Special Collector's Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trace and Minor Element Analysis of Obsidian From

r r TRACE AND MINOR ELEMENT ANALYSIS OF OBSIDIAN r FROM THE SAN FRANCISCO VOLCANIC FIELD r USING X-RAY FLUORESCENCE r r [ r A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty F' ! 1. Northern Arizona University r ~ l rL In Partial Fulfillment r of the Requirements for the Degree r Master of Science r ' r r \. by r Suzanne C. Sanders L April 1981 _[r r t f l I. r l l t I ABSTRACT . r l f ! f r I Obsidian from eight locations in the San Franciscan volcanic field in northern Arizona were analyzed for 20 minor and trace elements r using x-ray fluorescence analysis. The intensity ratios relative to iron were statistically analyzed r and the trace and minor element patterns established. The obsidian rL outcrops clustered into four well defined groups consisting of two localities apiece: Government Mountain/Obsidian Tank, Slate Mountain/ r Kendrick Peak, Robinson Crater/O'Leary Peak, and RS Hill/Spring Valley. r Each of the four distinct groups was treated individually to refine the separation between the similar sites. Classification function coeffi r cients were calculated for each locality, then these were used to identify the source of thirteen obsidian artifacts recovered from a Northern r Arizona archaeological site. r r r r r r r r l r ..r r r r I CONTENTS r t Page LIST OF TABLES .. iii r LIST OF FIGURES . v r Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION . 1 r, 2. SAMPLE COLLECTION 7 3. METHODS AND MATERIALS 12 r 4. ANALYSIS OF THE DATA .. 17 r 5. -

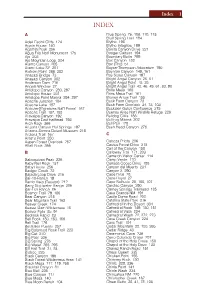

Index 1 INDEX

Index 1 INDEX A Blue Spring 76, 106, 110, 115 Bluff Spring Trail 184 Adeii Eechii Cliffs 124 Blythe 198 Agate House 140 Blythe Intaglios 199 Agathla Peak 256 Bonita Canyon Drive 221 Agua Fria Nat'l Monument 175 Booger Canyon 194 Ajo 203 Boundary Butte 299 Ajo Mountain Loop 204 Box Canyon 132 Alamo Canyon 205 Box (The) 51 Alamo Lake SP 201 Boyce-Thompson Arboretum 190 Alstrom Point 266, 302 Boynton Canyon 149, 161 Anasazi Bridge 73 Boy Scout Canyon 197 Anasazi Canyon 302 Bright Angel Canyon 25, 51 Anderson Dam 216 Bright Angel Point 15, 25 Angels Window 27 Bright Angel Trail 42, 46, 49, 61, 80, 90 Antelope Canyon 280, 297 Brins Mesa 160 Antelope House 231 Brins Mesa Trail 161 Antelope Point Marina 294, 297 Broken Arrow Trail 155 Apache Junction 184 Buck Farm Canyon 73 Apache Lake 187 Buck Farm Overlook 34, 73, 103 Apache-Sitgreaves Nat'l Forest 167 Buckskin Gulch Confluence 275 Apache Trail 187, 188 Buenos Aires Nat'l Wildlife Refuge 226 Aravaipa Canyon 192 Bulldog Cliffs 186 Aravaipa East trailhead 193 Bullfrog Marina 302 Arch Rock 366 Bull Pen 170 Arizona Canyon Hot Springs 197 Bush Head Canyon 278 Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum 216 Arizona Trail 167 C Artist's Point 250 Aspen Forest Overlook 257 Cabeza Prieta 206 Atlatl Rock 366 Cactus Forest Drive 218 Call of the Canyon 158 B Calloway Trail 171, 203 Cameron Visitor Center 114 Baboquivari Peak 226 Camp Verde 170 Baby Bell Rock 157 Canada Goose Drive 198 Baby Rocks 256 Canyon del Muerto 231 Badger Creek 72 Canyon X 290 Bajada Loop Drive 216 Cape Final 28 Bar-10-Ranch 19 Cape Royal 27 Barrio -

