A Performer's Guide to Iosif Andriasov's "Concertino for Trumpet" Andrew K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JAVS 32.3.Pdf

Viola V33 N1.indd 302 5/8/17 10:10 PM Journal of the American Viola Society A publication of the American Viola Society Spring 2017: Volume 33, Number 1 p. 3 From the Editor p. 5 From the President News & Notes p. 7 Announcements p. 8 The Lionel ertis-JohnT White Collection p. 11 In Memoriam: Bernie Zaslav Feature Articles p. 13 The Genesis of BenjaminYusupov’s Viola Tango Rock Concerto: Dalton Competition Winner Andrea Carolina del Pilar Sánchez Ruiz presents her research on one of the first viola concertos to be premiered in the twenty-first century. p. 27 Grigori Frid and the Viola: In Conversation with the Composer: Elena Artamonova introduces a composer whose work is little known amongst violists, providing fascinating background and connections to twentieth-century Soviet Russian music. Departments p. 37 Outreach: Carol Rodland writes about her very practical and creative “If Music Be the Food…” program, for which volunteers and musicians donate their time to help raise monetary and non-perishable food donations for Foodlink, the Feeding America Hub of Western New York. p. 39 Health and Wellness: Our new Health and Wellness Editor, Jessica Ray King, introduces her new column with some of her more recent research. On the Cover: Joyce Lin Viola 24 x 36 inches Watercolor, graphite Joyce Lin is an artist and designer studying Furniture Design at the Rhode Island School of Design and Geology at Brown University as part of the Brown/RISD Dual Degree program. Her drawing is a full-scale technical rendering of her friend’s beloved viola, first drawn on a computer-aided design (CAD) program and then traced onto paper, as an exercise in measurement and detail. -

State Composers and the Red Courtiers: Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930S

JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s Esitetään Jyväskylän yliopiston humanistisen tiedekunnan suostumuksella julkisesti tarkastettavaksi yliopiston Villa Ranan Blomstedtin salissa marraskuun 24. päivänä 2007 kello 12. Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by permission of the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Jyväskylä, in the Building Villa Rana, Blomstedt Hall, on November 24, 2007 at 12 o'clock noon. UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2007 State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2007 Editors Seppo Zetterberg Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Irene Ylönen, Marja-Leena Tynkkynen Publishing Unit, University Library of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities Editorial Board Editor in Chief Heikki Hanka, Department of Art and Culture Studies, University of Jyväskylä Petri Karonen, Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Matti Rahkonen, Department of Languages, University of Jyväskylä Petri Toiviainen, Department of Music, University of Jyväskylä Minna-Riitta Luukka, Centre for Applied Language Studies, University of Jyväskylä Raimo Salokangas, Department of Communication, University of Jyväskylä URN:ISBN:9789513930158 ISBN 978-951-39-3015-8 (PDF) ISBN 978-951-39-2990-9 (nid.) ISSN 1459-4331 Copyright ©2007 , by University of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä University Printing House, Jyväskylä 2007 ABSTRACT Mikkonen, Simo State composers and the red courtiers. -

