An Ethnographic Study of Indigenous Contributions to the City of Duluth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dibaginjigaadeg Anishinaabe Ezhitwaad: a Tribal Climate Adaptation Menu

ginjigaadeg iba An D ish in a a b e E z h A i t w T r C a i a a b r d i n a g l f o C r l th i os m e wh a o t te ake A care of us da u ptation Men Abstract Climate change has impacted and will continue to impact indigenous peoples, their lifeways and culture, and the natural world upon which they rely, in unpredictable and potentially devastating ways. Many climate adaptation planning tools fail to address the unique needs, values and cultures of indigenous communities. This Tribal Climate Adaptation Menu, which was developed by a diverse group of collaborators representing tribal, academic, intertribal and government entities in Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan, provides a framework to integrate indigenous and traditional knowledge, culture, language and history into the climate adaptation planning process. Developed as part of the Climate Change Response Framework, the Tribal Climate Adaptation Menu is designed to work with the Northern Institute of Applied Climate Science (NIACS) Adaptation Workbook, and as a stand-alone resource. The Menu is an extensive collection of climate change adaptation actions for natural resource management, organized into tiers of general and more specific ideas. It also includes a companion Guiding Principles document, which describes detailed considerations for working with tribal communities. While this first version of the Menu was created based on Ojibwe and Menominee perspectives, languages, concepts and values, it was intentionally designed to be adaptable to other indigenous communities, allowing for the incorporation of their language, knowledge and culture. -

A Cooperative Model for Negotiating Treaty Rights in Minnesota Steven B

Law & Inequality: A Journal of Theory and Practice Volume 9 | Issue 3 Article 12 1991 Self-Determination and Reconciliation: A Cooperative Model for Negotiating Treaty Rights in Minnesota Steven B. Nyquist Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.umn.edu/lawineq Recommended Citation Steven B. Nyquist, Self-Determination and Reconciliation: A Cooperative Model for Negotiating Treaty Rights in Minnesota, 9 Law & Ineq. 533 (1991). Available at: http://scholarship.law.umn.edu/lawineq/vol9/iss3/12 Law & Inequality: A Journal of Theory and Practice is published by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Self-Determination and Reconciliation: A Cooperative Model for Negotiating Treaty Rights in Minnesota Steven B. Nyquist* Introduction [We] are willing to let you have [the] lands, but [we] wish to reserve the privilege of making sugar from the trees and get- ting [our] living from the Lakes and Rivers, as [we] have done heretofore .... It is hard to give up the lands. They will re- main, and cannot be destroyed .... You know we cannot live deprived of our lakes and rivers; there is some game on the lands yet; and for that reason also we wish to remain upon them, to get a living. The Great Spirit above, made the Earth, and causes it to produce, which enables us to live. 1 Aish-ke-bo-gi-ko-she (Flatmouth, Ojibwe Chief, Pillager Band, speaking on behalf of the Chiefs at the July 29, 1837 Treaty with the Chippewa2 Conference). Federal Native American policy has been markedly inconsis- tent,3 but throughout, treaties have remained the nucleus of the * B.S. -

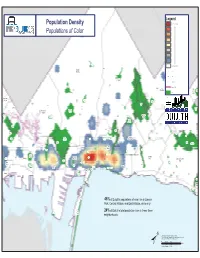

Population Density Populations of Color

Legend Legend Population Density Highest Population Density Populations of Color Sonside Park Lowest Population Density Duluth Heights School Æc Library Kenwood Hospital or Clinic Recreational Trail Rice Lake Park Woodland Athletic Lake Complex Park Annex Pleasant View Park Bayview Duluth Heights Community Heights Recreation Cntr Hartley Field Hartley Park Downer Park Janette Cody Pennel Park Pollay Arlington Park Piedmont Athletic Complex Morley Heights Hts/Parkview Oneota Park Piedmont Hunters Community Recreation Center Park Bagley Nature Area (UMD) Brewer Park Chester Park Bellevue Park Amity Park Amity Creek Park Enger Chester Quarry Municipal Copeland Lakeview Park Community Grant Community Park Golf Course Center Recreation Center Park-UMD Enger Hawk Park Ridge Hawk Ridge Nature Reserve Hilltop Park East Hillside Lincoln Congdon Park Old Park Main Cascade Park Park Portland Wheeler Square Athletic Washington Congdon Complex Central Com Rec Memorial Ctr Community Recreation Center Denfeld Hillside Park Lakeside-Lester Central Park Park Russell Midtown Civic Square Spirit Park Center Point of Rocks Park Valley Wade Sports Point of Complex Rocks Park Manchester Lincoln Square Lake Place Plaza Endion Leif Erickson Rose Garden Park Corner of Park the Lake CBD Park Lakewalk Washington East Square Irving Bayfront Park Oneota Grosvenor Square Lester/Amity Park Canal Park North Shore University Park Kitchi Gammi Park Franklin Park 46% of Duluth's populations of color live in Lincoln Park, Central Hillside, and East Hillside, while only Park 24% of Duluth's total population lives in these three Rice's Point Boat Landing Point neighborhoods. Data Source: Minnesota Population Center. National Historical Geographic Information System: Version 2.0 ± Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota 2011. -

