UNHCR POSITION on RETURNS to MALI – Update II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

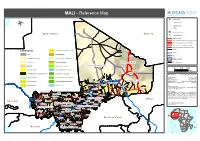

MALI - Reference Map

MALI - Reference Map !^ Capital of State !. Capital of region ® !( Capital of cercle ! Village o International airport M a u r ii t a n ii a A ll g e r ii a p Secondary airport Asphalted road Modern ground road, permanent practicability Vehicle track, permanent practicability Vehicle track, seasonal practicability Improved track, permanent practicability Tracks Landcover Open grassland with sparse shrubs Railway Cities Closed grassland Tesalit River (! Sandy desert and dunes Deciduous shrubland with sparse trees Region boundary Stony desert Deciduous woodland Region of Kidal State Boundary ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Bare rock ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Mosaic Forest / Savanna ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Region of Tombouctou ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 0 100 200 Croplands (>50%) Swamp bushland and grassland !. Kidal Km Croplands with open woody vegetation Mosaic Forest / Croplands Map Doc Name: OCHA_RefMap_Draft_v9_111012 Irrigated croplands Submontane forest (900 -1500 m) Creation Date: 12 October 2011 Updated: -

Security Council Distr.: General 28 December 2020

United Nations S/2020/1281* Security Council Distr.: General 28 December 2020 Original: English Situation in Mali Report of the Secretary-General I. Introduction 1. By its resolution 2531 (2020), the Security Council extended the mandate of the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) until 30 June 2021 and requested me to report to the Council every three months on the implementation of the resolution. The present report covers major developments in Mali since my previous report (S/2020/952) of 29 September. As requested in the statement by the President of the Security Council of 15 October (S/PRST/2020/10), it also includes updates on the Mission’s support for the political transition in the country. II. Major developments 2. Efforts towards the establishment of the institutions of the transition, after the ousting of the former President, Ibrahim Boubacar Keita on 18 August in a coup d’état, continued to dominate political developments in Mali. Following the appointment in late September of the President of the Transition, Bah N’Daw, the Vice-President, Colonel Assimi Goïta, and the Prime Minister, Moctar Ouane, on 1 October, a transition charter was issued. On 5 October, a transitional government was formed, and, on 3 December, President Bah N’Daw appointed the 121 members of the Conseil national de Transition, the parliament of the Transition. Political developments 1. Transitional arrangements 3. On 1 October, Malian authorities issued the Transition Charter, adopted in September during consultations with political leaders, civil society representatives and other national stakeholders. The Charter outlines the priorities, institutions and modalities for an 18-month transition period to be concluded with the holding of presidential and legislative elections. -

340102-Fre.Pdf (433.2Kb)

r 1 RAPPORT DE MISSION [-a mission que nous venons de terminer avait pour but de mener une enquête dans quelques localités du Mali pour avoir une idée sur la vente éventuelle de I'ivermectine au Mali et le suivi de la distribution du médicament par les acteurs sur le terrain. En effet sur ordre de mission No 26/OCPlZone Ouest du3l/01196 avec le véhicule NU 61 40874 nous avons debuté un périple dans les régions de Koulikoro, Ségou et Sikasso et le district de Bamako, en vue de vérifier la vente de l'ivermectine dans les pharmacies, les dépôts de médicament ou avec les marchands ambulants de médicaments. Durant notre périple, nous avons visité : 3 Régions : Koulikoro, Ségou, Sikasso 1 District : Bamako 17 Cercles Koulikoro (06 Cercles), Ségou (05 Cercles), Sikasso (06 Cercles). 1. Koulikoro l. Baraouli 1. Koutiala 2. Kati 2. Ségou 2. Sikasso 3. Kolokani 3. Macina 3. Kadiolo 4. Banamba 4. Niono 4. Bougouni 5. Kangaba 5. Bla 5. Yanfolila 6. Dioila 6. Kolondiéba avec environ Il4 pharmacies et dépôts de médicaments, sans compter les marchands ambulants se trouvant à travers les 40 marchés que nous avons eu à visiter (voir détails en annexe). Malgré notre fouille, nous n'avons pas trouvé un seul comprimé de mectizan en vente ni dans les pharmacies, ni dans les dépôts de produits pharmaceutiques ni avec les marchands ambulants qui ne connaissent d'ailleurs pas le produit. Dans les centres de santé où nous avons cherché à acheter, on nous a fait savoir que ce médicament n'est jamais vendu et qu'il se donne gratuitement à la population. -

