Rhetoric and Time: Cognition, Culture, and Interaction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Motor Selection Dynamics in FEF Explain the Reaction Time Variance of Saccades to Single Targets

RESEARCH ARTICLE Motor selection dynamics in FEF explain the reaction time variance of saccades to single targets Christopher K Hauser, Dantong Zhu, Terrence R Stanford, Emilio Salinas* Department of Neurobiology and Anatomy, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, United States Abstract In studies of voluntary movement, a most elemental quantity is the reaction time (RT) between the onset of a visual stimulus and a saccade toward it. However, this RT demonstrates extremely high variability which, in spite of extensive research, remains unexplained. It is well established that, when a visual target appears, oculomotor activity gradually builds up until a critical level is reached, at which point a saccade is triggered. Here, based on computational work and single-neuron recordings from monkey frontal eye field (FEF), we show that this rise-to- threshold process starts from a dynamic initial state that already contains other incipient, internally driven motor plans, which compete with the target-driven activity to varying degrees. The ensuing conflict resolution process, which manifests in subtle covariations between baseline activity, build- up rate, and threshold, consists of fundamentally deterministic interactions, and explains the observed RT distributions while invoking only a small amount of intrinsic randomness. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.33456.001 Introduction The reaction time (RT) represents the total time taken to perform all of the mental operations that may contribute to a particular action, such as stimulus detection, attention, working memory, or motor preparation. Although the importance of the RT as a fundamental metric for inferring the *For correspondence: mechanisms that mediate cognition cannot be overstated (Welford, 1980; Meyer et al., 1988), [email protected] such reliance is a double-edged sword. -

A Visualization on What's Changing Google Accounts Help

Google Accounts Help About the conversion: A visualization on what's changing Google offers different types of accounts to different types of users. Until recently, we offered two primary types of accounts that were completely separate services: Google Accounts Provide access to all Google products and services, such as Gmail, Blogger, Orkut, and Web History. Can be created with any email address, such as the email address you have with your organization, or with any webmail address (@yahoo.com, @hotmail.com, etc.). Signing up for Gmail automatically creates a Google Account with that address. Google Apps Accounts Issued and managed by and used with your @my-domain.com organization. Provide access to only Gmail, Calendar, Docs, Sites, Groups, and Video. Before the transition Google Accounts Google Apps accounts Example accounts: [email protected] Example accounts: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Sample of products on Google Accounts: Only 6 products on Google Apps accounts: However, we recently transitioned Google Apps accounts so you can use your @my-domain.com address to access the same Google products and services that Google Accounts holders can. Your Google Apps Account is now a Google Account. Conflicting accounts If you've used other Google products outside of the ones you can access with your Google Apps account such as Picasa, Reader, or AdWords, you've already created a conflicting Google Account. If you used your Google Apps email address to sign up for and use those other Google services, you now have two Google Accounts, with the same address. -

Timing Accuracy of Web Applications on Touchscreen and Keyboard Devices

Behavior Research Methods https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-019-01321-2 Mental chronometry in the pocket? Timing accuracy of web applications on touchscreen and keyboard devices Thomas Pronk1,2 & Reinout W. Wiers1 & Bert Molenkamp1,2 & Jaap Murre1 # The Author(s) 2020 Abstract Web applications can implement procedures for studying the speed of mental processes (mental chronometry) and can be administered via web browsers on most commodity desktops, laptops, smartphones, and tablets. This approach to conducting mental chronometry offers various opportunities, such as increased scale, ease of data collection, and access to specific samples. However, validity and reliability may be threatened by less accurate timing than specialized software and hardware can offer. We examined how accurately web applications time stimuli and register response times (RTs) on commodity touchscreen and keyboard devices running a range of popular web browsers. Additionally, we explored the accuracy of a range of technical innovations for timing stimuli, presenting stimuli, and estimating stimulus duration. The results offer some guidelines as to what methods may be most accurate and what mental chronometry paradigms may suitably be administered via web applications. In controlled circumstances, as can be realized in a lab setting, very accurate stimulus timing and moderately accurate RT mea- surements could be achieved on both touchscreen and keyboard devices, though RTs were consistently overestimated. In uncontrolled circumstances, such as researchers may encounter online, stimulus presentation may be less accurate, especially when brief durations are requested (of up to 100 ms). Differences in RT overestimation between devices might not substantially affect the reliability with which group differences can be found, but they may affect reliability for individual differences. -

