THE GRAPHIC 35 ELECTRIC by Michael Parker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Still Photography

Still Photography Soumik Mitra, Published by - Jharkhand Rai University Subject: STILL PHOTOGRAPHY Credits: 4 SYLLABUS Introduction to Photography Beginning of Photography; People who shaped up Photography. Camera; Lenses & Accessories - I What a Camera; Types of Camera; TLR; APS & Digital Cameras; Single-Lens Reflex Cameras. Camera; Lenses & Accessories - II Photographic Lenses; Using Different Lenses; Filters. Exposure & Light Understanding Exposure; Exposure in Practical Use. Photogram Introduction; Making Photogram. Darkroom Practice Introduction to Basic Printing; Photographic Papers; Chemicals for Printing. Suggested Readings: 1. Still Photography: the Problematic Model, Lew Thomas, Peter D'Agostino, NFS Press. 2. Images of Information: Still Photography in the Social Sciences, Jon Wagner, 3. Photographic Tools for Teachers: Still Photography, Roy A. Frye. Introduction to Photography STILL PHOTOGRAPHY Course Descriptions The department of Photography at the IFT offers a provocative and experimental curriculum in the setting of a large, diversified university. As one of the pioneers programs of graduate and undergraduate study in photography in the India , we aim at providing the best to our students to help them relate practical studies in art & craft in professional context. The Photography program combines the teaching of craft, history, and contemporary ideas with the critical examination of conventional forms of art making. The curriculum at IFT is designed to give students the technical training and aesthetic awareness to develop a strong individual expression as an artist. The faculty represents a broad range of interests and aesthetics, with course offerings often reflecting their individual passions and concerns. In this fundamental course, students will identify basic photographic tools and their intended purposes, including the proper use of various camera systems, light meters and film selection. -

Photo History Newsletters • Vol

THE AMALGAMATED PHOTO HISTORY NEWSLETTERS • VOL. 2-2 2021 We hope that the Covid pandemic soon passes away so we can get back to normal with regular meetings and events. In the interim here are addi- tional newsletters to keeping you read- ing. Please enjoy. Ken Metcalf of the Graflex Journal has another interesting issue which should entertain you well. Another fine newsletter comes from The Western Canada Photographic Historical Association in British Colum- bia with some fine reading content. Permissions granted: Graflex Journal– Ken Melcalf The Western Canada Photographic Historical Association– Tom Parkinsion SHARING INFORMATION ABOUT GRAFLEX AND THEIR CAMERAS ISSUE 3 2020 FEATURES some leather that was a good match. Thickness was right, color was good, and the pebble grain was close National Graflex Gets a New Coat by Paul S. Lewis……..….....….....….1 enough. So, I had them send me a large sheet; 12x17. Camera Group - Roger Beck………….…….………...….…..…………....2 Having a good supply would allow for some mistakes Viewing Wild Animals at Night by William V. Ward …….…...…………..4 and assure me that there would be enough length and Hold It! Part 1 by Ken Metcalf.……………….…………….…………….....5 width to cover the missing panels with one complete Graflex Patents by Joel Havens….…..………………...…………….…...12 piece. The source I used was Cameraleather ([email protected]). I did just check with them to be sure similar material is available. The report is that although the material is available, supply is limited. So, with material and camera in hand, the next step Ed: Mr. Lewis is a Graflex Journal subscriber and author was to get the new cover panels cut out and attached. -

Graflex Historic Quarterly the Quarterly Is Dedicated to Enriching the Study of the Graflex Company, Its History, and Products