Ecological Regions of Minnesota: Level III and IV Maps and Descriptions Denis White March 2020

Ecological Regions of Minnesota: Level III and IV maps and descriptions Denis White March 2020 (Image NOAA, Landsat, Copernicus; Presentation Google Earth) A contribution to the corpus of materials created by James Omernik and colleagues on the Ecological Regions of the United States, North America, and South America The page size for this document is 9 inches horizontal by 12 inches vertical. Table of Contents Content Page 1. Introduction 1 2. Geographic patterns in Minnesota 1 Geographic location and notable features 1 Climate 1 Elevation and topographic form, and physiography 2 Geology 2 Soils 3 Presettlement vegetation 3 Land use and land cover 4 Lakes, rivers, and watersheds; water quality 4 Flora and fauna 4 3. Methods of geographic regionalization 5 4. Development of Level IV ecoregions 6 5. Descriptions of Level III and Level IV ecoregions 7 46. Northern Glaciated Plains 8 46e. Tewaukon/BigStone Stagnation Moraine 8 46k. Prairie Coteau 8 46l. Prairie Coteau Escarpment 8 46m. Big Sioux Basin 8 46o. Minnesota River Prairie 9 47. Western Corn Belt Plains 9 47a. Loess Prairies 9 47b. Des Moines Lobe 9 47c. Eastern Iowa and Minnesota Drift Plains 9 47g. Lower St. Croix and Vermillion Valleys 10 48. Lake Agassiz Plain 10 48a. Glacial Lake Agassiz Basin 10 48b. Beach Ridges and Sand Deltas 10 48d. Lake Agassiz Plains 10 49. Northern Minnesota Wetlands 11 49a. Peatlands 11 49b. Forested Lake Plains 11 50. Northern Lakes and Forests 11 50a. Lake Superior Clay Plain 12 50b. Minnesota/Wisconsin Upland Till Plain 12 50m. Mesabi Range 12 50n. Boundary Lakes and Hills 12 50o. -

St. Louis County Heritage & Arts Center

St. Louis County Heritage & Arts Center Investing in the Duluth Depot Location: 506 W. Michigan Street, Duluth, MN 55802 11/27/18 Depot Commitment St. Louis County is demonstrating a recommitment to preserving and promoting the region’s history, arts and culture at the Depot. Overview— Depot Significance and History Depot Subcommittee Formation & Work Tenant Outreach Proposed Model Next Steps & Desired Outcomes 2 State-Wide & Regional Significance of Depot Represents a collaborative effort between the citizens of St. Louis County and county government to form a regional cultural and arts center out of an abandoned railroad depot Is on the National Register of Historic Places Has been identified as a potential Northern Lights Express (NLX) station Houses one of the oldest historical societies in the state—known for its extensive Native American and manuscript collections Has a notable collection of historic iron horses (trains/engines), including: o William Crooks—Minnesota’s first steam locomotive (during Civil War era) o 1870 Minnetonka—worked the historic transcontinental line o Giant Missabe Road Mallet 227—one of the world’s largest and most powerful steam locomotives o Northern Pacific Rotary Snowplow No. 2—constructed in 1887, making it the oldest plow of its type in existence (a Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark) Viewed as a stimulant to area tourism—a hub of history, culture and arts 3 Depot History 1892: Duluth Union Depot 1977-1985: Served Amtrak’s built—serving 7 rail lines, Arrowhead (Minneapolis-Duluth) and accommodating 5,000 passengers North Star (Chicago-Duluth) lines 2017: St. Louis County and 50+ trains per day requests $5.75M for 1999: Veterans’ Memorial critical repairs 1971: Depot placed on the National Hall established Register of Historic Places 1900 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 1973: Re-opened as the St. -

Newark Earthworks Center - Ohio State University and World Heritage - Ohio Executive Committee INDIANS and EARTHWORKS THROUGH the AGES “We Are All Related”

