Bassai Sampler

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Folk Dances of Shotokan by Rob Redmond

The Folk Dances of Shotokan by Rob Redmond Kevin Hawley 385 Ramsey Road Yardley, PA 19067 United States Copyright 2006 Rob Redmond. All Rights Reserved. No part of this may be reproduced for for any purpose, commercial or non-profit, without the express, written permission of the author. Listed with the US Library of Congress US Copyright Office Registration #TXu-1-167-868 Published by digital means by Rob Redmond PO BOX 41 Holly Springs, GA 30142 Second Edition, 2006 2 Kevin Hawley 385 Ramsey Road Yardley, PA 19067 United States In Gratitude The Karate Widow, my beautiful and apparently endlessly patient wife – Lorna. Thanks, Kevin Hawley, for saying, “You’re a writer, so write!” Thanks to the man who opened my eyes to Karate other than Shotokan – Rob Alvelais. Thanks to the wise man who named me 24 Fighting Chickens and listens to me complain – Gerald Bush. Thanks to my training buddy – Bob Greico. Thanks to John Cheetham, for publishing my articles in Shotokan Karate Magazine. Thanks to Mark Groenewold, for support, encouragement, and for taking the forums off my hands. And also thanks to the original Secret Order of the ^v^, without whom this content would never have been compiled: Roberto A. Alvelais, Gerald H. Bush IV, Malcolm Diamond, Lester Ingber, Shawn Jefferson, Peter C. Jensen, Jon Keeling, Michael Lamertz, Sorin Lemnariu, Scott Lippacher, Roshan Mamarvar, David Manise, Rolland Mueller, Chris Parsons, Elmar Schmeisser, Steven K. Shapiro, Bradley Webb, George Weller, and George Winter. And thanks to the fans of 24FC who’ve been reading my work all of these years and for some reason keep coming back. -

Roots of Shotokan: Funakoshi's Original 15 Kata

Joe Swift About The Author: Joe Swift, native of New York State (USA) has lived in Japan since 1994. He holds a dan-rank in Isshinryu Karatedo, and also currently acts as assistant instructor (3rd dan) at the Mushinkan Shoreiryu Karate Kobudo Dojo in Kanazawa, Japan. He is also a member of the International Ryukyu Karate Research Society and the Okinawa Isshinryu Karate Kobudo Association. He currently works as a translator/interpreter for the Ishikawa International Cooperation Research Centre in Kanazawa. He is also a Contributing Editor for FightingArts.com. Roots Of Shotokan: Funakoshi's Original 15 Kata Part 1- Classification & Knowledge Of Kata Introduction Gichin Funakoshi is probably the best known karate master of the early 20th century and is known by many as the "Father Of Japanese Karate." It was Funakoshi who was first selected to demonstrate his Okinawan art on mainland Japan. In Japan Funakoshi helped build the popularity of his fledgling art and helped it gain acceptance by the all important Japanese organization founded (and sanctioned by the government) to preserve and promote the martial arts and ways in Japan (the Dai Nippon Butokukai). An author of several pioneering books on karate, he was the founder Shotokan karate from which many other styles derived. When Funakoshi arrived in Japan in 1922, he originally taught a total of fifteen kata, although it has been speculated that he probably knew many more. The purpose of this article will be to introduce some of the theories on the possible origins of these kata, provide some historical testimony on them, and try and improve the overall understanding of the roots of Shotokan. -

World Karate Federation

WORLD KARATE FEDERATION Version 6 Amended July 2009 VERSION 6 KOI A MENDED J ULY 2009 CONTENTS KUMITE RULES............................................................................................................................ 3 ARTICLE 1: KUMITE COMPETITION AREA............................................................................... 3 ARTICLE 2: OFFICIAL DRESS .................................................................................................... 4 ARTICLE 3: ORGANISATION OF KUMITE COMPETITIONS ...................................................... 6 ARTICLE 4: THE REFEREE PANEL ............................................................................................. 7 ARTICLE 5: DURATION OF BOUT ............................................................................................ 8 ARTICLE 6: SCORING ............................................................................................................... 8 ARTICLE 7: CRITERIA FOR DECISION..................................................................................... 12 ARTICLE 8: PROHIBITED BEHAVIOUR ................................................................................... 13 ARTICLE 9: PENALTIES........................................................................................................... 16 ARTICLE 10: INJURIES AND ACCIDENTS IN COMPETITION ................................................ 18 ARTICLE 11: OFFICIAL PROTEST ......................................................................................... 19 ARTICLE -