G RAFLEX Since 1996 HISTORIC QUARTERLY VOLUME 19 ISSUE 1 FIRST QUARTER 2014 FEATURES Arthur L. Princehorn Arthur L. Princehorn and His Camera by Ken Metcalf with Linda Grimm……………………………………………………...……...1 Linda Grimm writes that in the fall of 1894, Arthur L. Prince- Two Graflex Home Portrait Bodies Made for Big Bertha Use by Doug horn set out from Ohio for New Rochelle, New York, with Frank……………………………………………………………....6 his bride, Agnes, to begin a new career as a photographer and Reviews: Mizu-san, SHORPY and PhotoHistory XVI....………..….….7 naturalist at John H. Starin’s Glen Island Resort. There he Chicken or the Egg...or Evolved Chicken?.....…………………………………………..8 joined his former Oberlin College colleague, Lewis M. McCormick, in a program to develop a natural history mu- seum at the famous family day resort on Long Island Sound. The skills they brought were honed in the college museum and included mounting specimens (taxidermy), maintaining displays, and organizing materials for laboratory classes. In addition, they both had years of experience as amateur field naturalists and shared an avid interest in photography. This was a rare opportunity for two very talented young men, and by all indications they made a great success of it over the ten- year period they worked at Glen Island. The museum grew year-by-year as Lewis gathered material on trips to distant locales in Europe, Africa, the Middle East, Asia, and the Pa- cific. They continued to prepare specimens from the local area and develop exhibits to excite the public’s interest in natural history. Mr. Princehorn increasingly used photogra- phy in his work, seeking images of animals in both natural and captive settings. -

I. Basic Operation (Preparation)

10 lcon indicators used in this manual BASIC OPERATION (PREPARATION) BASIC OPERATION Operation direction Attention Lamp blinking I. BASIC OPERATION (PREPARATION) Attaching the Camera Strap 11 123 BASIC OPERATION (PREPARATION) BASIC OPERATION 1. Use a coin or similar object to slide the clasp 3. To remove the strap, repeat step 1. in the direction of the arrow. 2. Put the clasp onto the strap lug of the cam- • Adjust the length of the strap with the buckle. era with the arrow indication facing out, and • After fitting the strap and adjusting the length, pull slide the lock plate back to the original posi- the strap hard to confirm that the strap has tion. securely attached to the camera. • There is a pocket on the strap so you can store a small accessory. 12 Loading the Batteries 123 BASIC OPERATION (PREPARATION) BASIC OPERATION 1. To remove the battery holder, lift the battery 3. To secure the battery holder, turn the battery holder release knob and turn it in the direc- holder release knob in the direction of the tion of the arrow. arrow. 2. Load six 1.5V AA-size batteries in the battery holder in accordance with the diagram located in the battery holder. 13 • This camera requires battery power for operation. Always use six 1.5V AA size batteries. • The ISO film speed and number of exposed frames are unchanged if the batteries are replaced. (PREPARATION) BASIC OPERATION • Keep spare batteries on hand when shooting out doors or while traveling. • Use of the optional Remote Battery Pack 645 is recommended when the camera is used in extremely low temperatures. -

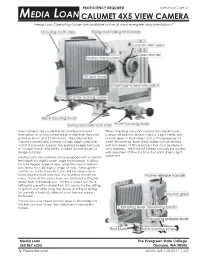

Basic View Camera

PROFICIENCY REQUIRED Operating Guide for MEDIA LOAN CALUMET 4X5 VIEW CAMERA Media Loan Operating Guides are available online at www.evergreen.edu/medialoan/ View cameras are usually tripod mounted and lend When checking out a 4x5 camera from Media Loan, themselves to a more contemplative style than the more patrons will need to obtain a tripod, a light meter, one portable 35mm and 2 1/4 formats. The Calumet 4x5 or both types of film holders, and a changing bag for Standard model view camera is a lightweight, portable sheet film loading. Each sheet holder can be loaded tool that produces superior, fine grained images because with two sheets of film, a process that must be done in of its large format and ability to adjust for a minimum of total darkness. The Polaroid holders can only be loaded image distortion. with one sheet of film at a time, but each sheet is light Media Loan's 4x5 cameras come equipped with a 150mm protected. lens which is a slightly wider angle than normal. It allows for a 44 degree angle of view, while the normal 165mm lens allows for a 40 degree angle of view. Although the controls on each of Media Loan's 4x5 lens may vary in terms of placement and style, the functions remain the same. Some of the lenses have an additional setting for strobe flash or flashbulb use. On these lenses, use the X setting for use with a strobe flash (It’s crucial for the setting to remain on X while using the studio) and the M setting for use with a flashbulb (Media Loan does not support flashbulbs). -

