Video Games and Moral Panic from 1992 to 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concert and Music Performances Ps48

J S Battye Library of West Australian History Collection CONCERT AND MUSIC PERFORMANCES PS48 This collection of posters is available to view at the State Library of Western Australia. To view items in this list, contact the State Library of Western Australia Search the State Library of Western Australia’s catalogue Date PS number Venue Title Performers Series or notes Size D 1975 April - September 1975 PS48/1975/1 Perth Concert Hall ABC 1975 Youth Concerts Various Reverse: artists 91 x 30 cm appearing and programme 1979 7 - 8 September 1979 PS48/1979/1 Perth Concert Hall NHK Symphony Orchestra The Symphony Orchestra of Presented by The 78 x 56 cm the Japan Broadcasting Japan Foundation and Corporation the Western Australia150th Anniversary Board in association with the Consulate-General of Japan, NHK and Hoso- Bunka Foundation. 1981 16 October 1981 PS48/1981/1 Octagon Theatre Best of Polish variety (in Paulos Raptis, Irena Santor, Three hours of 79 x 59 cm Polish) Karol Nicze, Tadeusz Ross. beautiful songs, music and humour 1989 31 December 1989 PS48/1989/1 Perth Concert Hall Vienna Pops Concert Perth Pops Orchestra, Musical director John Vienna Singers. Elisa Wilson Embleton (soprano), John Kessey (tenor) Date PS number Venue Title Performers Series or notes Size D 1990 7, 20 April 1990 PS48/1990/1 Art Gallery and Fly Artists in Sound “from the Ros Bandt & Sasha EVOS New Music By Night greenhouse” Bodganowitsch series 31 December 1990 PS48/1990/2 Perth Concert Hall Vienna Pops Concert Perth Pops Orchestra, Musical director John Vienna Singers. Emma Embleton Lyons & Lisa Brown (soprano), Anson Austin (tenor), Earl Reeve (compere) 2 November 1990 PS48/1990/3 Aquinas College Sounds of peace Nawang Khechog (Tibetan Tour of the 14th Dalai 42 x 30 cm Chapel bamboo flute & didjeridoo Lama player). -

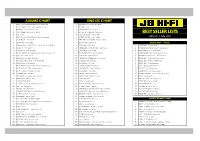

Best Seller Lists

ALBUMS CHART SINGLES CHART 1 NICK CAVE & THE BAD SEEDS - Dig Lazarus Dig 1 RIHANNA - Don't Stop The Music 2 JACK JOHNSON - Sleep Through The Static 2 FLORIDA - Low 3 RIHANNA - Good Girl Gone Bad 3 LEONA LEWIS - Bleeding Love 4 AMY WINEHOUSE - Back To Black 4 SOULJA BOY TELL EM - Crank That BEST SELLER LISTS 5 OST - Juno 5 THE VERONICAS - Untouched 6 MICHAEL JACKSON - Thriller (25th Anniversary) 6 BRITNEY SPEARS - Piece Of Me (Week 1 March) 7 GOLDFRAPP - Seventh Tree 7 THE LAST GOODNIGHT - Pictures Of You 8 DAFT PUNK - Alive 2007 8 KAT DELUNA - Whine Up DVD CHART - MUSIC 9 SARAH BLASKO - What The Sea Wants The Sea Will Have 9 KYLIE MINOGUE - Wow 1 ANDRE RIEU - Live In Vienna 10 FAKER - Be The Twilight 10 TIMBALAND / ONE REPUBLIC - Apologize 2 CHRISTINA AGUILERA - Back To Basics Live 11 THE PANICS - Cruel Guards 11 THE PRESETS - My People 3 IRON MAIDEN - Live After Death 12 THE WOMBATS - Proudly Present A Guide To Love, Loss 12 THE POTBELLEEZ - Don't Hold Back 4 JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE - Futuresex/Loveshow 13 K.D. LANG - Watershed 13 CUT COPY - Lights & Music 5 MICHAEL JACKSON - Live In Bucharest 14 THE BLACK CROWES - Warpaint 14 TIMBALAND ft KERRI HILSON - Scream 6 ANDRE RIEU - At Schoenbrunn Vienna 15 ANGUS & JULIA STONE - A Book Like This 15 CHRIS BROWN - Kiss Kiss 7 ANDRE RIEU - New York Memories 16 RADIOHEAD - In Rainbows 16 ALICIA KEYS - No One 8 ANDRE RIEU - In Wonderland 17 THE GETAWAY PLAN - Other Voices Other Rooms 17 JANET JACKSON - Feedback 9 TOTO - Falling In Between Live 18 MATCHBOX 20 - Exile On Mainstream 18 ONE REPUBLIC - Stop -