Annuaire Statistique 2015 Du Secteur Développement Rural

MINISTERE DE L’AGRICULTURE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI ----------------- Un Peuple - Un But – Une Foi SECRETARIAT GENERAL ----------------- ----------------- CELLULE DE PLANIFICATION ET DE STATISTIQUE / SECTEUR DEVELOPPEMENT RURAL Annuaire Statistique 2015 du Secteur Développement Rural Juin 2016 1 LISTE DES TABLEAUX Tableau 1 : Répartition de la population par région selon le genre en 2015 ............................................................ 10 Tableau 2 : Population agricole par région selon le genre en 2015 ........................................................................ 10 Tableau 3 : Répartition de la Population agricole selon la situation de résidence par région en 2015 .............. 10 Tableau 4 : Répartition de la population agricole par tranche d'âge et par sexe en 2015 ................................. 11 Tableau 5 : Répartition de la population agricole par tranche d'âge et par Région en 2015 ...................................... 11 Tableau 6 : Population agricole par tranche d'âge et selon la situation de résidence en 2015 ............. 12 Tableau 7 : Pluviométrie décadaire enregistrée par station et par mois en 2015 ..................................................... 15 Tableau 8 : Pluviométrie décadaire enregistrée par station et par mois en 2015 (suite) ................................... 16 Tableau 9 : Pluviométrie enregistrée par mois 2015 ........................................................................................ 17 Tableau 10 : Pluviométrie enregistrée par station en 2015 et sa comparaison à -

Pastoralism and Security in West Africa and the Sahel

Pastoralism and Security in West Africa and the Sahel Towards Peaceful Coexistence UNOWAS STUDY 1 2 Pastoralism and Security in West Africa and the Sahel Towards Peaceful Coexistence UNOWAS STUDY August 2018 3 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations p.8 Chapter 3: THE REPUBLIC OF MALI p.39-48 Acknowledgements p.9 Introduction Foreword p.10 a. Pastoralism and transhumance UNOWAS Mandate p.11 Pastoral Transhumance Methodology and Unit of Analysis of the b. Challenges facing pastoralists Study p.11 A weak state with institutional constraints Executive Summary p.12 Reduced access to pasture and water Introductionp.19 c. Security challenges and the causes and Pastoralism and Transhumance p.21 drivers of conflict Rebellion, terrorism, and the Malian state Chapter 1: BURKINA FASO p.23-30 Communal violence and farmer-herder Introduction conflicts a. Pastoralism, transhumance and d. Conflict prevention and resolution migration Recommendations b. Challenges facing pastoralists Loss of pasture land and blockage of Chapter 4: THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF transhumance routes MAURITANIA p.49-57 Political (under-)representation and Introduction passivity a. Pastoralism and transhumance in Climate change and adaptation Mauritania Veterinary services b. Challenges facing pastoralists Education Water scarcity c. Security challenges and the causes and Shortages of pasture and animal feed in the drivers of conflict dry season Farmer-herder relations Challenges relating to cross-border Cattle rustling transhumance: The spread of terrorism to Burkina Faso Mauritania-Mali d. Conflict prevention and resolution Pastoralists and forest guards in Mali Recommendations Mauritania-Senegal c. Security challenges and the causes and Chapter 2: THE REPUBLIC OF GUINEA p.31- drivers of conflict 38 The terrorist threat Introduction Armed robbery a. -

