Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston Early Music Festival Announces 2013 Festival

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: April 1, 2012 CONTACT: Kathleen Fay, Executive Director | Boston Early Music Festival 161 First Street, Suite 202 | Cambridge, MA 02142 617-661-1812 | [email protected] | www.bemf.org BOSTON EARLY MUSIC FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES 2013 FESTIVAL OPERATIC CENTERPIECE , HANDEL ’S ALMIRA Cambridge, MA – April 1, 2012 – The Boston Early Music Festival has announced plans for the 2013 Festival fully-staged Operatic Centerpiece Almira, the first opera by the celebrated and beloved Baroque composer, George Frideric Handel (1685–1759), in its first modern-day historically-conceived production. Written when he was only 19, Almira tells a story of intrigue and romance in the court of the Queen of Castile, in a dazzling parade of entertainment and delight which Handel would often borrow from during his later career. One of the world’s leading Handel scholars, Professor Ellen T. Harris of MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), has said that BEMF is the “perfect and only” organization to take on Handel’s earliest operatic masterpiece, as it requires BEMF’s unique collection of artistic talents: the musical leadership, precision, and expertise of BEMF Artistic Directors Paul O’Dette and Stephen Stubbs; the stimulating and informed stage direction and magnificent production designs of BEMF Stage Director in Residence Gilbert Blin; “the world’s finest continuo team, which you have”; the highly skilled BEMF Baroque Dance Ensemble to bring to life Almira ’s substantial dance sequences; the all-star BEMF Orchestra; and a wide range of superb voices. BEMF will offer five fully-staged performances of Handel’s Almira from June 9 to 16, 2013 at the Cutler Majestic Theatre at Emerson College (219 Tremont Street, Boston, MA, USA), followed by three performances at the Mahaiwe Performing Arts Center (14 Castle Street, Great Barrington, MA, USA) on June 21, 22, and 23, 2013 ; all performances will be sung in German with English subtitles. -

The Music the Music-To-Go Trio Wedding Guide Go Trio Wedding

The MusicMusic----ToToToTo----GoGo Trio Wedding Guide Processionals Trumpet Voluntary.................................................................................Clarke Wedding March.....................................................................................Wagner Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring...................................................................... Bach Te Deum Prelude.......................................................................... Charpentier Canon ................................................................................................. Pachelbel Air from Water Music............................................................................. Handel Sleepers Awake.......................................................................................... Bach Sheep May Safely Graze........................................................................... Bach Air on the G String................................................................................... Bach Winter (Largo) from The Four Seasons ..................................................Vivaldi MidMid----CeremonyCeremony Music Meditations, Candle Lightings, Presentations etc. Ave Maria.............................................................................................Schubert Ave Maria...................................................................................Bach-Gounod Arioso......................................................................................................... Bach Meditation from Thaïs ......................................................................Massenet -

What Handel Taught the Viennese About the Trombone

291 What Handel Taught the Viennese about the Trombone David M. Guion Vienna became the musical capital of the world in the late eighteenth century, largely because its composers so successfully adapted and blended the best of the various national styles: German, Italian, French, and, yes, English. Handel’s oratorios were well known to the Viennese and very influential.1 His influence extended even to the way most of the greatest of them wrote trombone parts. It is well known that Viennese composers used the trombone extensively at a time when it was little used elsewhere in the world. While Fux, Caldara, and their contemporaries were using the trombone not only routinely to double the chorus in their liturgical music and sacred dramas, but also frequently as a solo instrument, composers elsewhere used it sparingly if at all. The trombone was virtually unknown in France. It had disappeared from German courts and was no longer automatically used by composers working in German towns. J.S. Bach used the trombone in only fifteen of his more than 200 extant cantatas. Trombonists were on the payroll of San Petronio in Bologna as late as 1729, apparently longer than in most major Italian churches, and in the town band (Concerto Palatino) until 1779. But they were available in England only between about 1738 and 1741. Handel called for them in Saul and Israel in Egypt. It is my contention that the influence of these two oratorios on Gluck and Haydn changed the way Viennese composers wrote trombone parts. Fux, Caldara, and the generations that followed used trombones only in church music and oratorios. -

