Partogram Use in the Dar Es Salaam Perinatal Care Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

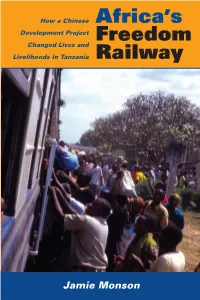

Africa's Freedom Railway

AFRICA HistORY Monson TRANSPOrtatiON How a Chinese JamiE MONSON is Professor of History at Africa’s “An extremely nuanced and Carleton College. She is editor of Women as On a hot afternoon in the Development Project textured history of negotiated in- Food Producers in Developing Countries and Freedom terests that includes international The Maji Maji War: National History and Local early 1970s, a historic Changed Lives and Memory. She is a past president of the Tanzania A masterful encounter took place near stakeholders, local actors, and— Studies Assocation. the town of Chimala in Livelihoods in Tanzania Railway importantly—early Chinese poli- cies of development assistance.” the southern highlands of history of the Africa —James McCann, Boston University Tanzania. A team of Chinese railway workers and their construction “Blessedly economical and Tanzanian counterparts came unpretentious . no one else and impact of face-to-face with a rival is capable of writing about this team of American-led road region with such nuance.” rail power in workers advancing across ’ —James Giblin, University of Iowa the same rural landscape. s Africa The Americans were building The TAZARA (Tanzania Zambia Railway Author- Freedom ity) or Freedom Railway stretches from Dar es a paved highway from Dar Salaam on the Tanzanian coast to the copper es Salaam to Zambia, in belt region of Zambia. The railway, built during direct competition with the the height of the Cold War, was intended to redirect the mineral wealth of the interior away Chinese railway project. The from routes through South Africa and Rhodesia. path of the railway and the After being rebuffed by Western donors, newly path of the roadway came independent Tanzania and Zambia accepted help from communist China to construct what would together at this point, and become one of Africa’s most vital transportation a tense standoff reportedly corridors. -

Kilombero Plantations Limited

KILOMBERO PLANTATIONS LIMITED MNGETA FARM SQUATTER SURVEY REPORT Claude G. Mung’ong’o, PhD and Juma Kayonko, MSc Natural Resource Management Consultants P.O. Box 35097, Dar es Salaam FEBRUARY 2009 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION Background Located in Mngeta Division, Kilombero District, Mngeta Farm (5,818 ha) is owned by Kilombero Plantations Ltd (KPL), a public-private partnership between the Rufiji Basin Development Authority (RUBADA) and InfEnergy Tanzania Ltd. In 1986, the Government of Tanzania granted the farm area to the Korea Tanzania Agricultural Company (KOTACO), a Korea – Tanzania government partnership. KOTACO surveyed the farm, cleared the entire 5818 ha, and built 185 km of roads and approximately 290 km of drainage ditches. KOTACO farmed rice on approximately 2500 ha until 1993 when the Koreans left the project and handed over the farm equipment and infrastructure to RUBADA. From 1994 to 1999 the farm remained idle. Later in 1999 RUBADA contracted the farm to Kilombero Holding Company (KIHOCO) which never farmed more than 400 ha. KIHOCO fell 5 years behind in rent payments and was finally forced off the farm in August 2007. During the period of the farm’s idleness it attracted a gradual influx of subsistence squatters from different parts of Tanzania. It also attracted a high influx of livestock, especially from 2005 onwards. In December 2007, KPL began operations, re-clearing land and planting 641 ha of rice in early 2008. In September 2008 KPL completed the title transfer of Mngeta Farm. KPL is planting 3000 ha of rice in early 2009 and has targeted 5800 ha of rice in 2010. -