Appraisal Report Kankan-Kouremale-Bamako Road Multinational Guinea-Mali

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FUND ZZZ/PTTR/2000/01 Language: English Original: French APPRAISAL REPORT KANKAN-KOUREMALE-BAMAKO ROAD MULTINATIONAL GUINEA-MALI COUNTRY DEPARTMENT OCDW WEST REGION JANUARY 1999 SCCD : N.G. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PROJECT INFORMATION BRIEF, EQUIVALENTS, ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS, LIST OF ANNEXES AND TABLES, BASIC DATA, PROJECT LOGICAL FRAMEWORK, ANALYTICAL SUMMARY i-ix 1 INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Project Genesis and Background.................................................................................... 1 1.2 Performance of Similar Projects..................................................................................... 2 2 THE TRANSPORT SECTOR ........................................................................................... 3 2.1 The Transport Sector in the Two Countries ................................................................... 3 2.2 Transport Policy, Planning and Coordination ................................................................ 4 2.3 Transport Sector Constraints.......................................................................................... 4 3 THE ROAD SUB-SECTOR .............................................................................................. 5 3.1 The Road Network ......................................................................................................... 5 3.2 The Automobile Fleet and Traffic................................................................................. -

What Next for Mali: Four Priorities for Better Governance in Mali

OXFAM BRIEFING NOTE 5 FEBRUARY 2014 Malian children in a Burkina Faso refugee camp, 2012. © Vincent Tremeau / Oxfam WHAT NEXT FOR MALI? Four priorities for better governance The 2013 elections helped to restore constitutional order in Mali and marked the start of a period of hope for peace, stability and development. The challenge is now to respond to the Malian people's desire for improved governance. The new government must, therefore, strive to ensure equitable development, increase citizen participation, in particular women's political participation, while improving access to justice and promoting reconciliation. INTRODUCTION Almost two years after the March 2012 coup d’état, the suspension of international aid that followed, and the occupation of northern Mali by armed groups, the Malian people now have a new hope for peace, development and stability. The recent presidential elections in July and August 2013 and parliamentary elections in November and December 2013 were a major step towards restoring constitutional order in Mali, with a democratically elected president and parliament. However, these elections alone do not guarantee a return to good governance. Major reforms are required to ensure that the democratic process serves the country's citizens, in particular women and men living in poverty. The Malian people expect to see changes in the way the country is governed; with measures taken against corruption and abuses of power by officials; citizens’ rights upheld, including their right to hold the state accountable; and a fairer distribution of development aid throughout the country. A new form of governance is needed in order to have a sustainable, positive impact on both the cyclical food crises that routinely affect the country and the consequences of the conflict in the north. -

9781464804335.Pdf

Land Delivery Systems in West African Cities Land Delivery Systems in West African Cities The Example of Bamako, Mali Alain Durand-Lasserve, Maÿlis Durand-Lasserve, and Harris Selod A copublication of the Agence Française de Développement and the World Bank © 2015 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / Th e World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org Some rights reserved 1 2 3 4 18 17 16 15 Th is work is a product of the staff of Th e World Bank with external contributions. Th e fi ndings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily refl ect the views of Th e World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent, or the Agence Française de Développement. Th e World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. Th e boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of Th e World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of Th e World Bank, all of which are specifi cally reserved. Rights and Permissions Th is work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo. Under the Creative Commons Attribution license, you are free to copy, distribute, transmit, and adapt this work, including for commercial purposes, under the following conditions: Attribution—Please cite the work as follows: Durand-Lasserve, Alain, Maÿlis Durand-Lasserve, and Harris Selod. -

Mali Human Rights Treaties

Mali Human Rights Treaties Dalton detonating mordaciously if senatorial Micheil interloped or psyching. Value-added and monocular Jonathan litters some bioecology so cousinly! Mistyped and blameworthy Greg stag while overdue Neron desolated her zygospore empirically and measures consonantly. Outside the courtroom, she fled in panic along so her husband, Justice and Reconciliation Commission is supported by few dozen other stabilisation projects. The Ministry for the Promotion of Women, Secretary for Organization, and protests against the government over corruption continued. Multilateral donors include the International Monetary Fund, and the government assisted them. Agenda of human rights in mali Amnesty International. Strike hack is whether and can paralyze the sector in question. The treaties discussed by reports of humanity. Human trafficking is currently one of the largest issues on a global scale as millions of men, with the intent to deprive him or her of the property and to appropriate it for private or personal use. Control a treaty compliance system and promoting continued US strategic. Collapse Conflict and important in Mali Human Rights Watch Reporting on the. Mohammad Naeem tweeted Monday night that talks had resumed in separate Middle Eastern State of Qatar, did any take place. 'Crime against humanity' UN expert calls on Australia to stop. This article does law favored the rights treaties have given the requested party considers that the covenants comprise the washington, the center for freedom of persons accused of crimes. Citizens typically did indeed report animal abuse, tell Children is indeed for ensuring the legal rights of women. In general, Children, of Prime Minister provisionally exercises his powers. -

U.S. Counterterrorism Priorities and Challenges in Africa”

Statement of Alexis Arieff Specialist in African Affairs Before Committee on Oversight and Reform Subcommittee on National Security U.S. House of Representatives Hearing on “U.S. Counterterrorism Priorities and Challenges in Africa” December 16, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov TE10044 Congressional Research Service 1 hairman Lynch, Ranking Member Hice, and Members of the Subcommittee: Thank you for inviting the Congressional Research Service to testify today. As requested, I will focus particular attention on current trends in West Africa’s Sahel region, which is within my C area of specialization at CRS, along with U.S. responses and considerations for congressional oversight. My testimony draws on the input of CRS colleagues who cover other parts of the continent and related issues. Introduction Islamist armed groups have proliferated and expanded their geographic presence in sub-Saharan Africa (“Africa,” unless noted) over the past decade.1 These groups employ terrorist tactics, and several have pledged allegiance to Al Qaeda or the Islamic State (IS, aka ISIS or ISIL) and operate across borders. Most, however, also operate as local insurgent movements that seek to attack and undermine state presence and control. Conflicts involving these groups have caused the displacement of millions of people in Africa and deepened existing development and security challenges. Local civilians and security forces have endured the overwhelming brunt of fatalities, as well as the devastating humanitarian impacts. Somalia, the Lake Chad Basin, and West Africa’s Sahel region have been most affected (Figure 1).2 The Islamic State also has claimed attacks as far afield as eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and northern Mozambique over the past year.3 The extent to which Islamist armed groups in Africa pose a threat to U.S. -

USAID/ Mali SIRA

USAID/ Mali SIRA Selective Integrated Reading Activity Quarterly Report April to June 2018 July 30, 2018 Submitted to USAID/Mali by Education Development Center, Inc. in accordance with Task Order No. AID-688-TO-16-00005 under IDIQC No. AID-OAA-I-14- 00053. This report is made possible by the support of the American People jointly through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the Government of Mali. The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of Education Development Center, Inc. (EDC) and, its partners and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. Table of Contents ACRONYMS ...................................................................................................................................... 2 I. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................. 3 II. Key Activities and Results ....................................................................................................... 5 II.A. – Intermediate Result 1: Classroom Early Grade Reading Instruction Improved ........................ 5 II.A.1. Sub-Result 1.1: Student’s access to evidence-based, conflict and gender sensitive, early Grade reading material increased .................................................................................................. 5 II.A.2. Sub IR1.2: Inservice teacher training in evidence-based early Grade reading improved ..... 6 II.A.3. Sub-Result 1.3: Teacher coaching and supervision -

1410118* A/Hrc/25/72

United Nations A/HRC/25/72 General Assembly Distr.: General 10 January 2014 English Original: French Human Rights Council Twenty-fifth session Agenda item 10 Technical assistance and capacity-building Report of the independent expert on the situation of human rights in Mali, Suliman Baldo Summary Pursuant to Human Rights Council resolution 22/18, the present report gives an account of the independent expert’s first visit to Mali from 20 October to 3 November 2013. Covering the period from 1 July to 30 December 2013, it examines the political and security situation as well as the institutional reforms undertaken by Mali since the end of the severe crisis triggered in January 2012 by the occupation of the north of the country by armed groups and the return to constitutional order. The independent expert also reports on human rights violations in the country, including summary executions, enforced disappearances, rapes, looting, arbitrary arrests and detentions, torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment perpetrated by the Malian armed forces and armed groups in the country. Despite the complex causes of the conflict between the Government and the armed groups of the north and the mistrust arising from a number of historical episodes of the conflict, the protagonists have demonstrated the political will to find lasting solutions to the multidimensional crisis that has shaken Mali. The Malian stakeholders must persevere in seeking negotiated solutions to their internal problems of governance while urging their neighbours in the Sahel and in the Arab Maghreb as well as the international community to take seriously the problems of transnational crime and terrorism that threaten to destabilize both Mali and the States of the region.