9 April 1954 Special Distribution INTERNATIONA! TRADE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

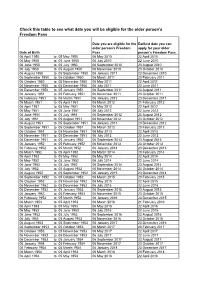

Copy of Age Eligibility from 6 April 10

Check this table to see what date you will be eligible for the older person's Freedom Pass Date you are eligible for the Earliest date you can older person's Freedom apply for your older Date of Birth Pass person's Freedom Pass 06 April 1950 to 05 May 1950 06 May 2010 22 April 2010 06 May 1950 to 05 June 1950 06 July 2010 22 June 2010 06 June 1950 to 05 July 1950 06 September 2010 23 August 2010 06 July 1950 to 05 August 1950 06 November 2010 23 October 2010 06 August 1950 to 05 September 1950 06 January 2011 23 December 2010 06 September 1950 to 05 October 1950 06 March 2011 20 February 2011 06 October 1950 to 05 November 1950 06 May 2011 22 April 2011 06 November 1950 to 05 December 1950 06 July 2011 22 June 2011 06 December 1950 to 05 January 1951 06 September 2011 23 August 2011 06 January 1951 to 05 February 1951 06 November 2011 23 October 2011 06 February 1951 to 05 March 1951 06 January 2012 23 December 2011 06 March 1951 to 05 April 1951 06 March 2012 21 February 2012 06 April 1951 to 05 May 1951 06 May 2012 22 April 2012 06 May 1951 to 05 June 1951 06 July 2012 22 June 2012 06 June 1951 to 05 July 1951 06 September 2012 23 August 2012 06 July 1951 to 05 August 1951 06 November 2012 23 October 2012 06 August 1951 to 05 September 1951 06 January 2013 23 December 2012 06 September 1951 to 05 October 1951 06 March 2013 20 February 2013 06 October 1951 to 05 November 1951 06 May 2013 22 April 2013 06 November 1951 to 05 December 1951 06 July 2013 22 June 2013 06 December 1951 to 05 January 1952 06 September 2013 23 August 2013 06 -

Survey of Current Business September 1953

SEPTEMBER 1953 U. S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE OFFICE OF BUSINESS ECONOMICS SURVEY OF CUKMENT BUSINESS DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE FIELD SERVICE Albuquerque, N. Mez. Los Angeles 15, Calif. No. 9 204 S. 10th St. 112 West 9th St. SEPTEMBER 1953 Atlanta 3, Ga. Memphis 3, Tenn. 86 Forsyth St. NW. 229 Federal BIdg. Boston 9, Mass. Miami 32' FIa' 261 Franklin St. 36 NE' Fir8t St' Minneapolis 2, Minn. Buffalo 3, N. Y. 607 Marquette Are, 117 Silicon St. New Orleans 12, La. Charleston 4, S. C. Area 2. 333 St. Charles Are. PAGE Sergeant Jasper Bldf. New York 13. N. Y. THE BUSINESS SITUATION 1 Cheyenne, Wyo. 346 Broadway 307 Federal Office Bldf. Capital Goods Demand in Late 1953 . 3 Philadelphia 7, Pa. Trends in Retail Sales . 5 Chicago 1, III. 1015 Chestnut St. 221 N. LaSalle St. The Volume of Government Purchasing ... 9 Phoenix, Ariz. 137 N. Second Ave. Balance of Payments Cincinnati 2. Ohio 105 W. Fourth St, During the Second Quarter ........ 11 Pittsburgh 22, Pa. 717 Liberty Are. Cleveland 14, Ohio 925 Euclid AT* Portland 4, Oreg. * * * 520 SW. Morrison Sj, Dallas 2, Tes. 1114 Commerce Si, SPECIAL ARTICLES Reno, NOT. 1479 Wells Are. Changes in Public and Private Debt . 13 Denver 2, Colo. 142 New Custom House Transportation in the Balance of Payments . 20 Richmond, Va. 409 East Main St. Detroit 26, Mich. * * * 1214 Griawold St. St. Louis 1, Mo. 1114 Market St* El Paso, Tex. MONTHLY BUSINESS STATISTICS . S-l to S-40 Chamber of Commerce Salt Lake City 1, Utah Statistical Index ....... Inside back cover Bldg. -

