Megalethoscope Plates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Still Photography

Still Photography Soumik Mitra, Published by - Jharkhand Rai University Subject: STILL PHOTOGRAPHY Credits: 4 SYLLABUS Introduction to Photography Beginning of Photography; People who shaped up Photography. Camera; Lenses & Accessories - I What a Camera; Types of Camera; TLR; APS & Digital Cameras; Single-Lens Reflex Cameras. Camera; Lenses & Accessories - II Photographic Lenses; Using Different Lenses; Filters. Exposure & Light Understanding Exposure; Exposure in Practical Use. Photogram Introduction; Making Photogram. Darkroom Practice Introduction to Basic Printing; Photographic Papers; Chemicals for Printing. Suggested Readings: 1. Still Photography: the Problematic Model, Lew Thomas, Peter D'Agostino, NFS Press. 2. Images of Information: Still Photography in the Social Sciences, Jon Wagner, 3. Photographic Tools for Teachers: Still Photography, Roy A. Frye. Introduction to Photography STILL PHOTOGRAPHY Course Descriptions The department of Photography at the IFT offers a provocative and experimental curriculum in the setting of a large, diversified university. As one of the pioneers programs of graduate and undergraduate study in photography in the India , we aim at providing the best to our students to help them relate practical studies in art & craft in professional context. The Photography program combines the teaching of craft, history, and contemporary ideas with the critical examination of conventional forms of art making. The curriculum at IFT is designed to give students the technical training and aesthetic awareness to develop a strong individual expression as an artist. The faculty represents a broad range of interests and aesthetics, with course offerings often reflecting their individual passions and concerns. In this fundamental course, students will identify basic photographic tools and their intended purposes, including the proper use of various camera systems, light meters and film selection. -

Gallery Text That Accompanies This Exhibition In

Steeped in the classical training of an English gentleman, Edward Dodwell (1777/78– 1832) first traveled through Greece in 1801. He returned in 1805 in the company of an Italian artist, Simone Pomardi (1757–1830), and together they toured the country for fourteen months, drawing and documenting the landscape with exacting detail. They produced around a thousand illustrations, most of which are now in the collection of the Packard Humanities Institute in Los Altos, California. A selection from this rich archive is presented here for the first time in the United States. Dodwell and Pomardi frequently used a camera obscura, an optical device that made it easier to create accurate images. Beyond providing evidence for the appearance of monuments and vistas, their illustrations manifest the ideal of the picturesque that enraptured so many European travelers. The sight of ancient temples lying in ruin, or of the Greek people under Turkish rule as part of the Ottoman Empire, prompted meditation on the transience of human accomplishments. As Dodwell himself wrote: “When we contemplated the scene around us, and beheld the sites of ruined states, and kingdoms, and cities, which were once elevated to a high pitch of prosperity and renown, but which have now vanished like a dream . we could not but forcibly feel that nations perish as well as individuals.” Dodwell’s own words accompany the majority of images in this exhibition. His descriptions are drawn from his Classical and Topographical Tour through Greece, during the Years 1801, 1805, and 1806 (London, 1819). The author’s original spelling, capitalization, and punctuation have been retained. -

Elements of Screenology: Toward an Archaeology of the Screen 2006

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Erkki Huhtamo Elements of screenology: Toward an Archaeology of the Screen 2006 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/1958 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Huhtamo, Erkki: Elements of screenology: Toward an Archaeology of the Screen. In: Navigationen - Zeitschrift für Medien- und Kulturwissenschaften, Jg. 6 (2006), Nr. 2, S. 31–64. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/1958. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under a Deposit License (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, non-transferable, individual, and limited right for using this persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses document. This document is solely intended for your personal, Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für non-commercial use. All copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute, or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the conditions of vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder use stated above. anderweitig nutzen. Mit der Verwendung dieses Dokuments erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen an. -