USAID Boresha Afya - Southern Zone September 2019 Newsletter

Issue #6 USAID Boresha Afya - Southern Zone September 2019 Newsletter Content Foreword Program highlights Success stories Page 02 As our Program moves On 9 July 2019, the Charge According to the Tanzania past the half way stage of d’affaires (CDA) of the HIV Impact Survey (2016 – implementation, there are United States Embassy in 2017), Lindi region has a low plenty....... Tanzania.......... HIV.................... Page 04 Page 06 Page 18 Achieving our vision USAID Boresha Afya Southern Zone Newsletter | Issue 06 | September 2019 USAID Boresha Afya Southern Zone Newsletter | Issue 06 | September 2019 Contents 14 Jan - Feb 19 Index Cascade 12 12 11 11 10 8 7 6 6 6 4 2 2 1 0 Jan - 19 Feb - 19 Index clients No of sexual partner elicited Tested pos 04 06 10 14 Foreword Program highlights Program highlights Success Stories – Collaboration of Partners Impresses – Program Collaborates with Media to – Optimization of Positive Case CDA upon Visit to Ifakara Health Document Progress in Malaria Identification through Index Testing Institute at Ruangwa District Hospital – Lindi Region 16 18 20 22 Success Stories Success Stories Success Stories Success Stories – Changing Roles: Data Clerks Fostering – How the SMS Reminder System is – Mlimba Health Centre, a Beacon of – Testimonials Data Quality and Data Use for Decision Reshaping HIV/AIDS Services in Tanzania: Excellence in Index Testing. Making A Case Study of USAID Boresha Afya – Southern Zone, Njombe Region. 2 3 USAID Boresha Afya Southern Zone Newsletter | Issue 06 | September 2019 USAID Boresha Afya Southern Zone Newsletter | Issue 06 | September 2019 Foreword Dear Friends of USAID Boresha Afya – Southern Zone As our Program moves past the half I would be remiss if I did not take way stage of implementation, there a moment to acknowledge that are plenty of achievements to write all Program achievements owe a about. -

Small Farmer Productivity Through Increased Access to Draught Power Opportunities

MOVEK Development Solution SMALL FARMER PRODUCTIVITY THROUGH INCREASED ACCESS TO DRAUGHT POWER OPPORTUNITIES Consultancy Report Stakeholder mapping in Morogoro region December 2008 (Final Report) ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. The Department for International Development (DfID has been a major supporter of natural resource research through its Renewable Natural Resource Research Strategy (RNRRS) which ran from 1995 to 2006. The results realized through such initiatives have enormous potential to alleviate poverty, promote economic growth, and mitigate the environmental problem. Unfortunately these efforts were not able to produce the expected results. 2. Within this reality, Research Into Use (RIU) programme has been conceived to meet this challenge. The approach used by RIU programme is slightly different from previous approaches since it has shifted its emphasis away from the generation of new knowledge to the ways in which knowledge is put into productive use 3. To complement the innovation system, the RIU programme intended to work with a network of partners (innovation platforms) working on common theme and using research knowledge in ways it hasn’t been used before to generate improved goods and services for the benefit of the poor. 4. To start the RIU programme in Tanzania identified three innovation platforms, three farm products in three regions as pilot domains. One of the platforms is access to draught power which is thought to enhance productivity of small holder farmers through increased access to and capacity to utilize draught power opportunities in Ulanga, Kilombero, Kilosa, and Mvomero districts 5. This report is based on the findings of the mapping study conducted in Ulanga, Kilombero, Kilosa and Mvomero districts which overlaped to Morogoro municipality 6. -

Morogoro Health Abstract 2005/2006

ISBN 9987-9087-1-3 The United Republic of Tanzania Prime Minister’s Office Regional Administration and Local Government Morogoro Region MOROGORO HEALTH ABSTRACT 2005/2006 June 2006 Morogoro Health Project April 2001 – March 2007 The United Republic of Tanzania Prime Minister’s Office Regional Administration and Local Government Morogoro Region MOROGORO HEALTH ABSTRACT 2005/2006 Morogoro Health Abstract was produced by the collaboration of Tanzanian and Japanese experts with Financial Assistance and Technical Cooperation to Morogoro Region by Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). i Contents Page • Foreword ii • Statement From Morogoro Health Project Chief Advisor iii • Acknowledgement v • Abbreviations and Acronyms vi • Executive Summary viii Chapter I. Introduction 1 Chapter II. Health Mapping 4 Chapter III. Basic Abstracts 7 III.1 Human Resources Information 7 III.2 Health Facilities Information 8 III.3 Health Services Information 11 III.4 Diseases Information 18 III.5 Health Commodities Information 31 III.6 Health Management Information 33 Chapter VI. Focused Abstracts 34 Chapter V. Integrated Supportive Supervision 36 Annexes (I – IX) come after page 38 In Future Issue: Health Trends will start: • Trend of Human Resources in Morogoro Region • Trend of HF Distribution in Morogoro Region • Trend of Disease Distribution in Morogoro Region • Trend of Health Budget in Morogoro Region MHA 2005/2006 ii FOREWORD The Morogoro Regional Secretariat welcomes the Morogoro Health Abstract [MHA]. We believe that the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare will also appreciate that their concept of introducing Health Statistics Abstract has given an offspring in one of the Regions in the country. The Morogoro Health Abstract 2005/2006 is a summary of selected health statistical information available in the Region at the time of the preparation of the Abstract, that is 2006 June. -