City of Corpus Christi Former City Managers 1852 - Present

City of Corpus Christi Former City Managers 1852 - Present Council/Manager Form of Government - October 9, 1945 October 1945 City Manager: Jack Speer (Acting) October 1945 - March 1946 City Manager: George A. Hight March 1946 - April 1946 City Manager: E. Arthur Durham May 1946 - May 1947 City Manager: Roderick B. Thomas June 1947 - April 1949 City Manager: H. H. Allen April 1949 - September 1949 City Manager: Maurice W. Cochran (Resigned) September 1949 - October 1949 City Manager: R. W. McCamy (Acting) October 1949 - April 1953 City Manager: William B. Collier April 1953 - June 1953 City Manager: O. N. Stevens June 1953 - August 1958 City Manager: Russell E. McClure August 1958 - November 1958 City Manager: I. M. Singer (Acting) November 1958 - December 1967 City Manager: Herbert Whitney January 1968 - September 1981 City Manager: R. Marvin Townsend (Resigned) October 1981 - March 1982 City Manager: Ernest Briones (Acting) City of Corpus Christi Former City Managers Page 2 March 1982 - December 1985 City Manager: Edward Martin (Resigned) January 1986 - June 1986 City Manager: Ernest Briones (Acting) June 1986 - March 1988 City Manager: Craig McDowell (Terminated) March 1988 - June 1996 City Manager: Juan Garza June 1996 - October 1996 City Manager: Bill Hennings (Acting) October 1996 - July 1998 City Manager: Bill Hennings August 1998 - February 7, 2003 City Manager: David Garcia Februray 7, 2003 - April 15, 2003 City Manager: George “Skip” Noe (Acting) April 15, 2003 - September 2008 City Manager: George “Skip” Noe September 2008 - November 2008 City Manager: Ángel R. Escobar (Acting) November 2008 - March 5, 2011 City Manager: Ángel R. Escobar March 2011 - May 2011 City Manager: Margie C. -

Washington, Wednesday, April 29, 1953 TITLE 3—THE PRESIDENT

FEDERAL REGISTER 1934 VOLUME 18 \ NUMBER 82 ^ i f l V I T E O ^ Washington, Wednesday, April 2 9 , 1953 TITLE 3— THE PRESIDENT within the department or agency is CONTENTS clearly consistent with the interests of EXECUTIVE ORDER 10450 the national security. THE PRESIDENT S e c . 3. (a) The appointment of each Se c u r it y R equirements for Executive Order Pa®e civilian officer or employee in any depart G o v e r n m e n t E m p l o y m e n t Security requirements for Govem- ment or agency of the Government shall ernment employment__________ 2489 WHEREAS the interests of the na be made subject to investigation. The tional security require that all persons scope of the investigation shall be deter EXECUTIVE AGENCIES privileged to be employed in the depart mined in the first instance according to ments and agencies of the Government, the degree of adverse effect the occupant Agriculture Department shall be reliable, trustworthy, of good of the position sought to be filled could See Production and Marketing conduct and character, and of complete bring about, by virtue of the nature of Administration. and unswerving loyalty to the United the position, on the national security, but Air Force Department States; and in no event shall the investigation in Rules and regulations: WHEREAS the American tradition clude less than a national agency check Civilian personnel; security re that all persons should receive fair, im (including a check of the fingerprint files quirements for Government partial, and equitable treatment at the of the Federal -

Washington, Tuesday, April 28, 1953 TITLE 3—THE PRESIDENT CONTENTS

VOLUME 18 ' V , 1 9 3 4 c f P NUMBER 81 * On it io ^ Washington, Tuesday, April 28, 1953 TITLE 3— THE PRESIDENT States of America the one hundred and CONTENTS seventy-seventh. PROCLAMATION 30J2 D w ight D . Eisenhow er THE PRESIDENT World T rade W eek , 1953 By the President: Proclamation Page World Trade Week, 1953________ 2469 |BY THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES W alter B. S m ith , OF AMERICA Acting Secretary^of State. Executive Order Creation of emergency board to A PROCLAMATION [F. R. Doc. 53-3752; Filed, Apr. 24, 1953; 2:04 p. m.] investigate dispute between New WHEREAS it is the policy of this Gov York, Chicago & St. Louis Rail ernment to foster mutual understand- road Company and certain em ling and friendship among nations; and ployees____________ _________ 2469 WHEREAS world trade, freely con EXECUTIVE ORDER 10449 ducted by private enterprise, increases EXECUTIVE AGENCIES [material well-being and develops friendly Creating an E mergency B oard T o Inves (intercourse among free peoples; and tigate a D ispute B etween the N ew Agriculture Department WHEREAS international trade among Y ork, Chicago & S t . Louis R ail See Farm Credit Administration; [the nations of the free world adds to the road Company and Certain of I ts Farmers Home Administration; [economic strength upon which their Employees Production and Marketing Ad [common defense is based; and WHEREAS a dispute exists between ministration. WHEREAS increased international the New York, Chicago & St. Louis Rail Army Department [exchange of goods, services, and capital road Company, a carrier, and certain of See also Engineers Corps. -

