How Family Law Fails in a New Era of Class Division

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long Adele Rolling in the Deep Al Green

AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long Adele Rolling in the Deep Al Green Let's Stay Together Alabama Dixieland Delight Alan Jackson It's Five O'Clock Somewhere Alex Claire Too Close Alice in Chains No Excuses America Lonely People Sister Golden Hair American Authors The Best Day of My Life Avicii Hey Brother Bad Company Feel Like Making Love Can't Get Enough of Your Love Bastille Pompeii Ben Harper Steal My Kisses Bill Withers Ain't No Sunshine Lean on Me Billy Joel You May Be Right Don't Ask Me Why Just the Way You Are Only the Good Die Young Still Rock and Roll to Me Captain Jack Blake Shelton Boys 'Round Here God Gave Me You Bob Dylan Tangled Up in Blue The Man in Me To Make You Feel My Love You Belong to Me Knocking on Heaven's Door Don't Think Twice Bob Marley and the Wailers One Love Three Little Birds Bob Seger Old Time Rock & Roll Night Moves Turn the Page Bobby Darin Beyond the Sea Bon Jovi Dead or Alive Living on a Prayer You Give Love a Bad Name Brad Paisley She's Everything Bruce Springsteen Glory Days Bruno Mars Locked Out of Heaven Marry You Treasure Bryan Adams Summer of '69 Cat Stevens Wild World If You Want to Sing Out CCR Bad Moon Rising Down on the Corner Have You Ever Seen the Rain Looking Out My Backdoor Midnight Special Cee Lo Green Forget You Charlie Pride Kiss an Angel Good Morning Cheap Trick I Want You to Want Me Christina Perri A Thousand Years Counting Crows Mr. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Felice Bryant and Country Music Songwriting in the 1950S

Bridgewater Review Volume 39 Issue 1 Article 4 4-2020 Felice Bryant and Country Music Songwriting in the 1950s Paula Bishop Bridgewater State University Follow this and additional works at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/br_rev Part of the Composition Commons Recommended Citation Bishop, Paula (2020). Felice Bryant and Country Music Songwriting in the 1950s. Bridgewater Review, 39(1), 4-7. Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/br_rev/vol39/iss1/4 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Felice Bryant and Country Music Songwriting in the 1950s Paula Bishop f you were a country music artist working in Nashville in the 1950s, you might have found Iyourself at the home of Nashville songwriters, Felice and Boudleaux Bryant, enjoying one of Felice’s home-cooked meals. Boudleaux would present songs that he and Felice had written while Felice offered suggestions and corrections from the kitchen. On the surface this domestic scene suggests conventional gender roles in which the husband handles business Nashville image (Photo Credit: NiKreative / while the wife entertains the guests, but in fact, the Alamy Stock Photo) Bryants had learned to capitalize on Felice’s culinary the country music industry of the 1950s skills and outgoing personality in order to build their and build a successful career, becom- professional songwriting career. As she once quipped, ing what Mary Bufwack and Robert Oermann called the “woman who if they fed the artists a “belly full of spaghetti and ears ignited the explosion of women writers full of songs,” they were more likely to choose a song on music Row.” written by the Bryants. -

BEAR FAMILY RECORDS TEL +49(0)4748 - 82 16 16 • FAX +49(0)4748 - 82 16 20 • E-MAIL [email protected]

