a specific format for the suggested community dialogue. The California Department of Parks and Recreation replied to that request nine months later and has indicated that they feel their staff took adequate steps to invite public discourse on the issue. No additional action was proposed. The Blue Ribbon Coalition has requested the County take appropriate formal action in support of recreationists to address issues at Tolowa dunes State Park and Kellogg beach. The Del Norte County Board of Supervisors has taken steps to reopen the issue and involve the public with no cooperation from State Parks. "Preserving Our Natural Resources FOR The Public Instead Of FROM The Public" April 5, 2007 (Sent via US Mail and Electronic Transmission) Supervisor Gerry Hemmingsen Del Norte County Board of Supervisors 981 H Street Crescent City, CA 95531 Re: Tolowa Dunes/Kellogg Beach Dear Supervisor Hemmingsen: Please accept this communiqu6 from the BlueRibbon Coalition (BRC) as an official request to the Del Norte County Board of Supervisors that they take the appropriate formal action and direct staff to address access issues at Tolowa Dunes and Kellogg Beach. -

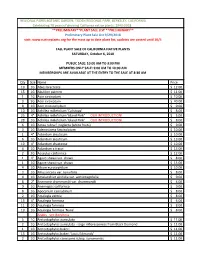

Qty Size Name Price 10 1G Abies Bracteata 12.00 $ 15 1G Abutilon

REGIONAL PARKS BOTANIC GARDEN, TILDEN REGIONAL PARK, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA Celebrating 78 years of growing California native plants: 1940-2018 **PRELIMINARY**PLANT SALE LIST **PRELIMINARY** Preliminary Plant Sale List 9/29/2018 visit: www.nativeplants.org for the most up to date plant list, updates are posted until 10/5 FALL PLANT SALE OF CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANTS SATURDAY, October 6, 2018 PUBLIC SALE: 10:00 AM TO 3:00 PM MEMBERS ONLY SALE: 9:00 AM TO 10:00 AM MEMBERSHIPS ARE AVAILABLE AT THE ENTRY TO THE SALE AT 8:30 AM Qty Size Name Price 10 1G Abies bracteata $ 12.00 15 1G Abutilon palmeri $ 11.00 1 1G Acer circinatum $ 10.00 3 5G Acer circinatum $ 40.00 8 1G Acer macrophyllum $ 9.00 10 1G Achillea millefolium 'Calistoga' $ 8.00 25 4" Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' OUR INTRODUCTION! $ 5.00 28 1G Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' OUR INTRODUCTION! $ 8.00 6 1G Actea rubra f. neglecta (white fruits) $ 9.00 3 1G Adenostoma fasciculatum $ 10.00 1 4" Adiantum aleuticum $ 10.00 6 1G Adiantum aleuticum $ 13.00 10 4" Adiantum shastense $ 10.00 4 1G Adiantum x tracyi $ 13.00 2 2G Aesculus californica $ 12.00 1 4" Agave shawii var. shawii $ 8.00 1 1G Agave shawii var. shawii $ 15.00 4 1G Allium eurotophilum $ 10.00 3 1G Alnus incana var. tenuifolia $ 8.00 4 1G Amelanchier alnifolia var. semiintegrifolia $ 9.00 8 2" Anemone drummondii var. drummondii $ 4.00 9 1G Anemopsis californica $ 9.00 8 1G Apocynum cannabinum $ 8.00 2 1G Aquilegia eximia $ 8.00 15 4" Aquilegia formosa $ 6.00 11 1G Aquilegia formosa $ 8.00 10 1G Aquilegia formosa 'Nana' $ 8.00 Arabis - see Boechera 5 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata $ 11.00 2 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata - large inflorescences from Black Diamond $ 11.00 1 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri $ 11.00 15 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri 'Louis Edmunds' $ 11.00 2 1G Arctostaphylos canescens subsp. -

