Application, Admission, and Matriculation to New York City's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harvard University

The Peck School CORNELL UNIVERSITY Colleges and Number of Attendees 2011-2015 Northeastern Harvard University 9 Johns Hopkins University 3 University University Villanova University 9 University of Delaware 3 Boston College 8 University of Richmond 3 of Pennsylvania of University Lafayette College 6 Yale University 3 Princeton University 6 Boston University 2 Colorado Boulder Colorado University of Pennsylvania 6 Emory University 2 Johns Hopkins University Dame Notre of University Duke University 5 Gettysburg University 2 Stanford University New York University 5 Lehigh University 2 Lafayette College Washington & Lee University 5 Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2 Brown University 4 Northeastern University 2 Lehigh Bowdoin College University Dartmouth College 4 Stanford University 2 Connecticut College Georgetown University 4 Syracuse University 2 Middlebury College 4 University of Colorado Boulder 2 of Technology Massachusetts Institute Southern Methodist University 4 University of Michigan 2 Dartmouth Colby College 3 University of Notre Dame 2 Colgate University 3 University of St. Andrews, Scotland 2 Fairfield University 3 Vanderbilt University 2 Gettysburg University Gettysburg College DELIVERING Wesleyan University Bowdoin College, Bryant University, Bryn Mawr College, College of Charleston, on the Syracuse University Syracuse College of the Holy Cross, Connecticut College, Cooper Union, Cornell University, Denison University, Dickinson College, Elon University, Fordham University, promise University of Franklin & Marshall College, -

Sociology & Anthropology

SOCIOLOGY & | ANTHROPOLOGY NYC FACULTY Ida Dupont (PhD in Criminal Justice, City University of New York). Professor Dupont’s research and teaching interests focus on gender, crime and violence, and structures of the family. Amy Foerster (PhD in Sociology, Cornell University). Professor Foerster’s The Sociology and Anthropology department on Pace University’s New York City research and teaching interests focus campus offers a combined Bachelor of Arts degree in Sociology/Anthropology, as on immigration, popular culture well as a minor. The minor is offered on both New York City and Pleasantville campuses. and the sociology of organizations. Judith Pajo (PhD in Anthropology, Sociology is the study of the impact of structural and cultural forces upon individuals University of California, Irvine). and groups in contemporary society. Anthropology is the ethnographic, holistic and Professor Pajo’s research and teaching comparative study of one’s own society and that of other societies throughout the interests focus on environmental world. The disciplines of sociology and anthropology have many commonalities: anthropology, the anthropology of both investigate the social world we inhabit and explain how human behaviors Europe, and political and economic relate to culture and society. Once limited to the study of small-scale communities in anthropology. non-industrial societies, the field of anthropology has expanded its scope to now include a variety of communities and cultures such as ethnic groups in the Roger Salerno (PhD in Sociology, United States, factory workers in Europe, brokers on Wall Street, indigenous New York University). Professor Salerno’s research and teaching groups in South America, and tribes in the Kalahari desert. -

New York University Bulletin

New York University Bulletin Steinhardt School of Culture, Education and Human Development New York University Washington Square New York, New York 10003 NOTICES About this Bulletin The policies, requirements, course offerings, schedules, activities, tuition, fees, and calendar of the school and its departments and programs set forth in this bulletin are subject to change without notice at any time at the sole discretion of the administration. Such changes may be of any nature, including, but not limited to, the elimination of the school or college, programs, classes, or activities; the relocation of or modification of the content of any of the foregoing; and the cancellation of scheduled classes or other academic activities. Payment of tuition or attendance at any classes shall constitute a student’s acceptance of the administration ‘s rights as set forth herein. Fieldwork Placement Advisory Be advised that fieldwork placement facilities that provide training required for your program degree, and agencies that issue licenses for practice in your field of study, each may require you to undergo general and criminal background checks, the results of which the facility or agency must find accept able before it will allow you to train at its facility or issue you a license. You should inform yourself of offenses or other facts that may prevent you from obtaining a license to practice in your field of study. NYU Steinhardt will not be responsible if you are unable to complete program requirements or cannot obtain a license to practice in your field because of the results of such background checks. Some fieldwork placement facilities in your field of study may not be available to you in some states due to local legal prohibitions. -

