ENGLISH THROUGH READING MODERN LITERATURE Part I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p. -

Hidden Lives: Asceticism and Interiority in the Late Reformation, 1650-1745

Hidden Lives: Asceticism and Interiority in the Late Reformation, 1650-1745 By Timothy Cotton Wright A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Jonathan Sheehan, chair Professor Ethan Shagan Professor Niklaus Largier Summer 2018 Abstract Hidden Lives: Asceticism and Interiority in the Late Reformation, 1650-1745 By Timothy Cotton Wright Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Jonathan Sheehan, Chair This dissertation explores a unique religious awakening among early modern Protestants whose primary feature was a revival of ascetic, monastic practices a century after the early Reformers condemned such practices. By the early seventeenth-century, a widespread dissatisfaction can be discerned among many awakened Protestants at the suppression of the monastic life and a new interest in reintroducing ascetic practices like celibacy, poverty, and solitary withdrawal to Protestant devotion. The introduction and chapter one explain how the absence of monasticism as an institutionally sanctioned means to express intensified holiness posed a problem to many Protestants. Large numbers of dissenters fled the mainstream Protestant religions—along with what they viewed as an increasingly materialistic, urbanized world—to seek new ways to experience God through lives of seclusion and ascetic self-deprival. In the following chapters, I show how this ascetic impulse drove the formation of new religious communities, transatlantic migration, and gave birth to new attitudes and practices toward sexuality and gender among Protestants. The study consists of four case studies, each examining a different non-conformist community that experimented with ascetic ritual and monasticism. -

Jahresbericht 2019 Jahresbericht 2019 Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden Staatliche Kunstsammlungen

www.skd.museum Jahresbericht Jahresbericht 2019 Jahresbericht 2019 Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Jahresbericht 2019 Inhalt Vorwort »library of exile«: Edmund de Waal im Gespräch 4 Prof. Dr. Marion Ackermann 36 über seine Beziehung zu Dresden Perspektivwechsel: Ausstellungen im Leipziger 38 GRASSI hinterfragten Blicke auf die Anderen Im Fokus Rembrandts Strich: Zum 350. Todestag präsentierte das Kupferstich-Kabinett Residenzschloss: 40 Grafiken des Meisters 8 Wiedereröffnung Paraderäume Alle saßen ihm Modell: Residenzschloss: Die Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister würdigt 12 Wiedereröffnung Kleiner Ballsaal 42 Anton Graff als Porträtisten seiner Zeit Outreach: Surrealistische Wunderkammer: 13 Engagement im Freistaat Sachen 44 Der Lipsiusbau präsentierte das Künstlerpaar Gemäldgegalerie Alte Meister: Jan und Eva Švankmajer 16 Restaurierung von Vermeers »Briefleserin« Internationale Präsenz der Kunstsammlungen in Historisches Grünes Gewölbe: 46 New York, Los Angeles, Coventry und Amsterdam 18 Einbruch und Diebstahl Sonderausstellungen Münzkabinett: Jubiläumsausstellung 48 20 zum 500. Geburtstag Institution im Wandel Ausstellungen Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister: 56 Auf dem Weg zum Bauhaus: Das Kupferstich- Auf dem Weg zur Wiedereröffnung Kabinett und das Albertinum verdeutlichten Vom 3-D-Modell zum Tablet: 24 Dresdens Rolle zu Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts 58 Digitalisierung im Museumsalltag Zäsur 1989: Das Albertinum erinnerte an die Arbeiten mit der Schatztruhe: 27 Maueröffnung und die Folgen 60 Léontine Meijer-van Mensch -