MOROGORO MALARIA in PREGNANCY

MOROGORO NEWSLETTER Vol. No. 1 July 2003 MMMALARIA in PREGNANCY Malaria, which is transmitted by anopheles mosquito, causes high morbidity and mortality in pregnant mothers and children under five years. Over 30 percent of the total outpatients in health facilities are suffering from malaria. Malaria in pregnant mothers can cause the following problems: z Anaemia z Stillbirth z Low birth weight deliveries (less than 2.5 kg) z Premature delivery z Miscarriage z Maternal death Pregnant mothers receiving health education. Pregnant mothers are advised to attend antenatal clinics during the early stage of pregnancy, Insecticide Treated Nets (ITNs) are sold at a preferably before 20-weeks. At the clinics, they will discounted price to pregnant mothers at many be advised and provided with preventive drugs clinics. The aforementioned services are available including those against Malaria. During antenatal at all antenatal clinics in Morogoro Region. clinics, pregnant mothers are examined and Ms. N. A. Ahmed Nursing Officer, investigated. Any illnesses detected are treated in Health Department, Morogoro Municipality order to protect the mother and the expected child. - In This Issue – One of the drugs recommended for the treatment z Malaria in Pregnancy ---- p.1 of malaria to a pregnant mother is a combination of Sulphadoxine and Pymethamine (SP) in the z Greetings: Regional Administrative Secretariat ---- p.2 schedule prescribed below: - st z Congratulation: Regional Medical Officer ---- p.2 z 20 – 24 weeks pregnancy, 1 dose. nd z z 28 – 32 weeks pregnancy, 2 dose. The Editorial Morogoro health Newsletter ---- p.3 NOTE: The SP should not be taken at the same z The Regional Health Meeting ---- p.4 time with folic acid because SP will not be z Community Participation ---- p.4 effective in that case. -

Mlimba Institute of Health and Allied Sciences (Mihas)

MLIMBA INSTITUTE OF HEALTH AND ALLIED SCIENCES (MIHAS) P. O. Box 64, Mlimba-Ifakara-Morogoro – Tanzania Tel +255 621119544, +255 767550766/ 0718240555 Website: www.mihas.ac.tz E-mail: [email protected] JOINING INSTRUCTION FOR ACADEMIC YEAR 2021/2022 Date: …05/06/2021…. Our Ref. MIHAS/ADMN/20/…….. Dear: ………………………………………. …….. ……………………………………………………… ……………………………………………………… STUDENTS JOINING INSTRUCTIONS FOR TECHNICIAN CERTIFICATE AND ORDINARY DIPLOMA IN CLINICAL MEDICINE, ACADEMIC YEAR 2021/2022. Please refer to your application for admission into Ordinary Diploma in Clinical Medicine programme for academic year 2021/2022. I am pleased to inform you that your application has been successfully. Congratulations for being selected and thank you for choosing Mlimba Institute of health and Allied Sciences (MIHAS). The academic year will commence on 11th October, 2021. Enclosed herewith are instructions provided for your guidance and you are requested to read them very carefully before you come to the college. Upon arrival you will be issued with Student’s By- Laws, which cover more fully the regulations governing your stay at MIHAS You are required to confirm acceptance of this offer by sending the short message to 0718240555/0621119544 for reservation of your vacancy. All selected Candidates are advised to pay the fee through College bank accounts and come with bank pay slip during arrival to avoid money loss. All payments should be made through Account No. CRDB NO. 0150431072400 with the name MLIMBA INST OF HLTH AND ALIED SCIENCE for Tuition Fee and Account No. NMB 24410002185 with the name MLIMBA INST OF HLTH AND ALIED SCIENCE for other charges. th NOTE: Registration period will commence on 11 October 2021 to 18th October 2021. -