Upper School Programs About Prepare Inc

UPPER SCHOOL PROGRAMS ABOUT PREPARE INC. Prepare Inc. is an educational services company that offers comprehensive violence prevention programs and evidence-based programs for personal safety, communication skills, and self-defense. Our school programs are designed to empower students and improve their safety and well-being by simultaneously lowering risk factors and raising protective factors. Prepare is recognized for its ability to communicate with young people and tailor its programs to always be age-appropriate. Since 1992, Prepare Inc. has served over 30,000 young people and adults and provided programs and trainings for over 30 K-12 schools. 9TH -12TH GRADE PROGRAMS Prepare Inc. offers the following programs for Upper School students: • Personal Safety • Healthy Relationships • Health Education Improving the safety of young people is a community- wide effort. Therefore, we highly recommend combining one or more of these programs with the Parent, Caregiver, and Educator Workshop. The workshop encourages and multiplies a community of positive adult role models who are able to reinforce the lessons learned. PREPARE Personal Safety Can students anticipate problems and take actions to avoid danger? Can they use communication skills to clearly set boundaries in friendships and romantic Violence Prevention relationships? Can they resist physical aggression and find safety? The young people you care about need life skills that will help them stay safer. The program provides teens (Grades 8-12) with age-appropriate, com- prehensive, violence prevention education, including personal safety, Healthy Boundaries self-advocacy, and self-reliance. Students learn to distinguish between instincts and bias when assessing threats to their safety. We emphasize the importance of de-escalating situations. -

The NYC RBE-RN @ Fordham University the New York City Regional Bilingual & Education Resource Network

Graduate School of Education, James J. Hennessy, Ph.D., Dean Center for Educational Partnerships, Anita Vazquez Batisti, Ph.D. Associate Dean/Director The NYC RBE-RN @ Fordham University Fall 2014 The New York City Inside this issue: Regional Bilingual & Education Resource Network Message from Dr. Anita Batisti …………….….p.2 Creating an Environment that Embraces All The NYC RBE-RN at Fordham University welcomes you to Students by Eva Garcia ……………………..…. p.3 the 2014-2015 school year. We are continuing this year with the NY State News: Amendments to Part 154 Collaborative Accountability Initiative to support schools in creat- by Bernice Moro…………..…………….……. p.4 ing professional learning communities centered on the education of The Power of Non-Fiction English language learners. Along with this initiative we will continue by Diane Howitt ……. ………………..…….... p.5 with Regional Professional Development to be offered in the form Talk is the Seed From Which All Writing of institutes, clinics and symposia. Each of the 2014-2015 sessions Germinates by Sara Martinez …………..…..…. p.7 will be dedicated to the alignment of Common Core Learning “Get the Gist”: A Summary Strategy to Improve Standards for English language learners. ……… Reading Comprehension by Aileen Colón…........p.9 Our newsletters will continue quarterly beginning with the cur- ELLs Can Write Using the Writing Process rent RBE-RN Fall Newsletter that focuses on developing reading by Elsie Cardona-Berardinelli ……….…..…. p.11 and writing skills using nonfiction texts. In the articles that follow, Using the Language Frames “Hidden” Behind you will find research-based strategies about how nonfiction texts the Text by Roser Salavert …………..……….p.13 can be incorporated into the lessons to scaffold the learning pro- The Fordham University Dual Language cess of ELL students. -

Joe Salvatore

JOE SALVATORE Program in Educational Theatre • Department of Music and Performing Arts Professions Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development New York University, 82 Washington Square East, Pless Annex, Room 223, New York, NY 10003 Phone: (212) 998-5266 • Fax: (212) 995-4569 • E-mail: [email protected] www.joesalvatore.com EDUCATION University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA. M.F.A., Dramaturgy / Directing. May 1998. Thesis Topic: “Quinceañera: A Collaborative Workshop Production.” University of Delaware, Newark, DE. Honors B.A., History, May 1995. Honors Thesis Topic: “Bertolt Brecht’s Success in Exile: November 1938 to May 1940.” ACADEMIC POSITIONS Clinical Associate Professor of Educational Theatre, Department of Music and Performing Arts Professions, Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development, New York University, September 2014-Present. Clinical Assistant Professor of Educational Theatre, Department of Music and Performing Arts Professions, Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development, New York University, September 2011-August 2014. Master Teacher of Educational Theatre, Department of Music and Performing Arts Professions, Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development, New York University, September 2003-August 2011. Faculty Fellow in Residence, Office of Residential Life and Housing Services, New York University, 2005-2014. Instructor, Pre-College Program, Barnard College, June-July 2003. Adjunct Instructor, Program in Educational Theatre, Department of Music and Performing Arts Professions, Steinhardt School of Education, New York University, 2002-2003. Associate Adjunct Professor, Department of Communication Studies, Performance Studies, and Theatre, Long Island University, Brooklyn Campus, 2001-2003. Instructor, Department of Theater, University of Massachusetts-Amherst, 1997-1999. Teaching Assistant, Department of Theater, University of Massachusetts-Amherst, 1995-1997. -