Sell-1536, Field Trip Notes, , MILS

CONTACT INFORMATION Mining Records Curator Arizona Geological Survey 416 W. Congress St., Suite 100 Tucson, Arizona 85701 520-770-3500 http://www.azgs.az.gov [email protected] The following file is part of the James Doyle Sell Mining Collection ACCESS STATEMENT These digitized collections are accessible for purposes of education and research. We have indicated what we know about copyright and rights of privacy, publicity, or trademark. Due to the nature of archival collections, we are not always able to identify this information. We are eager to hear from any rights owners, so that we may obtain accurate information. Upon request, we will remove material from public view while we address a rights issue. CONSTRAINTS STATEMENT The Arizona Geological Survey does not claim to control all rights for all materials in its collection. These rights include, but are not limited to: copyright, privacy rights, and cultural protection rights. The User hereby assumes all responsibility for obtaining any rights to use the material in excess of “fair use.” The Survey makes no intellectual property claims to the products created by individual authors in the manuscript collections, except when the author deeded those rights to the Survey or when those authors were employed by the State of Arizona and created intellectual products as a function of their official duties. The Survey does maintain property rights to the physical and digital representations of the works. QUALITY STATEMENT The Arizona Geological Survey is not responsible for the accuracy of the records, information, or opinions that may be contained in the files. The Survey collects, catalogs, and archives data on mineral properties regardless of its views of the veracity or accuracy of those data. -

Ironwood Forest National Monument Resources Summary

Natural Resources Summary (5/2017) Ironwood Forest National Monument Geology & Cultural History of Ironwood Forest National Monument-IFNM, Southern Arizona ____________________________________ INFM Parameters • Established 9 June 2000 - Exe. Order President W.J. Clinton • Land Mangement: Bureau of Land Management • Footprint: 188,619 acres (includes 59,922 acres non-federal lands, chiefly State Trust lands, and minor private holdings) • Cultural features: 200+ Hohokam sites; historical mine-related sites • Current Uses: Recreation, cattle grazing, mining on pre-existing mine sites • Threatened Species: Ferruginous pygmy owl, desert bighorn sheep, lesser long-nosed bat, turk’s head cactus Physiographic Features Basin & Range Province, Roskruge Mtns., Samaniego Hills, Sawtooth Mtns., Silver Bell Mtns., Sonoran Desert, Western Silver Bell Mtns. Mining History • Predominantly in the Silver Bell Mtns. • Major Ore Deposit(s) type: porphyry copper • Ore: copper, lead, zinc, molybdenum, gold Map of the Ironwood Forest National Monument (BLM). The IFNM surrounds and partially encompasses the Silver Bell metallic mineral district and either covers parts of or encompasses the Waterman, Magonigal and the Roskruge mineral districts. The most productive area has been the Silver Bell Mining District, where active mining continues to this day, immediately southwest of the monument, and by grandfather clause, on the the monument proper. The Silver Bell Mmining District evolved from a collection of intermittent, poorly financed and managed underground mining operations in the late 1800s to mid-1900s struggling to make a profit from high grade ores; to a small but profitable producer, deploying innovative mining practices and advancements in technology to Mineral Districts of eastern Pima County. Yellow highlighted successfully develop the district’s large, low-grade copper resource districts are incorporated in part or entirely in IFNM (AZGS (D. -

