Making the Case for Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kimberly Adams Dalia Angrand Danielle Carniaux Alicia Ciocca

Mary Cregan Master Class The Woman in the Mirror May 20, 2019 Hosted by New-York Historical Society FELLOWS Kimberly Adams Broome Street Academy Charter School, grades 11, 12, teaching 9 years, English I have done work in both my Journalism and English 12 classes looking at texts through a gender lens and doing research surrounding both American and global gender dynamics. I am passionate about engaging students of all genders in reflection on how gender norms and gender discrimination affects us all, not just women. I also find it more important than ever to bring awareness to elements of intersectionality when discussing feminism. Dalia Angrand Williamsburg Preparatory School, grades 10, 11, teaching 18 years, English Students often start out nervous and resistant when I ask them to write narratives, or to write creatively in any way. However, that resistance almost always turns to excitement as they begin to list, draw, diagram, and free-write about their lives, drawing power from their own stories. Over time, they craft compelling narratives: authentic responses to experiences, both positive and negative, that they often had no control over. Writing becomes a way for them to exert that control. Danielle Carniaux The Clinton School, grades 9, 12, teaching 8 years, IB Language and Literature This was the first year I integrated third-world feminism into my curriculum on post-colonial literature. It was a challenging and gratifying topic. Students agreed that western feminism (second- and third-wave) didn’t meet the needs of women of the third worlds, but they had a harder time understanding that third-world feminism isn’t just intersectional—it is unique to developing countries and their populations. -

Annual Report 2011 1 LETTER from the EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

“What YCP is doing is truly amazing. It was incredibly rewarding to work in an environment where you understood the near-term impact you were having on so many families. I wish there were more organizations like YCP out there.” - David Saar, Volunteer from PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP Yorkville Common Pantry 2011 Annual Report MISSION STATEMENT Yorkville Common Pantry is dedicated to reducing hunger while promoting dignity and self-sufficiency. YCP champions the cause of the hungry through food pantry and meal distribution programs, nutrition education, basic hygiene services, homeless sup- port, and related services. YCP’s community-based programs focus on East Harlem and other underserved communities throughout New York City. YCP is grateful for our ongoing relationship with our 19 sponsoring organizations that not only provide volunteers, Board members, funds, food and other donations, but further infuse our work with profound meaning and reward. We consider these organiza- tions to be caring members of the extended YCP family, and feel very fortunate to have their dedication and involvement. BOARD OF DIRECTORS SPONSORING ORGANIZATIONS Wendy A. Stein Robert Hetu The Brick Presbyterian Church Chair Lindsay Higgins The Church of the Heavenly Rest Jamie Hirsh The Church of the Holy Trinity Sherrell Andrews Linda E. Holt The Church of St. Edward the Martyr Gerard M. Meistrell Patricia Hughes Church of St. Ignatius Loyola Madeleine Rice Stuart Johnson Church of St. Thomas More Vice Chairs Camille Kelleher Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church Patricia Kelly Park Avenue Christian Church Katherina Grunfeld Susan Kessler Park Avenue Synagogue Secretary Michael Kutch Park Avenue United Methodist Church Kathy A. -

The Rules of #Metoo

University of Chicago Legal Forum Volume 2019 Article 3 2019 The Rules of #MeToo Jessica A. Clarke Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Clarke, Jessica A. (2019) "The Rules of #MeToo," University of Chicago Legal Forum: Vol. 2019 , Article 3. Available at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol2019/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Chicago Legal Forum by an authorized editor of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Rules of #MeToo Jessica A. Clarke† ABSTRACT Two revelations are central to the meaning of the #MeToo movement. First, sexual harassment and assault are ubiquitous. And second, traditional legal procedures have failed to redress these problems. In the absence of effective formal legal pro- cedures, a set of ad hoc processes have emerged for managing claims of sexual har- assment and assault against persons in high-level positions in business, media, and government. This Article sketches out the features of this informal process, in which journalists expose misconduct and employers, voters, audiences, consumers, or professional organizations are called upon to remove the accused from a position of power. Although this process exists largely in the shadow of the law, it has at- tracted criticisms in a legal register. President Trump tapped into a vein of popular backlash against the #MeToo movement in arguing that it is “a very scary time for young men in America” because “somebody could accuse you of something and you’re automatically guilty.” Yet this is not an apt characterization of #MeToo’s paradigm cases. -

