Local History and Community Action in Modern Metropolitan Chicago

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SUSTAINABILITY CIES 2019 San Francisco • April 14-18, 2019 ANNUAL CONFERENCE PROGRAM RD 6 3

EDUCATION FOR SUSTAINABILITY CIES 2019 San Francisco • April 14-18, 2019 ANNUAL CONFERENCE PROGRAM RD 6 3 #CIES2019 | #Ed4Sustainability www.cies.us SUN MON TUE WED THU 14 15 16 17 18 GMT-08 8 AM Session 1 Session 5 Session 10 Session 15 8 - 9:30am 8 - 9:30am 8 - 9:30am 8 - 9:30am 9 AM Coffee Break, 9:30am Coffee Break, 9:30am Coffee Break, 9:30am Coffee Break, 9:30am 10 AM Pre-conference Workshops 1 Session 2 Session 6 Session 11 Session 16 10am - 1pm 10 - 11:30am 10 - 11:30am 10 - 11:30am 10 - 11:30am 11 AM 12 AM Plenary Session 1 Plenary Session 2 Plenary Session 3 (includes Session 17 11:45am - 1:15pm 11:45am - 1:15pm 2019 Honorary Fellows Panel) 11:45am - 1:15pm 11:45am - 1:15pm 1 PM 2 PM Session 3 Session 7 Session 12 Session 18 Pre-conference Workshops 2 1:30 - 3pm 1:30 - 3pm 1:30 - 3pm 1:30 - 3pm 1:45 - 4:45pm 3 PM Session 4 Session 8 Session 13 Session 19 4 PM 3:15 - 4:45pm 3:15 - 4:45pm 3:15 - 4:45pm 3:15 - 4:45pm Reception @ Herbst Theatre 5 PM (ticketed event) Welcome, 5pm Session 9 Session 14 Closing 4:30 - 6:30pm 5 - 6:30pm 5 - 6:30pm 5 - 6:30pm Town Hall: Debate 6 PM 5:30 - 7pm Keynote Lecture @ Herbst 7 PM Theatre (ticketed event) Presidential Address State of the Society Opening Reception 6:30 - 9pm 6:45 - 7:45pm 6:45 - 7:45pm 7 - 9pm 8 PM Awards Ceremony Chairs Appreciation (invite only) 7:45 - 8:30pm 7:45 - 8:45pm 9 PM Institutional Receptions Institutional Receptions 8:30 - 9:45pm 8:30 - 9:45pm TABLE of CONTENTS CIES 2019 INTRODUCTION OF SPECIAL INTEREST Conference Theme . -

Illinois Assembly on Political Representation and Alternative Electoral Systems I 3 4 FOREWORD

ILLINOIS ASSEMBLY ON POLITICAL REPRESENTATION AND ALTERNATIVE # ELECTORAL SYSTEMS FINAL REPORT AND BACKGROUND PAPERS ILLINOIS ASSEMBLY ON POLITICAL REPRESENTATION AND ALTERNATIVE #ELECTORAL SYSTEMS FINAL REPORT AND BACKGROUND PAPERS S P R I N G 2 0 0 1 2 CONTENTS Foreword...................................................................................................................................... 5 Jack H. Knott I. Introduction and Summary of the Assembly Report ......................................................... 7 II. National and International Context ..................................................................................... 15 An Overview of the Core Issues ....................................................................................... 15 James H. Kuklinski Electoral Reform in the UK: Alive in ‘95.......................................................................... 17 Mary Georghiou Electoral Reform in Japan .................................................................................................. 19 Thomas Lundberg 1994 Elections in Italy .........................................................................................................21 Richard Katz New Zealand’s Method for Representing Minorities .................................................... 26 Jack H. Nagel Voting in the Major Democracies...................................................................................... 30 Center for Voting and Democracy The Preference Vote and Election of Women ................................................................. -

