Gagosian Gallery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

London Explorer Pass List of Attractions

London Explorer Pass List of Attractions Tower of London Uber Boat by Thames Clippers 1-day River Roamer Tower Bridge St Paul’s Cathedral 1-Day hop-on, hop-off bus tour The View from the Shard London Zoo Kew Gardens Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre Tour Westminster Abbey Kensington Palace Windsor Palace Royal Observatory Greenwich Cutty Sark Old Royal Naval College The Queen’s Gallery Chelsea FC Stadium Tour Hampton Court Palace Household Cavalry Museum London Transport Museum Jewel Tower Wellington Arch Jason’s Original Canal Boat Trip ArcelorMittal Orbit Beefeater Gin Distillery Tour Namco Funscape London Bicycle Hire Charles Dickens Museum Brit Movie Tours Royal Museums Greenwich Apsley House Benjamin Franklin House Queen’s Skate Dine Bowl Curzon Bloomsbury Curzon Mayfair Cinema Curzon Cinema Soho Museum of London Southwark Cathedral Handel and Hendrix London Freud Museum London The Postal Museum Chelsea Physic Garden Museum of Brands, Packaging and Advertising Pollock’s Toy Museum Twickenham Stadium Tour and World Rugby Museum Twickenham Stadium World Rugby Museum Cartoon Museum The Foundling Museum Royal Air Force Museum London London Canal Museum London Stadium Tour Guildhall Art Gallery Keats House Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art Museum of London Docklands National Army Museum London Top Sights Tour (30+) Palaces and Parliament – Top Sights Tour The Garden Museum London Museum of Water and Steam Emirates Stadium Tour- Arsenal FC Florence Nightingale Museum Fan Museum The Kia Oval Tour Science Museum IMAX London Bicycle Tour London Bridge Experience Royal Albert Hall Tour The Monument to the Great Fire of London Golden Hinde Wembley Stadium Tour The Guards Museum BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir Wernher Collection at Ranger’s House Eltham Palace British Museum VOX Audio Guide . -

Tees Valley Giants

5TEES VALLEY GIANTS TEES VALLEY GIANTS A series of five world-class art installations matched only in scale by the ambition of Tees Valley Regeneration in its instigation of the project. Temenos is the first iteration of the five sculptures that will combine as the world’s largest series of public art - the Tees Valley Giants. The epically scaled installations created by Turner Prize winning sculptor Anish Kapoor and pioneering structural designer Cecil Balmond, will soon grace the Tees Valley, with the first of these, Temenos, located at Middlehaven, Middlesbrough. Over the next decade four more structures will be located within each of the other four Tees Valley boroughs: Stockton, Hartlepool, Darlington and Redcar and Cleveland. Although each work is individually designed and specific to its location, the structures will be thematically related, visually linking the Tees Valley and highlighting the ambition for social, cultural and economic regeneration of the Tees Valley as a whole. Massive in impact, scale and world status, Tees Valley Giants is symbolic of the aspiration and ongoing commitment of Tees Valley Regeneration to enhance the way in which the Tees Valley is viewed and experienced. TEMENOS Temenos Greek, meaning ‘land cut off and assigned as sanctuary or holy area.’ Temenos is a bold contemporary artwork which also recalls the heritage of Middlesbrough and the Tees Valley. Its construction will call on the traditional twin skills of the region: precision engineering and heavy industry. Standing at a height of nearly 50 metres and spanning almost 120 metres in length, Temenos will stand shoulder-to-shoulder with Middlesbrough’s landmark Transporter Bridge. -

MKULTR4: Very Vague and Not Well-Funded Written and Edited by Emma Laslett, Ewan Macaulay, Joey Goldman, Ben Salter, and Oli Clarke Editors 5

MKULTR4: Very Vague And Not Well-Funded Written and Edited by Emma Laslett, Ewan MacAulay, Joey Goldman, Ben Salter, and Oli Clarke Editors 5 Tossups 1. An 1841 alternative history of the Gunpowder Plot by Harrison Ainsworth imagines Guy Fawkes meeting this man and the founder of Chetham’s Library. The British Museum holds an obsidian mirror that Horace Walpole believed belonged to this man. Michael Voynich assumed that the Voynich Manuscript had been sold by this man to Rudolf II, HRE. This man is usually credited with coining the idea of the “British Empire.” Robert Hooke suggested that this man was a (*) spy due to his use of cryptography to conceal correspondence with his patron. This man’s notebooks are in the Enochian language he developed with Edward Kelley. For 10 points name this occultist and advisor to Elizabeth I. ANSWER: John Dee <JG> 2. This artist worked on an installation that takes the form of two circles connected by a large net across a river. That work designed by this artist is Tenemos and it is the first of the five planned Tees Valley Giants. This artist frequently collaborates with Cecil Balmond. A museum-goer was recently hospitalised after falling into this artist’s Descent into Limbo. This artist holds an exclusive licence for use of the extremely (*) non-reflective substance Vantablack. This artist’s massive trumpet-like Marsyas filled the Tate’s Turbine Hall in 2003. This artist of Chicago’s Cloud Gate designed a 115 meter high curvy red nonsense for the Olympic Park. For 10 points, name this artist of the ArcelorMittal Orbit. -

