FLYING LESSONS for May 23, 2019 by Thomas P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monroe County Developers Streamlining Guide

Prepared by the Monroe County Economic Development Corporation Revised March 2018 Table of Contents Monroe County Board of Commissioners ......................................................................... i Monroe County Economic Development Corporation ..................................................... i Monroe County Economic Development Corporation ..................................................... ii Streamlining Development Task Force .............................................................................. ii Streamlining Development User’s Guide .......................................................................... iii Mission Statement ............................................................................................................. iii Goals ................................................................................................................................... iii Keeping this Guide Up to Date ..........................................................................................iv 1. Partnership Pledge ........................................................................................................... 1-1 Streamlining Development Partnership Signatories ......................................................1-1 2. Partnership Assistance & Web Links .............................................................................. 2-1 County & State Organizations ......................................................................................... 2-1 Monroe County Municipalities -

Monroe County Streamlining Guide

Prepared by the Monroe County Economic Development Corporation Revised March 2018 Table of Contents Monroe County Board of Commissioners ......................................................................... i Monroe County Economic Development Corporation ..................................................... i Monroe County Economic Development Corporation ..................................................... ii Streamlining Development Task Force .............................................................................. ii Streamlining Development User’s Guide .......................................................................... iii Mission Statement ............................................................................................................. iii Goals ................................................................................................................................... iii Keeping this Guide Up to Date ..........................................................................................iv 1. Partnership Pledge ........................................................................................................... 1-1 Streamlining Development Partnership Signatories ......................................................1-1 2. Partnership Assistance & Web Links .............................................................................. 2-1 County & State Organizations ......................................................................................... 2-1 Monroe County Municipalities -

5 PAI.150.Noise Abt

DETROIT METROPOLITAN WAYNE COUNTY AIRPORT FAR PART 150 NOISE COMPATIBILITY STUDY UPDATE CHAPTERINVENTORY A Inventory Introduction Detroit Metropolitan Wayne County Airport (DTW) is an integral component of the transportation infrastructure serving the Detroit Metropolitan area, southeast Michigan, and northwest Ohio. Because of its airfield and facility capabilities, Detroit Metropolitan Wayne County Airport is also a vital part of the national system of airports. The Airport serves as not only the City of Detroit’s front door by providing visitors with an important first impression of the community, but also is the state's largest airport. The Airport provides transportation facilities that are an absolute necessity for some businesses, and a "required" convenience for others. Additionally, Detroit Metropolitan Wayne County Airport provides recreational and leisure traveler’s convenient access to air transportation with convenient non-stop and connecting service to many popular destinations. This Federal Aviation Regulation (FAR) Part 150 Noise Compatibility Planning Study is an update of a 1992 Study that was adopted by Wayne County and approved by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) in 1993. The Wayne County Airport Authority has implemented many of the recommendations contained in the previous FAR Part 150 Study. However, since completion of the previous study, there have been changes to the airfield, type of aircraft, and the number of aircraft operating at the airport. As such, many of these changes have likely resulted in changes to noise exposure and therefore the need for an update to the previous Study. The purpose of this airport facilities INVENTORY chapter of the Part 150 Study is to establish a baseline of information about existing airport facilities and operations, as well as local land use. -