Handel's Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment By

Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Emeritus John H. Roberts Professor George Haggerty, UC Riverside Professor Kevis Goodman Fall 2013 Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment Copyright 2013 by Jonathan Rhodes Lee ABSTRACT Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Throughout the 1740s and early 1750s, Handel produced a dozen dramatic oratorios. These works and the people involved in their creation were part of a widespread culture of sentiment. This term encompasses the philosophers who praised an innate “moral sense,” the novelists who aimed to train morality by reducing audiences to tears, and the playwrights who sought (as Colley Cibber put it) to promote “the Interest and Honour of Virtue.” The oratorio, with its English libretti, moralizing lessons, and music that exerted profound effects on the sensibility of the British public, was the ideal vehicle for writers of sentimental persuasions. My dissertation explores how the pervasive sentimentalism in England, reaching first maturity right when Handel committed himself to the oratorio, influenced his last masterpieces as much as it did other artistic products of the mid- eighteenth century. When searching for relationships between music and sentimentalism, historians have logically started with literary influences, from direct transferences, such as operatic settings of Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, to indirect ones, such as the model that the Pamela character served for the Ninas, Cecchinas, and other garden girls of late eighteenth-century opera. -

HANDEL: Coronation Anthems Winner of the Gramophone Award for Cor16066 Best Baroque Vocal Album 2009

CORO CORO HANDEL: Coronation Anthems Winner of the Gramophone Award for cor16066 Best Baroque Vocal Album 2009 “Overall, this disc ranks as The Sixteen’s most exciting achievement in its impressive Handel discography.” HANDEL gramophone Choruses HANDEL: Dixit Dominus cor16076 STEFFANI: Stabat Mater The Sixteen adds to its stunning Handel collection with a new recording of Dixit Dominus set alongside a little-known treasure – Agostino Steffani’s Stabat Mater. THE HANDEL COLLECTION cor16080 Eight of The Sixteen’s celebrated Handel recordings in one stylish boxed set. The Sixteen To find out more about CORO and to buy CDs visit HARRY CHRISTOPHERS www.thesixteen.com cor16180 He is quite simply the master of chorus and on this compilation there is much rejoicing. Right from the outset, a chorus of Philistines revel in Awake the trumpet’s lofty sound to celebrate Dagon’s festival in Samson; the Israelites triumph in their victory over Goliath with great pageantry in How excellent Thy name from Saul and we can all feel the exuberance of I will sing unto the Lord from Israel in Egypt. There are, of course, two Handel oratorios where the choruses dominate – Messiah and Israel in Egypt – and we have given you a taster of pure majesty in the Amen chorus from Messiah as well as the Photograph: Marco Borggreve Marco Photograph: dramatic ferocity of He smote all the first-born of Egypt from Israel in Egypt. Handel is all about drama; even though he forsook opera for oratorio, his innate sense of the theatrical did not leave him. Just listen to the poignancy of the opening of Act 2 from Acis and Galatea where the chorus pronounce the gloomy prospect of the lovers and the impending appearance of the monster Polyphemus; and the torment which the Israelites create in O God, behold our sore distress when Jephtha commands them to “invoke the holy name of Israel’s God”– it’s surely one of his greatest fugal choruses. -