Welcoming the Tribes Back to Their Ancestral Lands Marti L. Chaatsmith, Comanche/Choctaw Newark Earthworks Center - Ohio State University and World Heritage - Ohio Executive Committee INDIANS AND EARTHWORKS THROUGH THE AGES “We are all related” Mann 2009 “We are all related” Earthen architecture and mound building was evident throughout the eastern third of North America for millennia. Everyone who lived in the woodlands prior to Removal knew about earthworks, if they weren’t building them. The beautiful, enormous, geometric precision of the Hopewell earthworks were the culmination of the combined brilliance of cultures in the Eastern Woodlands across time and distance. Has this traditional indigenous knowledge persisted in the cultural traditions of contemporary American Indian cultures today? Mann 2009 Each dot represents Indigenous architecture and cultural sites, most built before 1491 Miamisburg Mound is the largest conical burial mound in the USA, built on top of a 100’ bluff, it had a circumference of 830’ People of the Adena Culture built it between 2,800 and 1,800 years ago. 6 Miamisburg, Ohio (Montgomery County) Picture: Copyright: Tom Law, Pangea-Productions. http://pangea-productions.net/ Items found in mounds and trade networks active 2,000 years ago. years 2,000 active networks trade and indicate vast travel Courtesy of CERHAS, Ancient Ohio Trail Inside the 50-acre Octagon at Sunrise 8 11/1/2018 Octagon Earthworks, Newark, OH Indigenous people planned, designed and built the Newark Earthworks (ca. 2000 BCE) to cover an area of 4 square miles (survey map created by Whittlesey, Squier, and Davis, 1837-47) Photo Courtesy of Dan Campbell 10 11/1/2018 Two professors recover tribal knowledge 2,000 years ago, Indigenous people developed specialized knowledge to construct the Octagon Earthworks to observe the complete moon cycle: 8 alignments over a period of 18 years and 219 days (18.6 years) “Geometry and Astronomy in Prehistoric Ohio” Ray Hively and Robert Horn, 1982 Archaeoastronomy (Supplement to Vol. -

2001 Truck Route Study

Duluth-Superior Area Study $ # $ $$ $ # # # # # # # # â 1 â3 $ # 15 $ # $ # $ $ â # $ # 16 # $ $ â $ #$ $ # 7 $ $ # # $$ 14 $ â $ # $ $ $ # $ # $ â # $#$# # $ # $$ ## # #$ 8 # # # # â# # # # # #$# # # # # # $# ## #$$ # $$# # $ # # ### 9 #### # # # # ## # # # â #$$ #$#$ # # # ## $$ #### $ $$## $ #$$## $ $ #$ ## #$$ ##$$#$# ## $$$ $ ### $ $$$ ## #$# $ # ### $ ## $$# # # $$#$## # # $$ $# $ $ $ # ######## $# #$# $ #13 # 5 ## #######$####$# # # $$ # $ $ 6 #$###$#####$$## #$ # # # #â#### â ## ##$ $###11# $ â # $$ # ## ### ## $# # ##$ â# $ # 4 # ####### # # # ## #####$########## # # # ###### ## ######## ## â # ## # # 2 $ # # # $# # # # ### ## # # # â # ##### # # ### # # $ $ # $ $## $# # # # $ $ # $ # # # # # ## $ $ ## $# # $ # # 12# # $ # # â # # $ â10 Duluth-Superior Metropolitan Interstate Committee Approved April 18, 2001 Duluth-Superior Truck Route Study Approved April 18, 2001 Prepared by the Duluth-Superior Metropolitan Interstate Committee Duluth Superior urban area communities cooperating in planning and development through a joint venture of the Arrowhead Regional Development Commission and the Northwest Regional Planning Commission This study was funded through the Duluth-Superior Metropolitan Interstate Committee with funding from the: Federal Highway Administration Minnesota Department of Transportation Wisconsin Department of Transportation Arrowhead Regional Development Commission Northwest Regional Planning Commission Copies of the study are available from the Duluth-Superior Metropolitan Interstate Committee 221 West 1st Street, -

The Mythologizing of the Great Lakes Whaleback

VERNACULAR IN CURVES: THE MYTHOLOGIZING OF THE GREAT LAKES WHALEBACK by Joseph Thaddeus Lengieza April, 2016 Director of Thesis: Dr. Bradley Rodgers Major Department: Maritime Studies, History The “whaleback” type of bulk commodity freighter, indigenous to the Great Lakes of North America at the end of the nineteenth century, has engendered much notice for its novel appearance; however, this appearance masks the essential vernacularity of the vessel. Comparative disposition analysis reveals that whalebacks experienced longevity comparable to contemporary Great Lakes freighter of similar construction material and size, implying that popular narrative overstates whaleback abnormality. Market and social forces which contributed to the rise and fall of the whaleback type are explored. VERNACULAR IN CURVES: THE MYTHOLOGIZING OF THE GREAT LAKES WHALEBACK A Thesis Presented To the Faculty of the Department of Maritime Studies East Carolina University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Maritime Studies by Joseph Thaddeus Lengieza April, 2016 © Joseph Thaddeus Lengieza, 2016 VERNACULAR IN CURVES: THE MYTHOLOGIZING OF THE GREAT LAKES WHALEBACK By Joseph Thaddeus Lengieza APPROVED BY: DIRECTOR OF THESIS:_________________________________________________________ Bradley Rodgers, Ph.D. COMMITTEE MEMBER: _______________________________________________________ Nathan Richards, Ph.D. COMMITTEE MEMBER: _______________________________________________________ David Stewart, Ph.D. COMMITTEE MEMBER: _______________________________________________________ -

