COIN USE in and AROUND MILITARY CAMPS on the LOWER-RHINE: NIJMEGEN - KOPS PLATEAU by JOS P.A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Index

General Index Italicized page numbers indicate figures and tables. Color plates are in- cussed; full listings of authors’ works as cited in this volume may be dicated as “pl.” Color plates 1– 40 are in part 1 and plates 41–80 are found in the bibliographical index. in part 2. Authors are listed only when their ideas or works are dis- Aa, Pieter van der (1659–1733), 1338 of military cartography, 971 934 –39; Genoa, 864 –65; Low Coun- Aa River, pl.61, 1523 of nautical charts, 1069, 1424 tries, 1257 Aachen, 1241 printing’s impact on, 607–8 of Dutch hamlets, 1264 Abate, Agostino, 857–58, 864 –65 role of sources in, 66 –67 ecclesiastical subdivisions in, 1090, 1091 Abbeys. See also Cartularies; Monasteries of Russian maps, 1873 of forests, 50 maps: property, 50–51; water system, 43 standards of, 7 German maps in context of, 1224, 1225 plans: juridical uses of, pl.61, 1523–24, studies of, 505–8, 1258 n.53 map consciousness in, 636, 661–62 1525; Wildmore Fen (in psalter), 43– 44 of surveys, 505–8, 708, 1435–36 maps in: cadastral (See Cadastral maps); Abbreviations, 1897, 1899 of town models, 489 central Italy, 909–15; characteristics of, Abreu, Lisuarte de, 1019 Acequia Imperial de Aragón, 507 874 –75, 880 –82; coloring of, 1499, Abruzzi River, 547, 570 Acerra, 951 1588; East-Central Europe, 1806, 1808; Absolutism, 831, 833, 835–36 Ackerman, James S., 427 n.2 England, 50 –51, 1595, 1599, 1603, See also Sovereigns and monarchs Aconcio, Jacopo (d. 1566), 1611 1615, 1629, 1720; France, 1497–1500, Abstraction Acosta, José de (1539–1600), 1235 1501; humanism linked to, 909–10; in- in bird’s-eye views, 688 Acquaviva, Andrea Matteo (d. -

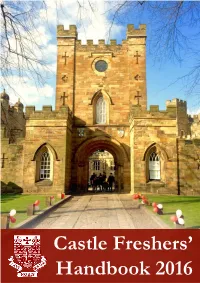

Castle Freshers' Handbook 2016

Castle Freshers’ Handbook 2016 2 Contents Welcome - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 4 Your JCR Executive Committee - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 6 Your International Freshers’ Representatives - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 11 Your Male Freshers’ Representatives - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -13 Your Female Freshers’ Representatives- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 15 Your Welfare Team - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 17 Your Non-Executive Officers - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 21 JCR Meetings - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 24 College Site Plan - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 25 Accommodation in College - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -27 What to bring to Durham - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -28 College Dictionary - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 29 The Key to the Lowe Library - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 31 Social life in Durham - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 33 Our College’s Sports - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 36 Our College’s Societies - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -46 Durham Students’ Union and Team Durham - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 52 General -

1 the DUTCH DELTA MODEL for POLICY ANALYSIS on FLOOD RISK MANAGEMENT in the NETHERLANDS R.M. Slomp1, J.P. De Waal2, E.F.W. Ruijg

THE DUTCH DELTA MODEL FOR POLICY ANALYSIS ON FLOOD RISK MANAGEMENT IN THE NETHERLANDS R.M. Slomp1, J.P. de Waal2, E.F.W. Ruijgh2, T. Kroon1, E. Snippen2, J.S.L.J. van Alphen3 1. Ministry of Infrastructure and Environment / Rijkswaterstaat 2. Deltares 3. Staff Delta Programme Commissioner ABSTRACT The Netherlands is located in a delta where the rivers Rhine, Meuse, Scheldt and Eems drain into the North Sea. Over the centuries floods have been caused by high river discharges, storms, and ice dams. In view of the changing climate the probability of flooding is expected to increase. Moreover, as the socio- economic developments in the Netherlands lead to further growth of private and public property, the possible damage as a result of flooding is likely to increase even more. The increasing flood risk has led the government to act, even though the Netherlands has not had a major flood since 1953. An integrated policy analysis study has been launched by the government called the Dutch Delta Programme. The Delta model is the integrated and consistent set of models to support long-term analyses of the various decisions in the Delta Programme. The programme covers the Netherlands, and includes flood risk analysis and water supply studies. This means the Delta model includes models for flood risk management as well as fresh water supply. In this paper we will discuss the models for flood risk management. The issues tackled were: consistent climate change scenarios for all water systems, consistent measures over the water systems, choice of the same proxies to evaluate flood probabilities and the reduction of computation and analysis time. -