Colour Relationships Using Traditional, Analogue and Digital Technology

Colour Relationships Using Traditional, Analogue and Digital Technology Peter Burke Skills Victoria (TAFE)/Italy (Veneto) ISS Institute Fellowship Fellowship funded by Skills Victoria, Department of Innovation, Industry and Regional Development, Victorian Government ISS Institute Inc MAY 2011 © ISS Institute T 03 9347 4583 Level 1 F 03 9348 1474 189 Faraday Street [email protected] Carlton Vic E AUSTRALIA 3053 W www.issinstitute.org.au Published by International Specialised Skills Institute, Melbourne Extract published on www.issinstitute.org.au © Copyright ISS Institute May 2011 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Whilst this report has been accepted by ISS Institute, ISS Institute cannot provide expert peer review of the report, and except as may be required by law no responsibility can be accepted by ISS Institute for the content of the report or any links therein, or omissions, typographical, print or photographic errors, or inaccuracies that may occur after publication or otherwise. ISS Institute do not accept responsibility for the consequences of any action taken or omitted to be taken by any person as a consequence of anything contained in, or omitted from, this report. Executive Summary This Fellowship study explored the use of analogue and digital technologies to create colour surfaces and sound experiences. The research focused on art and design activities that combine traditional analogue techniques (such as drawing or painting) with print and electronic media (from simple LED lighting to large-scale video projections on buildings). The Fellow’s rich and varied self-directed research was centred in Venice, Italy, with visits to France, Sweden, Scotland and the Netherlands to attend large public events such as the Biennale de Venezia and the Edinburgh Festival, and more intimate moments where one-on-one interviews were conducted with renown artists in their studios. -

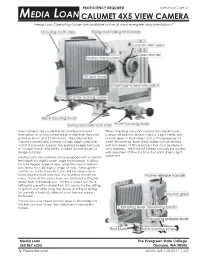

Basic View Camera

PROFICIENCY REQUIRED Operating Guide for MEDIA LOAN CALUMET 4X5 VIEW CAMERA Media Loan Operating Guides are available online at www.evergreen.edu/medialoan/ View cameras are usually tripod mounted and lend When checking out a 4x5 camera from Media Loan, themselves to a more contemplative style than the more patrons will need to obtain a tripod, a light meter, one portable 35mm and 2 1/4 formats. The Calumet 4x5 or both types of film holders, and a changing bag for Standard model view camera is a lightweight, portable sheet film loading. Each sheet holder can be loaded tool that produces superior, fine grained images because with two sheets of film, a process that must be done in of its large format and ability to adjust for a minimum of total darkness. The Polaroid holders can only be loaded image distortion. with one sheet of film at a time, but each sheet is light Media Loan's 4x5 cameras come equipped with a 150mm protected. lens which is a slightly wider angle than normal. It allows for a 44 degree angle of view, while the normal 165mm lens allows for a 40 degree angle of view. Although the controls on each of Media Loan's 4x5 lens may vary in terms of placement and style, the functions remain the same. Some of the lenses have an additional setting for strobe flash or flashbulb use. On these lenses, use the X setting for use with a strobe flash (It’s crucial for the setting to remain on X while using the studio) and the M setting for use with a flashbulb (Media Loan does not support flashbulbs). -

Calumet's Digital Guide to View Camera Movements

Calumet’sCalumet’s DigitalDigital GuideGuide ToTo ViewView CameraCamera MovementsMovements Copyright 2002 by Calumet Photographic Duplication is prohibited under law Calumet Photographic Chicago IL. Copies may be obtained by contacting Richard Newman @ [email protected] What you can expect to find inside 9 Types of view cameras 9 Necessary accessories 9 An overview of view camera lens requirements 9 Basic view camera movements 9 The Scheimpflug Rule 9 View camera movements demonstrated 9 Creative options There are two Basic types of View Cameras • Standard “Rail” type view camera advantages: 9 Maximum flexibility for final image control 9 Largest selection of accessories • Field or press camera advantages: 9 Portability while maintaining final image control 9 Weight Useful and necessary Accessories 9 An off camera meter, either an ambient or spot meter. 9 A loupe to focus the image on the ground glass. 9 A cable release to activate the shutter on the lens. 9 Film holders for traditional 4x5 film holder image capture. 9 A Polaroid back for traditional test exposures, to check focus or final art. VIEW CAMERA LENSES ARE DIVIDED INTO THREE GROUPS, WIDE ANGLE, NORMAL AND TELEPHOTO WIDE ANGLES LENSES WOULD BE FROM 38MM-120MM FOCAL LENGTHS FROM 135-240 WOULD BE CONSIDERED NORMAL TELEPHOTOS COULD RANGE FROM 270MM-720MM FOR PRACTICAL PURPOSES THE FOCAL LENGTHS DISCUSSED ARE FOR 4X5” FORMAT Image circle- The black lines are the lens with no tilt and the red lines show the change in lens coverage with the lens tilted. If you look at the film plane, you can see that the tilted lens does not cover the film plane, the image circle of the lens is too small with a tilt applied to the camera. -