ANATOLY ALEXANDROV Piano Music, Volume One

ANATOLY ALEXANDROV Piano Music, Volume One 1 Ballade, Op. 49 (1939, rev. 1958)* 9:40 Romantic Episodes, Op. 88 (1962) 19:39 15 No. 1 Moderato 1:38 Four Narratives, Op. 48 (1939)* 11:25 16 No. 2 Allegro molto 1:15 2 No. 1 Andante 3:12 17 No. 3 Sostenuto, severo 3:35 3 No. 2 ‘What the sea spoke about 18 No. 4 Andantino, molto grazioso during the storm’: e rubato 0:57 Allegro impetuoso 2:00 19 No. 5 Allegro 0:49 4 No. 3 ‘What the sea spoke of on the 20 No. 6 Adagio, cantabile 3:19 morning after the storm’: 21 No. 7 Andante 1:48 Andantino, un poco con moto 3:48 22 No. 8 Allegro giocoso 2:47 5 No. 4 ‘In memory of A. M. Dianov’: 23 No. 9 Sostenuto, lugubre 1:35 Andante, molto cantabile 2:25 24 No. 10 Tempestoso e maestoso 1:56 Piano Sonata No. 8 in B flat, Op. 50 TT 71:01 (1939–44)** 15:00 6 I Allegretto giocoso 4:21 Kyung-Ah Noh, piano 7 II Andante cantabile e pensieroso 3:24 8 III Energico. Con moto assai 7:15 *FIRST RECORDING; **FIRST RECORDING ON CD Echoes of the Theatre, Op. 60 (mid-1940s)* 14:59 9 No. 1 Aria: Adagio molto cantabile 2:27 10 No. 2 Galliarde and Pavana: Vivo 3:20 11 No. 3 Chorale and Polka: Andante 2:57 12 No. 4 Waltz: Tempo di valse tranquillo 1:32 13 No. 5 Dances in the Square and Siciliana: Quasi improvisata – Allegretto 2:24 14 No. -

Toccata Classics TOCC 0127 Notes

SERGEI VASILENKO AND THE VIOLA by Elena Artamonova The viola is occasionally referred to as ‘the Cinderella of instruments’ – and, indeed, it used to take a fairy godmother of a player to allow this particular Cinderella to go to the ball; the example usually cited in the liberation of the viola in a solo role is the British violist Lionel Tertis. Another musician to pay the instrument a similar honour – as a composer rather than a player – was the Russian Sergei Vasilenko (1872–1956), all of whose known compositions for viola, published and unpublished, are to be heard on this CD, the fruit of my investigations in libraries and archives in Moscow and London. None is well known; some are not even included in any of the published catalogues of Vasilenko’s music. Only the Sonata was recorded previously, first in the 1960s by Georgy Bezrukov, viola, and Anatoly Spivak, piano,1 and again in 2007 by Igor Fedotov, viola, and Leonid Vechkhayzer, piano;2 the other compositions receive their first recordings here. Sergei Nikiforovich Vasilenko had a long and distinguished career as composer, conductor and pedagogue in the first half of the twentieth century. He was born in Moscow on 30 March 1872 into an aristocratic family, whose inner circle of friends consisted of the leading writers and artists of the time, but his interest in music was rather capricious in his early childhood: he started to play piano from the age of six only to give it up a year later, although he eventually resumed his lessons. In his mid-teens, after two years of tuition on the clarinet, he likewise gave it up in favour of the oboe. -

TOCC0330DIGIBKLT.Pdf

GRIGORI FRID IN MEMORIAM by Elena Artamonova Grigori Samuilovich Frid (1915–2012) was a versatile Soviet-Russian composer, best known outside Russia for his ‘mono-operas’ (that is, with a single vocal soloist) The Diary of Anna Frank (1969) and The Letters of van Gogh (1975), which deservedly received a degree of international recognition. But they form only a small part of Frid’s extensive legacy, which includes three symphonies (1939, 1955, 1964), overtures and suites for symphony orchestra, four instrumental concertos (for violin, trombone and two for viola), a vocal-instrumental cycle after Federico Garcia Lorca, Poetry (1973), numerous chamber works for piano, violin, viola, cello, flute, oboe, clarinet and trumpet, five string quartets (1936, 1947, 1949, 1957, 1977), two piano quintets (1981, 1985), music for folk instruments, vocal and choral music, incidental music for various theatre and radio productions, film scores and music for children. The majority of these works have been performed, but hardly any have been recorded. From 1947 to 1963, Frid taught composition at the Moscow Conservatoire Music College. Among his students were the future composers Nikolai Korndorf, Maxim Dunaevsky, Alexandre Rabinovitch and Alexander Vustin.1 Frid was also a gifted writer, publishing six books (two books of essays on music, a novel and three books of memoirs), and a talented artist. From 1967 he regularly exhibited his paintings, which now hang in private collections in the USA, Finland, Germany, Israel and Russia. But even then the long and varied list of Frid’s accomplishments is not complete. For at least three generations of Muscovites, he is particularly well known as a tireless educator, as the presenter and one of the founding members of the Moskovskii Molodezhnyi Muzykal’nyi Klub (‘Moscow Musical Youth Club’) at the Composers’ Union (first of the USSR, and then of the Russian Federation) that Frid organised and led (with no financial reward) for almost half a century, from the day of its foundation on 21 October 1965 until his death. -