BEAR FAMILY RECORDS TEL +49(0)4748 - 82 16 16 • FAX +49(0)4748 - 82 16 20 • E-MAIL [email protected] ARTIST The Everly Brothers TITLE Rock LABEL Bear Family Productions CATALOG # BCD 17321 PRICE-CODE AR EAN-CODE ÇxDTRBAMy173219z ISBN-CODE 978-3-89916-693-4 FORMAT 1 CD digipac with 36-page booklet GENRE Rock ’n’ Roll TRACKS 30 PLAYING TIME 65:36 G The chart-topping duo's biggest and best hits, alongside one-of-a-kind rarities G Includes the million-sellers Bye Bye Love, Wake Up, Little Susie, Bird Dog, Cathy's Clown, When Will I Be Loved, all in stunning remastered sound! G Features lesser-heard B-sides, several of which – such as Be Bop A-Lula and Should We Tell Him – also made the US charts. G Atotal of 30 songs covering 1957-62 plus a lavish booklet comprising many previously unseen photos, a detailed biography and discography! INFORMATION In a recording career which began in 1955 and spanned five decades, brothers Don and Phil Everly registered 38 Top 100 chart entries in the U.S. alone between 1957 and 1984. In the U.K., they had 30 hits from 1957 to 1984, toured extensively, and were hugely popular in Germany, Holland, Australia and the Philippines throughout the 1950s, 60s & 70s. This compilation gathers together all of the Everly Brothers’ biggest hits from the Rock 'n' Roll era including the international million-seller Cathy's Clown and Bye Bye Love,their debut single for the CADENCE label. The pre-eminent vocal duo of the rock era, their style inspired such artists as Simon & Garfunkel, Peter & Gordon and Chad & Jeremy to follow in their footsteps and straight into the charts. -

FOREVER EVERLY. Presented by Chatterbox Entertainment

FOREVER EVERLY. Presented By Chatterbox Entertainment. a COMPANY PROFILE.......................................................................................................................... 3 ABOUT THE SHOW........................................................................................................................... 3 PERFORMANCE SPECIFICS........................................................................................................... 4 AUDIENCE ENGAGEMENT............................................................................................................. 5 MARKETING........................................................................................................................................ 5 IMAGES…………………………………………………………………………………………………………..7 FEE STRUCTURE……………………………………………………………………………………………..8 PRODUCTION & TECHNICAL……………………………………………………………………………8 CONTACTS............................................................................................................................................ 9 Forever Everly. Page 3 PRESENTER INFORMATION Chatterbox Entertainment is a professional entertainment production company. Run by Sheila Lorraine who is an experienced performer herself as well as a sound and lighting technician. Sheila has produced many shows for venues all over the world. Chatterbox manages various shows and artistes and also runs a booking agency for other artistes including local, national and international acts. Chatterbox also produces one off variety shows and theme shows, and can -

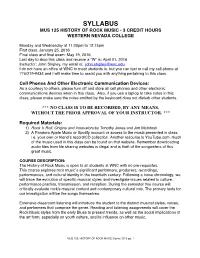

MUS 125 SYLLABUS(Spring 2016)

SYLLABUS MUS 125 HISTORY OF ROCK MUSIC - 3 CREDIT HOURS WESTERN NEVADA COLLEGE Monday and Wednesday at 11:00pm to 12:15pm First class: January 25, 2016 Final class and final exam: May 19, 2016 Last day to drop this class and receive a “W” is: April 01, 2016 Instructor: John Shipley, my email is: [email protected] I do not have an office at WNC to meet students in, but you can text or call my cell phone at 775/219-9434 and I will make time to assist you with anything pertaining to this class. Cell Phones And Other Electronic Communication Devices: As a courtesy to others, please turn off and store all cell phones and other electronic communications devices when in this class. Also, if you use a laptop to take notes in this class, please make sure the noise emitted by the keyboard does not disturb other students. *** NO CLASS IS TO BE RECORDED, BY ANY MEANS, WITHOUT THE PRIOR APPROVAL OF YOUR INSTRUCTOR. *** Required Materials: 1) Rock 'n Roll, Origins and Innovators by Timothy Jones and Jim McIntosh 2) A Pandora Apple Music or Spotify account or access to the music presented in class, i.e. your own or friend’s record/CD collection. Another resource is YouTube.com, much of the music used in this class can be found on that website. Remember downloading audio files from file sharing websites is illegal and is theft of the songwriters of this great music. COURSE DESCRIPTION: The History of Rock Music is open to all students at WNC with no pre-requisites. -