Sanatana-Dharma

BASICS OF SANATANA DHARMA YUGAS • Satya Yuga (also known as Krita Yuga "Golden Age"): • The first and best Yuga. It was the age of truth and perfection. • Humans were gigantic, powerfully built, handsome, honest, youthful, vigorous, erudite and virtuous. The Vedas were one. All mankind could attain to supreme blessedness. • There was no agriculture or mining as the earth yielded those riches on its own. • Weather was pleasant and everyone was happy. There were no religious sects. There was no disease, decrepitude or fear of anything. • Human lifespan was 100,000 years and humans tended to have hundreds or thousands of sons or daughters. • People had to perform penances for thousands of years to acquire Samadhi and die. • Matsya, Kurma, Varaha and Narasimha are the four avatars of Vishnu in this yuga. • Treta Yuga: • Is considered to be the second Yuga in order, however Treta means the "Third". • In this age, virtue diminishes slightly. • At the beginning of the age, many emperors rise to dominance and conquer the world. Wars become frequent and weather begins to change to extremities. • Oceans and deserts are formed. • People become slightly diminished compared to their predecessors. • Agriculture, labor and mining become existent. Average lifespan of humans is around 1000- 10,000 years. • Vamana, ParasuRama, and Sri RamaChandra are the three avatars of Vishnu in Treta Yuga. • Dvapara Yuga: • Is considered to be the third Yuga in order. • Dvapara means "two pair" or "after two". • In this age, people become tainted with Tamasic qualities and aren't as strong as their ancestors. • Diseases become rampant. -

Google Apps: an Introduction to Picasa

[Not for Circulation] Google Apps: An Introduction to Picasa This document provides an introduction to using Picasa, a free application provided by Google. With Picasa, users are able to add, organize, edit, and share their personal photos, utilizing 1 GB of free space. In order to use Picasa, users need to create a Google Account. Creating a Google Account To create a Google Account, 1. Go to http://www.google.com/. 2. At the top of the screen, select “Gmail”. 3. On the Gmail homepage, click on the right of the screen on the button that is labeled “Create an account”. 4. In order to create an account, you will be asked to fill out information, including choosing a Login name which will serve as your [email protected], as well as a password. After completing all the information, click “I accept. Create my account.” at the bottom of the page. 5. After you successfully fill out all required information, your account will be created. Click on the “Show me my account” button which will direct you to your Gmail homepage. Downloading Picasa To download Picasa, go http://picasa.google.com. 1. Select Download Picasa. 2. Select Save File. Information Technology Services, UIS 1 [Not for Circulation] 3. Click on the downloaded file, and select Run. 4. Follow the installation procedures to complete the installation of Picasa on your computer. When finished, you will be directed to a new screen. Click Get Started with Picasa Web Albums. Importing Pictures Photos can be uploaded into Picasa a variety of ways, all of them very simple to use. -

Governance and Leadership

Dr. Vaishnavanghri Sevaka Das, Ph.D. Director, Bhaktivedanta College of Vedic Education Affiliated to ISKCON, Navi Mumbai 1 Governance and Leadership Governance “the action or manner of governing a state, organization, etc. for enhancing prosperity and sustenance” Leadership “the state or position of being a leader for ensuring the good Governance” 2 Four Yugas and Yuga Chakra Our Position (Fixed) Kali Yuga Dwapara Yuga 4,32,000 Years 8,64,000 Years 10% 20% 1 Yuga Chakra 43,20,000 Years 40% 30% Satya Yuga Treta Yuga 17,28,000 Years 12,96,000 Years 1000 Rotations of the Yuga Chakra = 1 Day of Brahma Ji 1000 Rotations of the Yuga Chakra = 1 Night of Brahma Ji 3 Concept of Four Quotients Spiritually Intellectually Strong Sharp Physically Mentally Fit Balanced 4 Test Your Understanding of the Four Quotients • Rakesh is getting ready for his final semester exam. Because of his night out he is weak and tensed. • Rakesh’s father Rajaram came from morning jogging with heavy sweating and comforted his son with inspirational words. • Rakesh’s mother Shanti did special prayers to Lord Ganesha for all success to her son but she is also very tensed. • Rakesh’s sister Rakhi gave best wishes to him and put a tilak. She reminded him of his strengths and also warned him of weakness of getting nervous. • Rakesh got onto his bike and started speeding towards his college. He is tensed as his thoughts were also speeding on top gear. • Rakesh stopped on the road when he saw his classmate Abhay with whom he never spoke. -

