My Name Is Leonie Haimson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

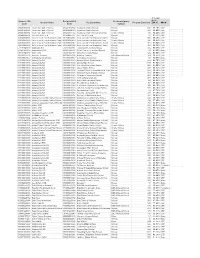

CEP May 1 Notification for USDA

40% and Sponsor LEA Recipient LEA Recipient Agency above Sponsor Name Recipient Name Program Enroll Cnt ISP % PROV Code Code Subtype 280201860934 Academy Charter School 280201860934 Academy Charter School School 435 61.15% CEP 280201860934 Academy Charter School 800000084303 Academy Charter School School 605 61.65% CEP 280201860934 Academy Charter School 280202861142 Academy Charter School-Uniondale Charter School 180 72.22% CEP 331400225751 Ach Tov V'Chesed 331400225751 Ach Tov V'Chesed School 91 90.11% CEP 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charte 331300860902 Achievement First Endeavor Charter School 805 54.16% CEP 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charte 800000086469 Achievement First University Prep Charter School 380 54.21% CEP 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charte 332300860912 Achievement First Brownsville Charte Charter School 801 60.92% CEP 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charte 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charter School 393 62.34% CEP 570101040000 Addison CSD 570101040001 Tuscarora Elementary School School 455 46.37% CEP 410401060000 Adirondack CSD 410401060002 West Leyden Elementary School School 139 40.29% None 080101040000 Afton CSD 080101040002 Afton Elementary School School 545 41.65% CEP 332100227202 Ahi Ezer Yeshiva 332100227202 Ahi Ezer Yeshiva BJE Affiliated School 169 71.01% CEP 331500629812 Al Madrasa Al Islamiya 331500629812 Al Madrasa Al Islamiya School 140 68.57% None 010100010000 Albany City SD 010100010023 Albany School Of Humanities School 554 46.75% CEP 010100010000 Albany -

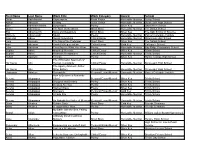

First Name Last Name Work Title Work Category Award School

First Name Last Name Work Title Work Category Award School Omar Abdelhamid Skyscrapers Flash Fiction Honorable Mention Trinity School Adrian Aboyoun Driving Flash Fiction Honorable Mention Stuyvesant High School Edie Abraham-Macht Suspended Poetry Silver Key Saint Ann's School Grace Abrahams The Man on the Street Short Story Honorable Mention The Dalton School Etai Abramovich Sons and Daughters Short Story Silver Key The Salk School of Science Michelle Abramowitz Squid Poetry Honorable Mention Packer Collegiate Institute Diamond Abreu Social Networking Critical Essay Honorable Mention Millennium High School Lucy Ackman The Day of the Professor Short Story Silver Key The Dalton School max adelman Hamlet's Regeneration Critical Essay Gold Key Collegiate School Lebe Adelman They Say It’s What You Wear Poetry Honorable Mention Bay Ridge Preparatory School Sophia Africk Morphed Mercutio Critical Essay Silver Key Trinity School Sophia Africk Richard's Realizations Critical Essay Honorable Mention Trinity School Rohan Agarwal Friends Poetry Silver Key Hunter College High School The Whitmanic Spectrum of Ha Young Ahn Human Immortality Critical Essay Honorable Mention Stuyvesant High School The Agency Moment: Arthur Ha Young Ahn Miller Edition Critical Essay Honorable Mention Stuyvesant High School Hadassah Akinleye Second Air Personal Essay/Memoir Honorable Mention Packer Collegiate Institute How to Become a Romantic Serena Alagappan Cliché Personal Essay/Memoir Silver Key Trinity School Serena Alagappan Drugged and Dreamy Poetry Silver Key Trinity -