JOURNAL of the PROCEEDINGS of the CITY COUNCIL of the CITY of CHICAGO, ILLINOIS

(Published by the Authority of the City Council of the City of Chicago) COPY JOURNAL of the PROCEEDINGS of the CITY COUNCIL of the CITY of CHICAGO, ILLINOIS Inaugural Meeting -- Monday, May 20, 2019 at 10:30 AM. (Wintrust Arena -- Chicago, Illinois) OFFICIAL RECORD. LORI E. LIGHTFOOT ANDREA M. VALENCIA Mayor City Clerk 5/20/2019 INAUGURAL MEETING 1 MUSICAL PRELUDE. The Chicago Gay Men's Chorus, led by Artistic Director Jimmy Morehead, performed a series of musical selections including "World". The ensemble from the Puerto Rican Arts Alliance, led by Founder and Executive Director Carlos Hernandez-Falcon, performed a series of musical selections. The After School Matters Choir, led by Directors Daniel Henry and Jean Hendricks, performed a series of musical selections including "Bridge Over Troubled Water'' and "Rise Up". The Native American Veterans Group of Trickster Art Gallery, led by Courte Tribe and Chief Executive Officer Joseph Podlasek Ojibwe Lac Oreilles, and the Ribbon Town Drum from Pokagon Band of Potawatomi performed the ceremony dedication. The Merit School of Music, comprised of Joshua Mhoon, piano, and Steven Baloue, violin, performed a musical selection. Chicago Sinfonietta -- Project Inclusion, led by Executive Director Jim Hirsch and comprised of Danielle Taylor, violin; Fahad Awan, violin; Seth Pae, viola; and Victor Sotelo, cello, performed a series of musical selections, including "At Last" and "Chicago". INTRODUCTION OF 2019 -- 2023 CITY COUNCIL MEMBERS-ELECT. Each of the members-elect of the 2019 -- 2023 City Council of Chicago was introduced as they entered the arena. INTRODUCTION OF SPECIAL GUESTS. The following special guests were introduced: Mr. -

Village of Algonquin Annual Budget: FY 16/17

Annual Budget May 1, 2016 - April 30, 2017 Adopted April 5, 2016 A Glimpse into Algonquin’s History… The Village of Algonquin was settled in 1834 with the arrival of Samuel Gillian, the first settler in McHenry County. Other early settlers were Dr. Cornish, Dr. Plumleigh, Eli Henderson, Alex Dawson, and William Jackson. The Village changed names several times in the early days; the names included Cornish Ferry, Cornishville, and Osceola. The name Algonquin was finally selected in 1847 as a suggestion from Samuel Edwards as a namesake for a ship he once owned. The Village was incorporated in 1890 and witnessed both commercial and recreational trade. Algonquin was a favorite vacation spot for residents of Chicago. Nestled in the foothills of the Fox River Valley, Algonquin became known as the “Gem of the Fox River Valley.” The first Village Hall was constructed in 1906 at 2 South Main Street and throughout the years housed fire protection, library, and school services for the community as well as accommodating the municipal offices. The building served as Village Hall until the new Village Hall was completed in 1996. The original building is now called Historic Village Hall and serves as a community facility and meeting location. A highlight in Algonquin’s history was the period from 1906 to 1913, when the Algonquin Hill Climbs were held. The event was one of the earliest organized auto racing events held in the United States. Algonquin had a population of about 600 residents at that time and the annual hill climbs would bring crowds in excess of 25,000 to the Village. -