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET CONCERTOS a Discography Of

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET CONCERTOS A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Edited by Stephen Ellis Composers H-P GAGIK HOVUNTS (see OVUNTS) AIRAT ICHMOURATOV (b. 1973) Born in Kazan, Tatarstan, Russia. He studied clarinet at the Kazan Music School, Kazan Music College and the Kazan Conservatory. He was appointed as associate clarinetist of the Tatarstan's Opera and Ballet Theatre, and of the Kazan State Symphony Orchestra. He toured extensively in Europe, then went to Canada where he settled permanently in 1998. He completed his musical education at the University of Montreal where he studied with Andre Moisan. He works as a conductor and Klezmer clarinetist and has composed a sizeable body of music. He has written a number of concertante works including Concerto for Viola and Orchestra No1, Op.7 (2004), Concerto for Viola and String Orchestra with Harpsicord No. 2, Op.41 “in Baroque style” (2015), Concerto for Oboe and Strings with Percussions, Op.6 (2004), Concerto for Cello and String Orchestra with Percussion, Op.18 (2009) and Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, Op 40 (2014). Concerto Grosso No. 1, Op.28 for Clarinet, Violin, Viola, Cello, Piano and String Orchestra with Percussion (2011) Evgeny Bushko/Belarusian State Chamber Orchestra ( + 3 Romances for Viola and Strings with Harp and Letter from an Unknown Woman) CHANDOS CHAN20141 (2019) 3 Romances for Viola and Strings with Harp (2009) Elvira Misbakhova (viola)/Evgeny Bushko/Belarusian State Chamber Orchestra ( + Concerto Grosso No. 1 and Letter from an Unknown Woman) CHANDOS CHAN20141 (2019) ARSHAK IKILIKIAN (b. 1948, ARMENIA) Born in Gyumri Armenia. -

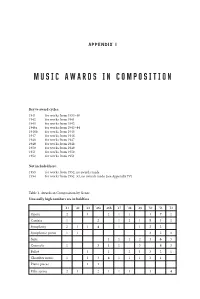

4932 Appendices Only for Online.Indd

APPENDIX I MUSIC AWARDS IN COMPOSITION Key to award cycles: 1941 for works from 1934–40 1942 for works from 1941 1943 for works from 1942 1946a for works from 1943–44 1946b for works from 1945 1947 for works from 1946 1948 for works from 1947 1949 for works from 1948 1950 for works from 1949 1951 for works from 1950 1952 for works from 1951 Not included here: 1953 for works from 1952, no awards made 1954 for works from 1952–53, no awards made (see Appendix IV) Table 1. Awards in Composition by Genre Unusually high numbers are in boldface ’41 ’42 ’43 ’46a ’46b ’47 ’48 ’49 ’50 ’51 ’52 Opera2121117 2 Cantata 1 2 1 2 1 5 32 Symphony 2 1 1 4 1122 Symphonic poem 1 1 3 2 3 Suite 111216 3 Concerto 1 3 1 1 3 4 3 Ballet 1 1 21321 Chamber music 1 1 3 4 11131 Piano pieces 1 1 Film scores 21 2111 1 4 APPENDIX I MUSIC AWARDS IN COMPOSITION Songs 2121121 6 3 Art songs 1 2 Marches 1 Incidental music 1 Folk instruments 111 Table 2. Composers in Alphabetical Order Surnames are given in the most common transliteration (e.g. as in Wikipedia); first names are mostly given in the familiar anglicized form. Name Alternative Spellings/ Dates Class and Year Notes Transliterations of Awards 1. Afanasyev, Leonid 1921–1995 III, 1952 2. Aleksandrov, 1883–1946 I, 1942 see performers list Alexander for a further award (Appendix II) 3. Aleksandrov, 1888–1982 II, 1951 Anatoly 4. -