Acipenser Sturio L., 1758) in the Lower Rhine River, As Revealed by Telemetry Niels W

Outmigration Pathways of Stocked Juvenile European Sturgeon (Acipenser Sturio L., 1758) in the Lower Rhine River, as Revealed by Telemetry Niels W. P. Brevé, Hendry Vis, Bram Houben, André Breukelaar, Marie-Laure Acolas To cite this version: Niels W. P. Brevé, Hendry Vis, Bram Houben, André Breukelaar, Marie-Laure Acolas. Outmigration Pathways of Stocked Juvenile European Sturgeon (Acipenser Sturio L., 1758) in the Lower Rhine River, as Revealed by Telemetry. Journal of Applied Ichthyology, Wiley, 2019, 35 (1), pp.61-68. 10.1111/jai.13815. hal-02267361 HAL Id: hal-02267361 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02267361 Submitted on 19 Aug 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Received: 5 December 2017 | Revised: 26 April 2018 | Accepted: 17 September 2018 DOI: 10.1111/jai.13815 STURGEON PAPER Outmigration pathways of stocked juvenile European sturgeon (Acipenser sturio L., 1758) in the Lower Rhine River, as revealed by telemetry Niels W. P. Brevé1 | Hendry Vis2 | Bram Houben3 | André Breukelaar4 | Marie‐Laure Acolas5 1Koninklijke Sportvisserij Nederland, Bilthoven, Netherlands Abstract 2VisAdvies BV, Nieuwegein, Netherlands Working towards a future Rhine Sturgeon Action Plan the outmigration pathways of 3ARK Nature, Nijmegen, Netherlands stocked juvenile European sturgeon (Acipenser sturio L., 1758) were studied in the 4Rijkswaterstaat (RWS), Rotterdam, River Rhine in 2012 and 2015 using the NEDAP Trail system. -

1 Settlement Patterns in Roman Galicia

Settlement Patterns in Roman Galicia: Late Iron Age – Second Century AD Jonathan Wynne Rees Thesis submitted in requirement of fulfilments for the degree of Ph.D. in Archaeology, at the Institute of Archaeology, University College London University of London 2012 1 I, Jonathan Wynne Rees confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Abstract This thesis examines the changes which occurred in the cultural landscapes of northwest Iberia, between the end of the Iron Age and the consolidation of the region by both the native elite and imperial authorities during the early Roman empire. As a means to analyse the impact of Roman power on the native peoples of northwest Iberia five study areas in northern Portugal were chosen, which stretch from the mountainous region of Trás-os-Montes near the modern-day Spanish border, moving west to the Tâmega Valley and the Atlantic coastal area. The divergent physical environments, different social practices and political affinities which these diverse regions offer, coupled with differing levels of contact with the Roman world, form the basis for a comparative examination of the area. In seeking to analyse the transformations which took place between the Late pre-Roman Iron Age and the early Roman period historical, archaeological and anthropological approaches from within Iberian academia and beyond were analysed. From these debates, three key questions were formulated, focusing on -