U. S. Birth Statistics, January-April 1953

U. S. Birth Statistics, January-April 1953 Iln .April 1953 there were ain estimated 292,000 ord again in 1952 with an estimated 3,889,000 live births. This is the first time in about a live births. year that births were not hiigher than the cor- Based on registered births alone, 58,000 more responding monthly figure of the previous year. couples had a first child in 1951 than in 1950, The birth rate on an annual basis for this according to preliminary estimates. This 5- April-22.5 per 1,000 population-was also percent increase in first-born children was sonmewhat lower than a year ago. In 1952, largely a sequel to the marriage upswing that however, April births had been close to the all- began in June 1950, at the start of the Korean time record for this month. War. Births of second-born children increased For the first 4 months of 1953, the total num- ber of births remained high. During this Estimated total live births and registered live births, and birth rates in the United States, period, births occurred at an annual rate of 1940-52, and January-April 1952 and 1953 24.4 per 1,000 population, and totaled an esti- mated 1,262,000. This is 23,000, or 2 percent, [Data on total live births include estimates for unregis- tered births. Rates per 1,000 population] more than was estimated for the same period last year. These estimates allow for under- Estimated total Registered live registration of births. live births births Period Number Rate I Number Rate I OA c ,_~ ~1~ 0 0 4 Jan.-A pr. -

The Korean War

N ATIO N AL A RCHIVES R ECORDS R ELATI N G TO The Korean War R EFE R ENCE I NFO R MAT I ON P A P E R 1 0 3 COMPILED BY REBEccA L. COLLIER N ATIO N AL A rc HIVES A N D R E C O R DS A DMI N IST R ATIO N W ASHI N GTO N , D C 2 0 0 3 N AT I ONAL A R CH I VES R ECO R DS R ELAT I NG TO The Korean War COMPILED BY REBEccA L. COLLIER R EFE R ENCE I NFO R MAT I ON P A P E R 103 N ATIO N AL A rc HIVES A N D R E C O R DS A DMI N IST R ATIO N W ASHI N GTO N , D C 2 0 0 3 United States. National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives records relating to the Korean War / compiled by Rebecca L. Collier.—Washington, DC : National Archives and Records Administration, 2003. p. ; 23 cm.—(Reference information paper ; 103) 1. United States. National Archives and Records Administration.—Catalogs. 2. Korean War, 1950-1953 — United States —Archival resources. I. Collier, Rebecca L. II. Title. COVER: ’‘Men of the 19th Infantry Regiment work their way over the snowy mountains about 10 miles north of Seoul, Korea, attempting to locate the enemy lines and positions, 01/03/1951.” (111-SC-355544) REFERENCE INFORMATION PAPER 103: NATIONAL ARCHIVES RECORDS RELATING TO THE KOREAN WAR Contents Preface ......................................................................................xi Part I INTRODUCTION SCOPE OF THE PAPER ........................................................................................................................1 OVERVIEW OF THE ISSUES .................................................................................................................1 -

Index to Proceedings of the Economic and Social Council, 1953 (15Th Session)

