Before It's Too Late

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iraqi Diaspora in Arizona: Identity and Homeland in Women’S Discourse

Iraqi Diaspora in Arizona: Identity and Homeland in Women’s Discourse Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Hattab, Rose Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 30/09/2021 20:53:34 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/634364 IRAQI DIASPORA IN ARIZONA: IDENTITY AND HOMELAND IN WOMEN’S DISCOURSE by Rose Hattab ____________________________ Copyright © Rose Hattab 2019 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty oF the SCHOOL OF MIDDLE EASTERN AND NORTH AFRICAN STUDIES In Partial FulFillment oF the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2019 2 3 DEDICATION This thesis is gratefully dedicated to my grandmothers, the two strongest women I know: Rishqa Khalaf al-Taqi and Zahra Shibeeb al-Rubaye. 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and Foremost, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Dr. Hudson for her expertise, assistance, patience and thought-provoking questions. Without her help, this thesis would not have been possible. I would also like to thank the members oF my thesis advisory committee, Dr. Julia Clancy-Smith and Dr. Anne Betteridge, For their guidance and motivation. They helped me turn this project From a series oF ideas and thoughts into a Finished product that I am dearly proud to call my own. My appreciation also extends to each and every Iraqi woman who opened up her heart, and home, to me. -

Gurriculum Vitae

حوكمةتا هةريَما كوردستانىَ – عرياق حكومت أقليم كودستان – العراق وزارة التعليم العالي والبحث العلمي وةزراتا خوندنا باﻻ وتوذينيَت زانستى رئاست جامعت بولينكنيك دهوك سةوركاتيا زانلويا ثوليتةكنيلا دهوك Kurdistan Regional Government-Iraq Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research Duhok Polytechnic University Curriculum Vitae University Address: 61 Zahko Road, 1006 Mazi Qt., Duhok , Kurdistan -Iraq A / Personal data Name: Mohammed Haydar Mosa Date of Birth: 1/1/1971 Place of Birth: Mosul City \ lraq Marital Status: Married Mother Tongue: Kurdish Other Language: Kurdish, English and Arabic Degree: M.Sc. Nursing from Nursing College/ Mosul University\ Iraq 2005 B\Educational University University Collage Degree Date (Year) Specialty Mosul Mosul Technical Technical Diploma 199 - 1993 Anesthesia Institute\Iraq Institute\Iraq Mosul College of Nursing B.SC 1994 - 1998 University Nursing Science Mosul College of Pediatric M.SC 2003 - 2005 University Nursing health nursing C\Training and education: Name ,Place , Country Type Years attended Academic degree obtained From To Tumor workshop \ Tumor 21/9/1996 - 29/9/1996 Training Mosul \Iraq nursing Second conference tumor Tumor 22/9/1996 - 24/9/1996 Training Of Mosul \Iraq Course & methods to teach public health\ Community 12 October 2004 Training Community health health nursing - 15 October 2004 nursing \ Duhok \ Iraq Cardiac catheterization Cardiac \ Azadi teaching 2007 Training catheterization hospital \Duhok\ Iraq Methods of education Methods of \Duhok Technical 4/7/2009 - 18/7/2006 education institute \Iraq Evaluation of health Environmental states At health Institutions In 7th scientific conference conference 27-28 September 2010 Iraq. Mosul proceedings university\Nursing collage The role of Scientific research in Developing 10th National scientific of public health . -

29 July 2019 the Challenges of Winning Justice for Victims Of

29 July 2019 The Challenges of Winning Justice for Victims of Sexual Abuse in War and Peacekeeping. On April 23rd 2019, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) adopted resolution 2467 on women, peace and security stating its concern over the slow progress in addressing and eliminating sexual violence in armed conflicts. Sexual violence in conflict as a topic has been gaining momentum over the last years, which led to two women’s rights advocates, Nadia Murad and Dr. Denis Mukwege, winning the Nobel Peace Prize in 2018. The UN has used this momentum to push governments to adopt national action plans to fight conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV). However, as of April 2019, only 79 out of 193 UN member states have produced such a national action plan. The UNSC is to be commended for continuing to place pressure on member states to deal with this important issue. However, this latest resolution raises two important issues that remain insufficiently addressed: victims’ access to justice and the separation of sexual abuse by UN staff from CRSV. While resolution 2467 contains strong language condemning CRSV, the issue of sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) by peacekeepers is not addressed. Nor it is acknowledged in the resolution as being a form of sexual violence in conflict even though since 2010, no less than 188 allegations of SEA by peacekeepers have been reported to the UN. At the core of both CRSV and SEA is sexual abuse by people in positions of power. One of the main differences between the two concepts lies in who is perpetrating the violence: state and non-state actors or UN peacekeepers. -

