1 Afrisam (South Africa) Properties (Pty) Ltd: Ulco Cement Plant And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE HISTORY of TSE KIMBERLEY PUBLIC LIBRARY Febe Van

THE HISTORY OF TSE KIMBERLEY PUBLIC LIBRARY 1870 - 1902 Febe van Niekerk Submitted to fulfil the requirement of the degree MAGISTER BIBLIOTBECOLOGIAE in the FACULTY OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF INFORMATION SCIENCE at the • UNIVERSITY OF THE ORANGE FREE STATE Supervisor : Prof D w Fokker September 1990 Co-supervisor: Prof A H Marais FOR MY FAMILY, BEN, PHILIP, NOELINE AND RENETTE AND GRANDSONS, IVAN AND BRYCE. i TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 The problem and its setting 1 1.2 The purpose of the study 2 1.3 The sub-problems 3 1.4 The hypotheses 3 1.5 Assumptions 4 1.6 The delimitations 5 1.7 Definition of terms 5 1.8 Abbreviations 7 1.9 The need for the study 8 1.10 Methodology of study 9 2. ECONOMIC, POLITICAL AND HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 12 2.1 The beginning 12 2.2 The birth of a city 17 2.3 Social and cultural background 18 2.4 Conclusion 22 3. EARLY LIBRARY HISTORY 2·3 3.1 Library development in England 23 3.1.1 The Free Libraries' Act 24 3.1.2 Mechanics' Institutions 25 3.1.3 Book Clubs and Circulating Libraries 26 3.2 Libraries in America 26 3.3 Library conditions at the Cape 27 3.3.1 The South African Library 27 3.3.2. Other South African libraries 29 3.4 Conclusion 30 4. THE FIRST ATTEMPT AT ESTABLISHING A PUBLIC LIBRARY IN KIMBERLEY 3 2 4.1 Early Reading Rooms and Circulating Libraries 32 4.2 The establishment of the first Public Library 39 4.3 Conclusion 54 5. -

Ganspan Draft Archaeological Impact Assessment Report

CES: PROPOSED GANSPAN-PAN WETLAND RESERVE DEVELOPMENT ON ERF 357 OF VAALHARTS SETTLEMENT B IN THE PHOKWANE LOCAL MUNICIPALITY, FRANCES BAARD DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY, NORTHERN CAPE PROVINCE Archaeological Impact Assessment Prepared for: CES Prepared by: Exigo Sustainability ARCHAEOLOGICAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (AIA) ON ERF 357 OF VAALHARTS SETTLEMENT B FOR THE PROPOSED GANSPAN-PAN WETLAND RESERVE DEVELOPMENT, FRANCES BAARD DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY, NORTHERN CAPE PROVINCE Conducted for: CES Compiled by: Nelius Kruger (BA, BA Hons. Archaeology Pret.) Reviewed by: Roberto Almanza (CES) DOCUMENT DISTRIBUTION LIST Name Institution Roberto Almanza CES DOCUMENT HISTORY Date Version Status 12 August 2019 1.0 Draft 26 August 2019 2.0 Final 3 CES: Ganspan-pan Wetland Reserve Development Archaeological Impact Assessment Report DECLARATION I, Nelius Le Roux Kruger, declare that – • I act as the independent specialist; • I am conducting any work and activity relating to the proposed Ganspan-Pan Wetland Reserve Development in an objective manner, even if this results in views and findings that are not favourable to the client; • I declare that there are no circumstances that may compromise my objectivity in performing such work; • I have the required expertise in conducting the specialist report and I will comply with legislation, including the relevant Heritage Legislation (National Heritage Resources Act no. 25 of 1999, Human Tissue Act 65 of 1983 as amended, Removal of Graves and Dead Bodies Ordinance no. 7 of 1925, Excavations Ordinance no. 12 of 1980), the -