Summits on the Air – ARM for the USA (W7A

Summits on the Air – ARM for the U.S.A (W7A - Arizona) Summits on the Air U.S.A. (W7A - Arizona) Association Reference Manual Document Reference S53.1 Issue number 5.0 Date of issue 31-October 2020 Participation start date 01-Aug 2010 Authorized Date: 31-October 2020 Association Manager Pete Scola, WA7JTM Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Document S53.1 Page 1 of 15 Summits on the Air – ARM for the U.S.A (W7A - Arizona) TABLE OF CONTENTS CHANGE CONTROL....................................................................................................................................... 3 DISCLAIMER................................................................................................................................................. 4 1 ASSOCIATION REFERENCE DATA ........................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Program Derivation ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 General Information ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Final Ascent -

1. WEB SITE RESEARCH Topic Research: Grand Canyon Travel

1. WEB SITE RESEARCH Topic research: Grand Canyon Travel Guide 1. What is the educational benefit of the information related to your topic? Viewers will learn about places to visit and things to do at Grand Canyon National Park. 2. What types of viewers will be interested in your topic? Visitors from U.S. and around the world who plan to visit Grand Canyon 3. What perceived value will your topic give to your viewers? The idea on how to get to the Grand Canyon and what kinds of activities that they can have at the Grand Canyon. 4. Primary person(s) of significance in the filed of your topic? The Grand Canyon National Park is the primary focus of my topic. 5. Primary person(s) that made your topic information available? The information was providing by the National Park Service, Wikitravel and Library of the Congress. 6. Important moments or accomplishments in the history of your topic? In 1919, The Grand Canyon became a national park in order to give the best protection and to preserve all of its features. 7. How did the media of times of your topic treat your topic? On February 26, 1919, President Woodrow Wilson signed into law a bill establishing the Grand Canyon as one of the nation's national parks. 8. Current events related to your topic? Italian Developers want to build big resort, shopping mall, and housing complex near Grand Canyon. They started buying land near South Rim of the Grand Canyon and building a project. 9. ListServ discussion and social media coverage of your topic? Grand Canyon Hikers group in Yahoo Group and Rafting Grand Canyon Group. -

The Geology of the El Tiro Hills, West Silver Bell Mountains, Pima County, Arizona

The geology of the El Tiro Hills, West Silver Bell Mountains, Pima County, Arizona Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic); maps Authors Clarke, Craig Winslow, 1938- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 02/10/2021 09:29:50 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/551863 THE GEOLOGY OF THE EL TIRO HILLS, WEST SILVER BELL MOUNTAINS, PIMA COUNTY, ARIZONA by Craig W. Clarke A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1966 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of require ments for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is de posited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholar ship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. -

INDEX of MINING PROPERTIES in PIMA COUNTY, ARIZONA Bureau

Index of Mining Properties in Pima County, Arizona Authors Keith, S.B. Citation Keith, S.B., Index of Mining Properties in Pima County, Arizona. Arizona Bureau of Geology and Mineral Technology Bulletin 189, 161 p. Rights Arizona Geological Survey. All rights reserved. Download date 11/10/2021 11:59:34 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/629555 INDEX OF MINING PROPERTIES IN PIMA COUNTY, ARIZONA by Stanton B. Keith Geologist Bulletin 189 1974 Reprinted 1984 Arizona Bureau of Geology and Mineral Technology Geological Survey Branch The University of Arizona Tucson ARIZONA BUREAU Of GEOLOGY AND MINERAL TECHNOLOGY The Arizona Bureau of Geology and Mineral Technology was established in 1977 by an act of the State Legislature. Under this act, the Arizona Bureau of Mines, created in 1915, was renamed and reorganized and its mission was redefined and expanded. The Bureau of Geology and Mineral Technology, a Division of the University of Arizona administered by the Arizona Board of Regents, is charged by the Legislature to conduct research and provide information about the geologic setting of the State, including its mineral and energy resources, its natural attributes, and its natural hazards and limitations. In order to carry out these functions, the Bureau is organized into two branches: Geological Survey Branch. Staff members conduct research, do geologic mapping, collect data, and provide information about the geologic setting of the State to: a) assist in developing an understanding of the geologic factors that influ ence the locations of metallic, non-metallic, and mineral fuel resources in Arizona, and b) assist in developing an understanding of the geologic materials and pro cesses that control or limit human activities in the state. -

