Roots of Shotokan: Funakoshi's Original 15 Kata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

©Northern Karate Schools 2017

©Northern Karate Schools 2017 NORTHERN KARATE SCHOOLS MASTERS GUIDE – CONTENTS Overview Essay: Four Black Belt Levels and the Title “Sensei” (Hanshi Cezar Borkowski, Founder, Northern Karate Schools) Book Excerpt: History and Traditions of Okinawan Martial Arts (Master Hokama Tetsuhiro) Essay: What is Kata (Kyoshi Michael Walsh) Northern Karate Schools’ Black Belt Kata Requirements Northern Karate Schools’ Kamisa (Martial Family Tree) Article: The Evolution of Ryu Kyu Kobudo (Hanshi Cezar Borkowski, ed. Kyoshi Marion Manzo) Northern Karate Schools’ Black Belt Kobudo Requirements Northern Karate Schools’ Additional Black Belt Requirements ©Northern Karate Schools 2017 NORTHERN KARATE SCHOOLS’ MASTERS CLUB - OVERVIEW In response to unprecedented demand and high retention rates among senior students, Northern Karate Schools Masters Club, an advanced, evolving program, was launched in 1993 by Hanshi Borkowski. Your enrolment in this unique program is a testament to your continued commitment to achieving Black Belt excellence and your devotion to realising personal best through martial arts study. This Masters Club Student Guide details requirements for Shodan to Rokudan students. It contains select articles, essays and book excerpts as well as other information aimed at broadening your understanding of the history, culture and philosophy of the martial arts. Tradition is not to preserve the ashes but to pass on the flame. Gustav Mahler ©Northern Karate Schools 2017 FOUR BLACK BELT LEVELS AND THE TITLE “SENSEI” by Hanshi Cezar Borkowski Karate students and instructors often confuse the terms Black Belt and Sensei. Sensei is commonly used to mean teacher however, the literal translation of the word is one who has gone before. Quite simply, that means an instructor who has experienced certain things and shares what he/she has learned with others - a tour guide along the road of martial arts life. -

Ash's Okinawan Karate

ASH’S OKINAWAN KARATE LOCATION: 610 Professional Drive, Suite 1, Bozeman, Montana 59718 PHONE: 406-994-9194 EMAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: www.ashsokinawankarate.com INSTRUCTORS: Brian Ash – Roku dan (6th degree Black Belt) Lisa Ash – Yon dan (4th degree Black Belt) Kaitlyn Ash – San dan (3rd degree Black Belt) Karate is an individual endeavor. Each person is taught and advanced according to his/her own ability. Initially, you will learn a basic foundation of karate techniques on which to build. Fundamentals of actual street and sport karate are later incorporated into your training as well as the Isshinryu kata. All classes include stretching and calisthenics. To be effective in karate, you must be in optimum shape. This book lists the minimal testing criteria for each belt level. Your sensei will decide when you are ready for testing, even if you have met the listed criteria. The rank criteria are simply a guide for the student. Practice is very important to prepare yourself for learning and advancement. To be a true black belt, you must not rush through the kyu ranks. Take advantage of that time to practice and improve all techniques and kata. We can never stop learning or improving ourselves. The secret of martial arts success is practice. Like uniforms are required during class representing tradition and equality in students. The main objective of Isshinryu is the perfection of oneself through both physical and mental development. Ash’s Karate combines teaching Isshinryu karate with a well- rounded exercise program. MISSION STATEMENT: To instill confidence, courtesy, and respect while building mental and physical strength, self discipline, balance, focus, endurance and perseverance in students so that they may empower themselves to overcome physical and mental obstacles, build character and unify mind, body and spirit. -