Wood 2 & 3 Solar Energy Facilities

Bind aan Rugkant van A4 Dokument Lourens G van Zyl (Mobile) +27 (0)76 371 1151 WELCOME WOOD 2 & 3 SOLAR ENERGY FACILITIES (Website) www.terragis.co.za (Email) [email protected] Locality Map 21°30'0"E 22°0'0"E 22°30'0"E 23°0'0"E 23°30'0"E 24°0'0"E 24°30'0"E 25°0'0"E ! R S " - 0 e K P 1 ! 2 1 l h Tlakgameng 3 go 0 o k e 0 0 g gole kgole p 7 ' 0 k o go T 7 Atamelang g a 0 0 K 0 K n l ! 0 e a 3 0 p ! 0 Geysdorp 0 Stella ° 0 e e 0 ! R 0 n n 6 g 0 0 5 g a 2 0 n Ganyesa 0 e ! s 7 a w o h a s p o s a M e R3 h Molop o y 77 Mo n P s a h aweng ! G R 3 78 t ui L pr olwa us nen ee Van g L 0 8 Zylsrust 3 ! M Moseohatshe R ! t a i t u l Ditshipeng r h p o ! s S Vryburg t t " R31 s ! D ie S H " 0 h R r ' a L sase o o 0 n a e ' 0 s e e r a 0 ° t s n s o ° 7 a M tlh arin g Bothithong L n w g e 7 2 Kuruma K ! Tsineng o 6 2 r u ! K s 0 r or D t R a u o 5 m n bel r 34 a M a -3000000 r a -30000R00 a o M H g s K o o a h robela Wentzel a M tl Ko - hw Lo it ro Schweizer g w b Dam a Ga Mopedi a u e ! ri ob r la ! ng ate e p G s 9 n e reneke lw 4 Amalia g o kane ! s R t M W ro 4 Har Wit M a 50 lee a R g n Ma t y t e e lh d w g in a n Mothibistad g rin udum o 0 ! g Pudimoe P G 8 g ! 3 ! n e a Kuruman i G M t - R d S ! l M a " Bodulong o e - a S V M e o K " h y m 0 l n e a ' s g u a r n a ng y 0 n s e n ' a m n 0 r a o a um e k o 0 r u 6 3 a s p T im a is n M 0 3 ° e l o h e a Manthestad 5 ° 7 o p e Reivilo R372 ! ! R g 7 2 D e R ! h DibG eng R t 37 B e 2 lu 2 s ! 3 4 e Taung t a 8 1 P a - o 0 N ol M m 1 M o 7 - g 3 ! a a Kathu R r ! G a e Phok a n Dingleton -

Northern Cape Planning and Development Act No 7 of 1998

EnviroLeg cc NORTHERN CAPE Prov p 1 NORTHERN CAPE PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT ACT NO 7 OF 1998 Assented to: 4 April 2000 Date of commencement: 1 June 2000 INTRODUCTION Definitions 1. In this Act, unless the context otherwise indicates. chief executive officer means the chief executive officer of a competent authority or the chief executive officer of another competent authority who acts on behalf of the administration of the first mentioned competent authority as an agent or according to special arrangements; competent authority means a transitional local council, a transitional rural or representative council, a district council or any other body or authority designated by the MEC by notice in the Provincial Gazette to exercise the powers as are mentioned in the notice; consent use means a use, together with any land use restrictions, permitted within a particular zone with the consent of a competent authority in terms of an approved zoning scheme and land development procedures and regulations; conveyancer means a conveyancer as defined in section 102 of the Deeds Registry Act, 1937 (Act No 47 of 1937); deeds registry means a deeds registry as defined in section 102 of the Deeds Registry Act, 1937 (Act No 47 of 1937); department head means the head of the department within the Provincial Government of the Northern Cape charged with the responsibility for the administration of this Act; departure means an altered land use granted in terms of the provisions of this Act or in terms of an approved zoning scheme and land development procedures -

Explore the Northern Cape Province

Cultural Guiding - Explore The Northern Cape Province When Schalk van Niekerk traded all his possessions for an 83.5 carat stone owned by the Griqua Shepard, Zwartboy, Sir Richard Southey, Colonial Secretary of the Cape, declared with some justification: “This is the rock on which the future of South Africa will be built.” For us, The Star of South Africa, as the gem became known, shines not in the East, but in the Northern Cape. (Tourism Blueprint, 2006) 2 – WildlifeCampus Cultural Guiding Course – Northern Cape Module # 1 - Province Overview Component # 1 - Northern Cape Province Overview Module # 2 - Cultural Overview Component # 1 - Northern Cape Cultural Overview Module # 3 - Historical Overview Component # 1 - Northern Cape Historical Overview Module # 4 - Wildlife and Nature Conservation Overview Component # 1 - Northern Cape Wildlife and Nature Conservation Overview Module # 5 - Namaqualand Component # 1 - Namaqualand Component # 2 - The Hantam Karoo Component # 3 - Towns along the N14 Component # 4 - Richtersveld Component # 5 - The West Coast Module # 5 - Karoo Region Component # 1 - Introduction to the Karoo and N12 towns Component # 2 - Towns along the N1, N9 and N10 Component # 3 - Other Karoo towns Module # 6 - Diamond Region Component # 1 - Kimberley Component # 2 - Battlefields and towns along the N12 Module # 7 - The Green Kalahari Component # 1 – The Green Kalahari Module # 8 - The Kalahari Component # 1 - Kuruman and towns along the N14 South and R31 Northern Cape Province Overview This course material is the copyrighted intellectual property of WildlifeCampus. It may not be copied, distributed or reproduced in any format whatsoever without the express written permission of WildlifeCampus. 3 – WildlifeCampus Cultural Guiding Course – Northern Cape Module 1 - Component 1 Northern Cape Province Overview Introduction Diamonds certainly put the Northern Cape on the map, but it has far more to offer than these shiny stones. -