Application, Admission, and Matriculation to New York City's

PATHWAYS TO AN ELITE EDUCATION: APPLICATION, ADMISSION, AND MATRICULATION TO NEW YORK CITY’S SPECIALIZED HIGH SCHOOLS Sean Patrick Corcoran Abstract (corresponding author) New York City’s public specialized high schools have a long Steinhardt School of Culture, history of offering a rigorous, college preparatory education Education, and Human to the city’s most academically talented students. Though im- Development mensely popular and highly selective, their policy of admitting New York University students using a single entrance exam has raised questions about New York, NY 10003 diversity and equity in access. In this paper, we provide a de- scriptive analysis of the “pipeline” from middle school to ma- [email protected] triculation at a specialized high school, identifying group-level differences in application, admission, and enrollment. In doing E. Christine Baker-Smith so, we highlight potential points of intervention to improve ac- Steinhardt School of Culture, cess for underrepresented groups. Controlling for other measures Education, and Human of prior achievement, we find black, Hispanic, low-income, and Development female students are significantly less likely to qualify for admis- New York University sion to a specialized high school. Differences in application and New York, NY 10003 matriculation rates also affect the diversity in these schools, and christine.baker-smith@nyu we find evidence of middle school “effects” on both application .edu and admission. Simulated policies that offer admissions using alternative measures, such as state test scores and grades, sug- gest many more girls, Hispanics, and white students would be admitted under these alternatives. They would not, however, ap- preciably increase the share of offers given to black or low-income students. -

Stuyvesant High School Faculty Email Addresses

STUYVESANT HIGH SCHOOL FACULTY EMAIL ADDRESSES FIRST LAST DEPARTMENT EMAIL ADDRESS Natalie Acevedo Secretary [email protected] Ulugbek Akhmedov Physics [email protected] Frida Ambia Language [email protected] Sushma Arora Chemistry [email protected] Marvin Autry Physical Education [email protected] John Avallone Physics [email protected] Deena Avigdor Mathematics [email protected] Perry Badgley Social Studies [email protected] Shangaza Banfield Biology [email protected] Howard Barbin Physical Education [email protected] Susan Barrow Art [email protected] Zachary Berman Social Studies [email protected] Leslie Bernstein Technology [email protected] Joseph Blay Technology [email protected] Harvey Blumm Internships Coord. [email protected] W illiam Boericke Social Studies [email protected] Peter Bologna Physical Education [email protected] Christopher Bowlin Librarian [email protected] Sandra Brandan Guidance [email protected] Lee Brando Social Studies [email protected] Carlos Bravo Language [email protected] Susan Brockman Language [email protected] Peter Brooks Computer Science [email protected] Christopher Brown Mykolyk Computer Science [email protected] Aurea Bullock Health Aide [email protected] Devon Butler Mathematics [email protected] Theresa Bynum Support [email protected] Stephen Cardella Lab Specilist [email protected] Carol Carrano Secretary [email protected] -

Stuyvesant High School Parents' Association

Stuyvesant High School Parents' Association Executive Board of the Stuyvesant High School Parents’ Association December 2018 Statement Regarding Proposed Changes to New York City Specialized High School Admissions 1) An intense debate has been taking place since the referral to the floor of the New York State Legislature in June 2018 of a bill (A10427A/S08503-A)1 that would change the admissions process for New York City’s specialized high schools by amending the section of the New York State Education Law (§2590G, Subdivision 12) that is commonly referred to as the “Hecht-Calandra Act.”2 Under the proposed legislation, for which the stated purpose is increased diversity in the specialized high schools, the Specialized High School Admissions Test (SHSAT) would be phased out entirely over a period of three years as the means of admitting applicants to the specialized high schools and would be replaced by an admissions process that would make offers to the top 7% of students from each New York City public middle school.3 2) The Executive Board of the Stuyvesant High School Parents’ Association recognizes and respects the strongly held opinions that accompany this debate on all sides of the discussion. We support the goal of expanded diversity at Stuyvesant and the other specialized high schools, including increasing Black and Latino/a enrollment. However, we oppose Bill A10427A/S08503-A as a means to accomplish that goal, based on concerns that have been raised as part of the public discussion. We support an admissions process for New York City’s specialized high schools that is fully objective and transparent, that ensures fair and equitable treatment of all New York City students, and that enables those schools to maintain the academic standards and successes that characterize them today. -