Perfection V500 Photo

Epson Perfection V500 Photo Scanner Parts Optional Automatic Document Feeder The Automatic Document Feeder (B12B813391) allows you to Scanner cover automatically load multiple-page documents into your scanner. See the on-screen User’s Guide for instructions on installing and using the optional Automatic Document Feeder (ADF). Scan to PDF button Automatic Document Feeder Scan to Power switch E-mail button Copy button Start button Paper support Holds up the paper that is loaded in the ADF. Document mat Transparency unit Carriage transportation lock Spare paper path guide Document table The paper path guide directs documents smoothly onto the scanner's document table. A spare paper path guide is included. If the surface of the paper path guide gets dirty, you can clean it or replace it with the spare guide. Scanner OPTION port transportation lock USB interface DC inlet connector ADF Document Mat Place this mat over a document if you need to scan it from the document table when the ADF is installed. Cover cable (Transportation unit) 7/07 Epson Perfection V500 Photo - 1 Epson Perfection V500 Photo Electrical Scanner Specifications Note: Check the label on the AC adapter or on the back of the scanner for General voltage information. Scanner type Flatbed color Scanner Photoelectric device Color CCD line sensor Rated voltage DC 24 V Effective pixels 54,400 × 74,880 pixels at 6400 dpi* Rated current 1.3 A Scanning area may be restricted if Power consumption 16.0 W (17.5 W with ADF) operating resolution setting is large. 7.5 (6.5 W with ADF) ready -

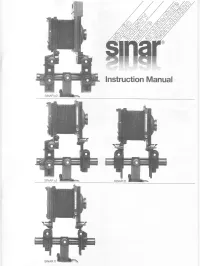

Manual Sinar P2 / C2 / F2 / F1-EN (PDF)

lnstructionManual The cameras Operatingcontrols of the SINAR iT p2andc2 1 Coarse-focusclamping lever 2 Finefocusing drive with depth of field scale 3 Micrometer drive for vertical (rise and fall) shift 4 Micrometer drive for lateral(cross) shift 5 Micrometerdrive for horizontal-axistilts 6 Micrometer drive for vertical-axisswings 7 lmageplane mark 8 Coarse-tilt (horizontal axis) clamping lever; movementused for verticalalignment of stan- dards with camerainclined up or down, alsofor coarse tilting to reservefull micrometertilt (5) rangefor sharpnessdistribution control. Fig.1 Contents The cameras 2 The planeof sharpnessand depthof field 11 - Controls 2 - Zerosettings Fufiher accessories 12 3 - - Mountingthe camera SINARCOLOR CONTROLfitters 12 4 - - The spirit levels Exposure meters 12 4 - - The base rail 4 AutomaticSINAR film holder - Changingcomponents 4 and shuttercoupling 12 - Film - The bellows 5 holders 13 - Camera backs s Final points 14 - Switchingformats p2 on the STNAR andc2 6 - Maintenance 14 - Switchingformats g on the SINARf2 andtl - Cleaning 14 - The convertible g camera - Adjusting the drives 14 - The bellowshood 9 - Cleaninglenses, filters and mirrors 14 - Viewingaids 9 - Warranty 14 - Transport l0 - Furtherinstruction manuals 14 The view camera movements 10 Remark: The camerac2 is no longerpart of the SINARsales programme, but can stiltrbe combined by the individualSINAR components. Operatingcontrols of the S|NARt2andtl 1 Coarse-focusclamping knob 2 Finefocussing drive with depthof fieldscale 3 Clampingwheel for verticalshift 4 Clampinglever for lateralshift 5 Clampinglever for swing (verticalaxis) 6 Clampinglever for tilt (horizontalaxis) 7 Angle-meteringscale for tilt and swingangles 8 lmageplane mark Zero setting points of the cameras CAMERAMODELS REAR(IMAGE) STANDARD FRONT(LENS) STANDARD NOTES SINARo2 With regularor special gxi|2 - 4x5 / White l White White dot for standardbearer 5x7 /13x18 Green i dots White lateralshift on With F/S back j or. -