Report Format NI 43-101 (Rockwell)

2010 Tania R Marshall Explorations Unlimited Glenn A Norton Rockwell Diamonds Inc REVISED TECHNICAL REPORT ON THE KLIPDAM/HOLPAN ALLUVIAL DIAMOND MINE (INCORPORATING THE KLIPDAM, HOLPAN MINES AND THE ERF 1 AND ERF 2004 PROSPECTING PROPERTIES), BARKLY WEST DISTRICT, NORTHERN CAPE PROVINCE, REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA FOR ROCKWELL DIAMONDS INC Effective Date: 30 November 2010 Signature Date: 30 May 2011 Revision Date: 30 June 2011 ROCKWELL DIAMONDS INC, KLIPDAM/HOLPAN MINE November 30, 2010 Table of Contents Page 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................... 14 1.1 TERMS OF REFERENCE AND SCOPE OF WORK ....................................................................................................... 14 1.2 SOURCES OF INFORMATION .............................................................................................................................. 17 1.3 UNITS AND CURRENCY .................................................................................................................................... 17 1.4 FIELD INVOLVEMENT OF QUALIFIED PERSONS ...................................................................................................... 17 1.5 USE OF DATA ................................................................................................................................................ 18 2 RELIANCE ON OTHER EXPERTS .................................................................................................................... -

A History of the Kimberley Africana Library

Fig. 1: JL Lieb: A map of the Griqua territory and part of the Bechuana country of South Africa, 1830 (M029) THE HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE KIMBERLEY AFRICANA LIBRARYAND ITS RELATIONSHIP WITH THE KIMBERLEY PUBLIC LIBRARY by ROSEMARY JEAN HOLLOWAY submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF INFORMATION SCIENCE at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR : PROFESSOR T B VAN DER WALT SEPTEMBER 2009 i TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD SUMMARY ABBREVIATIONS CHAPTER 1 The history and development of the Kimberley Africana Library and its relationship with the Kimberley Public Library 1.1 Introduction ……….. ……….. ………. 1 1.2 Background to the study ……….. ……….. ………. 2 1.3 The aim, purpose and value of the study ……….. ………. 7 1.4 Delimitation ……….. ……….. ………. 9 1.5 Explanation of relevant concepts ……. ……….. ………. 11 1.6 Methodology and outline of the study ……….. ………. 12 CHAPTER 2 The Kimberley Public Library/Africana Library within an environmental perspective 2.1 Introduction ……….. ………… ………. 18 2.2 The land and the people ……….. ………… ………. 18 2.3 Politics and the economy ……….. ………… ………. 29 2.3.1 Kimberley and the growth of the South African economy ……….. ………… ……….. 30 2.3.2 Kimberley and local politics … ………… ……….. 32 2.3.3 British hegemony in South Africa and territorial claims ……….. ………… ……….. 33 2.3.4 From mining camp to a town .. ………… ……….. 35 2.3.5 The illicit trade in diamonds … ………… ……….. 36 2.3.6 International economic and political events to affect Kimberley ………… ………… ……….. 37 2.3.7 Conclusion ………... ………… ……….. 43 ii CHAPTER 3 The Kimberley Public Library within the context of the development of public libraries in South Africa 3.1 Introduction ………… ………… ………. -