FIELD RECONNAISSANCE REPORT Kilombero Valley Irrigation Schemes

FIELD RECONNAISSANCE REPORT Kilombero Valley Irrigation Schemes: 10-14 December 2012 Technical Assistance to Support the Development of Irrigation and Rural Roads Infrastructure Project (IRRIP2) January 2013 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by CDM International Inc. FIELD RECONNAISSANCE REPORT Kilombero Valley Irrigation Schemes: 10-14 December 2012 Technical Assistance to Support the Development of Irrigation and Rural Roads Infrastructure Project (IRRIP2) Prepared by: Keith F. Williams, P.E., Chief of Party Organization: CDM International, Inc. (CDM Smith) Submitted to: Robert Pierce, United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Contracting Officer’s Representative (COR) USAID Contract No.: EDH-I-00-08-00023-00, Task Order AID-621-TO-12-00002 Report Date: 09 January 2013 DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. ES EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ES.1 Background Under the U.S. Government’s Feed the Future (FTF) program, CDM International Inc. (CDM Smith) is implementing USAID/Tanzania’s Technical Assistance to Support the Development of Irrigation and Rural Roads Infrastructure Project (IRRIP21). Among other activities, IRRIP2 is supporting the development of irrigation schemes in the Kilombero district of Morogoro region. This report covers the activities and findings of a week-long field trip to the four IRRIP 2 irrigation areas in the Kilombero Valley between 10 and 14 December 2012. Each project area was visited and meetings held with all the key village councils. The Zonal Irrigation Office (ZIO) within the Ministry of Agriculture, Food Security and Cooperatives (MAFC) generated rapid appraisal documents for each of the schemes between 2006 and 2010. -

Cepf Small Grant Final Project Completion Report

CEPF SMALL GRANT FINAL PROJECT COMPLETION REPORT I. BASIC DATA Organization Legal Name: WWF Tanzania Programme Office Project Title: Socio-Economic Study of the Udzungwa Scarp Area: A Potential Wildlife Corridor Implementation Partners for This Project: Project Dates (as stated in the grant agreement): February 1, 2006 - July 30, 2006 Date of Report (month/year): February 2007 II. OPENING REMARKS The report gives a summary of the Socio-economic issues for villages around Udzungwa Scarp, Iyondo, Matundu, Nyanganje, Ihanga and Iwonde forest reserves and the ‘Idete corridor’ forests. The villages covered were Signali, Kiberege Ihanga, Machipi, Kilama, Igima, Mpofu, Mngeta, Njage, Idete Namawala, Mkangawalo, Ikule, Chita and Udagaji . Generating socio-economic information for incorporating livelihood assessments and options for future management of Udzungwa Forests was one of the priority interventions identified during the Stakeholders consultative workshop held in December 2004 at Oasis Hotel in Morogoro region, Tanzania. The project was addressing CEPF Strategic Direction 1 and 2 namely Increase the ability of local populations to benefit from, and contribute to biodiversity conservation and enhancing connectivity among fragmented forest patches in the hotspot in and around Udzungwa. Udzungwa Scarp Forest Reserve, Iyondo, Matundu, Nyanganje Ihanga, Iwonde forest reserves and the ‘Idete corridor’ forests form a network of the largest forest blocks of the Udzungwa Mountains of Tanzania. The mountainous ranges contain the greatest coverage of moist forest within the Eastern Arc Mountains that are recognized as part of a globally outstanding biodiversity hotspot together with Coastal forests of Tanzania and Kenya. Besides their biological importance, the reserves contribute significantly to people’s livelihoods and socio-economic development of the country. -

Title CONFLICTS OVER LAND and WATER RESOURCES IN

CONFLICTS OVER LAND AND WATER RESOURCES IN Title THE KILOMBERO VALLEY FLOODPLAIN, TANZANIA Nindi, Stephen Justice; Maliti, Hanori; Bakari, Samwel; Kija, Author(s) Hamza; Machoke, Mwita African study monographs. Supplementary issue (2014), 50: Citation 173-190 Issue Date 2014-10 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.14989/189720 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, Suppl. 50: 173–190, October 2014 173 CONFLICTS OVER LAND AND WATER RESOURCES IN THE KILOMBERO VALLEY FLOODPLAIN, TANZANIA Stephen Justice Nindi(1) Hanori Maliti(1) Samwel Bakari(1) Hamza Kija(1) Mwita Machoke(1) (1)Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute ABSTRACT The Kilombero Valley fl oodplain (KVFP) inhabits a very large natural wetland of which over 70% is protected. Diverse mammals, amphibians, fi sh and bird species populate the area. Importantly, KVFP harbours 75% of the world Puku antelope population. Most human activities in the area include large and small scale farming, pastoralism and fi shing. Recently, population pressure, overgrazing and aligned human activities have pressed strain on the land and water resources in the KVFP. The situation prompted the government of Tanzania to resettle some of the pastoral families so as to achieve sustainable natural resources management. The paper provides an insight of this resettlement exercise as a multi- layered land use confl ict and its effects to the land resources and people’s livelihoods. Focused group discussions, key informant interviews both using checklists and literature review were the methods used for data collection. The Sukuma agro-pastoralists, Maasai and Barbaig pastoralists were the most ethnic groups affected by the resettlement exercise. -

Africa in Transition Micro Study Tanzania

AFRICA IN TRANSITION MICRO STUDY TANZANIA Research Report Prepared by: Gasper C. Ashimogo Aida C. Isinika James E.D. Mlangwa July 2003 Table of contents 1. METHODOLOGY ..................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Introduction......................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Selection of Districts................................................................................................. 5 1.3 Selection of Villages................................................................................................. 5 1.4. Selection of household for the village diagnostics questionnaire............................ 7 1.5 Selection of household for the household survey questionnaire............................... 7 2. THE VILLAGE DIAGNOSTICS SURVEY RESULTS ........................................... 9 2.1 Agricultural dynamism ....................................................................................... 9 2.1.1 Population size, land use and agro-ecology................................................ 9 2.1.2 Infrastructure and market access............................................................... 10 2.2 State initiatives.................................................................................................. 11 2.3 Markets ............................................................................................................. 13 2.4 Farmer organisations........................................................................................ -

The Impact of Migrant Livestock Keepers on the Natives and Natural Resources of Kilombero Valley, in Tanzania: a Case of Kilombero District

THE IMPACT OF MIGRANT LIVESTOCK KEEPERS ON THE NATIVES AND NATURAL RESOURCES OF KILOMBERO VALLEY, IN TANZANIA: A CASE OF KILOMBERO DISTRICT By Alto Mbikiye Kabuye Dissertation Submitted in Partial/fulfillment of the Requirements for the Award of the Masters of Science in Development Policy (MSc. DP) of Mzumbe University 2015 CERTIFICATION We, the undersigned, certify that we have read and hereby recommend for acceptance by Mzumbe University, a dissertation entitled “The Impact of Migrant Livestock keepers on the natives and Natural Resources of the Kilombero Valley in Tanzania: The Case of Kilombero District” in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Masters of Science in Development Policy (MSc. DP) offered by Mzumbe University. ………………………………………………… Major Supervisor …………………………………………………. Internal Examiner Accepted for the Board of Institute of Development Studies ------------------------------------------------- DIRECTOR, INSTITUTE OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES DECLARATION AND COPYRIGHT I, Alto Mbikiye Kabuye declare that, this dissertation is my original work and that; it has not been presented and will not be presented to any other University for a similar or any other degree award. Signature: …………………………………………. Date: ……………………………................…….. ©2015 This dissertation is a copyright material protected under the Berne Convention, the copyright Act 1999 and other international and national enactments, in that behalf, on intellectual property. It may not be reproduced by any means in full or in part, except for short extracts in fair dealings, for research or private study, critical scholarly review or discourse with an acknowledgment, without the written permission of Mzumbe University, on behalf of the author ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, all praise and gratefulness is due to Almighty God who endowed me with strength, health, patience, and knowledge to complete this work.