Petrol Prices

BtN: Episode 3 Transcripts 02/03/10 On this week's Behind the News: Medics saving lives on the frontline. Out sports stars’ safety under the spotlight. And some sweet sounds from a new partnership. Hi I'm Nathan Bazley welcome to Behind the News. Also on the show today, Catherine gets behind the scenes and probably into big trouble at the circus. Insulation Reporter: Kirsty Bennett INTRO: But first up today, if you've tuned into the news lately, there's one face you may be seeing a lot. The Federal Environment Minister Peter Garrett has been getting drilled for a program he introduced to insulate homes. Four people have died and there've been house fires because of the problems. So why has insulation become such a danger? Kirsty went out in search of an explanation. KIRSTY BENNETT, REPORTER: You can't see it on the outside, but across the country millions of properties have it. It's insulation and it sits in the roof and the walls of your house. While it's out of sight, its effect is felt in every room. KIRSTY: There are lots of different types of insulation but these are the most popular ones. There's bulk insulation which is made out of products like glass-wool or sheep's wool and a metal one which is just like thick aluminium foil. Insulation helps keeps your house cool in summer and warm in winter. It's like a big thick blanket, which cuts down how much heat runs in, and out, of the house. -

The Company of Strangers: a Natural History of Economic Life

The Company of Strangers: A Natural History of Economic Life Paul Seabright Contents Page Preface: 2 Part I: Tunnel Vision Chapter 1: Who’s in Charge? 9 Prologue to Part II: 20 Part II: How is Human Cooperation Possible? Chapter 2: Man and the Risks of Nature 22 Chapter 3: Murder, Reciprocity and Trust 34 Chapter 4: Money and human relationships 48 Chapter 5: Honour among Thieves – hoarding and stealing 56 Chapter 6: Professionalism and Fulfilment in Work and War 62 Epilogue to Parts I and II: 71 Prologue to Part III: 74 Part III: Unintended Consequences Chapter 7: The City from Ancient Athens to Modern Manhattan 77 Chapter 8: Water – commodity or social institution? 88 Chapter 9: Prices for Everything? 98 Chapter 10: Families and Firms 110 Chapter 11: Knowledge and Symbolism 126 Chapter 12: Depression and Exclusion 139 Epilogue to Part III: 154 Prologue to Part IV: 155 Part IV: Collective Action Chapter 13: States and Empires 158 Chapter 14: Globalization and Political Action 169 Conclusion: How Fragile is the Great Experiment? 179 The Company of Strangers: A Natural History of Economic Life Preface The Great Experiment Our everyday life is much stranger than we imagine, and rests on fragile foundations. This is the startling message of the evolutionary history of humankind. Our teeming, industrialised, networked existence is not some gradual and inevitable outcome of human development over millions of years. Instead we owe it to an extraordinary experiment launched a mere ten thousand years ago*. No-one could have predicted this experiment from observing the course of our previous evolution, but it would forever change the character of life on our planet. -

Mat De Koning

A BAND OF BEST FRIENDS A ROADIE THAT WANTED ROCKSTARDOM A DOCUMENTARY TEN YEARS IN THE MAKING A film by Mat de Koning Produced by Brooke Silcox, Mat de Koning, Dave Kavanagh www.mealtickets.tv © 2016 Pick Productions Pty Ltd, ScreenWest Inc We’ve got hookers for you man, we got coke, we got crack, we got non-stop booze, we’re going to fly you in a private jet and we’ve got some meal tickets for “ you, Meal Tickets, WOO HOO!!! - Dave Kavanagh, 2005 ” DIRECTED BY MAT DE KONING PRODUCED BY BROOKE TIA SILCOX, MAT DE KONING AND DAVE KAVANAGH 93 MINUTES: COLOUR / BLACK AND WHITE: 4:3 / 16:9 COMPANY INFORMATION Pick Productions Pty Ltd 55 162 692 131 www.mealtickets.tv [email protected] + 61 412 696 467 [email protected] +61 439 481 084 MEAL TICKET 1. A card or ticket entitling the holder to a meal or meals. 2. Informal a person or thing depended on as a source of financial support. 1 slang a person, situation, etc, providing a source of livelihood or income 2 1 American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fifth Edition. Copyright © 2011 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved. 2 Collins English Dictionary – Complete and Unabridged, 12th Edition 2014 © HarperCollins Publishers 1991, 1994, 1998, 2000, 2003, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2011, 2014 TAGLINE There is no guide book to rock ‘n’ roll. LOGLINE A band of best friends, a roadie that wanted to be a rockstar, a documentary ten years in the making. -