CHORAL PROBLEMS in HANDEL's MESSIAH THESIS Presented to The

*141 CHORAL PROBLEMS IN HANDEL'S MESSIAH THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By John J. Williams, B. M. Ed. Denton, Texas May, 1968 PREFACE Music of the Baroque era can be best perceived through a detailed study of the elements with which it is constructed. Through the analysis of melodic characteristics, rhythmic characteristics, harmonic characteristics, textural charac- teristics, and formal characteristics, many choral problems related directly to performance practices in the Baroque era may be solved. It certainly cannot be denied that there is a wealth of information written about Handel's Messiah and that readers glancing at this subject might ask, "What is there new to say about Messiah?" or possibly, "I've conducted Messiah so many times that there is absolutely nothing I don't know about it." Familiarity with the work is not sufficient to produce a performance, for when it is executed in this fashion, it becomes merely a convention rather than a carefully pre- pared piece of music. Although the oratorio has retained its popularity for over a hundred years, it is rarely heard as Handel himself performed it. Several editions of the score exist, with changes made by the composer to suit individual soloists or performance conditions. iii The edition chosen for analysis in this study is the one which Handel directed at the Foundling Hospital in London on May 15, 1754. It is version number four of the vocal score published in 1959 by Novello and Company, Limited, London, as edited by Watkins Shaw, based on sets of parts belonging to the Thomas Coram Foundation (The Foundling Hospital). -

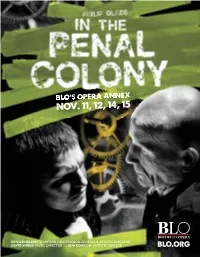

2015 in the Penal Colony Program

ESTHER NELSON, STANFORD CALDERWOOD GENERAL & ARTISTIC DIRECTOR DAVID ANGUS, MUSIC DIRECTOR | JOHN CONKLIN, ARTISTIC ADVISOR Rodolfo (Jesus Garcia) and Mimi (Kelly Kaduce) in Boston Lyric Opera’s 2015 production of La Bohème. This holiday season, share your love of opera with the ones you love. BLO off ers packages and gift certifi cates CHARLES ERICKSON T. to make your holiday shopping simple! T. CHARLES ERICKSON T. WELCOME TO THE SEVENTH IN OUR OPERA ANNEX SERIES, which is increasingly attracting national and international attention. Installing opera in non-conventional spaces has sparked a curiosity in the art. The challenges of these spaces are many and due to opera’s inherent demands: natural acoustics (since we do not amplify), adequate performance and production space, audience comfort and social space, location accessibility, parking, safety, and especially important in New England, adequate heat. Our In the Penal Colony comes amid questions and debate on the performance spaces and theatrical environment in Boston. For us, the questions include … why is Boston the only one of the top ten U.S. cities without a home suitable for opera? What are sustainable models to support new performance venues and/or preserve historic theaters? As you may have heard, BLO decided not to renew its agreement with the JesusJJesus GarciaGGarcia as RRoRodolfodldolffo Shubert Theatre after this Season. The reasons are many and complex, but suffi ce in La Bohème it to say that we made an important business and artistic decision. BLO is dedicated to spending signifi cantly more of our budget on direct artistic and production expenses and providing our patrons with a new level of service and comfort. -

George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) Ellen T

MIT OpenCourseWare http://ocw.mit.edu 21M.013J The Supernatural in Music, Literature and Culture Spring 2009 For information about citing these materials or our Terms of Use, visit: http://ocw.mit.edu/terms. George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) Ellen T. Harris Alcina Opera seria: “serious opera”; the dominant form of opera from the late 17th century through much of the 18th; the texts are mostly based on history or epic and involve ethical or moral dilemmas affecting political and personal relationships that normally find resolution by the end Recitative: “recitation”; the dialogue or “spoken” part of the text, set to music that reflects the speed and intonation of speech; normally it is “simple” recitative, accompanied by a simple bass accompaniment; rarely in moments of great tension there can be additional orchestral accompaniments as in the incantation scene for Alcina (such movements are called “accompanied recitative”) Aria: the arias in opera seria are overwhelmingly in one form where two stanzas of text are set in the pattern ABA; that is, the first section is repeated after the second; during this repetition, the singer is expected to ornament the vocal line to create an intensification of emotion Formal units: individual scenes are normally set up so that a recitative section of dialogue, argument, confrontation, or even monologue leads to an aria in which one of the characters expresses his or her emotional state at that moment in the drama and then exits; this marks the end of the scene; scenes are often demarcated at the beginning -

