Volume 17 1990 Issue 49

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Peace Fails in Guinea Bissau? a Political Economy Analysis of the ECOWAS-Brokered Conakry Accord

d Secur n ity a e S c e a r i e e s P FES SENEGAL GUINEA-BISSAU NORTH ATLANTIC OCEAN GUINEA Habibu Yaya Bappah Why Peace Fails in Guinea Bissau? A Political Economy Analysis of the ECOWAS-brokered Conakry Accord SENEGAL GUINEA-BISSAU NORTH ATLANTIC OCEAN GUINEA Habibu Yaya Bappah Why Peace Fails in Guinea Bissau? A Political Economy Analysis of the ECOWAS-brokered Conakry Accord About the author Dr Habibu Yaya Bappah is a full time Lecturer in the Department of Political Science/International Studies at Ahmadu Bello University Zaria, Nigeria. His teaching and research interests are in regional integration, regional security and governance, human rights, democracy and development with a particular focus on the African Union and ECOWAS. He has had stints and research fellowships in the Department of Political Affairs, Peace and Security at the ECOWAS Commission and in the African Union Peace & Security Programme at the Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia. He is an alumnus of the African Leadership Centre (ALC) at King’s College London. Imprint Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Peace and Security Centre of Competence Sub-Saharan Africa Point E, boulevard de l’Est, Villa n°30 P.O. Box 15416 Dakar-Fann, Senegal Tel.: +221 33 859 20 02 Fax: +221 33 864 49 31 Email: [email protected] www.fes-pscc.org ©Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung 2017 Layout : Green Eyez Design SARL, www.greeneyezdesign.com ISBN : 978-2-490093-01-4 “Commercial use of all media published by the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) is not permitted without the written consent of the FES. -

Guinea-Bissau: Second Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper

© 2011 International Monetary Fund December 2011 IMF Country Report No. 11/353 June 31, 2011 January 29, 2001 January 29, 2001 January 29, 2001 January 29, 2001 Guinea-Bissau: Second Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper This poverty reduction strategy paper on Guinea-Bissau was prepared in broad consultation with stakeholders and development partners, including the staffs of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. The PRSP describes the country’s macroeconomic, structural, and social policies in support of growth and poverty reduction, as well as associated external financing needs and major sources of financing. This country document is being made available on the IMF website, together with the Joint Staff Advisory Note on the Second Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper, by agreement with the member country as a service to users of the IMF website. Copies of this report are available to the public from International Monetary Fund Publication Services 700 19th Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20431 Telephone: (202) 623-7430 Telefax: (202) 623-7201 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.imf.org International Monetary Fund Washington, D.C. REPUBLIC OF GUINEA-BISSAU MINISTRY OF ECONOMY, PLANNING, AND REGIONAL INTEGRATION SECOND NATIONAL POVERTY REDUCTION STRATEGY PAPER DENARP/PRSP II (2011–2015) Bissau, June 2011 CONTENTS Acronyms and Abbreviations ............................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................. -

Appraisal Report Kankan-Kouremale-Bamako Road Multinational Guinea-Mali

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FUND ZZZ/PTTR/2000/01 Language: English Original: French APPRAISAL REPORT KANKAN-KOUREMALE-BAMAKO ROAD MULTINATIONAL GUINEA-MALI COUNTRY DEPARTMENT OCDW WEST REGION JANUARY 1999 SCCD : N.G. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PROJECT INFORMATION BRIEF, EQUIVALENTS, ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS, LIST OF ANNEXES AND TABLES, BASIC DATA, PROJECT LOGICAL FRAMEWORK, ANALYTICAL SUMMARY i-ix 1 INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Project Genesis and Background.................................................................................... 1 1.2 Performance of Similar Projects..................................................................................... 2 2 THE TRANSPORT SECTOR ........................................................................................... 3 2.1 The Transport Sector in the Two Countries ................................................................... 3 2.2 Transport Policy, Planning and Coordination ................................................................ 4 2.3 Transport Sector Constraints.......................................................................................... 4 3 THE ROAD SUB-SECTOR .............................................................................................. 5 3.1 The Road Network ......................................................................................................... 5 3.2 The Automobile Fleet and Traffic................................................................................. -