Inventaire Du Fonds Schooneveld

CHvS library - Q … p. 1 Q The Qualifying Adjective in Spanish (by Ernesto Zierer), The Hague 1974. no.192, Janua Linguarum, series practica *Quellen zum Leben Karis des grossen (heraus. G. Frenke), Berlin 1931. fasc.2, Eclogae graecolatine Quelques remarques sur la flexion nominale romane (red. Maria Manoliu-Manea), Bucarest 1970. no.III, Collection de la société roumaine de linguistique romane *Que sais-je ?, Paris no.82, A.-M. Schmidt, La littérature symboliste 1955 no.123, Ph. van Tieghem, Le romantisme français 1955 no.156, V.-L. Saulnier, La littérature française du siècle romantique 1955 (two copies) no.570, Jean Perrot, La linguistique 1965 no.637, Bertil Malmberg, La phonétique 1954 no.788, Pierre Guiraud, La grammaire 1964 *Qu’est-ce que le structuralisme? (by Oswald Ducrot, Tzvetan Todorov, Dan Sperber, Moustafa Safouan, François Wahl), Paris 1968 Questions and Answers in English (by Emily Norwood Pope), The Hague 1976. no.226, Janua Linguarum, series practica *Quine, Willard Van Orman, From a Logical Point of View , New York - Evanston 1963. no.9, Logico-philosophical essays *Quine, Willard Van Orman, Methods of Logic , New York 1950 *Quine, Willard Van Orman, Set Theory and its Logic , Cambridge, Mass. 1963 *Quine, Willard Van Orman, Word and Object , New York - London 1960. in Studies in communication Quinting, Gerd, Hesitation Phenomena in Adult Aphasic and Normal Speech , The Hague 1971. no.126, Janua Linguarum, series minor *Quirin, Heniz, Einführung in das Studium der mittelalterlichen Geschichte , Braunschweig - Berlin - Hamburg 1950 *Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech and Jan Svartvik, A Grammar of Contemporary English , New York - London 1972 R *Rabinowitch, Alexander, Prelude to Revolution: the Petrograd Bolsheviks and the July 1917 uprising , Bloomington - London 1968. -

Modern Marionettes: the Triadic Ballet and Utopian Androgyny

Modern Marionettes: The Triadic Ballet and Utopian Androgyny by Laura Arike ©2020 Laura Arike A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts (History of Art and Design) School of Liberal Arts and Sciences Pratt Institute May 2020 Table of Contents List of Illustrations………………………………………….……………………...……………..ii Introduction……………………………………………..………………………………………....1 Chapter 1 History of the Androgyne in Germany…………………………................................................………..……...……………......3 Chapter 2 ‘New Woman’ and ‘New Man’ in Weimar Germany…………………………..……...………….………..……...…………..………..……....9 Chapter 3 Metaphysical Theatre: Oskar Schlemmer’s Utopian Typology…………………………..……...………….………..……...…………..………..…….15 Conclusion………………………………………………………………...………..………...… 22 Illustrations…………………...………………………………………...…………..………...….24 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………….……...…..33 i List of Illustrations Figure 1. Oskar Schlemmer, Composition on Pink Ground (2nd Version), 1930, 51 1/8x38 in., University of California, San Diego. Figure 2. Oskar Schlemmer, Figural Plan K 1 (Figurenplan K 1) , 1921, 16 3/8 x 8 1/4 in., Dallas Museum of Art. Figure 3. Oskar Schlemmer, Triadic Ballet/Set Design , 1922, University of California, San Diego. Figure 4. Otto Dix, Portrait of the Journalist Sylvia von Harden , 1926, oil on wood, 4′0″ x 2′ 11″, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. Figure 5. Anton Raderscjeidt, Young Man with Yellow Gloves , 1921, oil on wood, 10.6 x 7.3 in., private collection. Figure 6. Oskar Schlemmer, drawing from “Man and Art Figure,” 1921, The Theatre of the Bauhaus . Figure 7. Oskar Schlemmer, drawing from “Man and Art Figure,” 1921, The Theatre of the Bauhaus . Figure 8. Oskar Schlemmer, drawing from “Man and Art Figure,” 1921, The Theatre of the Bauhaus . Figure 9. Oskar Schlemmer, drawing from “Man and Art Figure,” 1921, The Theatre of the Bauhaus . -

PHILLIP J. PIRAGES Catalogue 66 BINDINGS Catalogue 66 Catalogue

Phillip J. Pirages PHILLIP J. PIRAGES Catalogue 66 BINDINGS Catalogue 66 Items Pictured on the Front Cover 172 176 58 114 92 3 52 167 125 115 192 28 71 161 1 196 204 116 Items Pictured on the Back Cover 152 109 193 9 199 48 83 18 117 25 149 59 83 77 90 60 175 12 149 50 41 91 55 171 143 66 50 126 65 80 98 115 To identify items on the front and back covers, lift this flap up and to the right, then close the cover. Catalogue 66: Interesting Books in Historically Significant and Decorative Bindings, from the 15th Century to the Present Please send orders and inquiries to the above physical or electronic addresses, and do not hesitate to telephone at any time. We would be happy to have you visit us, but please make an appointment so that we are sure to be here. In addition, our website is always open. Prices are in American dollars. Shipping costs are extra. We try to build trust by offering fine quality items and by striving for precision of description because we want you to feel that you can buy from us with confidence. As part of this effort, we unconditionally guarantee your satisfaction. If you buy an item from us and are not satisfied with it, you may return it within 30 days of receipt for a full refund, so long as the item has not been damaged. Most of the text of this catalogue was written by Cokie Anderson, with additional help from Stephen J. -