EPSON SCANNING TIPS and TROUBLESHOOTING GUIDE Epson Perfection 3170 Scanner

EPSON SCANNING TIPS AND TROUBLESHOOTING GUIDE Epson Perfection 3170 Scanner SELECT A SUITABLE RESOLUTION The best scanning resolution depends on the purpose of the scan. When you specify a high resolution, the number of pixels increases and the scanned image becomes finer in texture. However, increasing the resolution causes the file size to increase. For example, an 8.5 x 11-inch original scanned at 300 dpi can produce a 24MB file. The same original scanned at 72 dpi creates only a 1.3MB file. Large files take longer to process and print, so select the lowest possible resolution that produces acceptable quality. Specify a suitable resolution according to your scanning purpose. Recommended resolutions for scanning print material: PURPOSE RESOLUTION Web pages 96 dpi Sending E-mail 96 to 150 dpi Printing 300 dpi Saving as a PDF file 300 dpi Sending Fax 200 dpi OCR (Optical Character Recognition) 300 dpi Use Target Size to specify the output size of the scanned image. If you are enlarging your image, you must increase the resolution (dpi) proportionally to maintain the resolution of your original. Try scanning slides at 1200 dpi or higher. If you reduce the size of the image on a page, it does not decrease its file size. SCAN SETTINGS For photos: For film: For slides: Specify Adjustment settings, if necessary, such as dust removal for slides and film. PLACING FILM OR SLIDES ON SCANNER You can scan 35mm slides, 35mm film or negative strips, and Medium Format transparencies on the Epson 3170 using the appropriate film holders which come with the scanner. -

GRAFLEX F'~- '3F/Uueu«J ~ with the NEW Ektalite Field Lens GRAFLEX CAMERAS OFFER YOU ALL THESE ADVANTAGES

GRAFLEX f'~- '3f/UueU«J ~ with the NEW Ektalite Field Lens GRAFLEX CAMERAS OFFER YOU ALL THESE ADVANTAGES: • A Sing le Lens System Free From Parallax • Full Vision Ground Glass Focusing • W ide Range, High Speed Focal Plane Shutter • Interchangeability of Lenses • Revolving Back • Interchangeable Film Attachments PLUS The Ektalite Field Lens-Newest aid for better pictures The GRAFLEX Single Lens Reflex at Work ... 1. As you look into the focusing hood you see on the ground glass, up to the instant of exposure, a brilliant, reflected image, right side-up and full picture size, revealing exactly the sharpness of focus and composition of the subject matter that will be recorded on the film. 2. When the pleasingly composed image is clear on the ground glass, the subject is in sharp focus. 3. The mirror reflects the image to the ground glass. When the exposure release is pressed, the mirror swings upward out of the way, instantly releasing the focal plane shutter-securing the desired picture. 4. Focusing is under convenient, positive control to the very instant of exposure. 5. Superior lens gathers ample light for the focal plane shutter, which transmits appreciably more light than does any other type of shutter. Since the lens through which you focused is the lens which makes the picture, it entirely elim inates any problem of parallax. 2U. x 3U. REVOLVING BACK GRAFLEX CAMERA ~S(J~l'ake 9M S(J 9~ '[)~I OMPLETE with standard Graflex fea a complete range of speeds from 1/10 to C tures this camera is a favorite among 1/1000. -

Photography Lab Cookbook

Photography Lab Cookbook Table of Contents. 1. Photo lab SOP 2. Photo lab Manuals 3. Film Processes E-6 Processing Procedure E-6 Chemical Mixing instruction Black and White Chemistry Development 4. Paper Processing Black and White Paper Development Porta-Mixer Black and White Core & Close-up Photo Distribution 5. Close-up Photography Introduction Talk with Scientist Close up photography Close up spreadsheet master Close-up request sheet 6. Silk Screening Procedure 7. Silk Screen Flyers (see separate files) Logos due T-shirts due Name on shirt Light Ink Dark Ink Iron Shirts 8. Photographic Examples (see separate files) Group Photo Tech Photo Mug Shots Cookbook– Photo Lab 1 PHOTO LAB STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURE (SOP) PORTCALL (on coming) Onboard ship: • Find off going Marine Lab Specialist’s, Photo Lab and begin X-over. X-over • Read lab reports from previous leg. • Discuss with off going marine specialist any changes in equipment status, software or procedures. • Check supply levels in photo lab and hold refer. You are responsible for this inventory. Estimate amount of film, paper and chemistry needed for each particular type of leg. If you do not feel you have enough supplies necessary (after checking oncoming shipments), notify LO to purchase film/paper/chemistry in port. • You are responsible for knowing the status of ALL equipment in your lab by the end of the x- over. If you need additional days to complete your x-over, notify the LO ASAP so that arrangements can be made. Other: • Assist with loading/unloading freight and other tasks as directed by LO/ALO. -