Iphigénie En Tauride

Christoph Willibald Gluck Iphigénie en Tauride CONDUCTOR Tragedy in four acts Patrick Summers Libretto by Nicolas-François Guillard, after a work by Guymond de la Touche, itself based PRODUCTION Stephen Wadsworth on Euripides SET DESIGNER Saturday, February 26, 2011, 1:00–3:25 pm Thomas Lynch COSTUME DESIGNER Martin Pakledinaz LIGHTING DESIGNER Neil Peter Jampolis CHOREOGRAPHER The production of Iphigénie en Tauride was Daniel Pelzig made possible by a generous gift from Mr. and Mrs. Howard Solomon. Additional funding for this production was provided by Bertita and Guillermo L. Martinez and Barbara Augusta Teichert. The revival of this production was made possible by a GENERAL MANAGER gift from Barbara Augusta Teichert. Peter Gelb MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine Iphigénie en Tauride is a co-production with Seattle Opera. 2010–11 Season The 17th Metropolitan Opera performance of Christoph Willibald Gluck’s Iphigénie en This performance is being broadcast Tauride live over The Toll Brothers– Metropolitan Conductor Opera Patrick Summers International Radio Network, in order of vocal appearance sponsored by Toll Brothers, Iphigénie America’s luxury Susan Graham homebuilder®, with generous First Priestess long-term Lei Xu* support from Second Priestess The Annenberg Cecelia Hall Foundation, the Vincent A. Stabile Thoas Endowment for Gordon Hawkins Broadcast Media, A Scythian Minister and contributions David Won** from listeners worldwide. Oreste Plácido Domingo This performance is Pylade also being broadcast Clytemnestre Paul Groves** Jacqueline Antaramian live on Metropolitan Opera Radio on Diane Agamemnon SIRIUS channel 78 Julie Boulianne Rob Besserer and XM channel 79. Saturday, February 26, 2011, 1:00–3:25 pm This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. -

Handel Rinaldo Tuesday 13 March 2018 6.30Pm, Hall

Handel Rinaldo Tuesday 13 March 2018 6.30pm, Hall The English Concert Harry Bicket conductor/harpsichord Iestyn Davies Rinaldo Jane Archibald Armida Sasha Cooke Goffredo Joélle Harvey Almirena/Siren Luca Pisaroni Argante Jakub Józef Orli ´nski Eustazio Owen Willetts Araldo/Donna/Mago Richard Haughton Richard There will be two intervals of 20 minutes following Act 1 and Act 2 Part of Barbican Presents 2017–18 We appreciate that it’s not always possible to prevent coughing during a performance. But, for the sake of other audience members and the artists, if you feel the need to cough or sneeze, please stifle it with a handkerchief. Programme produced by Harriet Smith; printed by Trade Winds Colour Printers Ltd; advertising by Cabbell (tel 020 3603 7930) Please turn off watch alarms, phones, pagers etc during the performance. Taking photographs, capturing images or using recording devices during a performance is strictly prohibited. If anything limits your enjoyment please let us know The City of London during your visit. Additional feedback can be given Corporation is the founder and online, as well as via feedback forms or the pods principal funder of located around the foyers. the Barbican Centre Welcome Tonight we welcome back Harry Bicket as delighted by the extravagant magical and The English Concert for Rinaldo, the effects as by Handel’s endlessly inventive latest instalment in their Handel opera music. And no wonder – for Rinaldo brings series. Last season we were treated to a together love, vengeance, forgiveness, spine-tingling performance of Ariodante, battle scenes and a splendid sorceress with a stellar cast led by Alice Coote. -

DISTRICT AUDITIONS THURSDAY, JANUARY 21, 2021 the 2020 National Council Finalists Photo: Fay Fox / Met Opera