Province Physical Suburb Physical Town Physical

PROVINCE PHYSICAL SUBURB PHYSICAL TOWN PHYSICAL ADDRESS1 PRACTICE NAME CONTACT NUMBER PRACTICE NUMBER NORTHERN CAPE MOTHIBISTAT BANKHARA BODULONG Kagiso Health Centre IFEBUZOR 0537121225 0516317 NORTHERN CAPE BARKLY WEST BARKLY WEST 4 Waterboer Street SLAZUS 0535310694 1483846 NORTHERN CAPE CALVINIA CALVINIA 34 Van Riebeeck Street COETZEE J E 0273411434 0193577 NORTHERN CAPE CARNARVON CARNARVON Cnr Hanau & New Street VORSTER A J INCORPORATED 0533823033 1563955 NORTHERN CAPE COLESBERG COLESBERG Cnr Kerk & New Street DE JONGH W A & PARTNERS 0517530701 1440330 NORTHERN CAPE DE AAR DE AAR 51 Church Street VAN ASWEGEN 0536312978 1456016 NORTHERN CAPE DE AAR DE AAR 51 Church Street VAN ASWEGEN AND PARTNERS 0536312978 0278629 NORTHERN CAPE DELPORTSHOOP DELPORTSHOOP 13 Hanekom Street DR D W MILLER PRIVATE PRACTICE INC AND PARTNERS 0535610506 0695149 NORTHERN CAPE ULCO DELPORTSHOOP Old Hospital Building MILLER 0535620010 0392731 NORTHERN CAPE ULCO DELPORTSHOOP 1 Werk Street VAN RENSBURG 0535629100 1556010 NORTHERN CAPE DOUGLAS DOUGLAS 15 Barkley Street MOROLONG 0532983989 1569996 NORTHERN CAPE DOUGLAS DOUGLAS 24 Campbell Street RICHARDS 0532982889 1516949 NORTHERN CAPE HARTSWATER HARTSWATER 45 D F Malan Street KUHN 0534740713 1482262 NORTHERN CAPE HARTSWATER HARTSWATER 11 Hertzog Street LOUW 0534742099 0476293 NORTHERN CAPE HARTSWATER HARTSWATER 28 Hertzog Street STEENKAMP & CONRADIE INCORPORATED 0534740157 1578103 NORTHERN CAPE HOPETOWN HOPETOWN 9 Van Riebeeck Street VERMEULEN 0532030119 1477595 NORTHERN CAPE HOTAZEL HOTAZEL 1 Duiker Street BOHNEN -

Organisational Development, Head Office

O R G A N I S A T I O N A L D E V E L O P M E N T , H E A D O F F I C E Coordinate System: Sphere Cylindrical Equal Area Projection: Cylindrical Equal Area Datum: Sphere North West Clusters False Easting: 0.0000 False Northing: 0.0000 Central Meridian: 0.0000 Standard Parallel 1: 0.0000 Units: Meter µ VAALWATER LEPHALALE LEPHALALE RANKIN'S PASS MODIIMOLLE DWAALBOOM THABAZIMBI MODIMOLLE BELA--BELA ROOIBERG BELA-BELA NORTHAM NIETVERDIEND MOTSWEDI BEDWANG CYFERSKUIL MOGWASE MADIKWE SUN CITY ASSEN KWAMHLANGA RUSTENBURG JERICHO MAKAPANSTAD ZEERUST PIENAARSRIVIER RIETGATTEMBA BRITS DUBE LETHABONG BRITS LOATEHAMMANSKRAAL LEHURUTSHE LETHLABILE GROOT MARICO KLIPGAT MOKOPONG ZEERUST PHOKENG TSHWANE NORTH MOTHUTLUNGHEBRONSOSHANGUVE CULLINAN BETHANIE SWARTRUGGENS BRITS GA-RANKUWAPRETORIA NORTH BOITEKONG BRAY TLHABANE MMAKAU TSHWANE EAST MARIKANA AKASIA SINOVILLE OTTOSHOOP HERCULES MOOINOOI ATTERIDGEVILLE SILVERTON MAHIKENG RUSTENBURG HARTBEESPOORTDAM MAKGOBISTAD TSHWANE WEST MMABATHO LYTTELTON TSHIDILAMOLOMO KOSTER ERASMIA HEKPOORT VORSTERSHOOP BOSHOEK DIEPSLOOTMIDRAND WELBEKEND LICHTENBURG MULDERSDRIFT LOMANYANENG BOONSMAGALIESBURGKRUGERSDORPJOBURG NORTH TARLTON ITSOSENG JOBURG WEST KEMPTON PARK SETLAGOLE HONEYDEWSANDTON KAGISO BENONI MOROKWENG RANDFONTEIN PIET PLESSIS MAHIKENG EKHURULENII CENTRAL MAHIKENG WEST RAND ALBERTON WEST RAND BRAKPAN VRYBURG MOOIFONTEIN KLERKSKRAAL CARLETONVILLE MONDEOR VENTERSDORP KHUTSONG SOWETO WEST DAWN PARK HEUNINGVLEI BIESIESVLEI COLIGNY MADIBOGO ATAMELANG WESTONARIA EKHURULENII WEST WEDELA ENNERDALEDE DEUR ORANGE -