Features of Mamiya RB 67

INSTRUCTIONS Congratulations on your pur chase of a Mamiya RB67 camera. Reading this manual carefully before· hand will ensure correct camera opera· tion and eliminate any possibility of malfunction. The Mamiya RB67 camera is part of a 'unique camera system, developed by the Mamiya Camera Company, the re· cognized world leader in large format photography. It takes its place alongside the famous Mamiya C Professional and the Mamiya Press cameras. The versatility of the Mamiya RB67, embodying fine performance and various capabilities, results in a large format camera that meets and satisfies all the requirements of the advanced amateur as weil as the professional photographer. Its interlocking use of many Mamiya Press camera accessories further widens its range of photographic application. • Special Pointers in Using the Mamiya RB 67 Under any of the following conditions the cameras safety interlock mechanism will engage. This may seem to be a ca me ra malfunction. A few of these conditions are listed below. The page in the instruction manual covering these situations is indicated in parenthesis. Condition: Shutter release button will not release. 1. When the mirror is up: Press the shutter cocking lever (pg. 12). 2 . When the dark slide is not pulled out: Pull out the dark slide (pg. 18). 3 . When the shutter release button is locked: Turn the shutter release lock ring counterclockwise (pg. 12). 4 . When the revolving adapter is not turned fully to the click stop position: Turn the revolving adapter a full 90° until it clicks and stops (pg. 14). 5 . When the slide lock is stopped halfway:. -

SHOOTING the BIG BERTHA by Geoffrey Berliner

SHARING INFORMATION ABOUT GRAFLEX AND THEIR CAMERAS ISSUE 2, 2016 FEATURES This was not a problem, because I had the needed shut- ter speed to shoot wide open. Shooting the Big Bertha by Geoffrey Berliner……………………….……..………1 Mine Is Bigger Than Yours by Ken Metcalf……...………………………...……...2 This April I had the wonderful experience shooting the From Chicago to Rochester via Delaware the Cee-ay by Michael Parker..…...6 Big Bertha on opening day at Yankee Stadium. There Graflex R.B. Series D User-Friendly Modifications by Randy Sweatt……...…...8 was a learning curve using the camera, but my many LE-2(2) by Jim Chasse……………………………………………………………...11 years of experience using Graflex SLR cameras and my experience shooting large format certainly helped in making the shoot a success. Here are some quotes from the opening day program: “Using mid-20th century cam- eras, Yankees Magazine captures opening day in a whole SHOOTING THE BIG BERTHA new light. On Opening Day this season, we decide to meld the past and the present. Thanks to a loan from the By Geoffrey Berliner Penumbra Foundation, Yankee Magazine photographers [and I] captured the scene at Yankee Stadium on April 5 using the same type of Graflex cameras that Joe Di- Mr. Berliner is the Executive Director of New York City's Maggio and Mickey Mantle once posed for.” Penumbra Foundation www.penumbrafoundation.org, an- tique camera lens collector (with over 1,500 lenses), GHQ contributor and Graflex camera collector. The Penumbra Foundation is a non-profit organization that brings together the art and science of photography through education, re- search, outreach, public and residency programs. -

Gibson + Recoder: Powers of Resolution Cinema Arts Essays / 1

GIBSON + RECODER: POWERS OF RESOLUTION CINEMA ARTS ESSAYS / 1 Gibson + Recoder: Powers of Resolution is part of the project Lightplay organized by Cinema Arts at the Exploratorium. This project is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts. Powers of Resolution is an exhibition that resolves upon the optical properties of both natural and artificial Obscurus Projectum analog film objects encompasses the whimsical and the melancholy, About the Artists light. Natural light in Obscurus Projectum is the incandescent light reflected from the objective field, a tiny the elegant and the (pleasingly) clunky, showcasing the special Sandra Gibson and Luis Recoder stage the scene of film as orphaned By Jonathan Walley fraction of which makes its way into a dark theater, reconstituting the rays in the form of a moving penumbra qualities of analog, mechanical, photochemical, celluloid film. One object through the temporal labor of a moving image installation. on a large screen. Artificial light in Illuminatoria is the refracted light that ricochets from the transparent of those special qualities is that analog cameras and projectors Collaborators since 2000, Gibson and Recoder unite the rich medium of various rotating glass elements, recasting the play of light into an abstract moving canvas on the open up to let us in, figuratively at least. A malfunctioning digital traditions of experimental film, particularly its structuralist and back side of a translucent portal. The dark chambers enclosing the two installations disclose the cinematic camera will not reveal what ails it to the curious user who opens it materialist strands, and the multimodal sensibility of expanded precondition for the resolving power of light. -