Arctostaphylos Hispidula, Gasquet Manzanita

Conservation Assessment for Gasquet Manzanita (Arctostaphylos hispidula) Within the State of Oregon Photo by Clint Emerson March 2010 U.S.D.A. Forest Service Region 6 and U.S.D.I. Bureau of Land Management Interagency Special Status and Sensitive Species Program Author CLINT EMERSON is a botanist, USDA Forest Service, Rogue River-Siskiyou National Forest, Gold Beach and Powers Ranger District, Gold Beach, OR 97465 TABLE OF CONTENTS Disclaimer 3 Executive Summary 3 List of Tables and Figures 5 I. Introduction 6 A. Goal 6 B. Scope 6 C. Management Status 7 II. Classification and Description 8 A. Nomenclature and Taxonomy 8 B. Species Description 9 C. Regional Differences 9 D. Similar Species 10 III. Biology and Ecology 14 A. Life History and Reproductive Biology 14 B. Range, Distribution, and Abundance 16 C. Population Trends and Demography 19 D. Habitat 21 E. Ecological Considerations 25 IV. Conservation 26 A. Conservation Threats 26 B. Conservation Status 28 C. Known Management Approaches 32 D. Management Considerations 33 V. Research, Inventory, and Monitoring Opportunities 35 Definitions of Terms Used (Glossary) 39 Acknowledgements 41 References 42 Appendix A. Table of Known Sites in Oregon 45 2 Disclaimer This Conservation Assessment was prepared to compile existing published and unpublished information for the rare vascular plant Gasquet manzanita (Arctostaphylos hispidula) as well as include observational field data gathered during the 2008 field season. This Assessment does not represent a management decision by the U.S. Forest Service (Region 6) or Oregon/Washington BLM. Although the best scientific information available was used and subject experts were consulted in preparation of this document, it is expected that new information will arise. -

Adenostoma Fasciculatum (Chamise), Arctostaphylos Canescens (Hoary Manzanita), and Arctostaphylos Virgata (Marin Manzanita) Alison S

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Master's Projects and Capstones Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects 5-20-2016 Preserving Biodiversity for a Climate Change Future: A Resilience Assessment of Three Bay Area Species--Adenostoma fasciculatum (Chamise), Arctostaphylos canescens (Hoary Manzanita), and Arctostaphylos virgata (Marin Manzanita) Alison S. Pollack University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Biology Commons, Botany Commons, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, and the Other Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Pollack, Alison S., "Preserving Biodiversity for a Climate Change Future: A Resilience Assessment of Three Bay Area Species-- Adenostoma fasciculatum (Chamise), Arctostaphylos canescens (Hoary Manzanita), and Arctostaphylos virgata (Marin Manzanita)" (2016). Master's Projects and Capstones. 352. https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone/352 This Project/Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Projects and Capstones by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 This Master's Project Preserving Biodiversity for a Climate Change Future: A Resilience Assessment of Three Bay Area Species--Adenostoma fasciculatum (Chamise), Arctostaphylos canescens (Hoary Manzanita), and Arctostaphylos virgata (Marin Manzanita) by Alison S. Pollack is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Science in Environmental Management at the University of San Francisco Submitted: Received: ................................…………. -

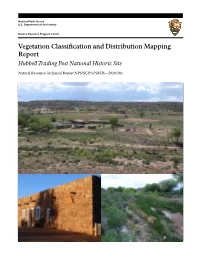

Vegetation Classification and Distribution Mapping Report: Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Vegetation Classification and Distribution Mapping Report Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SCPN/NRTR—2010/301 ON THE COVER Top: Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site as seen from Hubbell Hill; photo by Courtney White, www.awestthatworks.com. Bottom left: Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site; photo by Stephen Monroe. Bottom right: Hubbell Wash, photo by Stephen Monroe. Vegetation Classification and Distribution Mapping Report Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SCPN/NRTR—2010/301 Authors David Salas Corey Bolen Bureau of Reclamation Remote Sensing and GIS Group Mail Code 86-68211 Denver Federal Center Building 67 Denver, Colorado 80225 Project Manager Anne Cully National Park Service, Southern Colorado Plateau Network P.O. Box 5765 Northern Arizona University Flagstaff, Arizona 86011 Editing and Design Jean Palumbo National Park Service, Southern Colorado Plateau Network P.O. Box 5765 Northern Arizona University Flagstaff, Arizona 86011 March 2010 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Program Center publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituen cies, and the public. The Natural Resource Technical Report Series is used to disseminate results of scientific studies in the physical, biological, and social sciences for both the advancement of science and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. -