First Name Last Name Work Title Work Category Award School

First Name Last Name Work Title Work Category Award School Billie fabrikant Weird in the Ward Poetry Honorable Mention The Dalton School Billie fabrikant Homecoming Short Story Silver Key The Dalton School Scott Fairbanks All the Small Things Personal Essay/Memoir Gold Key Stuyvesant High School Brooklyn Heights Montessori Julia Falcinelli Well, Mr. Lane Flash Fiction Honorable Mention School Anna Farber Elementary Personal Essay/Memoir Honorable Mention Hunter College High School Anna Farber Doubts, I Guess Personal Essay/Memoir Honorable Mention Hunter College High School Charlotte FE On a Wretched Sunny Sunday Poetry Gold Key Saint Ann's School The Unprecedented Destruction of You Collegiate Institute of Math and Jodi-Ann Fearon + I Poetry Silver Key Science June Fergus Simone's Dystopia Science Fiction/Fantasy Honorable Mention The Berkeley Carroll School During, The Aftermath, Initial Voice of Chanelle Ferguson the Soul Poetry Honorable Mention Herbert H Lehman High School Not Exactly Something You Can Put on Cristina Fernandez a Resume Science Fiction/Fantasy Honorable Mention Convent of the Sacred Heart Madison Fernandez The Saddest Flowers Short Story Silver Key Bard High School Early College Samantha Fierro It girl + reality Personal Essay/Memoir Honorable Mention Eleanor Roosevelt High School Hannah Finamore-Rossler Shayna Kopf Dramatic Script Silver Key Saint Ann's School Hannah Finamore-Rossler Lakeview Shock Correctional Poetry Honorable Mention Saint Ann's School Hannah Finamore-Rossler Frankie the Worm Short Story Honorable -

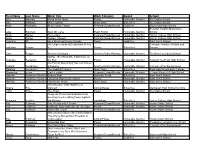

2015 NYC Writing Recipients — SCHOOLS

School Educator First Educator Last First Name Last Name Awards Category Title - Katia Belousova Leo Lion Gold Key Flash Fiction Old News - Katia Belousova Leo Lion Honorable Mention Dramatic Script Before Barnaby (No Tears) - Katia Belousova Leo Lion Honorable Mention Dramatic Script The Internet Island Project - Katia Belousova Leo Lion Silver Key Poetry Prison of Rhyme - Katia Belousova Leo Lion Honorable Mention Science Fiction/Fantasy Duplicate Incubation Facility Protocol - Katia Belousova Leo Lion Honorable Mention Dramatic Script Ties - Phoenix Ford Nkosi Nkululeko Silver Key Poetry It's Something Almost Like A Gift - J.e. Franklin Nkosi Nkululeko Gold Key, American Poetry The Gone Game Voices Nominee - J.e. Franklin Nkosi Nkululeko Silver Key Poetry It's Something Almost Like A Gift - Ayun Halliday Milo Kotis Gold Key Dramatic Script The Cockroach and the Cage - Ayun Halliday Milo Kotis Honorable Mention Critical Essay The Graphic Novelologist - William Heagy David Heagy Gold Key Critical Essay Elephants in the Room - Anna Lis Anna Lis Gold Key Personal Essay/Memoir Musings of a Malnourished Mind - nadia pushkina Emily Mondrus Honorable Mention Poetry Leaving a Mark - Kim Smith Dan R. Allen Honorable Mention Dramatic Script Stories - Kim Smith Dan R. Allen Honorable Mention Flash Fiction The Stranger A Philip Randolph Campus Elizabeth Decker Mariam kamate Silver Key Poetry Here's to all the girls like High School Abraham Joshua Heschel Karen Dorr Livia Miller Silver Key Personal Essay/Memoir Family China High School Abraham Joshua -