Big Bertha/Baby Bertha

Big Bertha /Baby Bertha by Daniel W. Fromm Contents 1 Big Bertha As She Was Spoke 1 2 Dreaming of a Baby Bertha 5 3 Baby Bertha conceived 8 4 Baby Bertha’s gestation 8 5 Baby cuts her teeth - solve one problem, find another – and final catastrophe 17 6 Building Baby Bertha around a 2x3 Cambo SC reconsidered 23 7 Mistakes/good decisions 23 8 What was rescued from the wreckage: 24 1 Big Bertha As She Was Spoke American sports photographers used to shoot sporting events, e.g., baseball games, with specially made fixed lens Single Lens Reflex (SLR) cameras. These were made by fitting a Graflex SLR with a long lens - 20" to 60" - and a suitable focusing mechanism. They shot 4x5 or 5x7, were quite heavy. One such camera made by Graflex is figured in the first edition of Graphic Graflex Photography. Another, used by the Fort Worth, Texas, Star-Telegram, can be seen at http://www.lurvely.com/photo/6176270759/FWST_Big_Bertha_Graflex/ and http://www.flickr.com/photos/21211119@N03/6176270759 Long lens SLRs that incorporate a Graflex are often called "Big Berthas" but the name isn’t applied consistently. For example, there’s a 4x5 Bertha in the George Eastman House collection (http://geh.org/fm/mees/htmlsrc/mG736700011_ful.html) identified as a "Little Bertha." "Big Bertha" has also been applied to regular production Graflexes, e.g., a 5x7 Press Graflex (http://www.mcmahanphoto.com/lc380.html ) and a 4x5 Graflex that I can’t identify (http://www.avlispub.com/garage/apollo_1_launch.htm). These cameras lack the usual Bertha attributes of long lens, usually but not always a telephoto, and rapid focusing. -

Graphic Materials: Rules for Describing Original Items and Historical Collections

GRAPHIC MATERIALS Rules for Describing Original Items and Historical Collections compiled by Elisabeth W. Betz Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., 1982 WordPerfect version 6/7/8 (July 2000; with MARC21 tagging added March 2002) With cumulated updates: 1982-1996 and List of areas to update for second edition: 1997-2000 Cover illustration: "Sculptor. Der Formschneider." Woodcut by Jost Amman in Hartmann Schopper's Panoplia, omnium illiberalium mechanicarum aut sedentariarum artium genera continens, printed at Frankfurt am Main by S. Feyerabent, 1568. Rosenwald Collection, Rare Book and Special Collections Division. (Neg. no. LC-USZ62-44613) TABLE OF CONTENTS Graphic Materials (1996-1997 Updates)...................p. i Issues to consider for second edition (1997-2000).......p. iii Preface.................................................p. 1 Introduction............................................p. 3 0. General Rules........................................p. 8 0A. Scope.............................................p. 8 0B. Sources of information............................p. 9 0C. Punctuation.......................................p. 10 0D. Levels of description.............................p. 12 0E. Language and script of the description............p. 13 0F. Inaccuracies......................................p. 14 0G. Accents and other diacritical marks (including capitalization)..................................p. 14 0H. Abbreviations, initials, etc......................p. 14 0J. Interpolations....................................p. 15 1. -

TESSERACT -- Antique Scientific Instruments

TESSERACT Early Scientific Instruments Special Issue: OPTICAL PLEASURES Catalogue One Hundred Seven Summer, 2018 $10 CATALOGUE ONE HUNDRED SEVEN Copyright 2018 David Coffeen CONDITIONS OF SALE All items in this catalogue are available at the time of printing. We do not charge for shipping and insurance to anywhere in the contiguous 48 states. New York residents must pay applicable sales taxes. For buyers outside the 48 states, we will provide packing and delivery to the post office or shipper but you must pay the actual shipping charges. Items may be reserved by telephone, and will be held for a reasonable time pending receipt of payment. All items are offered with a 10-day money-back guarantee for any reason, but you pay return postage and insurance. We will do everything possible to expedite your shipment, and can work within the framework of institutional requirements. The prices in this catalogue are net and are in effect through December, 2018. Payments by check, bank transfer, or credit card (Visa, Mastercard, American Express) are all welcome. — David Coffeen, Ph.D. — Yola Coffeen, Ph.D. Members: Scientific Instrument Society American Association for the History of Medicine Historical Medical Equipment Society Antiquarian Horological Society International Society of Antique Scale Collectors Surveyors Historical Society Early American Industries Association The Oughtred Society American Astronomical Society International Coronelli Society American Association of Museums Co-Published : RITTENHOUSE: The Journal of the American Scientific Instrument Enterprise (http://www.etesseract.com/RHjournal/) We are always interested in buying single items or collections. In addition to buying and selling early instruments, we can perform formal appraisals of your single instruments or whole collections, whether to determine fair market value for donation, for insurance, for loss, etc.