The Future of Mosul Before, During, and After the Liberation

1 The Future of Mosul Before, During, and After the Liberation Dylan O’Driscoll Research Fellow Middle East Research Institute September 2016 About MERI The Middle East Research Institute engages in policy issues contributing to the process of state building and democratisation in the Middle East. Through independent analysis and policy debates, our research aims to promote and develop good governance, human rights, rule of law and social and economic prosperity in the region. It was established in 2014 as an independent, not-for-profit organisation based in Erbil, Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Middle East Research Institute 1186 Dream City Erbil, Kurdistan Region of Iraq T: +964 (0)662649690 E: [email protected] www.meri-k.org NGO registration number. K843 © Middle East Research Institute, 2016 The opinions expressed in this publication are the responsibility of the author. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. Please direct all enquiries to the publisher. About the Author Dylan O’Driscoll is a Research Fellow in International Politics and National Security Programme at the Middle East Research Institute (MERI). He holds a PhD and MA from the University of Exeter, UK. Acknowledgments I would like to thank all the interviewees and people I had discussions with on the topic for giving me their time, local knowledge and personal insights. A very special thanks goes to Shivan Fazil for his help in organising the interviews and kick off workshop, his input towards the project and for his much-needed interpreting skills. -

COVID-19 Camp Vulnerability Index As of 04 May 2020

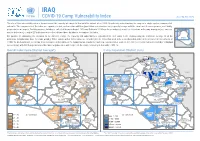

IRAQ COVID-19 Camp Vulnerability Index As of 04 May 2020 The aim of this vulnerability index is to understand the capacity of camps to deal with the impact of a COVID-19 outbreak, understanding the camp as a single system composed of sub-units. The components of the index are: exposure to risk, system vulnerabilities (population and infrastructure), capacity to cope with the event and its consequences, and finally, preparedness measures. For this purpose, databases collected between August 2019 and February 2020 have been analysed, as well as interviews with camp managers (see sources next to indicators), a total of 27 indicators were selected from those databases to compose the index. For purpose of comparing the situation on the different camps, the capacity and vulnerability is calculated for each camp in the country using the arithmetic average of all the IRAQ indicators (all indicators have the same weight). Those camps with a higher value are considered to be those that need to be strengthened in order to be prepared for an outbreak of COVID-19. Each indicator, according to its relevance and relation to the humanitarian standards, has been evaluated on a scale of 0 to 100 (see list of indicators and their individual assessment), with 100 being considered the most negative value with respect to the camp's capacity to deal with COVID-19. Overall Index Score (District Average*) Camp Population (District Sum) TURKEY TURKEY Zakho Zakho Al-Amadiya 46,362 Al-Amadiya 32 26 3,205 DUHOK Sumail DUHOK Sumail Al-Shikhan 83,965 Al-Shikhan Aqra -

Iraq: Opposition to the Government in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI)

Country Policy and Information Note Iraq: Opposition to the government in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) Version 2.0 June 2021 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the Introduction section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis and assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment of, in general, whether one or more of the following applies: • A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm • The general humanitarian situation is so severe as to breach Article 15(b) of European Council Directive 2004/83/EC (the Qualification Directive) / Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules • The security situation presents a real risk to a civilian’s life or person such that it would breach Article 15(c) of the Qualification Directive as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iv) of the Immigration Rules • A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) • A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory • A claim is likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and • If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. -

COI Note on the Situation of Yazidi Idps in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq

COI Note on the Situation of Yazidi IDPs in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq May 20191 Contents 1) Access to the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KR-I) ................................................................... 2 2) Humanitarian / Socio-Economic Situation in the KR-I ..................................................... 2 a) Shelter ........................................................................................................................................ 3 b) Employment .............................................................................................................................. 4 c) Education ................................................................................................................................... 6 d) Mental Health ............................................................................................................................ 8 e) Humanitarian Assistance ...................................................................................................... 10 3) Returns to Sinjar District........................................................................................................ 10 In August 2014, the Islamic State of Iraq and Al-Sham (ISIS) seized the districts of Sinjar, Tel Afar and the Ninewa Plains, leading to a mass exodus of Yazidis, Christians and other religious communities from these areas. Soon, reports began to surface regarding war crimes and serious human rights violations perpetrated by ISIS and associated armed groups. These included the systematic -