And the Florida State University Seminoles?): the Rt Ademark Registration Decision and Alternative Remedies Jack Achiezer Guggenheim [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Florida State University College of Law Florida State University Law Review Volume 27 | Issue 1 Article 10 1999 Renaming the Redskins (and the Florida State University Seminoles?): The rT ademark Registration Decision and Alternative Remedies Jack Achiezer Guggenheim [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jack A. Guggenheim, Renaming the Redskins (and the Florida State University Seminoles?): The Trademark Registration Decision and Alternative Remedies, 27 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 287 (1999) . http://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol27/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW RENAMING THE REDSKINS (AND THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SEMINOLES?): THE TRADEMARK REGISTRATION DECISION AND ALTERNATIVE REMEDIES Jack Achiezer Guggenheim VOLUME 27 FALL 1999 NUMBER 1 Recommended citation: Jack Achiezer Guggenheim, Renaming the Redskins (and the Florida State University Seminoles?): The Trademark Registration Decision and Alternative Remedies, 27 FLA. ST. U. L. REV. 287 (1999). RENAMING THE REDSKINS (AND THE FLORIDA STATE SEMINOLES?): THE TRADEMARK REGISTRATION DECISION AND ALTERNATIVE REMEDIES JACK ACHIEZER GUGGENHEIM* I. INTRODUCTION..............................................................................................................287 -

The Law, Courts and Lawyers in the Frontier Days of Minnesota: an Informal Legal History of the Years 1835 to 1865 Robert J

William Mitchell Law Review Volume 2 | Issue 1 Article 1 1976 The Law, Courts and Lawyers in the Frontier Days of Minnesota: An Informal Legal History of the Years 1835 to 1865 Robert J. Sheran Timothy J. Baland Follow this and additional works at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr Recommended Citation Sheran, Robert J. and Baland, Timothy J. (1976) "The Law, Courts and Lawyers in the Frontier Days of Minnesota: An Informal Legal History of the Years 1835 to 1865," William Mitchell Law Review: Vol. 2: Iss. 1, Article 1. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr/vol2/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in William Mitchell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law Sheran and Baland: The Law, Courts and Lawyers in the Frontier Days of Minnesota: An THE LAW, COURTS, AND LAWYERS IN THE FRONTIER DAYS OF MINNESOTA: AN INFORMAL LEGAL HISTORY OF THE YEARS 1835 TO 1865* By ROBERT J. SHERANt Chief Justice, Minnesota Supreme Court and Timothy J. Balandtt In this article Chief Justice Sheran and Mr. Baland trace the early history of the legal system in Minnesota. The formative years of the Minnesota court system and the individuals and events which shaped them are discussed with an eye towards the lasting contributionswhich they made to the system of today in this, our Bicentennialyear. -

Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate

Fordham University DigitalResearch@Fordham Faculty Publications Jewish Studies 2020 Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate Fordham University Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/jewish_facultypubs Part of the History Commons, and the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Fordham University, "Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate" (2020). Faculty Publications. 2. https://fordham.bepress.com/jewish_facultypubs/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Jewish Studies at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Media Technology & The Dissemination of Hate November 15th, 2019-May 31st 2020 O’Hare Special Collections Fordham University & Center for Jewish Studies Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate Highlights from the Fordham Collection November 15th, 2019-May 31st, 2020 Curated by Sally Brander FCRH ‘20 Clare McCabe FCRH ‘20 Magda Teter, The Shvidler Chair in Judaic Studies with contributions from Students from the class HIST 4308 Antisemitism in the Fall of 2018 and 2019 O’Hare Special Collections Walsh Family Library, Fordham University Table of Contents Preface i Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate 1 Christian (Mis)Interpretation and (Mis)Representation of Judaism 5 The Printing Press and The Cautionary Tale of One Image 13 New Technology and New Opportunities 22 -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation

NPS Form 10-900-b 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Jan. 1987) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service WAV 141990' National Register of Historic Places NATIONAL Multiple Property Documentation Form REGISTER This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Cobscook Area Coastal Prehistoric Sites_________________________ B. Associated Historic Contexts ' • The Ceramic Period; . -: .'.'. •'• •'- ;'.-/>.?'y^-^:^::^ .='________________________ Suscruehanna Tradition _________________________ C. Geographical Data See continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in j£6 CFR Part 8Q^rjd th$-§ecretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. ^"-*^^^ ~^~ I Signature"W"e5rtifying official Maine Historic Preservation O ssion State or Federal agency and bureau I, hereby, certify that this