California State Parks Gathering Pamphlet

State Park Units of the North Coast Redwoods District: State Parks Mission Native California Indian Traditional Gathering Del Norte County: Pelican State Beach Tolowa Dunes State Park Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park Del Norte Coast Redwoods State Park Humboldt County: Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park Humboldt Lagoons State Park In the Harry A. Merlo State Recreation Area Patrick’s Point State Park North Coast Redwoods Trinidad State Beach Little River State Beach District Azalea State Natural Reserve of California State Parks Fort Humboldt State Historic Park Grizzly Creek Redwoods State Park Humboldt Redwoods State Park John B. Dewitt Redwoods State Natural Reserve Benbow State Recreation Area Richardson Grove State Park Mendocino County: Reynolds Wayside Campground Smithe Redwoods State Reserve Standish-Hickey State Recreation Area Sinkyone Wilderness State Park Admiral William Standley State Recreation Area Gathering Permits THE PURPOSE OF THE GATHERING PERMIT IS TO FOSTER CULTURAL CONTINUITY AND TO PRESERVE AND California State Parks recognizes its To obtain a Gathering Permit for park INTERPRET CALIFORNIA’S CULTURAL special responsibility as the steward of units in the North Coast Redwoods TRADITIONS. many areas of cultural and spiritual District, contact: The public benefits each and every significance to living Native peoples of time a California Indian makes a California. Greg Collins, M.A., RPA basket or continues any other cultural tradition since the action Cultural Resources Program Manager helps perpetuate the tradition. California State Parks issues Native North Coast Redwoods District THE RAW MATERIALS COLLECTED California Indian Gathering Permits California State Parks MUST BE USED FOR HERITAGE (DPR 864) to collect materials in units (707) 445-6547 x35 PRESERVATION AND MAY NOT BE USED FOR COMMERCIAL PROFIT. -

Historical Shoreline Analysis for Humboldt Bay, California

Historical Shoreline Analysis For Humboldt Bay, California Shoreline Change along Coastal Dunes from Table Bluff to Trinidad, 1939-2016 Kelsey McDonald October 10, 2017 Summary The Historical Shoreline Analysis provides information on long-term trends in shoreline movement to support understanding of coastal change along dune systems within the Eureka littoral cell. The study is a component of the Dunes Climate Ready project, which seeks to understand how sea level rise will impact dune systems and how land managers can promote adaptation. Shorelines digitally traced from aerial imagery dating 1939 to 2016 revealed varying patterns of erosion and accretion across dune-backed shorelines of the Humboldt Bay area. The ArcGIS plugin Digital Shoreline Analysis System (DSAS) analyzed shoreline change along digital transects to provide linear regression rates of shoreline change over the study period. Most of the sandy shorelines around Humboldt Bay are stable to prograding, with the exception of the North Jetty area. The beach at the North Jetty has been eroding rapidly since 1939 (2.08 ± 0.16 m/year). The North Spit from Samoa to Mad River Beach has been stable to accreting (no significant change to less than 1m/year). The Clam Beach to Little River shoreline stretch has shown high accretion (2.56 ± 0.15 m/year). The South Spit has shown moderate accretion (1.27 ± 0.06 m/year). The long-term rates of change provide historical reference for monitoring coastal responses to sea level rise and climate events. 1 Introduction The Historical Shoreline Analysis is a component of the Dunes Climate Ready Study, which seeks to provide information on patterns of sediment movement within the Eureka littoral cell and identify potential coastal vulnerabilities and responses to sea level rise and other aspects of climate change. -

Phylogenies and Secondary Chemistry in Arnica (Asteraceae)

Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Science and Technology 392 Phylogenies and Secondary Chemistry in Arnica (Asteraceae) CATARINA EKENÄS ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS ISSN 1651-6214 UPPSALA ISBN 978-91-554-7092-0 2008 urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-8459 !"# $ % !& '((" !()(( * * * + , - . , / , '((", + 0 1# 2, # , 34', 56 , , 70 46"84!855&86(4'8(, - 1# 2 . * 9 10-2 . * . # 9 , * * 1 ! " #! !$ 2 1 2 .8 # * * :# 77 1%&'(2 . !6 '3, + . .8 ) / , ; < * . * ** # , * * * , 09 * . # * * 33 * != , 0- # 9 * * 1, , * 2 . * , 0 * * * * * . * , $ * 0- * % # , # 8 * * * * * * $8> # . * * !' , * * . ** , ? . 0- , +,- # # 7-0 -0 :+' 9 +# $8> ./0) . ) 1 ) 2 * 3) ) .456(7 ) , @ / '((" 700 !=5!8='!& 70 46"84!855&86(4'8( ) ))) 8"&54 1 );; ,/,; A B ) ))) 8"&542 List of Papers This thesis is based on the following papers, which are referred to in the text by their Roman numerals: I Ekenäs, C., B. G. Baldwin, and K. Andreasen. 2007. A molecular phylogenetic -