.. INDEX TO PROCEEDINGS OF THE .. ECONOMIC AND. SOCIAL INDEX TO PROCEEDINGSCOUNCIL OF THE Fifteenth Session ECONOMIC AND.31 SOCIALMarch to 28 April. 1953 COUNCIL Fifteenth Session 31 March to 28 April. 1953 United Nations Headquarters Library Bibliographical Series No. E.6 United Nations HeadquartersUNITEDLibrary NATIONS New York Bibliographical Series No. E.6 ,~. 1953 UNITED NATIONS New York 1953 . \, ... - y , ~, ~.'• , c'" . , .'" .. .' .. .' \ . '. , .-, ~ ~ ,~ ~'" ~'.. ~ ~ ..c~' ~ • "4 " '4 TO" • , ... _ _ .. ,• •• • "." ' • • • .. \. '" ,.... , . STST/LIB/SER.B/E.6/LIB/SER.B/E.6 TheThe followingfollowing additionaladditional issuesissues inin thisthis seriesseries areare available:available: STST/LIB/SER.B/1./LIB/SER.B/1. SelectedSelected BibliographyBibliography ofof thethe SpecializecSpecializec AgenciesAgencies relatedrelated toto thethe UnitedUnited Nations.Nations. 1949.1949. (Sales(Sales No.No. 1949.1.16)1949.1.16) $0.25$0.25 STST/LIB/SER.B/2./LIB/SER.B/2. LatinLatin America,America, 1939-1949.1939-1949. AA SelectedSelected Bibliography.Bibliography. 1952.1952. (Sales(Sales No.No. 1952.1.12)1952.1.12) $1.50$1.50 ST/LIB/SER.B/E.6/LIB/SER.B/E.6 June 1953 .. United NationsNations PublicationPublication SalesSales No.:No.: 1953.1953.1.I. 2323 ..... Price:Price: $U.S.SU.S. 0.30;0.30; 2/-stg.;2/-stg.;Sw.Sw. fr.fr. 1.201.20 (or(orequivalentequivalentininotherothercurrencies)currencies) I • .. • .' • • ~ 'd .4" _. ~ Q ';) -'" .... """ '~ . -. .' " .:'. -...... ...,.. ..,. • '. '" ". ,""" ..•.• .',.' •• ,'. '.. n.· .. •... ,/...... -

Jan 7, 1955 U

~ ~ JOHN E. HUEY SERVICE OFFICER VETERANS COUNTY-CITY SERVICE OFFICE COUNTY OF NUECES - CITY OF CORPUS CHRISTI TELEPHONE 3-8407 -:- 1811 SHORELINE BLVD. P. 0. BOX 764 CORPUS CHRISTI, TEXAS Jan 7, 1955 u.. REYNA. ADOLFO de Jesus, Jr. 10 C S Dr. Hector P. Garcia, M. D. 3024 Morgan St. Corpus Christi,Tex. Dear Br. Garcia: Attached is a 3-page letter from the Army addressed to Sen. Lyndon B. Johnson in connection with the above-captioned veteran's case. You contacted the Senator direct and we feel that you would be die to better explain the case to the mother from a medical standpoint being a doctor, than we could. On the basis of the letter and the fact that he is in receipt of 100% disability compensation from the V.A., I frankly do not believe that any further action should be instituted at this time. Under the circumstances, we believe that the veteran should return the Gepeval_pischarge which he has in his-2-0ssession so that t~ie authorities can replace same with an Honorable discharze under the regulations as set forth in the marked paragraph of the letter, which is considerably better than the General Discharge. Please return the enclosure for our files after it has served~its purpose, and thank you. \ Sincerely, R'ildhn04 E.' Huey 5-9 b/Veterans Service Officer JEH:dbb CC-mother .. DEPARTMENT OF THE ARM OFFICE OF THE CHIEF OF LEGISLATIVE LIAISON WASHINGTON 25, D. C. In reply refer to: 28 December 1954 201 Reyna, Jr., Adolfo de Jesus uS 54 116 379 (29 Oct 54) Honorable Lyndon B. -

Pulp Magazines Ace-High Magazine, New York: Readers’ Publishing Corp., New York: Clayton Magazines, New York: Dell Publishing 677 1 December 18, 1922, Vol