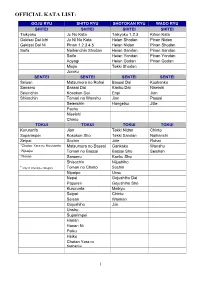

Official Kata List

OFFICIAL KATA LIST: GOJU RYU SHITO RYU SHOTOKAN RYU WADO RYU SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI Taikyoku Ju No Kata Taikyoku 1.2.3 Kihon Kata Gekisai Dai Ichi Ju Ni No Kata Heian Shodan Pinan Nidan Gekisai Dai Ni Pinan 1.2.3.4.5 Heian Nidan Pinan Shodan Saifa Naihanchin Shodan Heian Sandan Pinan Sandan Saifa Heian Yondan Pinan Yondan Aoyagi Heian Godan Pinan Godan Miojio Tekki Shodan Juroku SENTEI SENTEI SENTEI SENTEI Seisan Matsumora no Rohai Bassai Dai Kushanku Sanseru Bassai Dai Kanku Dai Niseishi Seiunchin Kosokun Dai Enpi Jion Shisochin Tomari no Wanshu Jion Passai Seienchin Hangetsu Jitte Pachu Niseishi Chinto TOKUI TOKUI TOKUI TOKUI Kururunfa Jion Tekki Nidan Chinto Suparimpei Kosokun Sho Tekki Sandan Naihanchi Seipai Sochin Jitte Rohai *Chatan Yara no Kushanku Matsumura no Bassai Gankaku Wanshu *Nipaipo Tomari no Bassai Bassai Sho Seishan *Hanan Sanseru Kanku Sho Shisochin Nijushiho * only in interstyle category Tomari no Chinto Sochin Nipaipo Unsu Nepai Gojushiho Dai Papuren Gojushiho Sho Kururunfa Meikyo Seipai Chinte Seisan Wankan Gojushiho Jiin Unshu Suparimpei Hanan Hanan Ni Paiku Heiku Chatan Yara no Kushanku 1 OFFICIAL LIST OF SOME RENGOKAI STYLES: GOJU SHORIN RYU SHORIN RYU UECHI RYU USA KYUDOKAN OKINAWA TE SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI Taikyoku Jodan Fukiu Gata Ichi Fugyu Shodan Kanshiva Taikyoku Chiudan Fukiu Gata Ni Fugyu Nidan Kanshu Taikyoku Gedan Pinan Nidan Pinan Nidan Sechin Taikyoku Consolidale Ichi Pinan Shodan Pinan Shodan Seryu Taikyoku Consolidale Ni Pinan Sandan Pinan Sandan SENTEI Taikyoku Consolidale San Pinan -

The Naihanchi Enigma by Tim Shaw Web Version At

The Naihanchi Enigma by Tim Shaw Web version at: http://www.wadoryu.org.uk/naihanchi.html Introduction Naihanchi kata within Wado Ryu Within the Wado Ryu style of Japanese karate the kata Naihanchi holds a special place, positioned as it is as a gateway to the complexities of Seishan and Chinto. But as a gateway it presents its own mysteries and contradictions. Through Naihanchi Wado stylists are directed to study the subtleties of body movements and develop particular ways of generating energy found primarily in this kata. They are taught that the essence of this ancient Form is to be found in the stance and that the inherent principles are applied directly to the Wado Ryu Kumite (the pairs exercises) and to achieve a stage where these principles become part of the practitioners body and natural movements involves countless repetitions of this particular form. The following tantalizing quote from the founder of Wado Ryu Karate Hironori Ohtsuka, gives intriguing clues as to the value and influence that this particular kata holds. "Every technique (in Naihanchi) has its own purpose. I personally favour Naihanchi. It is not interesting to the eye, but it is extremely difficult to use. Naihanchi increases in difficulty with more time spent practicing it, however, there is something "deep" about it. It is fundamental to any move that requires reaction. Some people may call me foolish for my belief. However, I prefer this kata over all else and hence incorporate it into my movement."1 Many Wado karate-ka practice Naihanchi diligently, while remaining largely unaware of the background and long history of this unusual kata. -

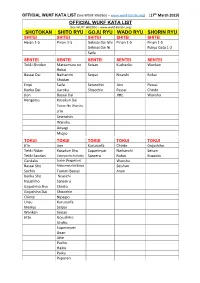

Official Wukf Kata List Shotokan Shito Ryu Goju

OFFICIAL WUKF KATA LIST (See WUKF WebSite – www.wukf-Karate.org) [17th March 2019] OFFICIAL WUKF KATA LIST (See WUKF WebSite – www.wukf-Karate.org) SHOTOKAN SHITO RYU GOJU RYU WADO RYU SHORIN RYU SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI Heian 1-5 Pinan 1-5 Gekisai Dai Ichi Pinan 1-5 Pinan 1-5 Gekisai Dai Ni Fukyu Gata 1-2 Saifa SENTEI SENTEI SENTEI SENTEI SENTEI Tekki Shodan Matsumura no Seisan Kushanku Wankan Rohai Bassai Dai Naihanchi Seipai Niseishi Rohai Shodan Empi Saifa Seiunchin Jion Passai Kanku Dai Jiuroku Shisochin Passai Chinto Jion Bassai Dai Jitte Wanshu Hangetsu Kosokun Dai Tomari No Wanshu Ji'in Seienchin Wanshu Aoyagi Miojio TOKUI TOKUI TOKUI TOKUI TOKUI Ji'in Jion Kururunfa Chinto Gojushiho Tekki Nidan Kosokun Sho Suparimpai Naihanchi Seisan Tekki Sandan Ciatanyara No Kushanku Sanseru Rohai Kusanku Gankaku Sochin (Aragaki ha) Wanshu Bassai Sho Matsumura No Bassai Seishan Sochin Tomari Bassai Anan Kanku Sho Niseichi Nijushiho Sanseiru Gojushiho Sho Chinto Gojushiho Dai Shisochin Chinte Nipaipo Unsu Kururunfa Meikyo Seipai Wankan Seisan Jitte Gojushiho Unshu Suparimpei Anan Jitte Pacho Haiku Paiku Papuren KATA LIST - WUKF COMPETITION UECHI RYU KYOKUSHINKAI BUDOKAN GOSOKU RYU SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI Kanshiva Pinan 1-5 Heian 1-5 Kihon Ichi No Kata Sechin Kihon Yon No Kata Kanshu Kime Ni No Kata Seiryu (Kiyohide) Ryu No Kata Uke No Kata SENTEI SENTEI SENTEI SENTEI Sesan Geksai Dai Empi Ni No Kata Kanchin Tsuki No Kata Tekki 1-2 Kime No Kata Sanseryu Yantsu Bassai Dai Gosoku Tensho Kanku Dai Gosoku Yondan Saifa Jion Sanchin no -

The Shorin-Ryu Shorinkan of Williamsburg

Shorin-Ryu of Williamsburg The Shorin-Ryu Karate of Williamsburg Official Student Handbook Student Name: _________________________________________ Do not duplicate 1 Shorin-Ryu of Williamsburg General Information We are glad that you have chosen our school to begin your or your child’s journey in the martial arts. This handbook contains very important information regarding the guidelines and procedures of our school to better inform you of expectations and procedures regarding training. The quality of instruction and the training at our dojo are of the highest reputation and are designed to bring the best out of our students. We teach a code of personal and work ethics that produce citizens of strong physical ability but most importantly of high character. Students are expected to train with the utmost seriousness and always give their maximum physical effort when executing techniques in class. Instructors are always observing and evaluating our students based on their physical improvements but most of all, their development of respect, courtesy and discipline. Practicing karate is very similar to taking music lessons- there are no short cuts. As in music, there are people that possess natural ability and others that have to work harder to reach goals. There are no guarantees in music instruction that say someone will become a professional musician as in karate there are no guarantees that a student will achieve a certain belt. This will fall only on the student and whether they dedicate themselves to the instruction given to them. Our school does not offer quick paths to belts for a price as many commercial schools do. -

Yu Gup Ja Training Manual

Independent Tang Soo Do Association YU GUP JA TRAINING MANUAL © Copyright South Hills Karate Academy (Gene Garbowsky) No part of this document may be reproduced, copied or distributed without express permission from Master Gene Garbowsky Published May, 2013 A Message from Sa Bom Nim Gene Garbowsky, Kwan Jang Nim, Independent Tang Soo Do Association As a member of the Independent Tang Soo Do Association, I hope that you will come to re- alize the benefits of training in Tang Soo Do. As you may know, I have been teaching this Martial Art to hundreds of students over the past 30 years. I truly believe that every man, women, and child can benefit in many ways from practicing Martial Arts and Tang Soo Do. What are Martial Arts? It is the name given to the traditional systems of self-defense that have been practiced in Eastern and Western societies for thousands of years. Masters of the ancient Martial Arts ultimately discovered that mastery of the body comes through mas- tery of the mind. Therefore, the practice of Martial Arts is a way to a more fulfilling life. It is a path to freedom from self-confinement and the ultimate goal to mental and physical har- mony. Martial Arts training can absolutely change a person physically, psychologically, and emo- tionally in a very positive way. Regular physi- cal activity energizes the body, and since martial arts are based on natural law, the body can quickly reach top conditioning. Once physical changes develop, they soon lead to the mental and emotional improve- ments that many seek through the martial arts. -

Karate Rank Requirements

Karate Rank Requirements YOUTH RANK: KYUKYU - 9TH KYU (1 YELLOW TAG) (5-7 year olds) HAKKYU - 8TH KYU (2 YELLOW TAGS) YOUTH & ADULT RANKS NANAKYU - 7TH KYU (YELLOW BELT) ROKKYU - 6TH KYU (GREEN TAG) GOKYU - 5TH KYU (GREEN BELT) YONKYU - 4TH KYU (GREEN BELT / RED TAG) SANKYU - 3RD KYU (BROWN BELT) NIKYU - 2ND KYU IKKYU - 1ST KYU SHODAN 1 / 21 Karate Rank Requirements NIDAN SANDAN YONDAN YOUTH - KYUKYU - 9TH KYU (YELLOW TAG) (5-7 yr. olds) HOJO UNDO SHORIN KATA Punching None Blocks Front Kick Three Basic Stances: Front Stance Cat Stance Horse Stance YOUTH - HAKKYU - 8TH KYU (2 YELLOW TAGS) HOJO UNDO SHORIN KATA Punching Drill None Blocking Drill 2 / 21 Karate Rank Requirements Front Kick Three Basic Stances: Front Stance Cat Stance Horse Stance NANAKYU - 7TH KYU (YELLOW BELT) HOJO UNDO SHORIN KATA SHUDOKAN KATA Punching Drill None Taikyoku Shodan Blocking Drill Front Kick Three Basic Stances Front Stance Cat Stance Horse Stance IPPON KUMITE (ONE PERSON) Upper Series - Upper block-punch - Circle block-punch - Cross block-punch 3 / 21 Karate Rank Requirements Middle Series - Outer block-punch - Circle block-punch - Cross block-punch Lower Series - Lower block-punch OTHER TWO PERSON MATERIAL - Arm conditioning ROKKYU - 6TH KYU (YELLOW BELT /GREEN TAG) HOJO UNDO SHORIN KATA SHUDOKAN KATA Kyan Lines 1-3 None Taikyokyu Nidan Taikyokyu Sandan 4 / 21 Karate Rank Requirements IPPON KUMITE (ONE PERSON) Upper Series - Upper block-punch - Circle block-punch - Cross block-punch Middle Series - Outer block-punch - Circle block-punch - Cross block-punch -