Report on the Protection of Civilians in the Armed Conflict in Iraq

HUMAN RIGHTS UNAMI Office of the United Nations United Nations Assistance Mission High Commissioner for for Iraq – Human Rights Office Human Rights Report on the Protection of Civilians in the Armed Conflict in Iraq: 11 December 2014 – 30 April 2015 “The United Nations has serious concerns about the thousands of civilians, including women and children, who remain captive by ISIL or remain in areas under the control of ISIL or where armed conflict is taking place. I am particularly concerned about the toll that acts of terrorism continue to take on ordinary Iraqi people. Iraq, and the international community must do more to ensure that the victims of these violations are given appropriate care and protection - and that any individual who has perpetrated crimes or violations is held accountable according to law.” − Mr. Ján Kubiš Special Representative of the United Nations Secretary-General in Iraq, 12 June 2015, Baghdad “Civilians continue to be the primary victims of the ongoing armed conflict in Iraq - and are being subjected to human rights violations and abuses on a daily basis, particularly at the hands of the so-called Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant. Ensuring accountability for these crimes and violations will be paramount if the Government is to ensure justice for the victims and is to restore trust between communities. It is also important to send a clear message that crimes such as these will not go unpunished’’ - Mr. Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, 12 June 2015, Geneva Contents Summary ...................................................................................................................................... i Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 Methodology .............................................................................................................................. -

Kurdistan Regional Government

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 04/13/2021 9:45:57 AM Newroz Video Message from KRG Representation in USA 1 message Kurdistan Regional Government - USA <[email protected]> Sun, Mar 21,2021 at 1:28 PM Reply-To: [email protected] To: [email protected] Kurdistan Regional Government Representation in the United States Washington D.C. Newroz Video Message from KRG Representation in USA Every year we look forward to celebrating Newroz, the Kurdish new year, and the arrival of spring on March 21st. Through gatherings with family, friends, and community, we also celebrate our people's liberation from tyranny and demonstrate support for the Kurdish cause. Regrettably, this year, we had to celebrate Newroz far away from each other due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Consequently, on March 5th, we invited you to submit a short video Newroz message of yourself or with your loved ones, answering the question: what does Newroz mean to you or remind you of? The answer is in this video. Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 04/13/2021 9:45:57 AM Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 04/13/2021 9:45:57 AM piroa ©e 9fa^/?y Aft jro/ Sign Up for KRG Updates Share the Podcast Follow us Share Tweet Share oo NOTIFICATION: The Kurdistan Regional Government Liaison Office - U.S.A. is registered as an agent of the Kurdistan Regional Government under 22 U.S.C. § 611 et seq. | 1532 16th Street, NW, Washington, DC 20036 Unsubscribe [email protected] Update Profile | Customer Contact Data Notice Sent by [email protected] powered by Constant Contact ©Try email marketing for free today! Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 04/13/2021 9:45:57 AM Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 04/13/2021 9:45:57 AM Reminder: KRG-US March 2021 newsletter 1 message Kurdistan Regional Government - USA <[email protected]> Sat, Apr 3, 2021 at 6:13 PM Reply-To: [email protected] To: [email protected] Kurdistan Regional Government Representation in the United States Washington D.C. -

The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq

The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq Julie Ahn—Maeve Campbell—Pete Knoetgen Client: Office of Iraq Affairs, U.S. Department of State Harvard Kennedy School Faculty Advisor: Meghan O’Sullivan Policy Analysis Exercise Seminar Leader: Matthew Bunn May 7, 2018 This Policy Analysis Exercise reflects the views of the authors and should not be viewed as representing the views of the US Government, nor those of Harvard University or any of its faculty. Acknowledgements We would like to express our gratitude to the many people who helped us throughout the development, research, and drafting of this report. Our field work in Iraq would not have been possible without the help of Sherzad Khidhir. His willingness to connect us with in-country stakeholders significantly contributed to the breadth of our interviews. Those interviews were made possible by our fantastic translators, Lezan, Ehsan, and Younis, who ensured that we could capture critical information and the nuance of discussions. We also greatly appreciated the willingness of U.S. State Department officials, the soldiers of Operation Inherent Resolve, and our many other interview participants to provide us with their time and insights. Thanks to their assistance, we were able to gain a better grasp of this immensely complex topic. Throughout our research, we benefitted from consultations with numerous Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) faculty, as well as with individuals from the larger Harvard community. We would especially like to thank Harvard Business School Professor Kristin Fabbe and Razzaq al-Saiedi from the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative who both provided critical support to our project. -