Vascular Plants of Eagle Creek Campground, Trinity County

Humboldt State University Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University Botanical Studies Open Educational Resources and Data 9-17-2018 Vascular Plants of Eagle Creek Campground, Trinity County James P. Smith Jr Humboldt State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Smith, James P. Jr, "Vascular Plants of Eagle Creek Campground, Trinity County" (2018). Botanical Studies. 84. https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps/84 This Flora of Northwest California-Checklists of Local Sites is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Educational Resources and Data at Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Botanical Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE VASCULAR PLANTS OF EAGLE CREEK CAMPGROUND (TRINITY COUNTY, CALIFORNIA) Compiled by James P. Smith, Jr. Professor Emeritus of Botany Department of Biological Sciences Humboldt State University Fifth Edition • 14 September 2018 The Eagle Creek Campground is located about Boraginaceae five miles north of Coffee Creek along State Route Amsinckia intermedia 3 in the Shasta-Trinity National Forest. On one Lithospermum californicum side is the Trinity River and Eagle Creek on the Plagiobothrys tenellus other. Caryophyllaceae F E R N S Eremogone congesta Silene lemmonii Equisetum hyemale var. affine Stellaria media Cheilanthes siliquosa Stellaria nitens Polystichum imbricans ssp. imbricans Pteridium aquilinum var. pubescens Compositae (Asteraceae) Adenocaulon bicolor C O N I F E R S Ageratina occidentale Agoseris heterophylla Abies concolor Antennaria argentea Calocedrus decurrens Antennaria dimorpha Pinus jeffreyi Balsamorhiza deltoidea Pinus ponderosa var. -

Washington Flora Checklist a Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Washington State Hosted by the University of Washington Herbarium

Washington Flora Checklist A checklist of the Vascular Plants of Washington State Hosted by the University of Washington Herbarium The Washington Flora Checklist aims to be a complete list of the native and naturalized vascular plants of Washington State, with current classifications, nomenclature and synonymy. The checklist currently contains 3,929 terminal taxa (species, subspecies, and varieties). Taxa included in the checklist: * Native taxa whether extant, extirpated, or extinct. * Exotic taxa that are naturalized, escaped from cultivation, or persisting wild. * Waifs (e.g., ballast plants, escaped crop plants) and other scarcely collected exotics. * Interspecific hybrids that are frequent or self-maintaining. * Some unnamed taxa in the process of being described. Family classifications follow APG IV for angiosperms, PPG I (J. Syst. Evol. 54:563?603. 2016.) for pteridophytes, and Christenhusz et al. (Phytotaxa 19:55?70. 2011.) for gymnosperms, with a few exceptions. Nomenclature and synonymy at the rank of genus and below follows the 2nd Edition of the Flora of the Pacific Northwest except where superceded by new information. Accepted names are indicated with blue font; synonyms with black font. Native species and infraspecies are marked with boldface font. Please note: This is a working checklist, continuously updated. Use it at your discretion. Created from the Washington Flora Checklist Database on September 17th, 2018 at 9:47pm PST. Available online at http://biology.burke.washington.edu/waflora/checklist.php Comments and questions should be addressed to the checklist administrators: David Giblin ([email protected]) Peter Zika ([email protected]) Suggested citation: Weinmann, F., P.F. Zika, D.E. Giblin, B. -

Sensitive Species That Are Not Listed Or Proposed Under the ESA Sorted By: Major Group, Subgroup, NS Sci

Forest Service Sensitive Species that are not listed or proposed under the ESA Sorted by: Major Group, Subgroup, NS Sci. Name; Legend: Page 94 REGION 10 REGION 1 REGION 2 REGION 3 REGION 4 REGION 5 REGION 6 REGION 8 REGION 9 ALTERNATE NATURESERVE PRIMARY MAJOR SUB- U.S. N U.S. 2005 NATURESERVE SCIENTIFIC NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME(S) COMMON NAME GROUP GROUP G RANK RANK ESA C 9 Anahita punctulata Southeastern Wandering Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G4 NNR 9 Apochthonius indianensis A Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1G2 N1N2 9 Apochthonius paucispinosus Dry Fork Valley Cave Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 Pseudoscorpion 9 Erebomaster flavescens A Cave Obligate Harvestman Invertebrate Arachnid G3G4 N3N4 9 Hesperochernes mirabilis Cave Psuedoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G5 N5 8 Hypochilus coylei A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G3? NNR 8 Hypochilus sheari A Lampshade Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2G3 NNR 9 Kleptochthonius griseomanus An Indiana Cave Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 8 Kleptochthonius orpheus Orpheus Cave Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 9 Kleptochthonius packardi A Cave Obligate Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G2G3 N2N3 9 Nesticus carteri A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid GNR NNR 8 Nesticus cooperi Lost Nantahala Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 8 Nesticus crosbyi A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G1? NNR 8 Nesticus mimus A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2 NNR 8 Nesticus sheari A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2? NNR 8 Nesticus silvanus A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2? NNR