Black Belt Kata Guidelines

Ueshiro Shorin-Ryu Karate USA founded by Grand Master Ansei Ueshiro under the direction of Hanshi Robert Scaglione BBllaacckk BBeelltt KKaattaa GGuuiiddeelliinneess These are the minimum time requirements for each Black Belt kata. In addition to the minimum times, each Black Belt must receive permission in advance from Hanshi or his/her Shihan* to begin a new kata. In most cases Hanshi or the Shihan will encourage a Black Belt to wait. o May begin learning a weapon kata (optional). Ik-Kyu ● Must learn Naihanchi nidan, Nihanchi sandan, and Ananku to test for Sho-Dan. o May learn Wankan a couple of months after attaining rank. o May learn Rohai approximately 1-2 years after Wankan. Sho-Dan o May learn Wanshu approximately 1- 2 years after Rohai. ● Must demonstrate all kata up to and including Wankan to test for Ni-Dan. o May learn Passai approximately 1 -2 years after Wanshu. Ni-Dan ● Must demonstrate all kata up to and including Wanshu to test for San-Dan. o May learn Chinto approximately 2 -3 years after Passai. San-Dan ● Must demonstrate one Fukyugata, Pinan and Naihanchi kata and all Black Belt kata up to and including Passai to test for Yon-Dan. o May learn Gojushiho approximately 3 years after Chinto. Yon-Dan ● Must demonstrate one Fukyugata, Pinan and Naihanchi kata and all Black Belt kata up to and including Chinto to test for Go-Dan. ● Must demonstrate one Fukyugata, Pinan and Naihanchi kata Go-Dan and all Black Belt kata up to and including Gojushiho to test for Roku-Dan. -

March, 2018 – Issue #3 – Volume 4 Karate for Life

March, 2018 – Issue #3 – Volume 4 Karate for Life - in The Villages th Sensei Lee Aiello – 7 Degree Black Belt ___________________________________________________________ We meet Mondays at Lake Miona 11 to 12:15; Wednesdays at Seabreeze 11 to 12:15 and every Thursday we have a practice session (especially good for newcomers) at Laurel Manor 1 PM to 2:30 PM for everyone and 2:30 to 3:45 for newcomers. Instructor for Newcomer’s Session: Black Belt, Ron Resseguie, Assisted by Purple Belt with Black Stripe, Carl Phelps Very good time at the anniversary dinner/dance on March 3rd. Thank you to all who worked to make it happen and to those of you who came to enjoy it! WHITE BELT TESTING (for Yellow) will be on Wednesday, May 9th. Everyone wear their Black Gi please Various Styles of Karate: Sensei Aiello’’s style is Shorei Ryu and some Shotokan, Sensei Kennedy’’s style is Shorin Ryu, Hanshi Bowles style is Shuri Ryu - all four styles are extremely similar. Semsei Aiello said that they combined the styles and call our style, that we all now study, Shorei Kempo. He mentioned that all styles, with the exception of Shotokan, come from the same area in Okinawa. What are the different types of karate? (question that I asked Google) The four earliest karate styles developed in Japan are Shotokan, Wado-ryu, Shito-ryu, and Goju-ryu. The first three styles find their origins in the Shorin- Ryu style from Shuri, Okinawa, while Goju-ryu finds its origins in Naha. Sensei Aiello and Sensei Kennedy were wondering out loud one day how many katas we have learned. -

Naihanchi / Tekki Le Kata Le Plus Meurtrier Du Karaté ?

Naihanchi / Tekki Le kata le plus meurtrier du karaté ? Traduit de l'anglais par Karim Benakli Le kata Naihanchi (Tekki en Shotokan) est pratiqué par la majorité des styles de karaté. On dit du terme 'Naihanchi' qu'il signifie 'combattre de coté' à cause de l'embusen particulier de ce kata. Cet embusen mène souvent de nombreux karatékas à penser que ce kata est destiné à combattre sur un bateau, dans un couloir ou adossé à un mur. Comme nous le verrons ci-après, les pas sur le coté de ce kata n'ont rien à voir avec un éventuel combat dans un couloir mais on tout à voir avec la mise en incapacité effective d'un adversaire. En Shotokan, le kata a été renommé 'Tekki', qui se traduit par 'la position du cavalier', probablement sur base de la position dans laquelle les pratiquants de Shotokan effectuent le kata. Dans le temps, Naihanchi était souvent le premier kata enseigné mais de nos jours il est abordé à la ceinture marron. Naihanchi n'est pas très impressionnant visuellement, il n'y a aucune technique flamboyante et aucun saut sophistiqué, et il en résulte que peu de pratiquants l'apprécient. Ce kata a peu de chance de faire remporter quelque trophée que ce soit et est habituellement appris et pratiqué à contrecœur, dans le but unique de satisfaire aux exigences des passages de grade. Personnellement, je trouve cela honteux, et de mon point de vue ce kata a énormément à offrir à tout karatéka. Il semble que ce soit Sokon Matsumura (1796-1893) qui ait introduit Naihanchi dans le karaté.