2017 MASTER PLAN Frenchtown Township · Monroe County · Michigan

2017 MASTER PLAN Frenchtown Township · Monroe County · Michigan Master Plan Frenchtown Charter Township, Monroe County, Michigan Adopted July 25, 2017 Prepared with the assistance of: COMMUNITY PLANNING CONSULTANTS 235 E. Main Street, Suite 105 Northville, Michigan 48167 Telephone: (248) 596-0920 Acknowledgments TOWNSHIP BOARD James McDevitt, Supervisor Mark Baker, Clerk Julie Ellison, Treasurer Hedwig Kaufman, Trustee Jack Lindquist, Trustee Alan VanWashenova, Trustee Kraig Yoas, Trustee Rhonda Sommers, Former Treasurer Don Lingar, Former Trustee PLANNING COMMISSION Ignazio Cuccia, Chair Steve Hyder Hedwig Kaufman Hillary Schmitz Dennis Staelgraeve Paul Thoma Robert Thoma Manfred Klein, Former Member Thomas Fox, Former Member TOWNSHIP STAFF AND CONSULTANTS Joseph Lehmann, Building Official Kerry Bondy, Attorney, Petrangelo, Bondy, and Crossley Barry Buschmann, Engineer , Mannik and Smith Mark Mathe, Engineer, Mannik and Smith Sue Iott-Garrison, Assessor Larry Chinavare, Parks and Recreation Director Wendy Stevens, Fire Chief Josh Maddox, Fire Inspector Rich Weirich, Water Utility Director MASTER PLAN : ADOPTED JULY 25, 2017 iii FRENCHTOWN CHARTER TOWNSHIP, MONROE COUNTY, MICHIGAN iv MASTER PLAN : ADOPTED JULY 25, 2017 FRENCHTOWN CHARTER TOWNSHIP, MONROE COUNTY, MICHIGAN Table of Contents 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................. 9 2. Land Use Plan ....................................................................................................... -

Health and Public Safety Committee

Health and Public Safety Committee Karen Bargy Brenda Ricksgers, Chair Melissa Zelenak Minutes March 21, 2018 Members present: Brenda Ricksgers, Karen Bargy, Melissa Zelenak Members absent: Others present: Pete Garwood, Mathew Cooke, Ed Boettcher, Dawn LaVanway, Dean Pratt, Dan Bean, 1. The meeting was called to order at 9:00 a.m. by Chair Brenda Ricksgers 2. Public Comment Undersheriff Dean Pratt read a written statement (see attached pgs. 7-8) regarding the actions taken by the Sheriff’s Department during the March 10, 2018, homicide investigation. Mr. Pratt also read the following statement from a relative of the 15-year-old survivor: “I strongly feel that all the law enforcement involved including the Antrim County Sheriff Department, Kalkaska County Sheriff’s Department, Michigan State police, EMS, fire dept, Munson hospital did a great job with such a tragic situation. I am confident that law enforcement had it handled. If any of you want to do anything helpful and kind, keep all involved in your thoughts and prayers, especially for the man who passed from his injuries and his wife and family. If you don’t have anything nice or helpful to say, keep it to yourself. There is a lot of families hurting from this tragedy and I want to remind you to be kind to one another and keep in mind most posts on social media regarding this tragedy have not been accurate. I wish I had known about this meeting so I could share my thoughts. ” Jim Janisse, Antrim County Detective Sergeant, stated that he was downstate during the incident but reminded the Committee the suspect was captured within eight hours. -

Airnav.Com 2009. FAA Information Effective 07/02/2009 Re Willow Run

AirNav: KYIP - Willow Run Airport Page 1 of 5 1606 users online Willow Run Airport KYIP Detroit, Michigan, USA GOING TO DETROIT? Loc | Ops | Rwys | IFR | FBO | Links FAA INFORMATION EFFECTIVE 02 JULY 2009 Com | Nav | Svcs | Stats | Notes Location FAA Identifier: YIP Lat/Long: 42-14-15.8000N / 083-31-48.3000W 42-14.263333N / 083-31.805000W 42.2377222 / -83.5300833 $3.75 $2.84 (estimated) Elevation: 716 ft. / 218.2 m (surveyed) Variation: 06W (1995) From city: 24 miles SW of DETROIT, MI Time zone: UTC -4 (UTC -5 during Standard Time) Zip code: 48111 Airport Operations Airport use: Open to the public Activation date: 12/1942 Sectional chart: DETROIT Control tower: yes ARTCC: CLEVELAND CENTER FSS: LANSING FLIGHT SERVICE STATION NOTAMs facility: YIP (NOTAM-D service available) Attendance: CONTINUOUS Wind indicator: lighted Segmented circle: no Lights: DUSK-DAWN Beacon: white-green (lighted land airport) Landing fee: yes, LANDING FEE IS BASED ON ACFT GWT. Fire and rescue: ARFF index A Airline operations: ARFF INDEX E SVC AVBL ON REQUEST CALL 734-485-6660. International operations: customs landing rights airport US CUSTOMS USER FEE ARPT. ALL BILLING THRU WAYNE CO Road maps at: MapQuest MapPoint Yahoo! ARPT AUTHORITY; FOR CUSTOMS CLNC 1 HR MIN ADVANCE Maps Google Rand McNally Satellite photo at: TerraServer Virtual Earth NOTIFICATION REQD. PILOTS MUST CTC U.S. CUSTOMS ON 313-226-3140; RQ FOR CUSTOMS SVC BY FAA FLIGHT PLAN IS Aerial photo NOT ACCEPTED. WARNING: Photo may not be current or correct US CUSTOMS USER FEE ARPT. Airport Communications -