CEP May 1 Notification for USDA

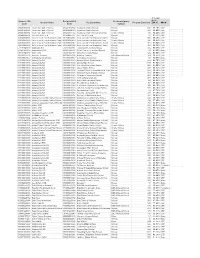

40% and Sponsor LEA Recipient LEA Recipient Agency above Sponsor Name Recipient Name Program Enroll Cnt ISP % PROV Code Code Subtype 280201860934 Academy Charter School 280201860934 Academy Charter School School 435 61.15% CEP 280201860934 Academy Charter School 800000084303 Academy Charter School School 605 61.65% CEP 280201860934 Academy Charter School 280202861142 Academy Charter School-Uniondale Charter School 180 72.22% CEP 331400225751 Ach Tov V'Chesed 331400225751 Ach Tov V'Chesed School 91 90.11% CEP 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charte 331300860902 Achievement First Endeavor Charter School 805 54.16% CEP 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charte 800000086469 Achievement First University Prep Charter School 380 54.21% CEP 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charte 332300860912 Achievement First Brownsville Charte Charter School 801 60.92% CEP 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charte 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charter School 393 62.34% CEP 570101040000 Addison CSD 570101040001 Tuscarora Elementary School School 455 46.37% CEP 410401060000 Adirondack CSD 410401060002 West Leyden Elementary School School 139 40.29% None 080101040000 Afton CSD 080101040002 Afton Elementary School School 545 41.65% CEP 332100227202 Ahi Ezer Yeshiva 332100227202 Ahi Ezer Yeshiva BJE Affiliated School 169 71.01% CEP 331500629812 Al Madrasa Al Islamiya 331500629812 Al Madrasa Al Islamiya School 140 68.57% None 010100010000 Albany City SD 010100010023 Albany School Of Humanities School 554 46.75% CEP 010100010000 Albany -

Recent Senior Administrative Searches

RECENT SENIOR ADMINISTRATIVE SEARCHES This sampling of recent senior administrative searches illustrates the broad range of schools we serve and the strength of their appointees. ETHICAL CULTURE FIELDSTON SCHOOL NEW YORK, NY (2018-19) Since its founding in 1878, Ethical Culture Fieldston School has been a beacon of progressive education in America. Known among New York City independent schools as a place where children are simultaneously encouraged to revel in the joys of childhood and confront the challenges presented by the modern world, ECFS emphasizes ethical thinking, academic excellence, and student-centered learning. PRINCIPAL, FIELDSTON UPPER - Nigel Furlonge was Associate Head of School at Holderness School from 2015-2018 before his appointment at ECFS. Previous posts include Admissions Director and Dean of Students and Residential Life at Christina Seix Academy, Academic Dean at The Lawrenceville School, and Director of Studies at St. Andrew’s School (DE). Nigel is a graduate of Boston Latin School and holds a B.A. in American History with a minor in African American Studies from The University of Pennsylvania, an M.A. in American History from Villanova University, and an M.Ed. in Organization and Private School Leadership from Columbia University. PRINCIPAL, FIELDSTON LOWER - Joseph McCauley previously served as Assistant Head of Pre- and Lower School at The Packer Collegiate Institute before joining Fieldston. He joined Packer in 2008 as a fourth-grade teacher. During his time there, he was Director of the Teacher Mentor Program, Leader of Yearlong Staff Development Groups, and a member of the Lower School Curriculum Leadership Team, as well as the Strategic Plan Task Force on Community and Identity. -

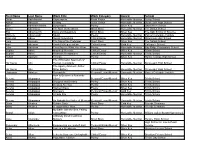

First Name Last Name Work Title Work Category Award School

First Name Last Name Work Title Work Category Award School Omar Abdelhamid Skyscrapers Flash Fiction Honorable Mention Trinity School Adrian Aboyoun Driving Flash Fiction Honorable Mention Stuyvesant High School Edie Abraham-Macht Suspended Poetry Silver Key Saint Ann's School Grace Abrahams The Man on the Street Short Story Honorable Mention The Dalton School Etai Abramovich Sons and Daughters Short Story Silver Key The Salk School of Science Michelle Abramowitz Squid Poetry Honorable Mention Packer Collegiate Institute Diamond Abreu Social Networking Critical Essay Honorable Mention Millennium High School Lucy Ackman The Day of the Professor Short Story Silver Key The Dalton School max adelman Hamlet's Regeneration Critical Essay Gold Key Collegiate School Lebe Adelman They Say It’s What You Wear Poetry Honorable Mention Bay Ridge Preparatory School Sophia Africk Morphed Mercutio Critical Essay Silver Key Trinity School Sophia Africk Richard's Realizations Critical Essay Honorable Mention Trinity School Rohan Agarwal Friends Poetry Silver Key Hunter College High School The Whitmanic Spectrum of Ha Young Ahn Human Immortality Critical Essay Honorable Mention Stuyvesant High School The Agency Moment: Arthur Ha Young Ahn Miller Edition Critical Essay Honorable Mention Stuyvesant High School Hadassah Akinleye Second Air Personal Essay/Memoir Honorable Mention Packer Collegiate Institute How to Become a Romantic Serena Alagappan Cliché Personal Essay/Memoir Silver Key Trinity School Serena Alagappan Drugged and Dreamy Poetry Silver Key Trinity -