Saharan Africa

T.C. SAKARYA UNIVERSITY MIDDLE EAST INSTITUTE THE DETERMINANTS, MOTIVES, AND SOCIO- CULTURAL IMPACTS OFARAB-AID TO SUB- SAHARAN AFRICA. MASTER’S THESIS Mohamed CAMARA Department : Middle East Studies Thesis Supervisor: Assist. Prof. Philipp O. AMOUR JULY – 2018 DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is written in accordance with the scientific code of ethics and that, this work is original and where the works of others used has been duly acknowledged. There is no falsification of used data and that no part of this thesis is presented for study at this university or any other university. Mohamed CAMARA 02.07.2018 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT My tremendous gratitude goes to my late father for his support and guidance in enabling me further my studies to this level. I also thank the teaching and administrative staff of the Middle East Institute in Sakarya University. A heartfelt appreciation goes to the Republic of Turkey for the good learning environment and the hospitality that was offered to me during my studies. I am most grateful to my supervisor Assist. Prof. Dr. Philipp O. Amour for his research assistance and patience to review this project. In his capacity as my research guide, I have benefitted not only from his Academic advices but also advices that has taught me the principles of ethics and discipline in research. I am alone liable for possible mistakes. Special thanks to Aboubacar Sidiki Amara Sylla, Malang Bojang, Hashiru Mohamed and Elif Kaya for their unwavering moral and technical supports. Finally, I am highly indebted to my family and best friends, especially my uncle for his financial support throughout my Academic life. -

Republic of Guinea: Overcoming Growth Stagnation to Reduce Poverty

Report No. 123649-GN Public Disclosure Authorized REPUBLIC OF GUINEA OVERCOMING GROWTH STAGNATION TO REDUCE POVERTY Public Disclosure Authorized SYSTEMATIC COUNTRY DIAGNOSTIC March 16, 2018 International Development Association Country Department AFCF2 Public Disclosure Authorized Africa Region International Finance Corporation Sub-Saharan Africa Department Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency Sub-Saharan Africa Department Public Disclosure Authorized WORLD BANK GROUP IBRD IFC Regional Vice President: Makhtar Diop : Vice President: Dimitris Tsitsiragos Country Director: Soukeyna Kane Director: Vera Songwe : Country Manager: Rachidi Radji Country Manager: Cassandra Colbert Task Manager: Ali Zafar : Resident Representative: Olivier Buyoya Co-Task Manager: Yele Batana ii LIST OF ACRONYMS AGCP Guinean Central Procurement Agency ANASA Agence Nationale des Statistiques Agricoles (National Agricultural Statistics Agency) Agence de Promotion des Investissements et des Grands Travaux (National Agency for APIX Promotion of Investment and Major Works) BCRG Banque Centrale de la République de Guinée (Central Bank of Guinea) CEQ Commitment to Equity CGE Computable General Equilibrium Conseil National pour la Démocratie et le Développement (National Council for CNDD Democracy and Development) Confédération Nationale des Travailleurs de Guinée (National Confederation of CNTG Workers of Guinea) CPF Country Partnership Framework CPIA Country Policy and Institutional Assessment CRG Crédit Rural de Guinée (Rural Credit of Guinea) CWE China Water and -

English) Relative to Those That TVET Trainees Are Developing During Their Courses

Escaping the Low-Growth Trap Public Disclosure Authorized Guinea-Bissau Country Economic Memorandum Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Macroeconomics, Trade and Investment Global Practice Public Disclosure Authorized AFCF1 Country Management Unit Africa Region 1 Report No: AUS0001916 © 2020 The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org Some rights reserved This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this work is subject to copyright. Because The World Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for no ncommercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. Attribution—Please cite the work as follows: World Bank. (July 2020). Guinea-Bissau Country Economic Memorandum. © World Bank. All queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to World Bank Publications, The World Bank Group, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax: 202-522-2625; e-mail: [email protected]. 2 Acknowledgments The Country Economic Memorandum was prepared by a team led by Fiseha Haile (TTL and Economist, EA2M1). -

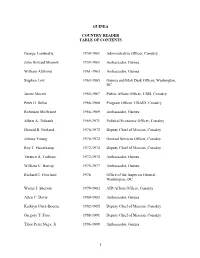

Table of Contents

GUINEA COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS George Lambrakis 1959-1961 Administrative Officer, Conakry John Howard Morrow 1959-1961 Ambassador, Guinea William Attwood 1961-1963 Ambassador, Guinea Stephen Low 1963-1965 Guinea and Mali Desk Officer, Washington, DC James Moceri 1965-1967 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Conakry Peter O. Sellar 1966-1968 Program Officer, USAID, Conakry Robinson McIlvaine 1966-1969 Ambassador, Guinea Albert A. Thibault 1969-1971 Political/Economic Officer, Conakry Donald R. Norland 1970-1972 Deputy Chief of Mission, Conakry Johnny Young 1970-1972 General Services Officer, Conakry Roy T. Haverkamp 1972-1974 Deputy Chief of Mission, Conakry Terence A. Todman 1972-1975 Ambassador, Guinea William C. Harrop 1975-1977 Ambassador, Guinea Richard C. Howland 1978 Office of the Inspector General, Washington, DC Walter J. Sherwin 1979-1982 AID Affairs Officer, Conakry Allen C. Davis 1980-1983 Ambassador, Guinea Kathryn Clark-Bourne 1982-1985 Deputy Chief of Mission, Conakry Gregory T. Frost 1988-1991 Deputy Chief of Mission, Conakry Tibor Peter Nagy, Jr. 1996-1999 Ambassador, Guinea 1 Joyce E. Leader 1999-2000 Ambassador, Guinea GEORGE LAMBRAKIS Administrative Officer Conakry (1959-1961) George Lambrakis was born in Illinois in 1931. After receiving his bachelor’s degree from Princeton University in 1952, he went on to earn his master’s degree from Johns Hopkins University in 1953 and his law degree from Tufts University in 1969. His career has included positions in Saigon, Pakse, Conakry, Munich, Tel Aviv, and Teheran. Mr. Lambrakis was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy in June 2002. LAMBRAKIS: Bill Lewis was my immediate boss. And after two years in INR I was given my choice of three African assignments, I chose Conakry because it was a brand new post, and I spoke French. -

2005-2009-Guinea-Country Strategy Paper

AFRICAN DEVELOPPEMENT BANK AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FUND REPUBLIC OF GUINEA RESULTS-BASED COUNTRY STRATEGY PAPER 2005-2009 COUNTRY OPERATIONS DEPARTMENT (WEST REGION) July 2005 Table of Contents CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS ................................................................................................................................................................................................................i FISCAL YEAR...........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................i ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................................................................................................................................i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................ii I. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................................................................................................................1 II. COUNTRY CONTEXT ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................2 -

Urban-Bias and the Roots of Political Instability

Urban-bias and the Roots of Political Instablity: The case for the strategic importance of the rural periphery in sub-Saharan Africa By Beth Sharon Rabinowitz A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Steven K. Vogel, Chair Professor Michael Watts Professor Robert Price Professor Catherine Boone Fall 2013 COPYRIGHT Abstract Urban-bias and the Roots of Political Instablity: The case for the strategic importance of the rural periphery in sub-Saharan Africa By Beth Sharon Rabinowitz Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Steven K. Vogel, Chair Urban-bias and the Roots of Political Instability: the case for the strategic importance of the rural periphery in sub-Saharan Africa seeks to unravel a conundrum in African politics. Since the 1980s, we have witnessed two contradictory trends: on the one hand, coups, which have become rare events world-wide, have continued to proliferate in the region; concurrently, several African countries – such as Ghana, Uganda, Burkina Faso and Benin – have managed to escape from seemingly insurmountable coup-traps. What explains this divergence? To address these contradictory trends, I focus initially on Ghana and Cote d‟Ivoire, neighboring states, with comparable populations, topographies, and economies that have experienced contrasting trajectories. While Ghana suffered five consecutive coups from the 1966 to 1981, Cote d‟Ivoire was an oasis of stability and prosperity. However, by the end of the 20th century, Ghana had emerged as one of the few stable two-party democracies on the continent, as Cote d‟Ivoire slid into civil war. -

The Mineral Industry of Guinea in 1998

THE MINERAL INDUSTRY OF GUINEA By Philip M. Mobbs Guinea was the world’s second largest bauxite producer and Alcan Aluminium Ltd. of Canada, Aluminium Pechiney of had the world’s largest bauxite resources (Plunkert, 1999). France, and Alcoa Inc. of the United States. In 1998, to Mining accounted for about 16% of the nation’s estimated $3.6 debottleneck production, CBG began rehabilitation and billion gross domestic product and about 80% of the value of upgrade of the bauxite conveyor system in Kamsar from the rail Guinea’s exports (U.S. Department of State, September 1998, terminal to the processing plant. Background notes, accessed November 13, 1999, at URL The state-owned Société des Bauxites de Kindia (SBK) http://www.eti-bull.net/USEMBASSY/notes.html; World Bank, proposed to restore its production to the operation’s original 3- September 22, 1999, Guinea at a glance, accessed November Mt/yr capacity. SBK’s production, about one-half of capacity, 10, 1999, at URL http://www.worldbank.org/data/ was exported to Ukraine. countrydata/countrydata.html).1 The limited domestic demand The dispute between the owners of the Société d’Economie for crude minerals resulted in the mineral sector effectively Mixte Friguia continued into 1998. Friguia, owned by the dominating the nation’s exports. Less than 10% of mined Frialco Holding Co. (51%) and the Government (49%), bauxite was used to produce alumina in Guinea. In 1998, the operated the Fria bauxite mine and the Kimbo alumina country’s total exports were valued at $843 million compared refinery. The year began with the Frialco partners (Alcan, with $797 million in 1997 (World Bank, September 22, 1999, 20%; Aluminium Pechiney, 30%; Hydro Aluminium a.s. -

POTENTIAL IMPACTS of the AFRICAN CONTINENTAL FREE TRADE AREA (AFCFTA) on SELECTED OIC COUNTRIES Case of Cote D’Ivoire, Egypt, Guinea, Mozambique, Tunisia and Uganda

TECHNICAL REPORT POTENTIAL IMPACTS OF THE AFRICAN CONTINENTAL FREE TRADE AREA (AFCFTA) ON SELECTED OIC COUNTRIES Case of Cote d’Ivoire, Egypt, Guinea, Mozambique, Tunisia and Uganda Prepared by About ITFC The International Islamic Trade Finance Corporation (ITFC) is a member of the Islamic Contents Development Bank (IsDB) Group. It was established with the primary objective of advancing trade among OIC member countries, which would ultimately contribute to the overarching ACRONYMS 4 goal of improving the socioeconomic conditions of the people across the world. Commencing operations in January 2008, ITFC has provided more than US$51 billion of financing to OIC LIST OF FIGURES 5 member countries, making it the leading provider of trade solutions for these member LIST OF TABLES 5 countries’ needs. With a mission to become a catalyst for trade development for OIC member countries and beyond, the Corporation helps entities in member countries gain better access FOREWORD 6 to trade finance and provides them with the necessary trade-related capacity-building tools, which would enable them to successfully compete in the global market. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 8 About SESRIC 1. Introduction 10 2. Current Trade Patterns and Tariff Barriers 14 The Statistical, Economic and Social Research and Training Centre for Islamic Countries to Trade (SESRIC), a subsidiary organ of the Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC), is operating in Ankara, Turkey since June 1978 as the main economic research arm, statistics centre 3. Model and Estimation 22 and training organ of the OIC. The Centre has been engaged with statistical data collection, 4. Output and Welfare Effects 26 collation and dissemination on and for the OIC member countries, undertaking the preparation of research papers, reports and studies on economic cooperation and development issues 5. -

We Recommend Not to Cite This First Draft IMPACTS of the DOHA ROUND and ECOWAS on the GUINEA-BISSAU ECONOMY

We recommend not to cite this first draft IMPACTS OF THE DOHA ROUND AND ECOWAS ON THE GUINEA-BISSAU ECONOMY: AN ANALYSIS WITH CGE MODEL Júlio Vicente Cateia1 Dr. Terciane Sabadini de Carvalho2 Dr. Maurício Vaz Lobo Bittencourt3 Abstract: Trade in agricultural products is very sensitive to shocks in world markets. However, just a few decades ago agricultural commodities had their trade regulated, which occurred only in the beginning of the early 2000s, marking the first steps of developing and less developed countries towards the liberalization of their products. This study aims to analyze the proposal of tariff reduction formalized in the Doha agreement on the economy of Guinea-Bissau, contributing to the analysis of trade liberalization and its implications for development, particularly discussing the effects on poverty and welfare. The analysis was conducted by Guinea-Bissau economy-based computable general equilibrium model calibrated with the 2007 data. Large negative short-term impacts in welfare and poverty were attributed to a partial cut in import tariffs (56%). As the effects on the product that the model was able to capture bring an expansion in the cash crops sectors (mainly millet, sorghum, maize and rice) and in some industries and services sectors, the tariff reduction policy could promote the diversification of national production. Keywords: Trade agreements. Computable General Equilibrium Model. Guinea- Bissau JEL code: C68; F14; Q17 1. Introduction Guinea-Bissau is a country with small economy fundamentally based on agricultural production, which accounts for more than 60% of its gross domestic product (GDP) and 90% of its exports. Considering the total of 68% of the population over 15 years employed, 61% corresponds to employment in the agricultural sector, 5.8% industrial employment and 34.1% employment in the services sector (ILO, 2017).