NATIONAL COUNCIL 2020–21 SEASON ARKANSAS DISTRICT AUDITIONS THURSDAY, JANUARY 21, 2021 The 2020 National Council Finalists photo: fay fox / met opera CAMILLE LABARRE NATIONAL COUNCIL AUDITIONS chairman The Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions program cultivates young opera CAROL E. DOMINA singers and assists in the development of their careers. The Auditions are held annually president in 39 districts and 12 regions of the United States, Canada, and Mexico—all administered MELISSA WEGNER by dedicated National Council members and volunteers. Winners of the region auditions executive director advance to compete in the national semifinals. National finalists are then selected and BRADY WALSH compete in the Grand Finals Concert. During the 2020–21 season, the auditions are being administrator held virtually via livestream. Singers compete for prize money and receive feedback from LISETTE OROPESA judges at all levels of the competition. national advisor Many of the world’s greatest singers, among them Lawrence Brownlee, Anthony Roth Costanzo, Renée Fleming, Lisette Oropesa, Eric Owens, and Frederica von Stade, have won National Semifinals the Auditions. More than 100 former auditioners appear appear on the Met roster each season. Sunday, May 9, 2021 The National Council is grateful to its donors for prizes at the national level and to the Tobin Grand Finals Concert Endowment for the Mrs. Edgar Tobin Award, given to each first-place region winner. Sunday, May 16, 2021 Support for this program is generously provided by the Charles H. Dyson National Council The Semifinals and Grand Finals are Audition Program Endowment Fund at the Metropolitan Opera. currently scheduled to take place at the Met. -

The Pamphilj and the Arts

The Pamphilj and the Arts Patronage and Consumption in Baroque Rome aniè C. Leone Contents Preface 7 Acknoweedgments 9 Introduction 11 Stephanie C. Leone The Four Rivers Fountain: Art and Buieding Technoeogy in Pamphiei Rome 23 Maria Grazia D Amelio and Tod A. Marder The Aedobrandini Lunettes: from Earey Baroque Chapee Decoration to Pamphiej Art Treasures 37 Catherine Pnglisi Cannocchiaei Pamphiej per ee steeee, per i quadri e per tutto ie resto 47 Andrea G. De Marchi Committenze artistiche per ie matrimonio di Anna Pamphiej e Giovanni Andrea III Doria Landi (1671) 55 Lanra Stagno Notes on Aeessandro Stradeeea, L’avviso al Terrò giunto 77 Carolyn Giantnrco and Eleanor F. McCrickard L’avviso al Terrò giunto (Onge Tirer had reen apprised) 78 Alessandro Stradella The Jesuit Education of Benedetto Pamphiej at the Coeeegio Romano 85 Pani F. Grendler Too Much a Prince to be but a Cardinae: Benedetto Pamphiej and the Coeeege of Cardinaes in the Age of the Late Baroque 95 James M. Weiss Cardinae Benedetto Pamphiej’s Art Coeeection: Stiee-eife Painting and the Cost of Coeeecting 113 Stephanie C. Leone Cardinae Benedetto Pamphiej and Roman Society: Pestivaes, Peases, and More 139 Daria Borghese Benedetto Pamphiej’s Suneeower Carriage and the Designer Giovanni Paoeo Schor 151 Stefanie Walker Le conversazioni in musica: Cargo Prancesco Cesarini, virtuoso di Sua Ecceeeenza Padrone 161 Alexandra Nigito Pamphiej as Phoenix: Themes of Resurrection in Handee’s Itaeian Works 189 Ellen T. Harris The Power of the Word in Papae Rome: Pasquinades and Other Voices of Dissent 199 Lanrie Shepard “PlORlSCONO Dl SPEENDORE EE DUE COSPICUE LIBRARIE DEE SIGNOR CARDINAEE BENEDETTO PaMEIEIO”: STUDI E RICERCHE SUGEI INVENTARI INEDITI Dl UNA PERDUTA BiBEIOTECA 211 Alessandra Mercantini Appendice.