Nber Working Paper Seres Understand~G Financial

NBER WORKING PAPER SERES UNDERSTAND~G FINANCIAL CRISES: A DEVELOPING COUNTRY PERSPECTIVE Frederic S. Mishkin Working Paper 5600 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 May 1996 Prepared for the World Bank Annual Conference on Development Economics, April 25-26, 1996, Washington, DC, I thank Agustin Carstens and the staff at the Bank of Mexico, Terry Checki, Marilyn Skiles, and participants at seminars at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the International Monetary Fund, the Interamerican Development Bank and the World Bank Development Conference for their helpful comments and Martina Heyd for research assistance. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the author. They do not necessarily represent the views of the World Bank, its Executive Directors, or the companies it represents, nor of Columbia University, the National Bureau of Economic Research, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. This paper is part of NBER’s research programs in Economic Fluctuations and Growth, and Monetary Economics. O 1996 by Frederic S. Mishkin, All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including O notice, is given to the source. NBER Working Paper 5600 May 1996 UNDERSTANDING FINANCIAL CRISES : A DEVELOPING COUNTRY PERSPECTIVE ABSTRACT This paper explains the puzzle of how a developing economy can shift dramatically from a path of reasonable growth before a financial crisis, as was the case in Mexico in 1994, to a sharp decline in economic activity after a crisis occurs. -

Mr John Hyde; Mr John Day

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY - Tuesday, 15 September 2009] p7065b-7066a Mr John Hyde; Mr John Day GOVERNMENT DEPARTMENTS AND AGENCIES — ON-HOLD TELEPHONY SYSTEMS 1424. Mr J.N. Hyde to the Minister for Planning; Culture and the Arts In relation to the Ministerial office and all associated portfolio agency offices: (a) what recorded music or radio station is broadcast on office on-hold telephony systems; (b) what fees are paid to the Australasian Performing Right Association (APRA), artists directly or any copyright bodies; and (c) who is the responsible officer for deciding selection of on-hold material? Mr J.H.D. DAY replied: Ministerial Office of Minister Day (a)-(c) Please refer to Legislative Assembly question on notice 1415 Department of Planning (a) None. (c) Not applicable. (d) The Department's communications manager is responsible for the scripting of on hold messages, including specific information for some business units. Midland Redevelopment Authority (a) 4 minutes of copyright free music. (b) $165 annual licence fee paid to M2 Technology. (c) Chief Executive Officer. Armadale Redevelopment (a) 720 AM (b) Nil (c) Executive Director East Perth Redevelopment; Subiaco Redevelopment Authority (a) EPRA and SRA do not use recorded music or a radio station to broadcast on office on-hold telephony systems. (b)-(c) Not applicable Department of Culture and the Arts; ScreenWest; Perth Theatre Trust (a) This Is How It's Meant to Be — Emily Barker, Something Special — The Sunshine Brothers, Call Of The Wild — Xave Brown, We'll Take a -

The Perth Voice West

The Perth thai restaurant “Perth’s Best Thai Food!” 348 Fitzgerald Street, North Perth Voiceo N 801 Saturday October 19, 2013 • Phone 9430 7727 • www.perthvoice.com • [email protected] P 9228 9307 Democra-sigh by DAVID BELL COUNCIL polls close 6pm Saturday October 19 Sammut clears shelves of but voters in Voiceland are hardly rushing to have The End their say in a year that’s a quarter-century in books “That put the kybosh also seen both a state and by DAVID BELL on selling the business,” federal election. WITH the bulldozer he says. As the Voice went to looming in the “I tried to sell the stock press, Perth city council’s but I was unsuccessful turnout was 28 per cent, background, Vincent mainly because I couldn’t Bayswater’s was a dismal Sammut’s having to fi nd a serious buyer. 21-odd, Stirling’s around 24 pack up his North Perth “Now time’s virtually and Vincent just north of 30 bookshop—and around run out... I have to be per cent. 50,000 books. out of here by the end of The average across all Formerly a graphic January but I will have to electorates is 24 per cent, designer he got out of close the doors before that one of the lowest turnouts in that game when told he to allow me to do some recent years according to the was overqualifi ed: “That’s concentrated packing.” WA electoral commission. code for ‘you’ve passed a He’s hoping a sale will Vincent candidate certain age’,” he says. -