Gone Rogue: Time to Reform the Presidential Primary Debates

Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy Discussion Paper Series #D-67, January 2012 Gone Rogue: Time to Reform the Presidential Primary Debates by Mark McKinnon Shorenstein Center Reidy Fellow, Fall 2011 Political Communications Strategist Vice Chairman Hill+Knowlton Strategies Research Assistant: Sacha Feinman © 2012 President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved. How would the course of history been altered had P.T. Barnum moderated the famed Lincoln-Douglas debates in 1858? Today’s ultimate showman and on-again, off-again presidential candidate Donald Trump invited the Republican presidential primary contenders to a debate he planned to moderate and broadcast over the Christmas holidays. One of a record 30 such debates and forums held or scheduled between May 2011 and March 2012, this, more than any of the previous debates, had the potential to be an embarrassing debacle. Trump “could do a lot of damage to somebody,” said Karl Rove, the architect of President George W. Bush’s 2000 and 2004 campaigns, in an interview with Greta Van Susteren of Fox News. “And I suspect it’s not going to be to the candidate that he’s leaning towards. This is a man who says himself that he is going to run— potentially run—for the president of the United States starting next May. Why do we have that person moderating a debate?” 1 Sen. John McCain of Arizona, the 2008 Republican nominee for president, also reacted: “I guarantee you, there are too many debates and we have lost the focus on what the candidates’ vision for America is.. -

New Beacon School Chief on His Way Cell Tower Proposed Off Route 9

[FREE] Serving Philipstown and Beacon Softball Sisters Page 19 JUNE 23, 2017 161 MAIN ST., COLD SPRING, N.Y. | highlandscurrent.com New Beacon School Chief on His Way A Q&A with the 10th He next moved to Charlot- tesville, Virginia, where he superintendent in was an elementary school as many years principal while pursuing advanced degrees in educa- tion administration at the By Jeff Simms University of Virginia. Lan- atthew Landahl, dahl and his family moved hired in January to Ithaca in 2013 when he Mas superintendent was hired as the district’s of the Beacon City School chief elementary schools of- District, will assume the job ficer. In 2014 he became its on July 1. He succeeds Ann chief academic officer. Marie Quartironi, who has Following Walkley’s res- Matthew Landahl been acting as interim su- ignation, the Beacon school File photo by J. Simms perintendent since the con- board hired a search firm, tentious resignation of Bar- which created focus groups bara Walkley in January 2016. Quartironi to compile a “leadership profile” of what will return to her job as the district’s fi- the district and community were looking The Clearwater Festival on June 17 and 18 showcased many roving jugglers, including nance chief. for. Landahl beat out nearly 50 other ap- Allison McDermott. For more festival photos, see Page 15. Photo by Ross Corsair Most recently a deputy superintendent plicants. He spoke with The Current a few for the Ithaca City School District, Lan- days before he was set to move to Beacon. dahl will become the district’s 10th super- His comments have been edited for brevity. -

2018 Fellow Bios

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 2018 Fellow Bios Jonathan Arking is a junior at Beth Tfiloh High school. There, he captains the Model UN and cross- country teams and serves as the head of the school's AIPAC (American Israel Public Affairs Committee) club. In addition, he participates in Mock Trial, NHS, Kolenu (the high school choir), and the ultimate Frisbee team. Outside of school, Jonathan frequently reads the Torah portion and leads the services at Congregation Netivot Shalom, the Modern Orthodox synagogue he and his family founded, and now attend. In his free time, Jonathan loves running, reading, and singing -- especially traditional Jewish songs. He is greatly excited to be a Bronfman Fellow and looks forward to an inspiring and insightful summer. Hannah Bashkow is currently a junior at Tandem Friends School. Before that, she attended the Charlottesville Waldorf School through eighth grade. She and her family are members of Charlottesville’s Congregation Beth Israel, where they regularly attend the Saturday morning traditional egalitarian minyan. At the synagogue, she works as a Hebrew tutor and helps kids prepare for their b’nei mitzvah. She is an enthusiastic artist who enjoys working in many media. In past summers, she has attended Nature Camp, a local field ecology camp, and has traveled with her family to Israel, Europe, and Papua New Guinea. Sarah Bock is a junior at Scarsdale High School and a member of Westchester Reform Temple. At SHS, Sarah is a member of Signifer, which functions as Scarsdale’s Honor Society, as well as a peer tutoring program. She is on the school’s cross country and track teams and is a member of the Pratham club, which raises money to fund women’s education in India. -

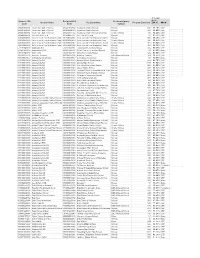

Firstname Lastname Schoolname Workcategory Worktitle Jack Adam NYC Ischool Photography 1962, Escape from Alcatraz Turiya Adkins

FirstName LastName SchoolName WorkCategory WorkTitle Jack Adam NYC iSchool Photography 1962, Escape From Alcatraz Turiya Adkins Saint Ann's School Photography Identity Unseen Turiya Adkins Saint Ann's School Mixed Media Lives Labeled Turiya Adkins Saint Ann's School Mixed Media It's All Lies Darling Turiya Adkins Saint Ann's School Mixed Media Frida Jasmin N. Ali Irwin Altman Middle School 172 Drawing Still Life Jasmin N. Ali Irwin Altman Middle School 172 Painting Dream State P.S. 333 Manhattan School for Zeke Allis Children Comic Art Team M Anzia Anderson Edward R. Murrow High School Mixed Media Betsy Ross Achievement First Brooklyn High Douglas Anderson School Digital Art Equalibrium Anisha Andrews The High School of Fashion Industries Photography Farewell Anisha Andrews The High School of Fashion Industries Photography The Usual Andrea Antomattei High School of Art & Design Drawing Mad With Beauty Andrea Antomattei High School of Art & Design Drawing Banana Phone Andrea Antomattei High School of Art & Design Drawing I Am Not Good Or Bad Camila Arria-maury Convent of the Sacred Heart Photography Technological Coffee Lamia Ateshian Horace Mann School Painting Caged Lamia Ateshian Horace Mann School Drawing View Overlooking Middle School Lamia Ateshian Horace Mann School Painting Fine Eyes Noa Attias Ramaz School Drawing Venetian Triptich Zoe Bank The Chapin School Photography Leafdrop Zoe Bank The Chapin School Photography Rising Above It Theatre Arts Production Company Lorianny Batista School Painting Lorianny Victor Batista Millenium -

CEP May 1 Notification for USDA

40% and Sponsor LEA Recipient LEA Recipient Agency above Sponsor Name Recipient Name Program Enroll Cnt ISP % PROV Code Code Subtype 280201860934 Academy Charter School 280201860934 Academy Charter School School 435 61.15% CEP 280201860934 Academy Charter School 800000084303 Academy Charter School School 605 61.65% CEP 280201860934 Academy Charter School 280202861142 Academy Charter School-Uniondale Charter School 180 72.22% CEP 331400225751 Ach Tov V'Chesed 331400225751 Ach Tov V'Chesed School 91 90.11% CEP 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charte 331300860902 Achievement First Endeavor Charter School 805 54.16% CEP 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charte 800000086469 Achievement First University Prep Charter School 380 54.21% CEP 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charte 332300860912 Achievement First Brownsville Charte Charter School 801 60.92% CEP 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charte 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charter School 393 62.34% CEP 570101040000 Addison CSD 570101040001 Tuscarora Elementary School School 455 46.37% CEP 410401060000 Adirondack CSD 410401060002 West Leyden Elementary School School 139 40.29% None 080101040000 Afton CSD 080101040002 Afton Elementary School School 545 41.65% CEP 332100227202 Ahi Ezer Yeshiva 332100227202 Ahi Ezer Yeshiva BJE Affiliated School 169 71.01% CEP 331500629812 Al Madrasa Al Islamiya 331500629812 Al Madrasa Al Islamiya School 140 68.57% None 010100010000 Albany City SD 010100010023 Albany School Of Humanities School 554 46.75% CEP 010100010000 Albany -

Bro, Foe, Or Ally? Measuring Ambivalent Sexism in Political Online Reporters

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by City Research Online Bro, foe, or ally? Measuring ambivalent sexism in political online reporters Lindsey E. Blumell Department of Journalism, City, University of London, London, UK ABSTRACT The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (ASI) measures hostile (overt antagonism towards women) and benevolent (chivalry) sexism. Previous research shows that political ideology contributes to ASI. Yet little attention has been given to increasingly popular political websites in terms of measuring sexism. Furthermore, recent firings of news professionals over accused sexual misconduct reveal the seriousness of sexism in the news industry. This study surveyed political online reporters (N = 210) using ASI and predicting sociodemographic and organizational factors. Results show benevolent sexism levels mostly similar for all factors, but not hostile sexism. Those working for conservative websites had higher levels of hostile sexism, but website partisanship had no significance for benevolent sexism. Men reported higher levels of hostile sexism and protective paternalism, but not complementary gender differentiation. Overall, individual levels of conservatism also predicted hostile sexism, but not benevolence. The pervasiveness of benevolence jeopardizes women’s progression in the workplace. High levels of hostility ultimately endanger newsrooms, as well as negatively impact political coverage of gender related issues. “Can I have some of the queen’s waters? Precious waters? Where’s that Bill Cosby pill I brought with me?” laughed veteran MSNBC host Chris Matthews, moments before interviewing the soon to be first female major party presidential candidate in US history (Noreen Malone 2018). His off-the-cuff remarks (1) belittled the authority of Hillary Clinton (calling her a queen) and (2) included a “joke” about giving her a Quaalude (Cosby has admitted to giving women Quaaludes in order to have sexual intercourse; Graham Bowley and Sydney Ember [2015]). -

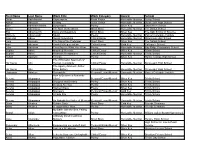

First Name Last Name Work Title Work Category Award School

First Name Last Name Work Title Work Category Award School Omar Abdelhamid Skyscrapers Flash Fiction Honorable Mention Trinity School Adrian Aboyoun Driving Flash Fiction Honorable Mention Stuyvesant High School Edie Abraham-Macht Suspended Poetry Silver Key Saint Ann's School Grace Abrahams The Man on the Street Short Story Honorable Mention The Dalton School Etai Abramovich Sons and Daughters Short Story Silver Key The Salk School of Science Michelle Abramowitz Squid Poetry Honorable Mention Packer Collegiate Institute Diamond Abreu Social Networking Critical Essay Honorable Mention Millennium High School Lucy Ackman The Day of the Professor Short Story Silver Key The Dalton School max adelman Hamlet's Regeneration Critical Essay Gold Key Collegiate School Lebe Adelman They Say It’s What You Wear Poetry Honorable Mention Bay Ridge Preparatory School Sophia Africk Morphed Mercutio Critical Essay Silver Key Trinity School Sophia Africk Richard's Realizations Critical Essay Honorable Mention Trinity School Rohan Agarwal Friends Poetry Silver Key Hunter College High School The Whitmanic Spectrum of Ha Young Ahn Human Immortality Critical Essay Honorable Mention Stuyvesant High School The Agency Moment: Arthur Ha Young Ahn Miller Edition Critical Essay Honorable Mention Stuyvesant High School Hadassah Akinleye Second Air Personal Essay/Memoir Honorable Mention Packer Collegiate Institute How to Become a Romantic Serena Alagappan Cliché Personal Essay/Memoir Silver Key Trinity School Serena Alagappan Drugged and Dreamy Poetry Silver Key Trinity -

Silver Key Winners

Silver Key Winners Name School Genre Title Tyra Abraham Hewitt School Photography Drops Of Life Silver Key Tyra Abraham Hewitt School Photography Vulnerability Silver Key Tyra Abraham Hewitt School Photography Martha Silver Key Emily Acquista Art and Design High School Drawing Journey To The Bridge (of The Nose) Silver Key Emily Acquista Art and Design High School Drawing Nude of Many Colors Silver Key Emily Acquista Art and Design High School Drawing Ellis Silver Key Jack Adam MS 51 William Alexander Photography Hail Silver Key Jack Adam MS 51 William Alexander Photography Gabrielle Silver Key Oliver Agger Saint Ann's School Photography Marfa Silver Key Michael Aguero-sinclair The Dalton School Photography Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary Silver Key Jinah Ahn Ashcan Studio of Art Sculpture Brace Face Silver Key Esther An Ashcan Studio of Art Drawing Glare Silver Key Anahi Andrade High School of Art & Design Painting Self-portrait Silver Key Carolina Aparicio P.S. 161 Pedro Albizu Campos Drawing Desert Silver Key Tamar Ashdot-Bari Fiorello H Laguardia High School of Music Photography At The Edge Of The Desert, Before Sunrise Silver Key Rebecca Aydin Hewitt School Mixed Media Fundamental Building Blocks Of Marriage Silver Key Micaela Bahn Writopia Lab Photography Animal Farm Silver Key Jane Baldwin Trinity School Digital Art Lights Silver Key Valeryia Baravik Tottenville High School Photography Pensive Silver Key Sabrina Barrett Bard High School Early College II Photography Simone In The Fields Silver Key Anna Bida Art and Design High School -

My Name Is Leonie Haimson

This letter, written by Class Size Matters and Advocates for Children in Feb. 2004, protesting the Mayor’s proposal to hold back students on the basis of their test scores was signed by 107 eminent academics, researchers, and national experts on testing who say that such a policy is unfair and unreliable, and is likely to lead to lower achievement and higher drop out rates.1 The signers included four past presidents of the American Education Research Association, the nation’s premier organization of educational researchers, as well as the chair of the National Academy of Sciences Committee on the Appropriate Use of Educational Testing, and several members of the Board on Testing and Assessment of the National Research Council. Signers also included Dr. T. Berry Brazelton, renowned pediatrician and author of numerous works on child care and development, Robert Tobias, former head of Division of Assessment and Accountability for the Board of Education and now Director of the Center for Research on Teaching and Learning at NYU, and Dr. Ernest House, who did the independent evaluation of New York City’s failed “Gates” retention program in the 1980’s. Even the two companies that produce the third grade tests are on record that a decision to hold back a child should never be based upon test scores alone. February 11, 2004 Dear Mayor Bloomberg and Chancellor Klein: We ask that you reconsider and withdraw your proposal to retain 3rd grade students on the basis of test scores. All of the major educational research and testing organizations oppose using test results as the sole criterion for advancement or retention, since judging a particular student on the basis of a single exam is an inherently unreliable and an unfair measure of his or her actual level of achievement.