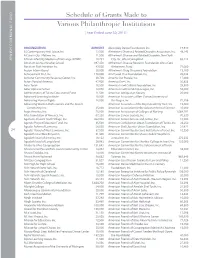

Schedule of Grants Made to Various

Schedule of Grants Made to Various Philanthropic Institutions [ Year Ended June 30, 2015 ] ORGANIZATION AMOUNT Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc. 19,930 3S Contemporary Arts Space, Inc. 12,500 Alzheimer’s Disease & Related Disorders Association, Inc. 46,245 A Cure in Our Lifetime, Inc. 11,500 Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders, New York A Torah Infertility Medium of Exchange (ATIME) 20,731 City, Inc. d/b/a CaringKind 65,215 Abraham Joshua Heschel School 397,450 Alzheimer’s Disease Research Foundation d/b/a Cure JEWISH COMMUNAL FUND JEWISH COMMUNAL Abraham Path Initiative, Inc. 42,500 Alzheimer’s Fund 71,000 Accion International 30,000 Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation 15,100 Achievement First, Inc. 170,000 Am Yisroel Chai Foundation, Inc. 25,036 Achiezer Community Resource Center, Inc. 20,728 Ameinu Our People, Inc. 17,000 Actors Fund of America 47,900 America Gives, Inc. 30,856 Adas Torah 16,500 America-Israel Cultural Foundation, Inc. 25,500 Adler Aphasia Center 14,050 America-Israel Friendship League, Inc. 55,000 Administrators of Tulane Educational Fund 11,500 American Antiquarian Society 25,000 Advanced Learning Institute 10,000 American Associates of Ben-Gurion University of Advancing Human Rights 18,000 the Negev, Inc. 71,386 Advancing Women Professionals and the Jewish American Associates of the Royal Academy Trust, Inc. 15,000 Community, Inc. 25,000 American Association for the Advancement of Science 35,000 Aegis America, Inc. 75,000 American Association of Colleges of Nursing 1,064,797 Afya Foundation of America, Inc. 67,250 American Cancer Society, Inc. -

Ups and Down…

PATHWAYS NEWSLETTER VOL 2_2012 7/9/12 1:26 PM Page 1 RABBI ARTHUR SCHNEIER PARK EAST DAY SCHOOL We Did it Again: This Year’s Awards Some Important Rabbi Arthur Schneier Park East Day School is thrilled to congratulate our students Dates to Remember on this year’s achievements in math, science and technology. Our young scholars September 6 Grades 1-8 were recognized with the following awards: First Session New York Mathematics League September 7 K, Nursery 4, Older 3s 6th Grade Ranked #1 in the New York City Region First Session Derek Korff-Korn, Aaron Samekhov, and Sara Serfaty, Ranked #3 Pathways September 10 Nursery 2, Trans. 3s SUMMER 2012 | VOLUME 2 | 5772 7th Grade Ranked #3 in the New York City Region First Session Ephraim Kozodoy-Ranked #1 in New York State September 17 & 18 Rosh Hashanah Michael Weisberg-Ranked #4 in the New York City Region School Closed 8th Grade Ranked #1 in the New York City Region September 25 & 26 Yom Kippur Noam Kaplan and Mindy Kristt- Ranked #1 in New York City Region School Closed American Math Competition 2011-2012 October 1 & 2 Succot Top 1% Noam Kaplan School Closed Top 5% Aviel Kaplan, Ephraim Kozodoy, Mindy Kristt, Coby Rem, Aidan Smolar, and October 8 Shemini Atzeret Michael Weisberg School Closed Ups and Down… CIJE (Center for Initiative in Jewish Education)-Virtual Math Competition October 9 Simchat Torah 7th Grade Ranked #1 8th Grade Ranked #3 School Closed No Longer Unpredictable November 22 & 23 Thanksgiving STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Math)-Interschool Competition School Closed It is with great joy that we report that Park East Day School has Park East Day School Ranked #1. -

Policy Statement from the Coalition of Specialized High Schools Alumni Organizations

POLICY STATEMENT FROM THE COALITION OF SPECIALIZED HIGH SCHOOLS ALUMNI ORGANIZATIONS BRONX SCIENCE ALUMNI FOUNDATION BROOKLYN TECH ALUMNI FOUNDATION SITHS ALUMNI ASSOCIATION, INC. STUYVESANT HIGH SCHOOL ALUMNI ASSOCIATION April 2019 The Bronx Science Alumni Foundation, Brooklyn Tech Alumni Foundation, Staten Island Technical High School Alumni Association and Stuyvesant High School Alumni Association believe in the importance of a specialized high school education and want to ensure that it is preserved for future generations. We also value diversity and strongly believe that much can – and must – be done to increase diversity in these schools. However, we do not believe that eliminating the Specialized High Schools Admissions Test (SHSAT) as the sole criteria for admissions and replacing it with alternative admissions mechanisms is the answer to the much larger problems facing New York City and its educational system. Furthermore, in a New York City public education system with 130 other options for high-achieving students from across the five boroughs, there is a valuable role for 8 specialized high schools to play. As legislators and policy makers on the State and City levels convene a series of hearings, roundtables and discussions in the coming months, the members of the Coalition of Specialized High School Organizations look forward to participating in the dialogue and offering our input on both the root causes of this problematic lack of diversity and, more importantly, potential solutions. THE REAL ISSUE The purpose of having the SHSAT is to permit every child an equal opportunity to gain admission to a specialized high school regardless of race or ethnicity and without favoritism. -