De 18E/19E Eeuwse Hoogovenvervuilinglaag in De Oude Ijsselafzettingen Bij Drempt

De 18e/19e eeuwse hoogovenvervuilinglaag in de Oude IJsselafzettingen bij Drempt Afstudeerscriptie LAD-80424 Student: F.R.P.M. Miedema Studentnr: 700411‐571‐080 Leerstoelgroep: Landdynamiek (LAD) Datum: November 2009 De 18e/19e eeuwse hoogovenvervuilingslaag in de Oude IJsselafzettingen bij Drempt Afstudeerscriptie LAD-80424 Examinator: Prof. dr. ir. A. Veldkamp Begeleiders: dr. J.M. Schoorl dr. Ir. M.W. van der Berg Student: ing. F.R.P.M. Miedema Studentnr: 700411‐571‐080 Leerstoelgroep: Landdynamiek (LAD) Datum: November 2009 De ijzerhut in ’t woud. Waaruit de koolstoom, dik en zwart, Het groen verkleurt van ’t hout. Daar spatten vonken, wijd en zijd, Daar zwoegt men, zweet en stookt altijd, En laat altijd de balgen blazen, Als moest men berg en rots verglazen. Schiller, 1797, Gang nach den Eisenhammer. Colofon Auteur: ing. F.R.P.M. Miedema Veldwerk: ing. F.R.P.M. Miedema Copyright: Wageningen Universiteit, leerstoelgroep Landdynamiek & F.R.P.M. Miedema Afbeelding omslag I: Reconstructie van de hoogoven met ijzergieterij in Ulft in de 18de eeuw door W. Gilles uit 1953 (WGIJ, 2007) Afbeelding omslag II: Foto van aangekraste bodemlagen in proefput 3 (28-07-2009). De proefput bevindt zich in een maïsperceel ten noorden van het Oude IJsselkanaal, op het perceel genaamd Stockhovens Land bij Drempt. Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden verveelvoudigd en/of openbaar gemaakt door middel van druk, fotokopie, microfilm of op welke andere wijze dan ook, zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de Wageningen Universiteit, Leerstoelgroep Landdynamiek en F.R.P.M. Miedema. De 18de/19de eeuwse hoogovenvervuilinglaag in de Oude IJsselafzettingen bij Drempt Administratieve gegevens Onderzoekgegevens Datum opdracht WUR 13 mei 2008 Periode uitvoering veldwerk 6 juni 2008 tot 29 augustus 2008 Datum rapportage 23 november 2009 Uitvoerder ing. -

North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) / India

Page 1 of 13 Consulate General of India Frankfurt *** General and Bilateral Brief- North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) / India North Rhine-Westphalia, commonly shortened to NRW is the most populous state of Germany, with a population of approximately 18 million, and the fourth largest by area. It was formed in 1946 as a merger of the provinces of North Rhine and Westphalia, both formerly parts of Prussia, and the Free State of Lippe. Its capital is Düsseldorf; the largest city is Cologne. Four of Germany's ten largest cities—Cologne, Düsseldorf, Dortmund, and Essen— are located within the state, as well as the second largest metropolitan area on the European continent, Rhine-Ruhr. NRW is a very diverse state, with vibrant business centers, bustling cities and peaceful natural landscapes. The state is home to one of the strongest industrial regions in the world and offers one of the most vibrant cultural landscapes in Europe. Salient Features 1. Geography: The state covers an area of 34,083 km2 and shares borders with Belgium in the southwest and the Netherlands in the west and northwest. It has borders with the German states of Lower Saxony to the north and northeast, Rhineland-Palatinate to the south and Hesse to the southeast. Thinking of North Rhine-Westphalia also means thinking of the big rivers, of the grassland, the forests, the lakes that stretch between the Eifel hills and the Teutoburg Forest range. The most important rivers flowing at least partially through North Rhine-Westphalia include: the Rhine, the Ruhr, the Ems, the Lippe, and the Weser. -

Anthropogenic Organic Contaminants in Sediments of the Lippe River, Germany Alexander Kronimus*, Jan Schwarzbauer, Larissa Dsikowitzky, Sabine Heim, Ralf Littke