San Francisco Mountains Forest Heserve, Arizona

Professional Paper No. 22 Series H, Forestry, 7 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES D. WALCOTT, DIRECTOR \ FOREST CONDITIONS lN 'fHE- SAN FRANCISCO MOUNTAINS FOREST HESERVE, ARIZONA BY JOHN B. LEIBERG, THEODORE F. RIXON, AND ARTHUR DODWELL WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY F. G. PLUMMER ·wASHINGTON G 0 Y E R N 1\I E N T I' HI N T IN G 0 ];' F I C E 1904 CONT .. ENTS. Page.. Letter of transmittaL_. __._._. ____-_._._._ .. _._ .. _.. _. ______ . __ _._._._- __._. ________ ._· __________ .~ __ . ____ . __ .___ 9 Introdnetion.·.-_-_. ______________ ._._._._._._._. ___ .. _______ .___ -_._. __ . ___________ . ____ . _. _________ ---- _ ___ 11 Boundaries·. ___ .----- ___ .·.·-·-·-·-·-·-·-_._. __ . __________ ._ .. _.._._. ______ . _______________ . _____ .___ 11 Surface features ___ . _ _- ..·: ______ ._._._ ..·.- ___ .· _ _. _ _. __ . _ _. ___________ .: ___________ . ________ ._______ 13 Soil·. _. _: _. _.. __ _. .. _ . _. __ .. __. .· ..· .... _. _. _..: ____ _. __. __ _. .· __.. __ . ___ .. __ . __ . __ . __ .. _____ . ___ .. 15 Drainage_._. _ _. ___ . _____________________ . __________ _.:. _ _. ________ . ____ . ___ ------_________ 15 Forest and womllan<.l .· __ . __ . __ . __ . __ . _____ ·- : _.. ·_____ . ___________ . ____ .· __ . _____ . _....... _ _ 17 Zones or types of arborescent growth_ . _.·. _. __.: _. __ . _: __. ... ____ . _______ . __ . __ . _.. _.. ___ . _ 18 Aspect and character of timber belts ____ . -

Grand Canyon National Park

To Bryce Canyon National Park, KANAB To St. George, Utah To Hurricane, Cedar City, Cedar Breaks National Monument, To Page, Arizona To Kanab, Utah and St. George, Utah V and Zion National Park Gulch E 89 in r ucksk ive R B 3700 ft R M Lake Powell UTAH 1128 m HILDALE UTAH I L ARIZONA S F COLORADO I ARIZONA F O gin I CITY GLEN CANYON ir L N V C NATIONAL 89 E 4750 ft N C 1448 m RECREATION AREA A L Glen Canyon C FREDONIA I I KAIBAB INDIAN P Dam R F a R F ri U S a PAGE RESERVATION H 15 R i ve ALT r 89 S 98 N PIPE SPRING 3116 ft I NATIONAL Grand Canyon National Park 950 m 389 boundary extends to the A MONUMENT mouth of the Paria River Lees Ferry T N PARIA PLATEAU To Las Vegas, Nevada U O Navajo Bridge M MARBLE CANYON r e N v I UINKARET i S G R F R I PLATEAU F I 89 V E R o V M L I L d I C a O r S o N l F o 7921ft C F 2415 m K I ANTELOPE R L CH JACOB LAKE GUL A C VALLEY ALT P N 89 Camping is summer only E L O K A Y N A S N N A O C I O 89T T H A C HOUSE ROCK N E L E N B N VALLEY YO O R AN C A KAIBAB NATIONAL Y P M U N P M U A 89 J L O C FOREST O K K D O a S U N Grand Canyon National Park- n F T Navajo Nation Reservation boundary F a A I b C 67 follows the east rim of the canyon L A R N C C Y r O G e N e N E YO k AN N C A Road to North Rim and all TH C OU Poverty Knoll I services closed in winter. -