Michigan Aeronautics Commission Meeting Agenda

Michigan Aeronautics Commission Meeting Agenda May 26, 2021 – 10:00 a.m. Microsoft Teams Meeting/Conference Call Dial 1-248-509-0316; Conference ID 323697404# I. OPENING REMARKS, PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE, and ROLL CALL Chairperson Rick Fiddler II. COMMISSION BUSINESS A. Minutes of the March 24, 2021 Meeting B. Request for Approval of Revised Air Service Program Guidelines C. Request for Approval and Transfer of Appropriated Funds – Alissa VanHoof Airport Sponsor Contracts 1. Padgham Field, Allegan 2. Beaver Island Airport, Beaver Island 3. Beaver Island Airport, Beaver Island 4. Branch County Memorial Airport, Coldwater 5. Willow Run Airport, Detroit 6. Delta County Airport, Escanaba 7. Delta County Airport, Escanaba 8. Delta County Airport, Escanaba 9. Delta County Airport, Escanaba 10. Frankfort Dow Memorial Field, Frankfort 11. Abrams Municipal Airport, Grand Ledge 12. Abrams Municipal Airport, Grand Ledge 13. Hastings Airport, Hastings 14. Ionia County Airport, Ionia 15. Ford Airport, Iron Mountain/Kingsford 16. Ford Airport, Iron Mountain/Kingsford 17. Gogebic-Iron County Airport, Ironwood 18. Gogebic-Iron County Airport, Ironwood 19. Sawyer International Airport, Marquette 20. Sawyer International Airport, Marquette 21. Menominee Regional Airport, Menominee 22. Mount Pleasant Municipal Airport, Mount Pleasant 23. Oakland Southwest Airport, New Hudson 24. Jerry Tyler Memorial Airport, Niles 25. Owosso Community Airport, Owosso 26. Saint Clair County International Airport, Port Huron 27. Chippewa County International Airport, Sault Ste Marie 28. Chippewa County International Airport, Sault Ste Marie 29. Chippewa County International Airport, Sault Ste Marie 30. Cherry Capital Airport, Traverse City 31. Cherry Capital Airport, Traverse City 32. Cherry Capital Airport, Traverse City 33. -

FAA Facts Federal Aviation Administration, Washington, D.C

FAA Facts Federal Aviation Administration, Washington, D.C. 20591 _____________________________________________________________________ Cleveland-Detroit Metroplex The Federal Aviation Administration’s Next Generation Air Transportation System, or NextGen, is the ongoing transformation of air traffic control technologies and procedures in the United States. You might think of this transition as similar to moving from paper maps to GPS when you drive your car. In addition to improving navigation, NextGen brings other benefits: • NextGen enhances aviation safety, reduces carbon emissions and modernizes air traffic procedures to today’s standards. o A key NextGen goal is to safely improve the way aircraft navigate complex, metropolitan areas, which we call Metroplexes, to make flight routes and airports more efficient. • The FAA has identified multiple Metroplex areas in the United States. Each Metroplex includes one or more commercial airports that serve at least one major city: o A Metroplex allows the FAA to improve regional traffic movement by making the best use of airspace and procedures, using precise, satellite-based navigation. • Use of NextGen procedures in these areas could improve on-time performance, which would benefit the region and the entire national airspace system. Cleveland-Detroit The airspace surrounding Cleveland and Detroit has a large number of air traffic procedures which have not been changed for many years. • While these procedures are safe, most are inefficient due to advances in technology. This is one of the reasons why the airspace surrounding Cleveland Hopkins and Detroit Metro airports has been identified for Metroplex development. O V E R The proposed Metroplex would allow for more direct and efficient routing of aircraft into and out of Cleveland and Detroit, enhancing aviation safety, and reducing flight delays above these communities. -