SIC Bibliography 17

Scientific Instrument Commission Bibliography 17 Seventeenth bibliography of books, pamphlets, catalogues, articles on or connected with historical scientific instruments. This bibliography covers the year 2000, but also contains earlier publications which only came to the compiler's notice after publication of the Sixteenth Bibliography in June 2000. The compiler wishes to thank those who sent titles for inclusion in this bibliography. Publications, or notices of publication (please with ISBN) for the forthcoming bibliography, covering the year 2001, may be sent to: Dr. P.R. de Clercq Secretary of the Scientific Instrument Commission 13 Camden Square London NW1 9UY United Kingdom E-mail: [email protected] ABGRALL, P., 'La géometrie de l'astrolabe au Xe siècle', Arabic Sciences and Philosophy 10 (March 2000), 7-78 AKPAN, Eloise, The story of William Stanley: a self-made man (London: published by the author, 2000). 128 pages, illustrated. Available from the author at [email protected] Stanley was a scientific instrument-maker, but also engaged in many other activities, described in this book. ALDINGER, Henry and CHAMBERLAIN, Ed, 'Gilson Slide Rules - Part I - The Small Rules' and 'Gilson Slide Rules - Part II - The Large Rules', Journal of the Oughtred Society 9, nr. 1 (Spring 2000), 48-60 and nr. 2 (Fall 2000), 47-58. The Gilson Slide Rule Co. was formed by Claire Gilson in Michigan in 1915. ARIVALDI, Mario, 'Medieval monastic sundials with six sectors: an investigation into their origins and meaning', British Sundial Society Bulletin 12 (2000), 109-115 BAGIOLI, Mario, 'Replication or Monopoly? The Economies of Invention and Discovery in Galileo's Observations of 1610', Science in Context 13, vol. -

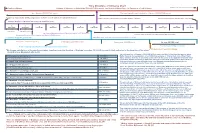

Time Structure of Universe Chart

Time Structure of Universe Chart Creation of Universe Lifespan of Universe - 1 Maha Kalpa (311.040 Trillion years, One Breath of Maha-Visnu - An Expansion of Lord Krishna) Complete destruction of Universe Age of Universe: 155.52197 Trillion years Time remaining until complete destruction of Universe: 155.51803 Trillion years At beginning of Brahma's day, all living beings become manifest from the unmanifest state (Bhagavad-Gita 8.18) 1st day of Brahma in his 51st year (current time position of Brahma) When night falls, all living beings become unmanifest 1 Kalpa (Daytime of Brahma, 12 hours)=4.32 Billion years 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas 1 Manvantara 306.72 Million years Age of current Manvantara and current Manu (Vaivasvata): 120.533 Million years Time remaining for current day of Brahma: 2.347051 Billion years Between each Manvantara there is a juncture (sandhya) of 1.728 Million years 1 Chaturyuga (4 yugas)=4.32 Million years 28th Chaturyuga of the 7th manvantara (current time position) Satya-yuga (1.728 million years) Treta-yuga (1.296 million years) Dvapara-yuga (864,000 years) Kali-yuga (432,000 years) Time remaining for Kali-yuga: 427,000 years At end of each yuga and at the start of a new yuga, there is a juncture period 5000 years (current time position in Kali-yuga) "By human calculation, a thousand ages taken together form the duration of Brahma's one day [4.32 billion years]. -

Getting Started with Google Cloud Platform

Harvard AP275 Computational Design of Materials Spring 2018 Boris Kozinsky Getting started with Google Cloud Platform A virtual machine image containing Python3 and compiled LAMMPS and Quantum Espresso codes are available for our course on the Google Cloud Platform (GCP). Below are instructions on how to get access and start using these resources. Request a coupon code: Google has generously granted a number of free credits for using GCP Compute Engines. Here is the URL you will need to access in order to request a Google Cloud Platform coupon. You will be asked to provide your school email address and name. An email will be sent to you to confirm these details before a coupon code is sent to you. Student Coupon Retrieval Link • You will be asked for a name and email address, which needs to match the domain (@harvard.edu or @mit.edu). A confirmation email will be sent to you with a coupon code. • You can only request ONE code per unique email address. If you run out of computational resources, Google will grant more coupons! If you don’t have a Gmail account, please get one. Harvard is a subscriber to G Suite, so access should work with your @g.harvard.edu email and these were added already to the GCP project. If you prefer to use your personal Gmail login, send it to me. Once you have your google account, you can log in and go to the website below to redeem the coupon. This will allow you to set up your GCP billing account. -