14 Northern Cape Province

Section B:Section Profile B:Northern District HealthCape Province Profiles 14 Northern Cape Province John Taolo Gaetsewe District Municipality (DC45) Overview of the district The John Taolo Gaetsewe District Municipalitya (previously Kgalagadi) is a Category C municipality located in the north of the Northern Cape Province, bordering Botswana in the west. It comprises the three local municipalities of Gamagara, Ga- Segonyana and Joe Morolong, and 186 towns and settlements, of which the majority (80%) are villages. The boundaries of this district were demarcated in 2006 to include the once north-western part of Joe Morolong and Olifantshoek, along with its surrounds, into the Gamagara Local Municipality. It has an established rail network from Sishen South and between Black Rock and Dibeng. It is characterised by a mixture of land uses, of which agriculture and mining are dominant. The district holds potential as a viable tourist destination and has numerous growth opportunities in the industrial sector. Area: 27 322km² Population (2016)b: 238 306 Population density (2016): 8.7 persons per km2 Estimated medical scheme coverage: 14.5% Cities/Towns: Bankhara-Bodulong, Deben, Hotazel, Kathu, Kuruman, Mothibistad, Olifantshoek, Santoy, Van Zylsrus. Main Economic Sectors: Agriculture, mining, retail. Population distribution, local municipality boundaries and health facility locations Source: Mid-Year Population Estimates 2016, Stats SA. a The Local Government Handbook South Africa 2017. A complete guide to municipalities in South Africa. Seventh -

Sustainability Report Creating Concrete

SUSTAINABILITY REPORT CREATING CONCRETE POSSIBILITIES MESSAGE FROM THE CEO 3 ORGANISATIONAL PROFILE 4 SUSTAINABILITY REPORTING 7 GOVERNANCE 9 ECONOMIC SUSTAINABILITY 13 ABOUT THIS REPORT ENVIRONMENTAL SUSTAINABILITY 15 This is a summary of the sustainability activities relating to AfriSam (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd from 1 January 2015 to 31 December 2015. The reporting period is aligned to the company’s financial ETHICS AND INTEGRITY 17 reporting period and AfriSam aims to report annually on its sustainability performance. The report includes SOCIAL SUSTAINABILITY 19 information relating to AfriSam South Africa (Pty) Ltd operations in South Africa, Swaziland and Lesotho. PROTECTION OF HUMAN RIGHTS 22 AfriSam’s subsidiary in Tanzania, Tanga Cement Company Plc, is a publicly listed company on the Tanzania stock exchange and produces its own annual integrated report. This report is available from its website: www.simbacement.co.tz INDEX TO GLOBAL REPORTING This report has been produced giving due consideration to the Global Reporting Index (GRI) Core INITIATIVE INDICATORS 25 ‘In Accordance’ guidelines, as well as the United Nations Global Compact Active Level reporting requirements. We welcome your feedback on our sustainability reporting process. Please send comments or suggestions to: Report contact: Maxine Nel Physical address of headquarters: AfriSam (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd AfriSam House Reg. 2006/005970/07 Constantia Office Park Tel: +27 11 670 5893 Weltevredenpark Email: [email protected] 1715 2 MESSAGE FROM THE CEO Dear Stakeholders, The concept of sustainable development has long since formed the foundation for AfriSam’s business activities. It echoes an internal philosophy that we live on a daily basis. -

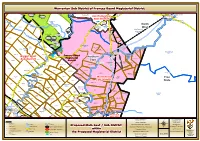

NC Sub Oct2016 FB-Warrenton.Pdf

# # !C # # ### ^ !C# !.!C# # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # ^!C # # # # # # # ^ # # ^ # # !C # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # !C!C # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # #!C# # # # !C# ^ # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # #!C # # # # # !C # #^ # # # # # # ## # #!C # # # # # # ## !C # # # # # # # !C# ## # # # # # !C # # !C# # #^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # !C # # # ## # # !C # # # # # # # # !C # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# !C # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # #^ !C #!C# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # #!C ## # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # !C # !C # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # !C# # # # # # !C## # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # ## ## # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # ## # # !C # # # # # # # ^ # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # !C # !C # #!C # # # # # #!C # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ### # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # #### # # # !C # # !C# # # # !C # ## !C # # # # # !C # !. # # # # # # # # # # ## # #!C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # ## ## # # # # # # # # # ^ # !C ## # # # # # # # # # !C# # # # # # # # # # ## # # ## # !C ## !C## # # # ## # !C # ## # !C# ## # # !C ## # !C # # ^ # ## # # # !C# ^ # # !C # # # !C ## # #!C ## # # # # # # # # ## # # # ## !C# ## # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # ^ # # !C # ## # ## # # # # !. # # # # # !C