New York City's Children First

AP PHOTO/MARK LENNIHAN PHOTO/MARK AP New York City’s Children First Lessons in School Reform By Maureen Kelleher January 2014 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG New York City’s Children First Lessons in School Reform By Maureen Kelleher January 2014 Contents 1 Introduction and summary 11 NYC’s reforms and district performance in the Bloomberg years 19 Remaking the district: Mayoral control, school autonomy, and accountability 27 Remaking the schools: Small schools, choice, closures, and charters 35 Remaking the budget: Focus on equity 41 Remaking the workforce: Developing talent in local context 51 Conclusion and recommendations 57 Endnotes Introduction and summary Under Mayor Michael Bloomberg, New York City’s education system embarked on a massive change effort, known as Children First, that produced significant results: new and better school options for families, more college-ready gradu- ates, and renewed public confidence in New York City’s schools. New York City’s reform effort has also produced significant change beyond the city’s own schools and has helped to set a national agenda for reforming education. Over the past 12 years, other districts, especially in large urban centers, have looked to New York City for ideas as they work to improve outcomes for their students. New York City’s central administrators have also gone on to lead districts elsewhere in the nation, spreading not just particular reform strategies but also a mindset focused on bold and rapid system change to improve student achievement. This report tells the story of how Children First reforms evolved over the course of Bloomberg’s mayoralty and synthesizes research on the effectiveness of those reforms. -

The World School • Bard High School Early College

Class of 2015 High School Acceptances • A venues: The World School • Bard High School Early College Manhattan • Bard High School Early College Queens • Berkeley Carroll School • Brooklyn Friends School • Brooklyn Technical High School • Chapin School • Choate Rosemary Hall • Dwight School • Eleanor Roosevelt High School • Elisabeth Irwin • E l t h o i o c a h c l S C u y r l t o u t r a e r a F p i e e l r d P Berkeley Carroll School s t k o r Loyola School n o Y S • c h l o o Ethical Culture Fieldston School o o h l c • S Brooklyn Friends School F h Ross School Bard High School Early College Queens i o g i r e H l r l o e i H v . a L X a • G l u o a o r h d c Fordham Preparatory School Friends Seminary i S a l Trinity School H a i n g o h i t S a c n h r o e t Horace Mann School o n l I o s f n Elisabeth Irwin M o i u t a Dwight School s i N c & d e A t i r n t e Beacon School U a n • l d o P o Packer Collegiate Institute e h r c f S o r y m t i n Milton Academy i i n r g T A • l Eleanor Roosevelt High School r t o s o • h c F S o r y d a h D Eleanor Roosevelt High School a r m o v P e Poly Prep Country Day School r r e T p • a l r o a o t o h c r y S t S i Saint Ann’s c h m Bard High School Early College Manhattan o m o u l S • e F h r T i e • n l d o s o S h e Bronx High School of Science e c Xavier High School m S d i n r a o f r y m • a B G - r e Léman Manhattan Preparatory School a l c a e g Trevor Day School n C i h t u h r g i c h N S e c h h T Riverdale Country School o • o l l o • o Grace Church School H h Brooklyn Technical High School York Preparatory School c a S r Choate Rosemary Hall v s r e e s t t s C a o M l l e e g h T i The Loomis Chaffee School New York City Lab School for Collaborative Studies a • t l e o H o i h g c h S S e c e h o a o h l C • s Regis High School i The Nightingale-Bamford School H o m r o a o c L e e M h a T n • n l o The Summit School S o c h h United Nations International School c o S o l n • u o K h e l n a Rudolf Steiner School t C S e Harvest Collegiate High School Fiorello H.