Digital Media Asset Management and Sharing

Digital Media Asset Management and Sharing Introduction Digital media is one of the fastest growing areas on the internet. According to a market study by Informa Telecoms & Media conducted in 2012, the global 1. online video market only, will reach $37 billion in 2017¹. Other common media OTT Video Revenue Forecasts, types include images, music, and digital documents. One driving force for this 2011-2017, by Informa Telecoms phenomena growth is the popularity of feature rich mobile devices2, equipped & Media, with higher resolution cameras, bigger screens, and faster data connections. November 2012. This has led to a massive increase in media content production and con- sumption. Another driving force is the trend among many social networks to 2. incorporate media sharing as a core feature in their systems². Meanwhile, Key trends and Takeaways in Digital numerous startup companies are trying to build their own niche areas in Media Market, this market. by Abhay Paliwal, March 2012. This paper will use an example scenario to provide a technical deep-dive on how to use Google Cloud Platform to build a digital media asset management and sharing system. Example Scenario - Photofeed Photofeed, a fictitious start-up company, is interested in building a photo sharing application that allows users to upload and share photos with each other. This application also includes a social aspect and allows people to post comments about photos. Photofeed’s product team believes that in order for them to be competitive in this space, users must be able to upload, view, and edit photos quickly, securely and with great user experiences. -

The Psychophysiology of Novelty Processing

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School January 2013 The syP chophysiology of Novelty Processing: Do Brain Responses to Deviance Predict Recall, Recognition and Response Time? Siri-Maria Kamp University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Biological Psychology Commons Scholar Commons Citation Kamp, Siri-Maria, "The sP ychophysiology of Novelty Processing: Do Brain Responses to Deviance Predict Recall, Recognition and Response Time?" (2013). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/4703 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Psychophysiology of Novelty Processing: Do Brain Responses to Deviance Predict Recall, Recognition, and Response Time? by Siri-Maria Kamp A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Psychology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Emanuel Donchin, Ph.D. Yael Arbel, Ph.D. Kenneth J. Malmberg, Ph.D. Geoffrey F. Potts, Ph.D. Kristen Salomon, Ph.D Date of Approval: July 11, 2013 Keywords: Event-related potentials, pupillometry, P300, Novelty P3, oddball paradigm Copyright © 2013, Siri-Maria Kamp -

Jon Leibowitz, Chairman J. Thomas Rosch Edith Ramirez Julie Brill

102 3136 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION COMMISSIONERS: Jon Leibowitz, Chairman J. Thomas Rosch Edith Ramirez Julie Brill ____________________________________ ) In the Matter of ) ) GOOGLE INC., ) a corporation. ) DOCKET NO. C-4336 ____________________________________) COMPLAINT The Federal Trade Commission, having reason to believe that Google Inc. (“Google” or “respondent”), a corporation, has violated the Federal Trade Commission Act (“FTC Act”), and it appearing to the Commission that this proceeding is in the public interest, alleges: 1. Respondent Google is a Delaware corporation with its principal office or place of business at 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043. 2. The acts and practices of respondent as alleged in this complaint have been in or affecting commerce, as “commerce” is defined in Section 4 of the FTC Act. RESPONDENT’S BUSINESS PRACTICES 3. Google is a technology company best known for its web-based search engine, which provides free search results to consumers. Google also provides various free web products to consumers, including its widely used web-based email service, Gmail, which has been available since April 2004. Among other things, Gmail allows consumers to send and receive emails, chat with other users through Google’s instant messaging service, Google Chat, and store email messages, contact lists, and other information on Google’s servers. 4. Google’s free web products for consumers also include: Google Reader, which allows users to subscribe to, read, and share content online; Picasa, which allows users to edit, post, and share digital photos; and Blogger, Google’s weblog publishing tool that allows users to share text, photos, and video.