ARTICLE IN PRESS Water Research 38 (2004) 3473–3484 Anthropogenic organic contaminants in sediments of the Lippe river, Germany Alexander Kronimus*, Jan Schwarzbauer, Larissa Dsikowitzky, Sabine Heim, Ralf Littke Institute of Geology and Geochemistry of Petroleum and Coal, RWTH Aachen University, Lochnerstrasse 4-20, D-52056 Aachen, Germany Received 13 August 2003; received in revised form 27 January2004; accepted 8 April 2004 Abstract Sediment samples of the Lippe river (Germany) taken between August 1999 and March 2001 were investigated by GC–MS-analyses. These analyses were performed as non-target-screening approaches in order to identify a wide range of anthropogenic organic contaminants. Unknown contaminants like 3,6-dichlorocarbazole and bis(4-octylphenyl) amine as well as anthropogenic molecular marker compounds were selected for quantification. The obtained qualitative and quantitative analytical results were interpreted in order to visualize the anthropogenic contamination of the Lippe river including spatial distribution, input effects and time dependent occurrence. Anthropogenic molecular markers derived from municipal sources like polycyclic musks, 4-oxoisophorone and methyltriclosan as well as from agricultural sources (hexachlorobenzene) were gathered. In addition molecular markers derived from effluents of three different industrial branches, e.g. halogenated organics, tetrachlorobenzyltoluenes and tetrabutyltin, were identified. While municipal and agricultural contaminations were ubiquitous and diffusive, industrial emission -

The Present Status of the River Rhine with Special Emphasis on Fisheries Development

121 THE PRESENT STATUS OF THE RIVER RHINE WITH SPECIAL EMPHASIS ON FISHERIES DEVELOPMENT T. Brenner 1 A.D. Buijse2 M. Lauff3 J.F. Luquet4 E. Staub5 1 Ministry of Environment and Forestry Rheinland-Pfalz, P.O. Box 3160, D-55021 Mainz, Germany 2 Institute for Inland Water Management and Waste Water Treatment RIZA, P.O. Box 17, NL 8200 AA Lelystad, The Netherlands 3 Administrations des Eaux et Forets, Boite Postale 2513, L 1025 Luxembourg 4 Conseil Supérieur de la Peche, 23, Rue des Garennes, F 57155 Marly, France 5 Swiss Agency for the Environment, Forests and Landscape, CH 3003 Bern, Switzerland ABSTRACT The Rhine basin (1 320 km, 225 000 km2) is shared by nine countries (Switzerland, Italy, Liechtenstein, Austria, Germany, France, Luxemburg, Belgium and the Netherlands) with a population of about 54 million people and provides drinking water to 20 million of them. The Rhine is navigable from the North Sea up to Basel in Switzerland Key words: Rhine, restoration, aquatic biodiversity, fish and is one of the most important international migration waterways in the world. 122 The present status of the river Rhine Floodplains were reclaimed as early as the and groundwater protection. Possibilities for the Middle Ages and in the eighteenth and nineteenth cen- restoration of the River Rhine are limited by the multi- tury the channel of the Rhine had been subjected to purpose use of the river for shipping, hydropower, drastic changes to improve navigation as well as the drinking water and agriculture. Further recovery is discharge of water, ice and sediment. From 1945 until hampered by the numerous hydropower stations that the early 1970s water pollution due to domestic and interfere with downstream fish migration, the poor industrial wastewater increased dramatically. -

The Rhine River Crossings by Barry W

The Rhine River Crossings by Barry W. Fowle Each of the Allied army groups had made plans for the Rhine crossings. The emphasis of Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) planning was in the north where the Canadians and British of Field Marshal Bernard L. Montgomery's 21st Army Group were to be the first across, followed by the Ninth United States Army, also under Montgomery. Once Montgomery crossed, the rest of the American armies to the south, 12th Army Group under General Omar N. Bradley and 6th Army Group under General Jacob L. Devers, would cross. On 7 March 1945, all that Slegburg changed. The 27th Armored Infantry Battalion, Combat Beuel Command B, 9th Armored Division, discovered that the Ludendorff bridge at 9th NFANR " Lannesdorf I0IV R Remagen in the First Army " Mehlem Rheinbach area was still standing and Oberbachem = : kum h RM Gelsd srn passed the word back to the q 0o~O kiVl 78th e\eaeo Combat Command B com- INP L)IV Derna Ahweile Llnz mander, Brigadier General SInzig e Neuenahi Helmershelm William M. Hoge, a former G1 Advance to the Rhine engineer officer. General 5 10 Mile Brohl Hoge ordered the immediate capture of the bridge, and Advance to the Rhine soldiers of the 27th became the first invaders since the Napoleonic era to set foot on German soil east of the Rhine. Crossings in other army areas followed before the month was. over leading to the rapid defeat of Hitler's armies in a few short weeks. The first engineers across the Ludendorff bridge were from Company B, 9th Armored Engineer Battalion (AEB). -