My Name Is Leonie Haimson

This letter, written by Class Size Matters and Advocates for Children in Feb. 2004, protesting the Mayor’s proposal to hold back students on the basis of their test scores was signed by 107 eminent academics, researchers, and national experts on testing who say that such a policy is unfair and unreliable, and is likely to lead to lower achievement and higher drop out rates.1 The signers included four past presidents of the American Education Research Association, the nation’s premier organization of educational researchers, as well as the chair of the National Academy of Sciences Committee on the Appropriate Use of Educational Testing, and several members of the Board on Testing and Assessment of the National Research Council. Signers also included Dr. T. Berry Brazelton, renowned pediatrician and author of numerous works on child care and development, Robert Tobias, former head of Division of Assessment and Accountability for the Board of Education and now Director of the Center for Research on Teaching and Learning at NYU, and Dr. Ernest House, who did the independent evaluation of New York City’s failed “Gates” retention program in the 1980’s. Even the two companies that produce the third grade tests are on record that a decision to hold back a child should never be based upon test scores alone. February 11, 2004 Dear Mayor Bloomberg and Chancellor Klein: We ask that you reconsider and withdraw your proposal to retain 3rd grade students on the basis of test scores. All of the major educational research and testing organizations oppose using test results as the sole criterion for advancement or retention, since judging a particular student on the basis of a single exam is an inherently unreliable and an unfair measure of his or her actual level of achievement. -

Stuyvesant High School Faculty Email Addresses

STUYVESANT HIGH SCHOOL FACULTY EMAIL ADDRESSES FIRST LAST DEPARTMENT EMAIL ADDRESS Natalie Acevedo Secretary [email protected] Ulugbek Akhmedov Physics [email protected] Frida Ambia Language [email protected] Sushma Arora Chemistry [email protected] Marvin Autry Physical Education [email protected] John Avallone Physics [email protected] Deena Avigdor Mathematics [email protected] Perry Badgley Social Studies [email protected] Shangaza Banfield Biology [email protected] Howard Barbin Physical Education [email protected] Susan Barrow Art [email protected] Zachary Berman Social Studies [email protected] Leslie Bernstein Technology [email protected] Joseph Blay Technology [email protected] Harvey Blumm Internships Coord. [email protected] W illiam Boericke Social Studies [email protected] Peter Bologna Physical Education [email protected] Christopher Bowlin Librarian [email protected] Sandra Brandan Guidance [email protected] Lee Brando Social Studies [email protected] Carlos Bravo Language [email protected] Susan Brockman Language [email protected] Peter Brooks Computer Science [email protected] Christopher Brown Mykolyk Computer Science [email protected] Aurea Bullock Health Aide [email protected] Devon Butler Mathematics [email protected] Theresa Bynum Support [email protected] Stephen Cardella Lab Specilist [email protected] Carol Carrano Secretary [email protected] -

Pathways to an Elite Education: Exploring

POLICY BRIEF Pathways to an Elite Education: Exploring Strategies to Diversify NYC’s Specialized High Schools Sean P. Corcoran Institute for Education and Social Policy New York University Christine Baker-Smith The Research Alliance for New York City Schools New York University March 2015 1 PATHWAYS TO AN ELITE EDUCATION: EXPLORING STRATEGIES TO DIVERSIFY NYC’S SPECIALIZED HIGH SCHOOLS Introduction New York City’s specialized high schools have a long history of offering a rigorous, college preparatory, public education to some of NYC’s highest-achieving students. Unlike other high schools in the City, these eight schools admit students based solely on their performance on the Specialized High School Admissions Test (SHSAT). In a typical year, about 25,000 8th graders take the SHSAT (which is free), and 5,000 are offered admission to a specialized high school. These admitted students represent about 6 percent of the 80,000 or more 8th graders who participate in NYC’s high school admissions process each year. Despite enrolling only a small fraction of the City’s high school students, the specialized schools have become a This brief is based on a working paper, Pathways powerful symbol in a larger public debate about educational to an Elite Education: equity. For years, these elite schools have served Application, Admission, and Matriculation at New disproportionately low numbers of Black, Latino, and female York City’s Specialized students. In 2013, for example, at the three largest specialized High Schools. Please see th the paper (available at high schools, 57 percent of incoming 9 graders were male, www.ranycs.org/publicatio 64 percent were Asian, and 22 percent were White, while just ns/pathways_to_an_elite_ education) for information 4 percent were Black and 5 percent Latino.