The Perth Sound in the 1960S—

(This is a combined version of two articles: ‘‘Do You Want To Know A Secret?’: Popular Music in Perth in the Early 1960s’ online in Illumina: An Academic Journal for Performance, Visual Arts, Communication & Interactive Multimedia, 2007, available at: http://illumina.scca.ecu.edu.au/data/tmp/stratton%20j%20%20illumina%20p roof%20final.pdf and ‘Brian Poole and the Tremeloes or the Yardbirds: Comparing Popular Music in Perth and Adelaide in the Early 1960s’ in Perfect Beat: The Pacific Journal for Research into Contemporary Music and Popular Culture, vol 9, no 1, 2008, pp. 60-77). Brian Poole and the Tremeloes or the Yardbirds: Comparing Popular Music in Perth and Adelaide in the Early 1960s In this article I want to think about the differences in the popular music preferred in Perth and Adelaide in the early 1960s—that is, the years before and after the Beatles’ tour of Australia and New Zealand, in June 1964. The Beatles played in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane and Adelaide but not in Perth. In spite of this, the Beatles’ songs were just as popular in Perth as in the other major cities. Through late 1963 and 1964 ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand,’ ‘I Saw Her Standing There,’ ‘Roll Over Beethoven’ and the ‘All My Loving’ EP all reached the number one position in the Perth chart as they did nationally.1 In this article, though, I am not so much interested in the Beatles per se but rather in their indexical signalling of a transformation in popular music tastes. As Lawrence Zion writes in an important and surprisingly neglected article on ‘The impact of the Beatles on pop music in Australia: 1963-1966:’ ‘For young Australians in the early 1960s America was the icon of pop music and fashion.’2 One of the reasons Zion gives for this is the series of Big Shows put on by American entrepreneur Lee Gordon through the second half of the 1950s. -

Recovery Hearing Voices Helen Morton MLC Walking Towards Recovery Music and Anti-Stigma Finding a Home

head head Autumn 2009 FREE Magazine of WA Mental Health Recovery Hearing Voices Helen Morton MLC Walking Towards Recovery Music and Anti-stigma Finding a Home Contents Contents Headlines Feature Hearing Voices 4 The theme of this edition is recovery. My Story of Recovery 7 You will gather from the articles that Helen Morton MLC 8 recovery is a journey that is distinct WA Mental Health Reforms 9 for each individual. Recovery means Journeys Flying Overdownunder 10 more than simply the absence of Walking Towards Recovery 11 illness; it encompasses a person’s Anti-stigma WA Musicians Voice an 13 Anti-stigma Message mental and physical wellbeing, social participation and acceptance, Reform Looking Back, Looking Forward 14 development of resilience, sense of Finding a Home 15 Addressing Homelessness 15 meaning and hope. New Research Loneliness, a Harsh Reality 16 Hon Helen Morton MLC, Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister From the Neck Down 16 for Mental Health, who launched Head2Head and is pictured Unlocking the History of Graylands 17 here with me, informs us in our feature profile about new State Metabolic Syndrome 17 Government initiatives to assist in recovery. Tried and Tested Gratitude Journal 18 The magazine also highlights the importance of artistic Meditation and Me 18 Joy Walking 19 creation and music as positive forms of expression, coping and connection. Consumer Participation A Portrait of Art Therapy in WA 20 Proving the Practice 21 The cover artwork is by Perth sculptor Simon Gilby. According to Empowering Consumers 21 Simon, the piece, entitled “Leap,” is “about the transition from Thriving, Not Just Surviving 22 one place to another, the dark unknown, a leap of faith and the Growing Towards Wellness 23 hope of resurrection. -

Nber Working Paper Series

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES AN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE ON THE QUEST FOR FINANCIAL STABILITY AND THE MONETARY POLICY REGIME Michael D. Bordo Working Paper 24154 http://www.nber.org/papers/w24154 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 December 2017 For excellent research assistance I thank Maria Sole Pagliari of Rutgers University. For helpful comments and suggestions, I thank: Chris Meissner, Pierre Siklos, Harold James, Hugh Rockoff, Eugene White, John Landon Lane, John Taylor, Myron Scholes, Gavin Wright, Paul David, Lars E.O. Svennson, Aaron Tornell and David Wheelock. The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer-reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2017 by Michael D. Bordo. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. An Historical Perspective on the Quest for Financial Stability and the Monetary Policy Regime Michael D. Bordo NBER Working Paper No. 24154 December 2017 JEL No. E3,E42,G01,N1,N2 ABSTRACT This paper surveys the co-evolution of monetary policy and financial stability for a number of countries across four exchange rate regimes from 1880 to the present. I present historical evidence on the incidence, costs and determinants of financial crises, combined with narratives on some famous financial crises. -

Bury Me Deep in Isolation: a Cultural Examination of a Peripheral Music Industry and Scene

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Research Online @ ECU Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 2013 Bury me deep in isolation: A cultural examination of a peripheral music industry and scene Christina Ballico Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses Part of the Arts Management Commons, and the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Ballico, C. (2013). Bury me deep in isolation: A cultural examination of a peripheral music industry and scene. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/682 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/682 Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 2013 Bury me deep in isolation: A cultural examination of a peripheral music industry and scene Christina Ballico Edith Cowan University Recommended Citation Ballico, C. (2013). Bury me deep in isolation: A cultural examination of a peripheral music industry and scene. Retrieved from http://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/682 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. http://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/682 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement.