Challenging a Theory of Autism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

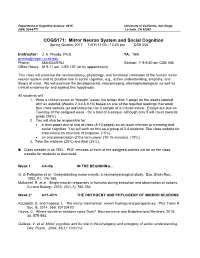

Mirror Neuron System and Social Cognition Spring Quarter 2017 Tuth 11:00 - 12:20 Pm CSB 005

Department of Cognitive Science 0515 University of California, San Diego (858) 534-6771 La Jolla, CA 92093 COGS171: Mirror Neuron System and Social Cognition Spring Quarter 2017 TuTH 11:00 - 12:20 pm CSB 005 Instructor: J. A. Pineda, Ph.D. TA: TBN [email protected] Phone: 858-534-9754 SeCtion: F 9-9:50 am CSB 005 OffiCe Hours: M 9-11 am, CSB 107 (or by appointment) This class will examine the neuroanatomy, physiology, and funCtional Correlates of the human mirror neuron system and its putative role in soCial Cognition, e.g., aCtion understanding, empathy, and theory of mind. We will examine the developmental, neuroimaging, electrophysiologiCal, as well as clinical evidence for and against this hypothesis. All students will: 1. Write a CritiCal review or “thought” essay (no longer than 1 page) on the weeks labeled with an asterisk (Weeks 2,3,4,6,8,10) based on one of the required readings that week. See Class website (or ask instruCtor) for a sample of a CritiCal review. Essays are due on Tuesday of the assigned week - for a total of 6 essays, although only 5 will count towards grade (25%). 2. You will also be responsible for: • a term paper due at end of class (8-10 pages) on an issue relevant to mirroring and social cognition. You will work on this as a group of 3-4 students. See Class website for instruCtions on structure of proposal. (15%) • an oral presentation of the term paper (10-15 minutes). (10%) 3. Take the midterm (25%) and final (25%). -

The Mirror Neuron System: How Cognitive Functions Emerge from Motor Organization Leonardo Fogassi

The mirror neuron system: How cognitive functions emerge from motor organization Leonardo Fogassi To cite this version: Leonardo Fogassi. The mirror neuron system: How cognitive functions emerge from motor or- ganization. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, Elsevier, 2010, 77 (1), pp.66. 10.1016/j.jebo.2010.04.009. hal-00921186 HAL Id: hal-00921186 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00921186 Submitted on 20 Dec 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Accepted Manuscript Title: The mirror neuron system: How cognitive functions emerge from motor organization Author: Leonardo Fogassi PII: S0167-2681(10)00177-0 DOI: doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2010.04.009 Reference: JEBO 2604 To appear in: Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization Received date: 26-7-2009 Revised date: 19-4-2010 Accepted date: 20-4-2010 Please cite this article as: Fogassi, L., The mirror neuron system: How cognitive functions emerge from motor organization, Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization (2010), doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2010.04.009 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. -

Empathy, Mirror Neurons and SYNC

Mind Soc (2016) 15:1–25 DOI 10.1007/s11299-014-0160-x Empathy, mirror neurons and SYNC Ryszard Praszkier Received: 5 March 2014 / Accepted: 25 November 2014 / Published online: 14 December 2014 Ó The Author(s) 2014. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract This article explains how people synchronize their thoughts through empathetic relationships and points out the elementary neuronal mechanisms orchestrating this process. The many dimensions of empathy are discussed, as is the manner by which empathy affects health and disorders. A case study of teaching children empathy, with positive results, is presented. Mirror neurons, the recently discovered mechanism underlying empathy, are characterized, followed by a theory of brain-to-brain coupling. This neuro-tuning, seen as a kind of synchronization (SYNC) between brains and between individuals, takes various forms, including frequency aspects of language use and the understanding that develops regardless of the difference in spoken tongues. Going beyond individual- to-individual empathy and SYNC, the article explores the phenomenon of syn- chronization in groups and points out how synchronization increases group cooperation and performance. Keywords Empathy Á Mirror neurons Á Synchronization Á Social SYNC Á Embodied simulation Á Neuro-synchronization 1 Introduction We sometimes feel as if we just resonate with something or someone, and this feeling seems far beyond mere intellectual cognition. It happens in various situations, for example while watching a movie or connecting with people or groups. What is the mechanism of this ‘‘resonance’’? Let’s take the example of watching and feeling a film, as movies can affect us deeply, far more than we might realize at the time. -

Mirror Neurons and Their Reflections

Open Access Library Journal Mirror Neurons and Their Reflections Mehmet Tugrul Cabioglu1, Sevgin Ozlem Iseri2 1Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, Baskent University, Ankara, Turkey 2Department of Clinical Biochemistry, Faculty of Medicine, Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey Received 23 October 2015; accepted 7 November 2015; published 12 November 2015 Copyright © 2015 by authors and OALib. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract Human mirror neuron system is believed to provide the basic mechanism for social cognition. Mirror neurons were first discovered in 1990s in the premotor area (F5) of macaque monkeys. Besides the premotor area, mirror neuron systems, having different functions depending on their locations, are found in various cortical areas. In addition, the importance of cingulate cortex in mother-infant relationship is clearly emphasized in the literature. Functional magnetic resonance imaging, electroencephalography, transcortical magnetic stimulation are the modalities used to evaluate the, activity of mirror neurons; for instance, mu wave suppression in electroencephalo- graphy recordings is considered as an evidence of mirror neuron activity. Mirror neurons have very important functions such as language processing, comprehension, learning, social interaction and empathy. For example, autistic individuals have less mirror neuron activity; therefore, it is thought that they have less ability of empathy. Responses of mirror neurons to object-directed and non-object directed actions are different and non-object directed action is required for the activa- tion of mirror neurons. Previous researchers find significantly more suppression during the ob- servation of object-directed movements as compared to mimed actions. -

Social Cognition and the Mirror Neuron System of the Brain

Motivating Questions Social Cognition and the Mirror How do our brains perceive the Neuron System of the Brain mental states of others despite their inaccessibility? How do we understand the actions, emotions and the intentions of others? Rationally? Intuitively? Jaime A. Pineda, Ph.D. Cognitive Neuroscience Laboratory How do we understand first- COGS1 class and third-person experiences? Classic Explanation A Different Perspective Theory-Theory (argument from analogy; disembodied Simulation Theory knowledge; visual hypothesis) (Direct-matching hypothesis; embodied knowledge) Map visual information onto Involves striate, extrastriate, motor representations of the inferotemporal lobe and same action superior temporal sulcus, among others Mirroring systems bridges between perception and action that allow for simulation Mirror neurons EEG Mu rhythms A Different Perspective The Mirror Neuron System Simulation Theory (Direct-matching hypothesis; embodied knowledge) Map visual information onto motor representations of the same action Mirroring systems bridges between perception and action that allow for simulation Mirror neurons EEG Mu rhythms Iacoboni and Dapretto, Nature Reviews, 2006,7:942-951 1 Biological Motion Biological Motion Perception: Monkeys Visual system's ability to Gender recover object information Activity engaged in Perret and colleagues from sparse input Emotional state (1989; 1990; 1994) Cells in superior temporal polysensory area (STPa) of the macaque temporal cortex appear sensitive to biological motion Oram & Perrett, J. Cog. Neurosci., 1994, 6(2), 99-116 Biological Motion Perception: Humans Brain Circuit for Social Perception (SP) An area in the superior • SP is processing of temporal sulcus (STS) in information that results in humans responds to the accurate analysis of biological motion the intentions of others • STS involved in the Other areas do as well, processing of a variety of including frontal cortex, social signals SMA, insula, thalamus, amygdala Grossman et al. -

EEG Evidence for Mirror Neuron Activity During the Observation of Human and Robot Actions: Toward an Analysis of the Human Qualities of Interactive Robots

ARTICLE IN PRESS Neurocomputing 70 (2007) 2194–2203 www.elsevier.com/locate/neucom EEG evidence for mirror neuron activity during the observation of human and robot actions: Toward an analysis of the human qualities of interactive robots Lindsay M. Obermana,b,Ã, Joseph P. McCleeryb, Vilayanur S. Ramachandrana,b,c, Jaime A. Pinedac,d aCenter for Brain and Cognition, UC San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093-0109, USA bDepartment of Psychology, UC San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093-0109, USA cDepartment of Neurosciences, UC San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093-0662, USA dDepartment of Cognitive Science, UC San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093-0515, USA Received 4 February 2005; received in revised form 17 January 2006; accepted 1 February 2006 Available online 2 January 2007 Abstract The current study investigated the properties of stimuli that lead to the activation of the human mirror neuron system, with an emphasis on those that are critically relevant for the perception of humanoid robots. Results suggest that robot actions, even those without objects, may activate the human mirror neuron system. Additionally, both volitional and nonvolitional human actions also appear to activate the mirror neuron system to relatively the same degree. Results from the current studies leave open the opportunity to use mirror neuron activation as a ‘Turing test’ for the development of truly humanoid robots. r 2007 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Keywords: Mirror neuron; Humanoid; Anthropomorphic; Robot; Volition; Action observation; Social interaction 1. Introduction observation/execution network known as the ‘mirror neuron’ system. A great deal of robotics research has recently investi- Single unit studies indicate that neurons in area F5 of the gated issues surrounding the creation of robots that are macaque premotor cortex, which are indistinguishable able to socially interact with humans and other robots from neighboring neurons in terms of their motor proper- [7,8,36]. -

Mirror Neuron System Could Result in Some of the Symptoms of Autism

Broken Mirrors: A Theory of Autism Scienctific American - October 16, 2006 By Vilayanur S. Ramachandran and Lindsay M. Oberman At first glance you might not notice anything odd on meeting a young boy with autism. But if you try to talk to him, it will quickly become obvious that something is seriously wrong. He may not make eye contact with you; instead he may avoid your gaze and fidget, rock his body to and fro, or bang his head against the wall. More disconcerting, he may not be able to conduct anything remotely resembling a normal conversation. Even though he can experience emotions such as fear, rage and pleasure, he may lack genuine empathy for other people and be oblivious to subtle social cues that most children would pick up effortlessly. In the 1940s two physicians--American psychiatrist Leo Kanner and Austrian pediatrician Hans Asperger-- independently discovered this developmental disorder, which afflicts about 0.5 percent of American children. Neither researcher had any knowledge of the other's work, and yet by an uncanny coincidence each gave the syndrome the same name: autism, which derives from the Greek word autos, meaning "self." The name is apt, because the most conspicuous feature of the disorder is a withdrawal from social interaction. More recently, doctors have adopted the term "autism spectrum disorder" to make it clear that the illness has many related variants that range widely in severity but share some characteristic symptoms. Ever since autism was identified, researchers have struggled to determine what causes it. Scientists know that susceptibility to autism is inherited, although environmental risk factors also seem to play a role [see "The Early Origins of Autism," by Patricia M. -

Neuroimaging the Human Mirror Neuron System

Opinion Crossmodal and action-specific: neuroimaging the human mirror neuron system 1,2,3 4,5 4 Nikolaas N. Oosterhof , Steven P. Tipper , and Paul E. Downing 1 Centro Interdipartimentale Mente/Cervello (CIMeC), Trento University, Trento, Italy 2 Department of Psychological & Brain Sciences, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, USA 3 Department of Psychology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA 4 Wales Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience, School of Psychology, Bangor University, Bangor, UK 5 Department of Psychology, University of York, York, UK The notion of a frontoparietal human mirror neuron the context of different actions (e.g., grasping to eat or system (HMNS) has been used to explain a range of placing an object), suggesting a mechanism by which the social phenomena. However, most human neuroimag- final goal of a series of actions could be understood [2,3]. ing studies of this system do not address critical ‘mirror’ Fourth, the class of mirror neurons is heterogeneous with properties: neural representations should be action spe- respect to tuning properties of individual neurons on vari- cific and should generalise across visual and motor ous dimensions including hand and direction preference modalities. Studies using repetition suppression (RS) [4], distance to the observed actor [8], and viewpoint of the and, particularly, multivariate pattern analysis (MVPA) observed action [9]. highlight the contribution to action perception of ante- If humans are endowed with such neurons as well, many rior parietal regions. Further, these studies add to have argued that this would provide an explanation for mounting evidence that suggests the lateral occipito- how people solve the ‘correspondence problem’ [4,10] of temporal cortex plays a role in the HMNS, but they offer imitation and of learning and understanding actions per- less support for the involvement of the premotor cortex. -

Mirror Neuron: a Neurological Approach to Empathy Giacomo Rizzolatti1,3 and Laila Craighero2

Mirror neuron: a neurological approach to empathy Giacomo Rizzolatti1,3 and Laila Craighero2 Summary Humans are an exquisitely social species. Our survival and success depend criti- cally on our ability to thrive in complex social situations. But how do we under- stand others? Which are the mechanisms underlying this capacity? In the present essay we discuss a general neural mechanism (“mirror mecha- nism”) that enables individuals to understand the meaning of actions done by others, their intentions, and their emotions, through activation of internal repre- sentations coding motorically the observed actions and emotions. In the first part of the essay we will show that the mirror mechanism for “cold” actions, those devoid of emotional content, is localized in parieto-frontal cortical circuits. These circuits become active both when we do an action and when we ob- serve another individual doing the same action. Their activity allows the observer to understand the “what” of an action. We will show, then, that a “chained” organization of motor acts plus the mir- ror mechanism enable the observer to understand the intention behind an action (the “why” of an action) by observing the first motor act of an action. Finally, we will discuss some recent data showing that the mirror mechanism localized in other centers, like the insula, enables the observer to understand the emotions of others. We will conclude briefly discussing whether these biological data allow inferences about moral behavior. Introduction “How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it.” This famous sentence by Adam Smith (1759), which so nicely describes our empathic relation with others, contains two distinct concepts. -

Reading Sheet Music Activates the Mirror Neuron System of Musicians: an EEG Investigation

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship 2010 Reading sheet music activates the mirror neuron system of musicians: an EEG investigation. Lawrence Paul Behmer Western Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the Psychiatry and Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Behmer, Lawrence Paul, "Reading sheet music activates the mirror neuron system of musicians: an EEG investigation." (2010). WWU Graduate School Collection. 41. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/41 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reading sheet music activates the Mirror Neuron System of musicians: An EEG investigation By Lawrence Paul Behmer Jr. Accepted in Partial Completion Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Moheb A. Ghali, Dean of the Graduate School ADVISORY COMMITTEE Chair, Dr. Kelly J. Jantzen Dr. McNeel Jantzen Dr. Larry A. Symons MASTER’S THESIS In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non‐exclusive royalty ‐free right to archive, reproduce, distribute, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU. I represent and warrant this is my original work, and does not infringe or violate any rights of others. -

Action to Language Via the Mirror Neuron System

ACTION TO LANGUAGE VIA THE MIRROR NEURON SYSTEM Mirror neurons may hold the brain’s key to social interaction: each coding not only a particular action or emotion, but also the recognition of that action or emotion in others. The Mirror System Hypothesis adds an evolutionary arrow to the story: from the mirror system for hand actions, shared with monkeys and chimpanzees, to the uniquely human mirror system for language. In this volume, written to be accessible to a wide audience, experts from child development, computer science, linguistics, neuroscience, primat- ology, and robotics present and analyze the mirror system and show how studies of action and language can illuminate each other. Topics discussed in the 15 chapters include the following. What do chimpanzees and humans have in common? Does the human capabil- ity for language rest on brain mechanisms shared with other animals? How do human infants acquire language? What can be learned from imaging the human brain? How are sign- and spoken-language related? Will robots learn to act and speak like humans? MICHAEL A. ARBIB is the Fletcher Jones Professor of Computer Science, as well as a Professor of Biological Sciences, Biomedical Engineering, Electrical Engineering, Neuroscience and Psychology at the University of Southern California (USC), which he joined in 1986. He has been named as one of a small group of University Professors at USC in recognition of his contributions across many disciplines. ACTION TO LANGUAGE VIA THE MIRROR NEURON SYSTEM edited by MICHAEL A. ARBIB University of Southern California CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521847551 © Cambridge University Press 2006 This publication is in copyright. -

Primate Mirror Neurons

Imitation Is The Sincerest Form of Flattery Image removed due to copyright restrictions. Photograph of musician playing a cello. Sarinana, Joshua MIT 2007 Imitation Is The Sincerest Form of Flattery Image removed due to copyright restrictions. Photo of a tennis player. Sarinana, Joshua MIT 2007 Monkeys Imitate Too Images removed due to copyright restrictions. Photos of George W. Bush and chimpanzees wearing similar expressions. Sarinana, Joshua MIT 2007 Coupling Observation of an action with the Execution of an action Sarinana, Joshua MIT 2007 The Mirror Neuron System Sarinana, Joshua MIT 2007 Requisites for Observational Learning • Watch/Listen to human or human like action • Integrate what was watched/listened to with motor preparation • Execute the action from the learning episode • Place yourself in the position of the observed* Sarinana, Joshua MIT 2007 Overview • Anatomy and Physiology of Monkey Mirror Neuron System • What Else Do Mirror Neurons Encode? • Homologies in the Human Mirror Neuron System • Language, Empathy and Autism Sarinana, Joshua MIT 2007 Overview • Anatomy and Physiology of Monkey Mirror Neuron System • What Else Do Mirror Neurons Encode? • Homologies in the Human Mirror Neuron System • Language, Empathy and Autism Sarinana, Joshua MIT 2007 Monkey Cortex Source: Fig. 6 in Nieder, Andreas. "Counting on Neurons: the Neurobiology of Numerical Competence." Nature Reviews Neuroscience 6 (2005): 177-190. Courtesy of the author. Used with permission. Sarinana, Joshua MIT 2007 Parietal and Prefrontal Dependent Motor Areas Leg Leg Leg PE PEc Eye F2 F1 Arm F7 Arm Arm Opt AS l P PG Eye Arm F C Face PFG Face a 8 c PF Arm A F4 e Arm PGop P Eye r m PFop F5 Lu Al L 10 STS Figure by MIT OpenCourseWare.