Torture in Chicago

TORTURE IN CHICAGO A supplementary report on the on-going failure ofgovernment officials to adequately deal with the scandal October 29, 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION.................................................................................... 3 THE FEDERAL INVESTIGATION... 5 ILLINOIS ATTORNEY GENERAL AND TORTURE VICTIMS WHO REMAIN IMPRISONED.......................................................................................... 8 THE CITY OF CHICAGO... 10 Compensation, Reparations, and Treatment for Torture Victims.................. 14 The Darrell Cannon Case... 14 Reparations and Treatment.................................................................. 18 COOK COUNTY AND THE COOK COUNTY STATE'S ATTORNEYS' OFFICE ... 20 INTERNATIONAL ACTIONS, HEARINGS AND REPORTS.................. 24 STATE AND FEDERAL LEGISLATION......................................................... 26 THE FRATERNAL ORDER OF POLICE... 27 CONCLUSION AND CALL TO ACTION..................... 28 SIGNATURES....................................... 29 2 I believe that were this to take place in any other city in America, it would be on the front page ofevery major newspaper. Andthis is obscene and outrageous that we're even having a discussion today about the payment that is due the victims oftorture. I think in light ofwhat has happened at Abu Ghraib, in Iraq with respect to torture victims, I am shocked and saddened at the fact that we are having to engage in hearings such as these . ... We need to stop with this nonsense. I join with my colleagues in saying this has got to stop. Alderman Sandi Jackson, Chicago City Council Hearing on Police Torture, July 24, 2007 **** This was a serial torture operation that ran out ofArea 2...The pattern was there. Everybody knew what was going on. ... [Elverybody in this room, everybody in this building, everybody in the police department, everybody in the State's Attorney's office, would like to get this anvil ofJon Burge offour neck andI think that there are creative ways to do that. -

National News in ‘09: Obama, Marriage & More Angie It Was a Year of Setbacks and Progress

THE VOICE OF CHICAGO’S GAY, LESBIAN, BI AND TRANS COMMUNITY SINCE 1985 Dec. 30, 2009 • vol 25 no 13 www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com Joe.My.God page 4 LGBT Films of 2009 page 16 A variety of events and people shook up the local and national LGBT landscapes in 2009, including (clockwise from top) the National Equality March, President Barack Obama, a national kiss-in (including one in Chicago’s Grant Park), Scarlet’s comeback, a tribute to murder victim Jorge Steven Lopez Mercado and Carrie Prejean. Kiss-in photo by Tracy Baim; Mercado photo by Hal Baim; and Prejean photo by Rex Wockner National news in ‘09: Obama, marriage & more Angie It was a year of setbacks and progress. (Look at Joining in: Openly lesbian law professor Ali- form for America’s Security and Prosperity Act of page 17 the issue of marriage equality alone, with deni- son J. Nathan was appointed as one of 14 at- 2009—failed to include gays and lesbians. Stone als in California, New York and Maine, but ad- torneys to serve as counsel to President Obama Out of Focus: Conservative evangelical leader vances in Iowa, New Hampshire and Vermont.) in the White House. Over the year, Obama would James Dobson resigned as chairman of anti-gay Here is the list of national LGBT highlights and appoint dozens of gay and lesbian individuals to organization Focus on the Family. Dobson con- lowlights for 2009: various positions in his administration, includ- tinues to host the organization’s radio program, Making history: Barack Obama was sworn in ing Jeffrey Crowley, who heads the White House write a monthly newsletter and speak out on as the United States’ 44th president, becom- Office of National AIDS Policy, and John Berry, moral issues. -

Burris, Durbin Call for DADT Repeal by Chuck Colbert Page 14 Momentum to Lift the U.S

THE VOICE OF CHICAGO’S GAY, LESBIAN, BI AND TRANS COMMUNITY SINCE 1985 Mar. 10, 2010 • vol 25 no 23 www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com Burris, Durbin call for DADT repeal BY CHUCK COLBERT page 14 Momentum to lift the U.S. military’s ban on Suzanne openly gay service members got yet another boost last week, this time from top Illinois Dem- Marriage in D.C. Westenhoefer ocrats. Senators Roland W. Burris and Richard J. Durbin signed on as co-sponsors of Sen. Joe Lie- berman’s, I-Conn., bill—the Military Readiness Enhancement Act—calling for and end to the 17-year “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” (DADT) policy. Specifically, the bill would bar sexual orien- tation discrimination on current service mem- bers and future recruits. The measure also bans armed forces’ discharges based on sexual ori- entation from the date the law is enacted, at the same time the bill stipulates that soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Coast Guard members previ- ously discharged under the policy be eligible for re-enlistment. “For too long, gay and lesbian service members have been forced to conceal their sexual orien- tation in order to dutifully serve their country,” Burris said March 3. Chicago “With this bill, we will end this discrimina- Takes Off page 16 tory policy that grossly undermines the strength of our fighting men and women at home and abroad.” Repealing DADT, he went on to say in page 4 a press statement, will enable service members to serve “openly and proudly without the threat Turn to page 6 A couple celebrates getting a marriage license in Washington, D.C. -

Collection Overview

Archives Collections Guide Updated March 28, 2016 Collection Overview The Gerber/Hart archives focuses its collections on gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and queer life in the Chicago metropolitan area and the Midwest. It contains over 150 collections of historically significant personal manuscripts, photographs, audiovisual recordings, and organizational records. These collections include unpublished material such as letters, diaries, and scrapbooks documenting the lives of both average people and community leaders. They also include the records of many community organizations, businesses, and political campaigns. This guide is intended to serve as a preliminary research tool that provides a brief description of holdings with basic information on size, inclusive dates, types of records, and broad subject areas. Guide Contents List of Collections..............................................................................................................................................2 Collections Descriptions....................................................................................................................................6 Name Index......................................................................................................................................................26 Topical Index...................................................................................................................................................34 1 Archives Collections Guide Updated March 28, 2016 List of Collections -

Allyson Hobbs Cv June 2020

June 2020 ALLYSON VANESSA HOBBS Department of History, Stanford University 450 Serra Mall, Building 200, Stanford, CA 94305 [email protected] allysonhobbs.com CURRENT POSITIONS Stanford University, Associate Professor, Department of History, September 2008 - present Director, African and African American Studies, January 2017 – present Kleinheinz Family University Fellow in Undergraduate Education, 2019-2024 Affiliated with: American Studies (Committee-in-Charge Member) Center for Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity (Core Affiliated Faculty) Center for Spatial and Textual Analysis (Researcher) Center for Institutional Courage (Research Advisor) Ethics in Society (Faculty Affiliate) Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies (Program Committee) Masters in Liberal Arts Program (Faculty Advisor) Michelle R. Clayman Institute for Gender Research (Faculty Fellow) Stanford Center for Law and History (Affiliated Member) Urban Studies (Faculty Affiliate) The New Yorker.com, Contributing Writer, November 2015 – present https://www.newyorker.com/contributors/allyson-hobbs EDUCATION University of Chicago, Ph.D., History, March 2009, with distinction Dissertation: “When Black Becomes White: The Problem of Racial Passing in American Life” Committee: Professors Thomas Holt (Chair; History, University of Chicago), George Chauncey (History, Yale University), Jacqueline Stewart (Cinema and Media Studies, University of Chicago) Harvard University, A.B., Social Studies, June 1997, magna cum laude Received magna cum laude distinction on senior honors -

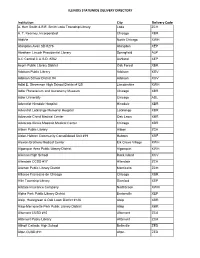

Illinois Statewide Delivery Directory

ILLINOIS STATEWIDE DELIVERY DIRECTORY Institution City Delivery Code A. Herr Smith & E.E. Smith Loda Township Library Loda ZCH A. T. Kearney, Incorporated Chicago XBR AbbVie North Chicago XWH Abingdon-Avon SD #276 Abingdon XEP Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library Springfield ALP A-C Central C.U.S.D. #262 Ashland XEP Acorn Public Library District Oak Forest XBR Addison Public Library Addison XGV Addison School District #4 Addison XGV Adlai E. Stevenson High School District #125 Lincolnshire XWH Adler Planetarium and Astronomy Museum Chicago XBR Adler University Chicago ADL Adventist Hinsdale Hospital Hinsdale XBR Adventist LaGrange Memorial Hospital LaGrange XBR Advocate Christ Medical Center Oak Lawn XBR Advocate Illinois Masonic Medical Center Chicago XBR Albion Public Library Albion ZCA Alden-Hebron Community Consolidated Unit #19 Hebron XRF Alexian Brothers Medical Center Elk Grove Village XWH Algonquin Area Public Library District Algonquin XWH Alleman High School Rock Island XCV Allendale CCSD #17 Allendale ZCA Allerton Public Library District Monticello ZCH Alliance Francaise de Chicago Chicago XBR Allin Township Library Stanford XEP Allstate Insurance Company Northbrook XWH Alpha Park Public Library District Bartonville XEP Alsip, Hazelgreen & Oak Lawn District #126 Alsip XBR Alsip-Merrionette Park Public Library District Alsip XBR Altamont CUSD #10 Altamont ZCA Altamont Public Library Altamont ZCA Althoff Catholic High School Belleville ZED Alton CUSD #11 Alton ZED ILLINOIS STATEWIDE DELIVERY DIRECTORY AlWood CUSD #225 Woodhull -

475 Ethics Ordinance List As of February 2006

475 Ethics Ordinance List as of February 2006 CITY OF CHICAGO 475 Ethics Ordinance List of Vendors who have received from City of Chicago payments totaling $10,000 or more in any 12 - month period over the past four reporting years VENDOR NAME VENDOR ADDRESS "READING IN MOTION" 65 E WACKER DR 1800 EFT, CHICAGO, IL 60601 #2 MT. PLEASANT M.B. CHURCH 947 N CICERO AVE, CHICAGO, IL 60651 (ULI) URBAN LAND INSTITUTE 1025 THMS JEFFERSON ST NW 500, WASHINGTON, DC 20007-5201 100 NORTH RIVERSIDE LLC 455 N CITYFRONT PLAZA DR, CHICAGO, IL 60611 1134-36 W. BRYN MAWR LLC 1134-1136 W BRYN MAWR AVE, CHICAGO, IL 60640 119TH ST. & DAN RYAN/URBAN 41 W CONGRESS PKWY, SUITE 100, CHICAGO, IL 60605 1325 WILSON LLC C/O MID LAKES MANAGEMENT LLC, 166 W. WASHINGTON #300, CHICAGO, IL 60602 1456 BIRCHWOOD LLC 1456 W. BIRCHWOOD, CHICAGO, IL 60626 14TH PLACE LLC 5110 SAN FELIPE ST UNIT 304W, 5110 SAN FELIPE ST UNIT 304W, HOUSTON, TX 77056- 3623 1607 W. HOWARD LLC C/O CREATIVE DESIGNS, 4355 N RAVENSWOOD AVE, CHICAGO, IL 60613 1611 STERLING L L C 325 N WELLS ST SUITE 1000, CHICAGO, IL 60610 16TH & HOMAN BUILDING ACCOUNT 1559 S HOMAN AVE, CHICAGO, IL 60623 18TH STREET. DEVELOPMENT. CORP. 1839 S CARPENTER ST, CHICAGO, IL 60608-3347 201 N. WELLS INVESTORS, LLC. 505 N LAKE SHORE DR STE 214, CHICAGO, IL 60611 21ST & CALUMET 1 LLC. 3611 S NORMAL AVE, CHICAGO, IL 60609 2335 CHICAGO BUILDING, CCC PO BOX 8030, WILMETTE, IL 60091-8030 2507 N. -

2 History of Chicago

KATEDRA ANGLISTIKY A AMERIKANISTIKY FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI THE EMIGRATION OF CZECHS TO THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Kateřina Entlerová Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Jiří Flajšar, Ph.D. Olomouc 2012 Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně a uvedla v ní předepsaným způsobem všechnu použitou literaturu. V Olomouci dne ………………… Podpis ………………… I would like to express my thanks to my supervisor, Mgr. Jiří Flajšar, Ph.D. for all his help, valuable advice and useful suggestions given while writing this bachelor thesis. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 1 2 CHICAGO ................................................................................................................................... 3 2.1 Chicago Historical Timeline .................................................................................................... 3 2.2 Population ................................................................................................................................ 8 2.3 Etymology ................................................................................................................................ 9 2.4 Chicago aka Windy City .......................................................................................................... 9 3 HISTORY OF THE CZECH EMIGRATION TO THE UNITED STATES ...................... 11 3.1 Beginning of the Emigration until WWI ..............................................................................