Presidential Documents 37259 Presidential Documents

Federal Register / Vol. 65, No. 114 / Tuesday, June 13, 2000 / Presidential Documents 37259 Presidential Documents Proclamation 7320 of June 9, 2000 Establishment of the Ironwood Forest National Monument By the President of the United States of America A Proclamation The landscape of the Ironwood Forest National Monument is swathed with the rich, drought-adapted vegetation of the Sonoran Desert. The monument contains objects of scientific interest throughout its desert environment. Stands of ironwood, palo verde, and saguaro blanket the monument floor beneath the rugged mountain ranges, including the Silver Bell Mountains. Ragged Top Mountain is a biological and geological crown jewel amid the depositional plains in the monument. The monument presents a quintessential view of the Sonoran Desert with ancient legume and cactus forests. The geologic and topographic variability of the monument contributes to the area's high biological diversity. Ironwoods, which can live in excess of 800 years, generate a chain of influences on associated understory plants, affecting their dispersal, germina- tion, establishment, and rates of growth. Ironwood is the dominant nurse plant in this region, and the Silver Bell Mountains support the highest density of ironwood trees recorded in the Sonoran Desert. Ironwood trees provide, among other things, roosting sites for hawks and owls, forage for desert bighorn sheep, protection for saguaro against freezing, burrows for tortoises, flowers for native bees, dense canopy for nesting of white-winged doves and other birds, and protection against sunburn for night blooming cereus. The ironwood-bursage habitat in the Silver Bell Mountains is associated with more than 674 species, including 64 mammalian and 57 bird species. -

Basemap – Dot Exercise

ak k Pe 419 ric nd Kendrick Park Ke 773 546 760 Kendrick Park 6005 Wildlife 545B O'Leary Peak 418 W h i te Ho rs e H ills O'Leary 418 Lookout 418 193 erffer H Bear Hochd ills Jaw 9124N Sunset Crater 180 552 552 National Monument Abineau 151 Lava's Edge 9140K Nordic Village Waterline Lava Sunset Crater Bismarck Flow Lake Lockett 420 Meadow Lenox Crater Rees Aubineau Peak Peak Fern 244 Mtn Humphreys 794 H Peak 244A a 245 r 9141U t P 776 r a i r i e Humphreys Cinder Lake Inner Basin Regional 9004K Aspen Nature Doyle Peak Brandis Agassiz Peak C 9004L Waterline 9125G i n d e r Trails L Fremont a k Peak e 9008L s 420 Fernwood M a Timberline n a 244B g e Schultz m Peak e n t A r e Weatherford a Deer SUCCESS Veit Kachina 6064D Hill Spring 9123Q 151 Arizona 522 222 244 Secret 743 222B GT 9122P Newham 420 556B Secret Rocky 556 222A Moto Old Caves Sunset 511A Little Little Bear Elden Arizona Little Elden Mtn Wing Mtn 511 171 222 Moto Fort 164B Valley Schultz ills 519 Creek e H Brookbank ak 89 y L Dr Doney Park 557 9121Q Upper Sandy Oldham Heart Seep Chimney 180 Flue Christmas Rocky Tree Ridge Fatmans Loop 668D Elden Oldham Mt Elden Lookout Bellemont Tom Moody T 518 Picture u r Canyon k e A-1 Mtn Preserve y Don H il Weaver ls 510B Pipeline Buffalo Cosnino Park 40 Arizona Observatory Mesa Winona 518 515 506 Thorpe Observatory Park Sunnyside Mesa Continental Navajo Army Natural Area Depot Anasazi 40 Downtown Campbell Mesa Sinagua Walnut Meadows 745 Arizona Little America Recreational trails 764 FUTS trails NAU 40 Arizona on ny C a lnut Street Walnut Canyon Wa Dry Lake Loop National Rim Monument 82 Highway/major road Island Charles O.