The Folk Dances of Shotokan by Rob Redmond

The Folk Dances of Shotokan by Rob Redmond Kevin Hawley 385 Ramsey Road Yardley, PA 19067 United States Copyright 2006 Rob Redmond. All Rights Reserved. No part of this may be reproduced for for any purpose, commercial or non-profit, without the express, written permission of the author. Listed with the US Library of Congress US Copyright Office Registration #TXu-1-167-868 Published by digital means by Rob Redmond PO BOX 41 Holly Springs, GA 30142 Second Edition, 2006 2 Kevin Hawley 385 Ramsey Road Yardley, PA 19067 United States In Gratitude The Karate Widow, my beautiful and apparently endlessly patient wife – Lorna. Thanks, Kevin Hawley, for saying, “You’re a writer, so write!” Thanks to the man who opened my eyes to Karate other than Shotokan – Rob Alvelais. Thanks to the wise man who named me 24 Fighting Chickens and listens to me complain – Gerald Bush. Thanks to my training buddy – Bob Greico. Thanks to John Cheetham, for publishing my articles in Shotokan Karate Magazine. Thanks to Mark Groenewold, for support, encouragement, and for taking the forums off my hands. And also thanks to the original Secret Order of the ^v^, without whom this content would never have been compiled: Roberto A. Alvelais, Gerald H. Bush IV, Malcolm Diamond, Lester Ingber, Shawn Jefferson, Peter C. Jensen, Jon Keeling, Michael Lamertz, Sorin Lemnariu, Scott Lippacher, Roshan Mamarvar, David Manise, Rolland Mueller, Chris Parsons, Elmar Schmeisser, Steven K. Shapiro, Bradley Webb, George Weller, and George Winter. And thanks to the fans of 24FC who’ve been reading my work all of these years and for some reason keep coming back. -

World Karate Federation

WORLD KARATE FEDERATION Version 6 Amended July 2009 VERSION 6 KOI A MENDED J ULY 2009 CONTENTS KUMITE RULES............................................................................................................................ 3 ARTICLE 1: KUMITE COMPETITION AREA............................................................................... 3 ARTICLE 2: OFFICIAL DRESS .................................................................................................... 4 ARTICLE 3: ORGANISATION OF KUMITE COMPETITIONS ...................................................... 6 ARTICLE 4: THE REFEREE PANEL ............................................................................................. 7 ARTICLE 5: DURATION OF BOUT ............................................................................................ 8 ARTICLE 6: SCORING ............................................................................................................... 8 ARTICLE 7: CRITERIA FOR DECISION..................................................................................... 12 ARTICLE 8: PROHIBITED BEHAVIOUR ................................................................................... 13 ARTICLE 9: PENALTIES........................................................................................................... 16 ARTICLE 10: INJURIES AND ACCIDENTS IN COMPETITION ................................................ 18 ARTICLE 11: OFFICIAL PROTEST ......................................................................................... 19 ARTICLE -

Bassai Sampler

Black Belt Study Group Masters Series Bassai This Book The purpose of this document is to remind practitioners of the Bassai kata and how to get the best from them. No publication can teach a kata and its applications; this can only be done by a qualified instructor in a time set aside for tuition. This document can help to jog the memory and provide inspi- ration for further study of one of the greatest exercises in ka- rate. The Bassai kata is one of the most prevalent in martial arts. It occurs in many different styles with only slight differences. This in itself shows a common root to the traditions which share Bassai. Known variously as Patsai, Passai, Bassai Dai, or other variations, this kata can be seen in Taekwondo, Shito Ryu, Goju Ryu, Kyokushinkai, Wado Ryu, and many other styles of karate. Different Sokes have placed the emphasis on different techniques, but truthfully, they are all Bassai. The version shown within heralds from Shotokan, nominally the style of Funakoshi Gichin, credited by many as the father of modern karate-do. Certainly, many movements within Shotokan have become homogenised and made safe for practice by school children. This does not mean that the old, dangerous techniques are removed, just that their applications have merely been overlooked in favour of simplistic explanations and hidden in order to favour the aesthetic required for competition. The writing shown here is the Kanji for Bassai Dai. Originally it would have been written differently, but Funakoshi chose to write it in Japanese (which was a foreign language to him). -