Mandelstam, Blok, and the Boundaries of Mythopoetic Symbolism Myopoetic Symbolism Mandelstam, Blok, and the Boundaries of Mythopoetic Symbolism

MANDELSTAM, BLOK, AND THE BOUNDARIES OF MYTHOPOETIC SYMBOLISM MYOPOETIC SYMBOLISM MANDELSTAM, BLOK, AND THE BOUNDARIES OF MYTHOPOETIC SYMBOLISM STUART GOLDBERG THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS | COLUMBUS Copyright © 2011 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Goldberg, Stuart, 1971– Mandelstam, Blok, and the boundaries of mythopoetic symbolism / Stuart Goldberg. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8142-1159-5 (cloth : alk. paper)—ISBN 978-0-8142-9260-0 (cd) 1. Russian poetry—20th century—History and criticism. 2. Symbolism in literature. 3. Mandel’shtam, Osip, 1891–1938—Criticism and interpretation. 4. Blok, Aleksandr Alek- sandrovich, 1880–1921—Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. PG3065.S8G65 2011 891.71'3—dc22 2011013260 Cover design by James A. Baumann Text design by Juliet Williams Type set in Adobe Minion Pro Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Диночке с любовью CONTENTS Acknowledgments ix Note on Transliteration xiii PART I Chapter 1 Introduction 3 Immediacy and Distance 3 “The living and dangerous Blok . .” 6 Symbolism and Acmeism: An Overview 8 The Curtain and the Onionskin 15 Chapter 2 Prescient Evasions of Bloom 21 PART II Chapter 3 Departure 35 Chapter 4 The Pendulum at the Heart of Stone 49 Chapter 5 Struggling with the Faith -

Tocc0324dbook.Pdf

MATVEY NIKOLAEVSKY: A LIGHT-MUSIC MASTER REDISCOVERED by Anthony Phillips History – not least the tangled cultural history of Soviet Russia – has not been kind to the gifted Matvey Nikolaevsky. Yet on 27 May 1938, at the peak of his popularity in the 1920s and ’30s, an astonishing array of the cream of Soviet musical life filled the Great Hall of the Moscow Conservatoire to celebrate the 35th anniversary of Nikolaevsky’s artistic career – although his handwritten autobiographical résumé reveals that his working life had begun much earlier, at the age of twelve. His career embraced distinction as pianist, as composer of a string of universally known and loved ballads, popular songs, dance numbers, orchestral marches and genre pieces, and as a much-respected piano teacher with several books of keyboard technique instruction to his credit. One at least such tutor, entitled Conservatoire [i.e., ‘correct’] Positioning of the Hand on the Piano, first appearing in 1917, has been republished countless times, is in print and is widely used to this day. Among the famous names from the world of music, opera and ballet taking part in the 1938 gala concert were the composers Reinhold Glière and Sergei Vasilenko; the conductors Nikolai Golovanov (music director of the Bolshoi Theatre), Yuri Feier, Alexander Melik-Pashayev and Samuil Samosud; the pianist Alexander Goldenweiser, then Rector of the Moscow Conservatoire; the prodigy violinist Busya Goldstein; a clutch of the Soviet Union’s most celebrated singers: the sopranos Antonina Nezhdanova and Maria -