Shirley Papers 391 Published Materials Box Folder Folder Title Published Materials Pulp Magazines Ace-High Magazine, New York: Readers’ Publishing Corp., New York: Clayton Magazines, New York: Dell Publishing 677 1 December 18, 1922, Vol. 8, no. 4 2 July 3, 1923, Vol. 12, no. 1 3 March 3, 1924, Vol. 16, no. 1 4 May 3, 1924, Vol. 17, no. 1 5 May 18, 1924, Vol. 17, no. 2 6 March 3, 1925, Vol. 22, no. 1 7 May 18, 1925, Vol. 13[sic], no. 2 8 December 18, 1925, Vol. 26, no. 4 9 February 18, 1926, Vol. 27, no. 4 10 October 3, 1926, Vol. 31, no. 3 678 1 January, 1927, Vol. 40, no. 1 2 February, 1927, Vol. 40, no. 3 3 June 18, 1927, Vol. 36[sic], no. 4 4 August 3, 1927, Vol. 37[sic], no. 3 5 September 18, 1927, Vol. 38[sic], no. 2 6 December, 1927, Vol. 39[sic], no. 3 7 December, 1927, Vol. 39[sic], no. 4 8 April, 1928, Vol. 41, no. 4 9 June, 1928, Vol. 42, no. 3 679 1 July, 1928, Vol. 43, no. 1 2 August, 1928, Vol. 43, no. 3 3 August, 1928, Vol. 43, no. 4 4 September, 1928, Vol. 44, no. 2 5 October, 1928, Vol. 44, no. 4 6 February, 1929, Vol. 46, no. 4 7 June, 1929, Vol. 48, no. 4 8 August, 1929, Vol. 49, no. 4 9 September, 1929, Vol. 50, no. 1 680 1 September, 1929, Vol. 50, no. 2 680 2 October, 1929, Vol. -

Peryscope April 1953

flll~: ~~···· ~?-1~:::· :·:t: 7. ··::~ I•t . • J Se::,:·z· • • As 'f;~}.~ ~!Y..$§ By JAMES G. SHEA, Manager of Public Relations APRIL 1953 A weakness of the vast freeway construction program in Southern California is the failure to provide motor coach turnouts at important points as these freeways are built. This serious oversight is preventing full use of the freeways, thereby denying advantages to transit patrons and motor ists alike. The entire public is_ entitled to the improved mass transportation which will follow if freeways are designed for full utility. Whatever your means of transporta tion, you can help to overcome this short A~EYOU coming of the highway SURE building program and PooCH IE serve your own best DlDN'T interest by calling the ~EAR problem and its simple us SAY solution to the atten ~;:;;::::;;;;:;::{ '006 5\-IOW~ tion of your state legislators. In many localities transit cannot offer attractive service via freeways unless there are places to load and discharge passengers. Already several com munities have come to realize that although they have beautiful new expressways they actually have less public transportation because there is no way for transit to operate satisfactory service without turnouts. To assure maximum use of these traffic arteries the state law regarding freeways should require that turnouts be included in the general program where s,uch facilities are in the public interest. OSANTA AWA VALLEY 0 The ultimate function of freeways is to move the maximum number of people, and bus operation •006 S~OW• over freeways will help to achieve this objective API<.lL26 while at the same time helping to reduce the total LAPALM~ PARK•ANAHEIM traffic volume. -

Appointment Schedules Series

DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER LIBRARY ABILENE, KANSAS WHITE HOUSE OFFICE, OFFICE OF THE STAFF SECRETARY: Records of Paul T. Carroll, Andrew J. Goodpaster, L. Arthur Minnich and Christopher H. Russell, 1952-61 Appointment Schedules Series CONTAINER LIST Box No. Contents 1 Appointment Schedule January thru April 1953 (1) [January 2 - February 11, 1953] Appointment Schedule January thru April 1953 (2) [February 12 - March 4, 1953] Appointment Schedule January thru April 1953 (3) [March 5-24, 1953] Appointment Schedule January thru April 1953 (4) [March 25 - April 10, 1953] Appointment Schedule January thru April 1953 (5) [April 11-30, 1953] Appointment Schedule May thru August 1953 (1) [May 1-22, 1953] Appointment Schedule May thru August 1953 (2) [May 23 – June 16, 1953] Appointment Schedule May thru August 1953 (3) [June 17-30, 1953] Appointment Schedule May thru August 1953 (4) [July 1-21, 1953] Appointment Schedule May thru August 1953 (5) [July 22 – August 6, 1953] Appointment Schedule May thru August 1953 (6) [August 7-31, 1953] Appointment Schedule September thru December 1953 (1) [September 1-30, 1953] Appointment Schedule September thru December 1953 (2) [October 1-22, 1953] Appointment Schedule September thru December 1953 (3) [October 23 – November 14, 1953] Appointment Schedule September thru December 1953 (4) [November 15 – December 12, 1953] Appointment Schedule September thru December 1953 (5) [December 13-30, 1953] Appointment Schedule January thru April 1954 (1) [January 1-31, 1954] Appointment Schedule January thru April 1954 (2)