Flüsse in NRW Wasserstraßen Durchs Land

Flüsse in NRW Wasserstraßen durchs Land Die Reihe "Alle Augen Auf..." lenkt dieses Mal den Fokus auf Flüsse in Nordrhein-Westfalen und beantwortet unter anderem folgende Fragen: Hat die Weser eigentlich eine Quelle? Woher kommt der Name "Ruhr"? Und ist der Rhein wirklich der längste Fluss in NRW? Menschen aus Nordrhein-Westfalen erzählen interessante, unterhaltende und spannende Geschichten über "ihren" Fluss. Lippe - 220 km Wer hat's gewusst? Nicht der Rhein, sondern die Lippe ist der längste Fluss in Nordrhein-Westfalen! Die Quelle entspringt in Bad Lippspringe, fließt dann auf 220 Kilometern durch NRW, bis sie sich bei Wesel mit dem Rhein vereint. Die Entstehung des Flusses umgibt eine Sage: Der nordische Gott Odin soll ein Auge geopfert haben, um dem trockenen Gebiet am Fuße des Teutoburger Waldes Leben zu schenken. Odins Auge - so wird die Quelle der Lippe deswegen auch genannt. Schon die Römer zog es an die Lippe und sie nutzten das Wasser, um ihre Güter zu transportieren. Und so ist die Römerroute entlang der Lippe eine weitere Besonderheit. Lange Zeit war die Wasserqualität der Lippe eher mäßig. In den 60er Jahren wurde daher künstlicher Sauerstoff in den Fluß gepumpt. Eine reichlich aufwändige Sache und nur von kurzem Erfolg. Langfristig heißt das Zauberwort "Renaturierung". Das bedeutet konkret: das Wasser zu säubern und den Fluss wieder mit seinen natürlichen Auen zu umgeben. Pate : Ulrich Detering arbeitet in Lippstadt als Wasserbauingenieur. Obwohl er gebürtig von der Weser kommt, ist er ein leidenschaftlicher Lippstädter und liebt das "Venedig Westfalens". Weitere Informationen : www.roemerlipperoute.de www.eglv.de/lippeverband/lippe Ruhr - 219 km Der 219,3 Kilometer lange Fluss ist namensgebend für eine ganze Region: das Ruhrgebiet. -

About an Early Medieval Settlement in the South of Ancient Tomis

ABOUT AN EARLY MEDIEVAL SETTLEMENT IN THE SOUTH OF ANCIENT TOMIS Cristina Paraschiv-Talmaţchi DOI: 10.17846/CL.2018.11.1.3-15 Abstract: PARASCHIV-TALMAŢCHI, Cristina. About an early medieval settlement in the south of ancient Tomis. The author makes a brief presentation of the discoveries from the tenth – eleventh century on the territory of Constanța (Constanța County, Romania; Pl. 1: 1), in the perimeter of the ancient settlement of Tomis. Based on these discoveries, it has been assumed until the present the existence of an early medieval settlement named Constantia, approximately within the same limits mentioned in the Byzantine literary sources. Related to the results of new discoveries in 2017, and comparing Tomis archaeological area with the discoveries in the researched site, we suggest a new location of the settlement of Constantia. It lies near a castellum of the stone vallum, in a protected area by the defensive line. Probably the new location of the settlement determined the reason for the Byzantine literary sources to mention it with a new name and not with the former toponym Tomis. Keywords: settlement, Constantia, seals, ceramics, the 10th – 11th centuries, Dobrudja Abstrakt: PARASCHIV-TALMAŢCHI, Cristina. O včasnostredovekom osídlení na juh od an- tického mesta Tomis. Autorka podáva krátku prezentáciu nálezov z 10. až 11. storočia na úze- mí dnešného mesta Konstanca (župa Konstanca, Rumunsko; Pl. 1: 1), na hranici niekdajšie- ho antického osídlenia mesta Tomis. Na základe týchto objavov sa do dneška predpokladá existencia včasnostredovekého osídlenia, nazývaného Constancia, približne v rámci rovna- kých hraníc, ako sú uvedené v byzantských písomných prameňoch.