The Eddie Cochran Story

SHOW OF STARS 95 bassist Emory Gordy, who'd go on to play with or produce Emmylou Harris, Steve Earle, Roy Orbison, and George Jones; drummer Dennis St. John, who'd later work with Neil Diamond, Carole Bayer Sager, and the Band; and keyboardist Spooner Oldham, who'd played with Percy Sledge, Wilson Pickett, and Aretha Franklin and who'd later work with Neil Young, Bob Dylan, and Jackson Browne. Kindred was persistent. I recommended to them some great players; they'd decided that only I would do. Since they were already signed to Warner Brothers and had tremendous touring and recording potential, I decided to join them, recording a pair of Kindred albums in 1971 and 1972 and touring throughout America and Canada opening for Three Do,g Night. Through our shared management connection, I soon got a call from Jerry Edmonton, the drummer from Steppenwolf. They want ed me to join their band. I stayed for three albums and four years as the group's lead guitarist, one of its songwriters , and a co-lead and backing vocalist. Toward the end of my tenure with "the Wolf," I received a call from the Flying Burrito Brothers, the country-rock outfit founded by Gram Parsons and Chris Hillman of the Byrds. They needed a guitarist for a two -week tour. I went down to the rehearsal hall, jammed with the group, and found myself a Burrito for the next fourteen months. Like Uncle Ed in his brief lifetime, I have played with a plethora of artists-from obscure to superstars and try to take something of value away from every musical expe rience. -

EVERLYPEDIA (Formerly the Everly Brothers Index – TEBI) Coordinated by Robin Dunn & Chrissie Van Varik

EVERLYPEDIA (formerly The Everly Brothers Index – TEBI) Coordinated by Robin Dunn & Chrissie van Varik EVERLYPEDIA PART 2 E to J Contact us re any omissions, corrections, amendments and/or additional information at: [email protected] E______________________________________________ EARL MAY SEED COMPANY - see: MAY SEED COMPANY, EARL and also KMA EASTWOOD, CLINT – Born 31st May 1930. There is a huge quantity of information about Clint Eastwood his life and career on numerous websites, books etc. We focus mainly on his connection to The Everly Brothers and in particular to Phil Everly plus brief overview of his career. American film actor, director, producer, composer and politician. Eastwood first came to prominence as a supporting cast member in the TV series Rawhide (1959–1965). He rose to fame for playing the Man with No Name in Sergio Leone’s Dollars trilogy of spaghetti westerns (A Fistful of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More, and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly) during the 1960s, and as San Francisco Police Department Inspector Harry Callahan in the Dirty Harry films (Dirty Harry, Magnum Force, The Enforcer, Sudden Impact and The Dead Pool) during the 1970s and 1980s. These roles, along with several others in which he plays tough-talking no-nonsense police officers, have made him an enduring cultural icon of masculinity. Eastwood won Academy Awards for Best Director and Producer of the Best Picture, as well as receiving nominations for Best Actor, for his work in the films Unforgiven (1992) and Million Dollar Baby (2004). These films in particular, as well as others including Play Misty for Me (1971), The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976), Pale Rider (1985), In the Line of Fire (1993), The Bridges of Madison County (1995) and Gran Torino (2008), have all received commercial success and critical acclaim. -

Jukebox Oldies

JUKEBOX OLDIES – MOTOWN ANTHEMS Disc One - Title Artist Disc Two - Title Artist 01 Baby Love The Supremes 01 I Heard It Through the Grapevine Marvin Gaye 02 Dancing In The Street Martha Reeves & The Vandellas 02 Jimmy Mack Martha Reeves & The Vandellas 03 Reach Out, I’ll Be There Four Tops 03 You Keep Me Hangin’ On The Supremes 04 Uptight (Everything’s Alright) Stevie Wonder 04 The Onion Song Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell 05 Do You Love Me The Contours 05 Got To Be There Michael Jackson 06 Please Mr Postman The Marvelettes 06 What Becomes Of The Jimmy Ruffin 07 You Really Got A Hold On Me The Miracles 07 Reach Out And Touch Diana Ross 08 My Girl The Temptations 08 You’re All I Need To Get By Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell 09 Where Did Our Love Go The Supremes 09 Reflections Diana Ross & The Supremes 10 I Can’t Help Myself Four Tops 10 My Cherie Amour Stevie Wonder 11 The Tracks Of My Tears Smokey Robinson & The Miracles 11 There’s A Ghost In My House R. Dean Taylor 12 My Guy Mary Wells 12 Too Busy Thinking About My Marvin Gaye 13 (Love Is Like A) Heatwave Martha Reeves & The Vandellas 13 The Happening The Supremes 14 Needle In A Haystack The Velvelettes 14 It’s A Shame The Spinners 15 It’s The Same Old Song Four Tops 15 Ain’t No Mountain High Enough Diana Ross 16 Get Ready The Temptations 16 Ben Michael Jackson 17 Stop! (in the name of love) The Supremes 17 Someday We’ll Be Together Diana Ross & The Supremes 18 How Sweet It Is Marvin Gaye 18 Ain’t Too Proud To Beg The Temptations 19 Take Me In Your Arms Kim Weston 19 I’m Still Waiting Diana Ross 20 Nowhere To Run Martha Reeves & The Vandellas 20 I’ll Be There The Jackson 5 21 Shotgun Junior Walker & The All Stars 21 What’s Going On Marvin Gaye 22 It Takes Two Marvin Gaye & Kim Weston 22 For Once In My Life Stevie Wonder 23 This Old Heart Of Mine The Isley Brothers 23 Stoned Love The Supremes 24 You Can’t Hurry Love The Supremes 24 ABC The Jackson 5 25 (I’m a) Road Runner JR. -

From Everly Family to Cadence Discography – Feb.2016

CHRONOLOGY OF THE EVERLY BROTHERS RECORDINGS UP TO 1960 THIS COVERS THE PRE-COLUMBIA ERA, EARLY DEMO/AUDITION RECORDINGS, THE FOUR COLUMBIA TRACKS AND THE CADENCE SESSIONS. SHOWS RECORDING DATE (UK STYLE), MASTER NUMBER, INITIAL 45 SINGLE OR EP (WHICHEVER FIRST), FIRST VINYL LP & PRINCIPLE CD RELEASES. ALBUM TRACKS (FIRST TIME ONLY - REPEATS NOT SHOWN) HIGHLIGHTED IN COLOUR FOR IDENTIFICATION. HOWEVER DUE TO SOME CONFUSION & DUPLICATION WITH EARLY CADENCE ALBUMS TWO COLOURS ARE USED - FIRST OR MAIN COLOUR INDICATING THE PRIMARY RELEASE. THE VINYL RECORD NUMBERS ARE USA CADENCE UNLESS OTHERWISE STATED. DATE KEY TO INITIAL VINYL ABLUMS KEY TO PRIMARY (IN NO ORDER) CDs: 04 1958 THE EBs - "THEY'RE OFF AND ROLLING…" - CLP 3003 1. THE EBs - "THEY'RE OFF AND ROLLING…" RHINO R2 70211 *1 12 1958 SONGS OUR DADDY TAUGHT US - CLP 3016 *1 as CLP 3003 but with 'ten o'clock' 'Poor Jenny' 03 1959 THE EBs BEST - CLP 3025 2. SONGS OUR DADDY TAUGHT US - RHINO R2 70212 05 1960 THE FABULOUS STYLE OF THE EBs (US) - CLP 3040 3. THE FABULOUS STYLE OF THE EBs - RHINO R2 70213 *2 THE FABULOUS STYLE OF THE EBs (UK) - HA-A2266 *3 *2 Essentially the UK vinyl version PLUS 'Let It Be Me' & 'Since You Broke My Heart' *3 The UK (LONDON) version differs in track listing from the US and as with the UK vinyl includes 'one o'clock' 'Poor Jenny' version. 4. CLASSIC EVERLY BROTHERS - BEAR FAMILY BOX SET - BCD 15618 03 1985 ALL THEY HAD TO DO WAS DREAM - RHINO RNLP 214 5. -

Wake up Little Susie Guitar Tab

WAKE UP LITTLE SUSIE As recorded by The Everly Brothers (Released as a Single in 1957) Transcribed by Christopher D. Words and Music by Boudleaux and Felice Cuppan Bryant Arranged by Donald and Phillip Everly D F G Gadd9 Dsus4 A E7 A7 D7 D9 F6/C xx 2 fr. 3 fr. xx x x x x 3 fr. x x 4 fr. x A Introduction Please Turn Off Metronome - Full Drum Score Transcribed Guitar II Tuned Dropped-D [D,A,D,G,B,E] Moderate Rockabilly = 190 ( D ) P P P CP PR D F G F TD F G F 1 g U U U W V V V V I g 4 U U U W V V V V U U U W V V V V Gtr II mfU U U W mpV V V V 2 (2) 2 (2) 2 2 2 2 T G3 (3) G3 (3) G3 K3 G3 K3 K2 (2) K2 (2) K2 K2 K2 K2 A K0 (0) K0 (0) K0 K0 K0 K0 B K0 (0) K0 (0) K0 K0 K0 K0 K0 (0) K0 (0) K0 K0 K0 K0 K K K LK K LK c c X X g 4 V V V V V V V V fV } V } V V V V V V V V V V fV } V } V V I g 4 V V V V V V V V ffV } V } V V V V V V V V V V ffV } V } V V V V V V V V V V f V N} V } V V V V V V V V V V f V N} V } V V Gtr III mp mf u mp mf u 2 1 x 3 x 1 1 2 1 x 3 x 1 1 T G3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 G1 x G3 x G1 K1 G3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 G1 x G3 x G1 K1 K2 K2 G2 K2 G2 K2 G2 K2 K2 x K4 x K2 K2 K2 K2 G2 K2 G2 K2 G2 K2 K2 x K4 x K2 K2 A K0 K0 K0 K0 K0 K0 K0 K0 K3 x K5 x K3 K3 K0 K0 K0 K0 K0 K0 K0 K0 K3 x K5 x K3 K3 B K LK K LK K LK K LK K3 x K5 x K3 K3 K LK K LK K LK K LK K3 x K5 x K3 K3 K K K K LK K K K K LK Public Domain Generated using the Power Tab Editor by Brad Larsen. -

Jukebox Decades

JUKEBOX DECADES – 100 HITS Rock Jukebox D1 Disc One - Title Artist Disc Two - Title Artist 01 Don’t Stop Believin’ Journey 01 The Final Countdown Europe 02 More Than A Feeling Boston 02 Bat Out Of Hell Meat Loaf 03 Eye Of The Tiger Survivor 03 Breaking The Law Judas Priest 04 (Don’t Fear) The Reaper Blue Oyster Cult 04 Danger Zone Kenny Loggins 05 Piece Of My Heart Big Brother 05 Message In A Bottle Gillian 06 Walk On The Wild Side Lou Reed 06 Poison Alice Cooper 07 All The Young Dudes Mott The Hoople 07 Mighty Wings Cheap Trick 08 God Gave Rock & Roll To You Argent 08 Take It On The Run REO Speedwagon 09 Dogs Of War Saxon 09 Beginning Of The End Status Quo 10 Because The Night Patti Smith 10 The Battle Rages On Deep Purple 11 Leave A Light On Belinda Carlisle 11 Burnin’ For You Blue Oyster Cult 12 Walk This Way RUN – DMC & Aerosmith 12 You’re The Voice John Farnham 13 Broken Wings Mr Mister 13 Kyrie Mr Mister 14 Summer In The City The Lovin’ Spoonful 14 Hold On Baby J J Cale 15 Africa Toto 15 Rock ‘N Me The Steve Miller Band 16 Making Love Out Of Nothing At Air Supply 16 Call On Me Captain Beefheart All 17 Dust In The Wind Kansas 17 No Time The Guess Who 18 Fantasy Aldo Nova 18 Jessie’s Girl Rick Springfield 19 Soul Sacrifice Santana 19 Johnny B Goode Johnny Winter 20 Albatross Fleetwood Mac 20 I Think I Love You Too Much Jeff Healey Disc Three - Title Artist Disc Four - Title Artist 01 Black Magic Woman Fleetwood Mac 01 King Of Dreams Deep Purple 02 Little Wing Stevie Ray Vaughan 02 Rock The Night Europe 03 She’s Not There Santana 03 Wasted In America Love/Hate 04 Turtle Blues Big Brother 04 Search & Destroy Iggy & The Stooges 05 Cause We’ve Ended As Lovers Jeff Beck 05 Living After Midnight Judas Priest 06 Nantucket Sleighride Mountain 06 Solid Ball Of Rock Saxon 07 Eight Miles High Byrds 07 Black Betty Ram Jam 08 American Woman The Guess Who 08 You Took The Words Right Out.