Bitstream 42365.Pdf

THE TUNES OF DIPLOMATIC NOTES Music and Diplomacy in Southeast Europe (18th–20th century) *This edited collection is a result of the scientific projectIdentities of Serbian Music Within the Local and Global Framework: Traditions, Changes, Challenges (No. 177004, 2011–2019), funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia, and implemented by the Institute of Musicology SASA (Belgrade, Serbia). It is also a result of work on the bilateral project carried out by the Center for International Relations (Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Ljubljana) and the Institute of Musicology SASA (Belgrade, Serbia) entitled Music as a Means of Cultural Diplomacy of Small Transition Countries: The Cases of Slovenia and Serbia(with financial support of ARRS). The process of its publishing was financially supported by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia. THE TUNES OF DIPLOMATIC NOTES MUSIC AND DIPLOMACY IN SOUTHEAST EUROPE (18th–20th CENTURY) Edited by Ivana Vesić, Vesna Peno, Boštjan Udovič Belgrade and Ljubljana, 2020 CONTENTS Acknowledgements ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 7 1. Introduction ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������9 Ivana Vesić, Vesna Peno, Boštjan Udovič Part I. Diplomacy Behind the Scenes: Musicians’ Contact With the Diplomatic Sphere 2. The European Character of Dubrovnik and the Dalmatian Littoral at the End of the Enlightenment Period: Music and Diplomatic Ties of Luka and Miho Sorkočević, Julije Bajamonti and Ruđer Bošković ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������17 Ivana Tomić Ferić 3. The Birth of the Serbian National Music Project Under the Influence of Diplomacy ���������37 Vesna Peno, Goran Vasin 4. Petar Bingulac, Musicologist and Music Critic in the Diplomatic Service ������������������53 Ratomir Milikić Part II. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

Annual Report

July 1, 2007–June 30, 2008 AnnuAl RepoRt 1 Contents 3 Board of Trustees 4 Trustee Committees 7 Message from the Director 12 Message from the Co-Chairmen 14 Message from the President 16 Renovation and Expansion 24 Collections 55 Exhibitions 60 Performing Arts, Music, and Film 65 Community Support 116 Education and Public Programs Cover: Banners get right to the point. After more than 131 Staff List three years, visitors can 137 Financial Report once again enjoy part of the permanent collection. 138 Treasurer Right: Tibetan Man’s Robe, Chuba; 17th century; China, Qing dynasty; satin weave T with supplementary weft Prober patterning; silk, gilt-metal . J en thread, and peacock- V E feathered thread; 184 x : ST O T 129 cm; Norman O. Stone O PH and Ella A. Stone Memorial er V O Fund 2007.216. C 2 Board of Trustees Officers Standing Trustees Stephen E. Myers Trustees Emeriti Honorary Trustees Alfred M. Rankin Jr. Virginia N. Barbato Frederick R. Nance Peter B. Lewis Joyce G. Ames President James T. Bartlett Anne Hollis Perkins William R. Robertson Mrs. Noah L. Butkin+ James T. Bartlett James S. Berkman Alfred M. Rankin Jr. Elliott L. Schlang Mrs. Ellen Wade Chinn+ Chair Charles P. Bolton James A. Ratner Michael Sherwin Helen Collis Michael J. Horvitz Chair Sarah S. Cutler Donna S. Reid Eugene Stevens Mrs. John Flower Richard Fearon Dr. Eugene T. W. Sanders Mrs. Robert I. Gale Jr. Sarah S. Cutler Life Trustees Vice President Helen Forbes-Fields David M. Schneider Robert D. Gries Elisabeth H. Alexander Ellen Stirn Mavec Robert W. -

19 Oap Handbook Body

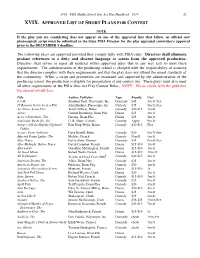

2018 - PSIA Middle School One-Act Play Handbook - 2019 32 XVIX. APPROVED LIST OF SHORT PLAYS FOR CONTEST NOTE: If the play you are considering does not appear on one of the approved lists that follow, an official (not photocopied) script must be submitted to the State PSIA Director for the play appraisal committee’s approval prior to the DECEMBER 1 deadline. The following plays are approved provided they comply fully with PSIA rules. Directors shall eliminate profane references to a deity and obscene language or scenes from the approved production. Directors shall revise or reject all material within approved plays that in any way fails to meet these requirements. The administration of the producing school is charged with the responsibility of assuring that the director complies with these requirements and that the play does not offend the moral standards of the community. When a script and production are examined and approved by the administration of the producing school, the production is eligible for presentation at any contest site. These plays must also meet all other requirements of the PSIA One-Act Play Contest Rules. NOTE: Please check with the publisher for current royalty fees. Title Author, Publisher Type Royalty Cast 4 A.M. Jonathan Dorf, Playscripts, Inc. Dramedy $45 3m-3f-flex 15 Reasons Not to be in a Play Alan Haehnel, Playscripts, Inc. Comedy $45 8m-7f-flex Act Three, Scene Five Terry Ortwein, Baker Comedy $20-$15 1m-4f Actors Conrad Bromberg, Dram Play Drama $25 2m-1f Actor’s Nightmare, The Durang, Dram Play Drama $25 2m-3f Admirable Bashville, The G. -

LE SYMBOLISME EN EUROPE (1880-1914) Michèle-Ann PILLET Au Royaume Du Temps, Le 19E Siècle Eut Le Privilège D'élargir

LE SYMBOLISME EN EUROPE (1880-1914) Michèle-Ann PILLET Au royaume du temps, le 19e siècle eut le privilège d’élargir l’horizon de l’avenir au gré des innovations techniques et scientifiques mais également au fil des redécouvertes du passé. Revêtue de lointains, la préhistoire se présentait escortée de silex et de peintures pariétales. La Mésopotamie, après un long sommeil de sable, révélait en cunéiformes combien la pensée grecque et la pensée hébraïque lui étaient redevables. D’élégants hiéroglyphes apportaient en offrandes les secrets de l’Egypte. Le jour, avec courtoisie, relevait de sa lumière les cités de la Grèce et de la Rome antiques. Le Moyen-âge, voilé d’imaginaire, reprenait sa place en majesté après des siècles de mépris. Et les musées s’inventaient… Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis Cependant, le témoignage diapré de la valeur du passé comme garant d’avenir, donné par un groupe de poètes et d’artistes, devait offrir à ce siècle un crépuscule d’or fané effleuré par le pourpre d’un souffle créateur. En affirmant leur appartenance au Symbolisme, ils se référaient ainsi à une ère originelle. Baudelaire et Wagner furent les figures tutélaires de cet élan. Aussi ancien que l’apparition de l’homme sur la terre, le symbolisme est une disposition universelle de l’esprit qui a présidé à l’invention du langage lorsque l’homme a souhaité représenter par un son, une image ou un objet les éléments de la réalité qui l’entouraient. Ceci lui a permis de faire exister ces éléments hors du champ visuel et d’établir des liens 1 avec l’univers. -

Director's Copy

The Old Testament Fast Forward Production Notes: The portions of the script that follow provide a companion guide to The Old Testament Fast Forward, giving additional production details and suggestions for staging. In the original production, the performers “acted out” the lines of verse narration throughout the musical with choreographed movement. That movement is described below. Another option for staging the play is to use projection screens with a program like Power Point, and illustrate the verse narrations and other sections of the musical with fast changing slides. Notes for Page 7: (At the end of “God’s Word,” the accompanist can replay the last few measures of the song as the cast move to new positions. On stage left, ADAM stands in front of a box with his back to the audience. EVE stands behind the box, also facing upstage. Two other actors stand with their backs to the audience on either side of the box. On stage right, a group of seven actors stand, backs to audience. The rest of the CAST move upstage and sit, taking themselves out of the focus. Following the music, we hear four percussion clicks and then a snare brush rhythm begins. Throughout the show, the NARRATORS recite their verse lines to this rhythm freely, with a bit of syncopation.) VERSE NARRATION 1: NARRATOR 1: In the beginning, God creates, Six days working, (Six of the actors on stage right flip to face the audience and pose as though digging.) seventh waits. (The seventh actor on stage right flips to the audience and poses, looking at his watch.) NARRATOR 2: In God’s image, man is made, (ADAM turns quickly to face the audience.) Set to rest in Eden’s shade.