Michigan Aeronautics Commission

Michigan Aeronautics Commission Wednesday, March 28, 2018 – 10:00 a.m. Aeronautics Auditorium 2700 Port Lansing Road, Lansing, Michigan I. OPENING REMARKS AND THE PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE Chairman Dave VanderVeen II. COMMISSION BUSINESS A. Minutes of the January 25, 2018 Meeting B. Request for Approval and Transfer of Appropriated Funds – Elyse Lower Air Service Program Grants 1. Alpena County Regional Airport, Alpena 2. Willow Run Airport, Detroit 3. Delta County Airport, Escanaba 4. Bishop International Airport, Flint 5. Gerald R. Ford International Airport, Grand Rapids 6. Houghton County Memorial, Hancock 7. Ford Airport, Iron Mountain Kingsford 8. Gogebic Iron County Airport, Ironwood 9. Kalamazoo/Battle Creek International, Kalamazoo 10. Capital Region International, Lansing 11. Manistee County – Blacker, Manistee 12. Sawyer International, Marquette 13. Muskegon County Airport, Muskegon 14. Pellston Regional Airport of Emmet County, Pellston 15. Chippewa County International Airport, Sault Ste. Marie 16. Cherry Capital Airport, Traverse City Airport Sponsor Contracts 1. Antrim County Airport, Bellaire 2. Wexford County Airport, Cadillac 3. Fitch H. Beach Municipal, Charlotte 4. Branch County Memorial, Coldwater 5. Dowagiac Municipal Airport, Dowagiac 6. Frankfort Dow Memorial Field, Frankfort 7. Gladwin Zettel Municipal, Gladwin 8. Abrams Municipal Airport, Grand Ledge 9. Greenville Municipal Airport, Greenville 10. Greenville Municipal Airport, Greenville 11. Oceana County Airport, Hart/Shelby 12. Oceana County Airport, Hart/Shelby 13. Lakeview - Griffith Field, Lakeview 14. Mason County Airport, Ludington 15. Mason County Airport, Ludington 16. Manistee County – Blacker, Manistee 17. Marlette Township Airport, Marlette 18. Marlette Township Airport, Marlette 19. Marlette Township Airport, Marlette 20. Luce County Airport, Newberry 21. Presque Isle County, Rogers City 22. -

Special Meeting

MICHIGAN AERONAUTICS COMMISSION Minutes of Meeting Lansing, Michigan May 14, 2020 Pursuant to Section 31 of Act 327 of the Public Acts of 1945 and Executive Directive 2020-75, the Commissioners of the Michigan Aeronautics Commission met via video conference call, on Thursday, May 14, 2020. Members Present Members Absent Roger Salo, Chair Laura Mester, Designee - MDOT Rick Fiddler, Vice Chair Dr. Brian Smith, Commissioner Russ Kavalhuna, Commissioner Kelly Burris, Commissioner Brig. Gen. Bryan Teff, Designee – MDMVA Kevin Jacobs, Designee – MDNR F/Lt. Brian Bahlau, Designee – MSP Mike Trout, Director Bryan Budds, Commission Advisor Alicia Morrison, Commission Assistant I. OPENING REMARKS Director Mike Trout began by explaining the special meeting was being held today via video conference call in accordance with Executive Directive 2020-75, enacted to allow teleconference public meetings due to the COVID-19 pandemic. He welcomed all who were participating and asked for their patience while navigating through the video conferencing meeting format. Director Trout stated the primary purpose of the special meeting was to address and vote on the transfer of Coronavirus Aid Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act funding to airports. He noted he would not be giving his normal Director’s Report, however, there will be time given for Commissioner and public comment. He also thanked the Commissioners for coming together on short notice and encouraged anyone with questions related to the Covid-19 outbreak to visit www.michigan.gov/coronavirus. Director Trout then turned the meeting over to Chairperson Roger Salo. The May 14, 2020 special Michigan Aeronautics Commission (MAC) meeting was officially called to order by Chair Roger Salo at 10:00 a.m. -