Russian Connection Text Booklet

Three generations of composers, one Russian tradition The most substantial work on this CD, Rimsky-Korsakov’s Quintet in B flat, is entirely in the tradition of the Russia of the Tsars and the divertimento by Paul Juon was also written before the Revolution. The works by Ippolitov-Ivanov and Vasilenko were composed during the first decades of the Soviet Union. The establishment of the Soviet regime was a cultural turning point as well as a political one, so that the four works on this CD might seem to represent two entirely different worlds. But even though Ippolitov-Ivanov and Vasilenko were certainly influenced by cultural and political changes, the level of continuity is greater than one would expect. The main reason for this is to be found in the conservative idiom of these two composers. In addition, we are dealing with a strong tradition, one which was not easy to break with and which later turned out to be politically useful. On the present CD that tradition is represented by three generations of a “family” of composers. Rimsky- Korsakov taught Ippolitov-Ivanov, who in turn was the teacher of Vasilenko. Despite stylistic differences, Paul Juon can be considered a distant musical cousin of Vasilenko. Not only were they precisely the same age –both being born in March 1872– but they were contemporaries at the Moscow Conservatory. The compositions of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844-1908) can be divided into four different periods. Prior to 1873 he concentrated mainly on symphonies, but in about 1878 he commenced a series of impressive operas. -

Tchaikovsky · Prokofiev Khachaturian

Russian Ballets Suites from: Swan Lake · Sleeping Beauty The Nutcracker · Cinderella The Stone Flower · Romeo and Juliet Gayaneh · Spartacus Tchaikovsky · Prokofiev Khachaturian Royal Philharmonic Orchestra Novosibirsk Symphony Orchestra Bolshoi Theatre Orchestra RUSSIAN BALLETS 10. The Wedding. No.24 Pas de caractère Tchaikovsky, Prokofiev, Khatchaturian (Puss-in-Boots and the White Cat) (Allegro moderato) 2’30 11. The Wedding: No.28 Pas de deux (Auroroa and Florimund) Adagio (Andante non troppo) 4’43 PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY 1840-1893 12. The Wedding: No.28 Pas de deux (Aurora and Florimund) Swan Lake Op.20 Coda (Allegro Vivace) 1’19 Act I 13. The Wedding: No.30 Finale (Alegro brillante: Tempo di mazurka) 4’02 1. No.2 Waltz (Tempo di valse) 7’17 Act II The Nutcracker Op.71 2. No.10 Scene – Swan Theme (Moderato) 6’31 14. Miniature Overture 3’21 3. No.13 Dance of the Little Swans (Allegro moderato) 1’27 Act I 4. No.13 Pas d’action – Second Dance of the Queen 15. No.2 March 2’19 Andante non troppo – Allegro 8’04 Act II Act III 16. No.12 Divertissement. Coffee: Arabian Dance 3’23 5. No.20 Hungarian Dance: Csárdás (Moderato assai – 17. No.12 Divertissement. Tea: Chinese Dance 1’06 Allegro moderato – Vivace) 3’46 18. No.12 Divertissement. Trepak: Russian Dance 1’09 6. No.21 Spanish Dance (Allegro non troppo: Tempo di Bolero) 2’28 19. No.12 Divertissement. Dance of the Reed Pipes 2’21 20. No.14 Pas de deux. Variation 2: Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy 4’29 Sleeping Beauty Op.66 21. -

Forgotten Russian Piano Music: the Sonatas of Anatoly Aleksandrov Irina Pevzner University of South Carolina

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 1-1-2013 Forgotten Russian Piano Music: the Sonatas of Anatoly Aleksandrov Irina Pevzner University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Pevzner, I.(2013). Forgotten Russian Piano Music: the Sonatas of Anatoly Aleksandrov. (Master's thesis). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/2559 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FORGOTTEN RUSSIAN PIANO MUSIC: THE SONATAS OF ANATOLY ALEKSANDROV by Irina Pevzner Bachelor of Music Mansfield University of Pennsylvania, 2000 Master of Music Carnegie Mellon University, 2003 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Performance School of Music University of South Carolina 2013 Accepted by: Marina Lomazov, Major Professor Chairman, Examining Committee Charles Fugo, Committee Member Joseph Rackers, Committee Member Ellen Exner, Committee Member Lacy Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright by Irina Pevzner, 2013 All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge several individuals, who played an important role in preparation of the current document. Above all, I would like to distinguish Dr. Marina Lomazov, my piano professor and the director of the dissertation committee, for inspiring me to achieve a higher level of musicianship and guiding me with unreserved care and perseverance to become a more confident and competent performer.