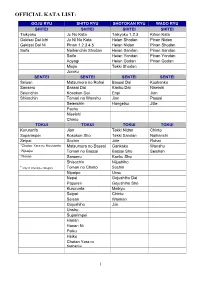

Official Kata List

OFFICIAL KATA LIST: GOJU RYU SHITO RYU SHOTOKAN RYU WADO RYU SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI Taikyoku Ju No Kata Taikyoku 1.2.3 Kihon Kata Gekisai Dai Ichi Ju Ni No Kata Heian Shodan Pinan Nidan Gekisai Dai Ni Pinan 1.2.3.4.5 Heian Nidan Pinan Shodan Saifa Naihanchin Shodan Heian Sandan Pinan Sandan Saifa Heian Yondan Pinan Yondan Aoyagi Heian Godan Pinan Godan Miojio Tekki Shodan Juroku SENTEI SENTEI SENTEI SENTEI Seisan Matsumora no Rohai Bassai Dai Kushanku Sanseru Bassai Dai Kanku Dai Niseishi Seiunchin Kosokun Dai Enpi Jion Shisochin Tomari no Wanshu Jion Passai Seienchin Hangetsu Jitte Pachu Niseishi Chinto TOKUI TOKUI TOKUI TOKUI Kururunfa Jion Tekki Nidan Chinto Suparimpei Kosokun Sho Tekki Sandan Naihanchi Seipai Sochin Jitte Rohai *Chatan Yara no Kushanku Matsumura no Bassai Gankaku Wanshu *Nipaipo Tomari no Bassai Bassai Sho Seishan *Hanan Sanseru Kanku Sho Shisochin Nijushiho * only in interstyle category Tomari no Chinto Sochin Nipaipo Unsu Nepai Gojushiho Dai Papuren Gojushiho Sho Kururunfa Meikyo Seipai Chinte Seisan Wankan Gojushiho Jiin Unshu Suparimpei Hanan Hanan Ni Paiku Heiku Chatan Yara no Kushanku 1 OFFICIAL LIST OF SOME RENGOKAI STYLES: GOJU SHORIN RYU SHORIN RYU UECHI RYU USA KYUDOKAN OKINAWA TE SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI Taikyoku Jodan Fukiu Gata Ichi Fugyu Shodan Kanshiva Taikyoku Chiudan Fukiu Gata Ni Fugyu Nidan Kanshu Taikyoku Gedan Pinan Nidan Pinan Nidan Sechin Taikyoku Consolidale Ichi Pinan Shodan Pinan Shodan Seryu Taikyoku Consolidale Ni Pinan Sandan Pinan Sandan SENTEI Taikyoku Consolidale San Pinan -

The Naihanchi Enigma by Tim Shaw Web Version At

The Naihanchi Enigma by Tim Shaw Web version at: http://www.wadoryu.org.uk/naihanchi.html Introduction Naihanchi kata within Wado Ryu Within the Wado Ryu style of Japanese karate the kata Naihanchi holds a special place, positioned as it is as a gateway to the complexities of Seishan and Chinto. But as a gateway it presents its own mysteries and contradictions. Through Naihanchi Wado stylists are directed to study the subtleties of body movements and develop particular ways of generating energy found primarily in this kata. They are taught that the essence of this ancient Form is to be found in the stance and that the inherent principles are applied directly to the Wado Ryu Kumite (the pairs exercises) and to achieve a stage where these principles become part of the practitioners body and natural movements involves countless repetitions of this particular form. The following tantalizing quote from the founder of Wado Ryu Karate Hironori Ohtsuka, gives intriguing clues as to the value and influence that this particular kata holds. "Every technique (in Naihanchi) has its own purpose. I personally favour Naihanchi. It is not interesting to the eye, but it is extremely difficult to use. Naihanchi increases in difficulty with more time spent practicing it, however, there is something "deep" about it. It is fundamental to any move that requires reaction. Some people may call me foolish for my belief. However, I prefer this kata over all else and hence incorporate it into my movement."1 Many Wado karate-ka practice Naihanchi diligently, while remaining largely unaware of the background and long history of this unusual kata. -

Personal Development Student Guide

‘ 北剛柔空⼿道 Karate Studio of Utica Personal Development Student Guide UticaKarate.com Karate Studio of Utica Chief Instructor Profile Kyoshi Shihan Efren Reyes Has well over 30 years of experience practicing and teaching martial arts. He began his Karate training at age 19. No stranger to combative arts since he was already experienced in boxing at the time he was introduced to karate by his older brother. He has groomed and continues to mentor many of our blackbelts both near and far. He holds Kyoshi level certification in Goju-Ryu Karate under the late Sensei Urban and Sensei Van Cliff as well as a 3rd Dan in Aikijutsu under Sensei Van Cliff who has also ranked him master level in Chinese Goju-Ryu. Sensei Urban acknowledged Shihan has the mastery and expertise to be recognized as grand master of his own style of Goju-Ryu since he development of Goju-Ryu had evolved to point of growing his own vision and practice of karate unique to Shihan. This is what is practiced and taught at the Utica Karate. He has also studied Wing Chun in later years to further his understanding and perspective of techniques in close quarters. Shihan has promoted Karate-do through his style of Goju-Ryu under North American Goju karate. Shihan has directed many classes and seminars on various subjects’ ranging from basic self defense to meditation. Karate Studio of Utica Black Belt Instructor Profiles Sensei Philip Rosa Mr. Rosa holds the rank of Sensei (5th degree) and has been practicing Goju-Ryu Karate under Shihan Reyes since 1990. -

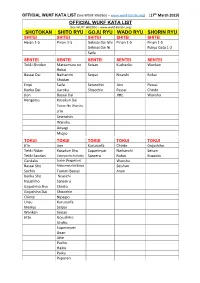

Official Wukf Kata List Shotokan Shito Ryu Goju

OFFICIAL WUKF KATA LIST (See WUKF WebSite – www.wukf-Karate.org) [17th March 2019] OFFICIAL WUKF KATA LIST (See WUKF WebSite – www.wukf-Karate.org) SHOTOKAN SHITO RYU GOJU RYU WADO RYU SHORIN RYU SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI Heian 1-5 Pinan 1-5 Gekisai Dai Ichi Pinan 1-5 Pinan 1-5 Gekisai Dai Ni Fukyu Gata 1-2 Saifa SENTEI SENTEI SENTEI SENTEI SENTEI Tekki Shodan Matsumura no Seisan Kushanku Wankan Rohai Bassai Dai Naihanchi Seipai Niseishi Rohai Shodan Empi Saifa Seiunchin Jion Passai Kanku Dai Jiuroku Shisochin Passai Chinto Jion Bassai Dai Jitte Wanshu Hangetsu Kosokun Dai Tomari No Wanshu Ji'in Seienchin Wanshu Aoyagi Miojio TOKUI TOKUI TOKUI TOKUI TOKUI Ji'in Jion Kururunfa Chinto Gojushiho Tekki Nidan Kosokun Sho Suparimpai Naihanchi Seisan Tekki Sandan Ciatanyara No Kushanku Sanseru Rohai Kusanku Gankaku Sochin (Aragaki ha) Wanshu Bassai Sho Matsumura No Bassai Seishan Sochin Tomari Bassai Anan Kanku Sho Niseichi Nijushiho Sanseiru Gojushiho Sho Chinto Gojushiho Dai Shisochin Chinte Nipaipo Unsu Kururunfa Meikyo Seipai Wankan Seisan Jitte Gojushiho Unshu Suparimpei Anan Jitte Pacho Haiku Paiku Papuren KATA LIST - WUKF COMPETITION UECHI RYU KYOKUSHINKAI BUDOKAN GOSOKU RYU SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI Kanshiva Pinan 1-5 Heian 1-5 Kihon Ichi No Kata Sechin Kihon Yon No Kata Kanshu Kime Ni No Kata Seiryu (Kiyohide) Ryu No Kata Uke No Kata SENTEI SENTEI SENTEI SENTEI Sesan Geksai Dai Empi Ni No Kata Kanchin Tsuki No Kata Tekki 1-2 Kime No Kata Sanseryu Yantsu Bassai Dai Gosoku Tensho Kanku Dai Gosoku Yondan Saifa Jion Sanchin no -

The Shorin-Ryu Shorinkan of Williamsburg

Shorin-Ryu of Williamsburg The Shorin-Ryu Karate of Williamsburg Official Student Handbook Student Name: _________________________________________ Do not duplicate 1 Shorin-Ryu of Williamsburg General Information We are glad that you have chosen our school to begin your or your child’s journey in the martial arts. This handbook contains very important information regarding the guidelines and procedures of our school to better inform you of expectations and procedures regarding training. The quality of instruction and the training at our dojo are of the highest reputation and are designed to bring the best out of our students. We teach a code of personal and work ethics that produce citizens of strong physical ability but most importantly of high character. Students are expected to train with the utmost seriousness and always give their maximum physical effort when executing techniques in class. Instructors are always observing and evaluating our students based on their physical improvements but most of all, their development of respect, courtesy and discipline. Practicing karate is very similar to taking music lessons- there are no short cuts. As in music, there are people that possess natural ability and others that have to work harder to reach goals. There are no guarantees in music instruction that say someone will become a professional musician as in karate there are no guarantees that a student will achieve a certain belt. This will fall only on the student and whether they dedicate themselves to the instruction given to them. Our school does not offer quick paths to belts for a price as many commercial schools do. -

Yu Gup Ja Training Manual

Independent Tang Soo Do Association YU GUP JA TRAINING MANUAL © Copyright South Hills Karate Academy (Gene Garbowsky) No part of this document may be reproduced, copied or distributed without express permission from Master Gene Garbowsky Published May, 2013 A Message from Sa Bom Nim Gene Garbowsky, Kwan Jang Nim, Independent Tang Soo Do Association As a member of the Independent Tang Soo Do Association, I hope that you will come to re- alize the benefits of training in Tang Soo Do. As you may know, I have been teaching this Martial Art to hundreds of students over the past 30 years. I truly believe that every man, women, and child can benefit in many ways from practicing Martial Arts and Tang Soo Do. What are Martial Arts? It is the name given to the traditional systems of self-defense that have been practiced in Eastern and Western societies for thousands of years. Masters of the ancient Martial Arts ultimately discovered that mastery of the body comes through mas- tery of the mind. Therefore, the practice of Martial Arts is a way to a more fulfilling life. It is a path to freedom from self-confinement and the ultimate goal to mental and physical har- mony. Martial Arts training can absolutely change a person physically, psychologically, and emo- tionally in a very positive way. Regular physi- cal activity energizes the body, and since martial arts are based on natural law, the body can quickly reach top conditioning. Once physical changes develop, they soon lead to the mental and emotional improve- ments that many seek through the martial arts. -

Karate Rank Requirements

Karate Rank Requirements YOUTH RANK: KYUKYU - 9TH KYU (1 YELLOW TAG) (5-7 year olds) HAKKYU - 8TH KYU (2 YELLOW TAGS) YOUTH & ADULT RANKS NANAKYU - 7TH KYU (YELLOW BELT) ROKKYU - 6TH KYU (GREEN TAG) GOKYU - 5TH KYU (GREEN BELT) YONKYU - 4TH KYU (GREEN BELT / RED TAG) SANKYU - 3RD KYU (BROWN BELT) NIKYU - 2ND KYU IKKYU - 1ST KYU SHODAN 1 / 21 Karate Rank Requirements NIDAN SANDAN YONDAN YOUTH - KYUKYU - 9TH KYU (YELLOW TAG) (5-7 yr. olds) HOJO UNDO SHORIN KATA Punching None Blocks Front Kick Three Basic Stances: Front Stance Cat Stance Horse Stance YOUTH - HAKKYU - 8TH KYU (2 YELLOW TAGS) HOJO UNDO SHORIN KATA Punching Drill None Blocking Drill 2 / 21 Karate Rank Requirements Front Kick Three Basic Stances: Front Stance Cat Stance Horse Stance NANAKYU - 7TH KYU (YELLOW BELT) HOJO UNDO SHORIN KATA SHUDOKAN KATA Punching Drill None Taikyoku Shodan Blocking Drill Front Kick Three Basic Stances Front Stance Cat Stance Horse Stance IPPON KUMITE (ONE PERSON) Upper Series - Upper block-punch - Circle block-punch - Cross block-punch 3 / 21 Karate Rank Requirements Middle Series - Outer block-punch - Circle block-punch - Cross block-punch Lower Series - Lower block-punch OTHER TWO PERSON MATERIAL - Arm conditioning ROKKYU - 6TH KYU (YELLOW BELT /GREEN TAG) HOJO UNDO SHORIN KATA SHUDOKAN KATA Kyan Lines 1-3 None Taikyokyu Nidan Taikyokyu Sandan 4 / 21 Karate Rank Requirements IPPON KUMITE (ONE PERSON) Upper Series - Upper block-punch - Circle block-punch - Cross block-punch Middle Series - Outer block-punch - Circle block-punch - Cross block-punch