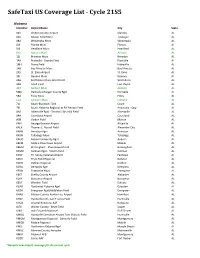

Safetaxi US Coverage List - Cycle 21S5

SafeTaxi US Coverage List - Cycle 21S5 Alabama Identifier Airport Name City State 02A Chilton County Airport Clanton AL 06A Moton Field Muni Tuskegee AL 08A Wetumpka Muni Wetumpka AL 0J4 Florala Muni Florala AL 0J6 Headland Muni Headland AL 0R1 Atmore Muni Atmore AL 12J Brewton Muni Brewton AL 1A9 Prattville - Grouby Field Prattville AL 1M4 Posey Field Haleyville AL 1R8 Bay Minette Muni Bay Minette AL 2R5 St. Elmo Airport St. Elmo AL 33J Geneva Muni Geneva AL 4A6 Scottsboro Muni-Word Field Scottsboro AL 4A9 Isbell Field Fort Payne AL 4R3 Jackson Muni Jackson AL 5M0 Hartselle-Morgan County Rgnl Hartselle AL 5R4 Foley Muni Foley AL 61A Camden Muni Camden AL 71J Ozark-Blackwell Field Ozark AL 79J South Alabama Regional at Bill Benton Field Andalusia - Opp AL 8A0 Albertville Rgnl - Thomas J Brumlik Field Albertville AL 9A4 Courtland Airport Courtland AL A08 Vaiden Field Marion AL KAIV George Downer Airport Aliceville AL KALX Thomas C. Russell Field Alexander City AL KANB Anniston Rgnl Anniston AL KASN Talladega Muni Talladega AL KAUO Auburn University Rgnl Auburn AL KBFM Mobile Downtown Airport Mobile AL KBHM Birmingham - Shuttlesworth Intl Birmingham AL KCMD Cullman Rgnl - Folsom Field Cullman AL KCQF H L Sonny Callahan Airport Fairhope AL KDCU Pryor Field Regional Decatur AL KDHN Dothan Regional Dothan AL KDYA Dempolis Rgnl Dempolis AL KEDN Enterprise Muni Enterprise AL KEET Shelby County Airport Alabaster AL KEKY Bessemer Airport Bessemer AL KEUF Weedon Field Eufaula AL KGAD Northeast Alabama Rgnl Gadsden AL KGZH Evergreen Rgnl/Middleton -

20 Monroe County Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy 11

2011 MonroeCounty Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy Monroe County, Michigan 2011 Monroe County Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy This document prepared and published by the Monroe County Planning Department & Commission 125 East Second Street Monroe, MI 48161 (734) 240-7375 Fax (734) 240-7385 Robert P. Peven, AICP, Director Report Coordinator: Lee W. Markham, Planner Monroe County Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy Committee William P. Morris, Chairman Monroe County Planning Commission Mary K. Webb, Chairman Monroe County Board of Commissioners R. LaMar Frederick, Chairman August 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page FOREWORD ...................................................................................... 1 1. OPPORTUNITIES AND PROBLEMS ..................................................... 3 Opportunities .......................................................................................... 3 Problems................................................................................................ 25 2. BACKGROUND AND HISTORY ......................................................... 29 Economic Development in Monroe County ............................................ 29 Monroe County’s Economic Development Network ................................ 30 Relevant Websites .................................................................................. 31 Economic Development Highlights of 2010/2011 .................................. 32 Environment .........................................................................................