Dead Men Tell No Lies: Using Martyr Data to Expose the PKK's Regional

Dead Men Tell No Lies: Using Martyr Data to Expose the PKK’s Regional Shell Game Jared Ferris and Andrew Self May 05, 2015 1 Table of Contents • List of Figures in Appendix 3 • Acknowledgments 4 • Introduction 5 o Terms and Usage 7 o Literature Review 8 o Methodology/Data 12 o Background 14 • Beginning of the PJAK and PKK Franchise Era 16 • The PKK in Syria 21 o The PYD and Syrian Kurds 2003-2011 23 o The Syrian Civil War 27 • New Opportunities: ISIS, Kobani, and Sinjar 31 • Conclusion 37 • Appendix I- Figures 38 • Appendix II- PKK Military Organizational Structure Chart 46 • Appendix III- Sample “Marty” Announcements 47 • Appendix IV-Acronyms 48 • Bibliography 49 2 List of Figures in Appendix I • Figure 1: Total HPG Deaths by Country of Birth 38 • Figure 2: % of Total HPG Deaths by Country of Birth 38 • Figure 3: HPG Syrian Fighters City of Birth 39 • Figure 4: % of HPG Deaths Country of Birth: Iran vs Syria 39 • Figure 5: HPG Fighter Year of Join by % of Country of Birth 40 • Figure 6: Total Number of HPG Fighters by Year Joined 40 • Figure 7: Total HPG Deaths by Country of Birth 2001-2015 41 • Figure 8: % of HPG Combat Deaths by Country of Death 2001-2015 41 • Figure 9: % of HPG Combat Deaths by Country of Death 42 • Figure 10: YPG Combat Deaths by Country of Birth: Oct 2013-June 2014 43 • Figure 11: YPG Combat Deaths by Country of Birth: July 2014-Feb 2015 43 • Figure 12: YPG Combat Deaths by Country of Birth: Nov 2013-Feb 2015 44 • Figure 13: Map of HPG Combat Deaths in Iran 45 3 Acknowledgements We would like to thank our advisor Dr. -

Kirkuk and Its Arabization: Historical Background and Ongoing Issues In

Abstract The Arabization of the Kurdistan region in Iraq Since the establishment of the Iraqi state, the ruling Arab regimes forcibly displaced native Kurds and repopulated the area with Arab tribes. The change of demography,known as “Arabization,” existed in both Kurdish majority agriculture and urban lands. These policies were part of a larger Iraqi campaign to erase the Kurdish identity, occupy Kurdistan, and control its wealth. The Iraqi government’s campaign against the Kurds amounted to genocide and eventually destroyed Kurdish communities and the social fabric of Kurdistan. The areas affected by the Arabization stretch from eastern to northwestern Iraq , incorporating major cities,towns, and hundreds of villages. After the fall of Saddam Hussien’s dictatorship, these areas became referred to as “Disputed Territories'' in Iraq’s newly adopted constitution of 2005. Article 140 of Iraq’s constitution called for the normalization of the “Disputed Territories,” which was never implemented by the federal government of Iraq. 1 www.dckurd.org Kirkuk province, Khanagin city of Diyala province, Tuz Khurmatu District of Saladin Province, and Shingal (Sinjar) in Nineveh province are the main areas that continue to suffer from Arabization policies implemented in 1975. KIRKUK A key feature of Kirkuk is its diversity – Kurds, Arabs, Turkmens, Shiites, Sunnis, and Christians (Chaldeans and Assyrians) all co-exist in Kirkuk, and the province is even home to a small Armenian Christian population. GEOGRAPHY The province of Kirkuk has a population of more than 1.4 million, the overwhelming majority of whom live in Kirkuk city. Kirkuk city is 160 miles north of Baghdad and just 60 miles from Erbil, the capital of the Iraqi Kurdistan region.