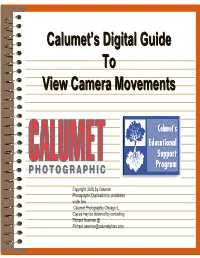

Calumet's Digital Guide to View Camera Movements

Calumet’sCalumet’s DigitalDigital GuideGuide ToTo ViewView CameraCamera MovementsMovements Copyright 2002 by Calumet Photographic Duplication is prohibited under law Calumet Photographic Chicago IL. Copies may be obtained by contacting Richard Newman @ [email protected] What you can expect to find inside 9 Types of view cameras 9 Necessary accessories 9 An overview of view camera lens requirements 9 Basic view camera movements 9 The Scheimpflug Rule 9 View camera movements demonstrated 9 Creative options There are two Basic types of View Cameras • Standard “Rail” type view camera advantages: 9 Maximum flexibility for final image control 9 Largest selection of accessories • Field or press camera advantages: 9 Portability while maintaining final image control 9 Weight Useful and necessary Accessories 9 An off camera meter, either an ambient or spot meter. 9 A loupe to focus the image on the ground glass. 9 A cable release to activate the shutter on the lens. 9 Film holders for traditional 4x5 film holder image capture. 9 A Polaroid back for traditional test exposures, to check focus or final art. VIEW CAMERA LENSES ARE DIVIDED INTO THREE GROUPS, WIDE ANGLE, NORMAL AND TELEPHOTO WIDE ANGLES LENSES WOULD BE FROM 38MM-120MM FOCAL LENGTHS FROM 135-240 WOULD BE CONSIDERED NORMAL TELEPHOTOS COULD RANGE FROM 270MM-720MM FOR PRACTICAL PURPOSES THE FOCAL LENGTHS DISCUSSED ARE FOR 4X5” FORMAT Image circle- The black lines are the lens with no tilt and the red lines show the change in lens coverage with the lens tilted. If you look at the film plane, you can see that the tilted lens does not cover the film plane, the image circle of the lens is too small with a tilt applied to the camera. -

Features of Mamiya RB 67

INSTRUCTIONS Congratulations on your pur chase of a Mamiya RB67 camera. Reading this manual carefully before· hand will ensure correct camera opera· tion and eliminate any possibility of malfunction. The Mamiya RB67 camera is part of a 'unique camera system, developed by the Mamiya Camera Company, the re· cognized world leader in large format photography. It takes its place alongside the famous Mamiya C Professional and the Mamiya Press cameras. The versatility of the Mamiya RB67, embodying fine performance and various capabilities, results in a large format camera that meets and satisfies all the requirements of the advanced amateur as weil as the professional photographer. Its interlocking use of many Mamiya Press camera accessories further widens its range of photographic application. • Special Pointers in Using the Mamiya RB 67 Under any of the following conditions the cameras safety interlock mechanism will engage. This may seem to be a ca me ra malfunction. A few of these conditions are listed below. The page in the instruction manual covering these situations is indicated in parenthesis. Condition: Shutter release button will not release. 1. When the mirror is up: Press the shutter cocking lever (pg. 12). 2 . When the dark slide is not pulled out: Pull out the dark slide (pg. 18). 3 . When the shutter release button is locked: Turn the shutter release lock ring counterclockwise (pg. 12). 4 . When the revolving adapter is not turned fully to the click stop position: Turn the revolving adapter a full 90° until it clicks and stops (pg. 14). 5 . When the slide lock is stopped halfway:.