Thomas Heatherwick, Architecture's Showman

Thomas Heatherwick, Architecture’s Showman His giant new structure aims to be an Eiffel Tower for New York. Is it genius or folly? February 26, 2018 | By IAN PARKER Stephen Ross, the seventy-seven-year-old billionaire property developer and the owner of the Miami Dolphins, has a winningly informal, old-school conversational style. On a recent morning in Manhattan, he spoke of the moment, several years ago, when he decided that the plaza of one of his projects, Hudson Yards—a Doha-like cluster of towers on Manhattan’s West Side—needed a magnificent object at its center. He recalled telling him- self, “It has to be big. It has to be monumental.” He went on, “Then I said, ‘O.K. Who are the great sculptors?’ ” (Ross pronounced the word “sculptures.”) Before long, he met with Thomas Heatherwick, the acclaimed British designer of ingenious, if sometimes unworkable, things. Ross told me that there was a presentation, and that he was very impressed by Heatherwick’s “what do you call it—Television? Internet?” An adviser softly said, “PowerPoint?” Ross was in a meeting room at the Time Warner Center, which his company, Related, built and partly owns, and where he lives and works. We had a view of Columbus Circle and Central Park. The room was filled with models of Hudson Yards, which is a mile and a half southwest, between Thirtieth and Thirty-third Streets, and between Tenth Avenue and the West Side Highway. There, Related and its partner, Oxford Properties Group, are partway through erecting the complex, which includes residential space, office space, and a mall—with such stores as Neiman Marcus, Cartier, and Urban Decay, and a Thomas Keller restaurant designed to evoke “Mad Men”—most of it on a platform built over active rail lines. -

Arcelormittal ORBIT

ArcelorMittal ORBIT Like many parents we try pathetically With the help of a panel of experts, to improve our kids by taking them to including Nick Serota and Julia Peyton- see the big exhibitions. We have trooped Jones, we eventually settled on Anish. through the Aztecs and Hockney and He has taken the idea of a tower, and Rembrandt – and yet of all the shows transformed it into a piece of modern we have seen there is only one that really British art. seemed to fire them up. It would have boggled the minds of the I remember listening in astonishment as Romans. It would have boggled Gustave they sat there at lunch, like a bunch of Eiffel. I believe it will be worthy of art critics, debating the intentions of the London’s Olympic and Paralympic Games, artist and the meaning of the works, and worthy of the greatest city on earth. but agreeing on one point: that these In helping us to get to this stage, were objects of sensational beauty. I especially want to thank David McAlpine That is the impact of Anish Kapoor on and Philip Dilley of Arup, and everyone Our ambition is to turn the young minds, and not just on young at the GLA, ODA and LOCOG. I am Stratford site into a place of minds. His show at the Royal Academy grateful to Tessa and also to Sir Robin destination, a must-see item on broke all records, with hundreds of Wales and Jules Pipe for their the tourist itinerary – and we thousands of people paying £12 to see encouragement and support. -

The Art of the Possible the Arcelormittal Orbit, Collective Memory, and Ecological Survival

The Art of the Possible The ArcelorMittal Orbit, collective memory, and ecological survival David Cross [For ‘Regeneration Songs: Sounds of Opportunity and Loss in East London’ Edited by Alberto Duman, Anna Minton, Dan Hancox and Malcolm James London: Repeater Books, September 2018] As the 2012 London Olympics have long since passed from anticipation through lived experience into history, or at least memory, I decided at last to ‘experience’ the ArcelorMittal Orbit in its physical setting. Emerging from Stratford tube station, I tried to reach the Olympic Park without passing through Westfield, Europe’s largest shopping centre. But the pedestrian walkway petered out in a banal and featureless non-place; with no viable way forward, I had to concede, and return to the main concourse. Surrounded by surveillance cameras, I felt self-conscious and began to suspect myself of having criminal thoughts. But with my field of vision dominated by a brilliant screen playing fragments of a disaster movie, interspersed with an advertisement for dairy milk chocolate, it was easy to be distracted. Framed by an avenue of retail façades, my first glimpse of the ArcelorMittal Orbit had the quality of a computer-generated image, a silhouette shimmering faintly in the polluted London air. Having found my bearings, I decided to relax and ‘go with the flow’, allowing my movement to be governed by the urban form. I wandered through the corporate branded environment, a ‘forest of signs’ enjoining me to “Explore, Discover, Experience, Share, Indulge, and Eat”. I went into a stylish boutique café with a ceiling of beaten copper and a display counter of authentic-looking wooden fruit packing crates, where I was served an organic fairtrade coffee and a delicious pain au chocolat, heated and handed to me in a recycled paper bag by someone who seemed so bored or exhausted that they were almost gone. -

My Show Friends!

15 My Show friends! Please see the floor plan on the previous page for stand locations and an alphabetical exhibitor list, and ask one of our Santa’s Little Helpers if you need help with finding the right exhibitors for your Christmas parties. ONE MOORGATE PLACE One Moorgate Place is a beautiful grade ll listed building in the heart of the city. Our range of elegant spaces can cater for up to 600 people. Let us create the perfect A1 atmosphere for your Christmas party. 020 7920 8613 . www.onemoorgateplace.com/christmas2015 CIRQUE LE SOIR Since our inception in 2009, Cirque le Soir has perfected the immersive experience. From events within our venue to hosting the Cirque experience A2 in other event spaces, we can bring a Cirque party to you! 020 7287 8001 . www.cirquelesoir.com/london/corporate BEST PARTIES EVER GROUP Best Parties Ever are the UK’s Leading Christmas Party Supplier, entertaining 170,000 guests at 21 venues including Tobacco Dock. Let us A3 indulge, amaze and excite you with an unforgettably magical experience. 0844 499 4040 . www.bestpartiesever.com D&D LONDON D&D London is a leading restaurant brand with a portfolio of over 30 venues in London, Leeds, Paris, New York and Tokyo. Group bookings, A4 private dining, terrace hire, exclusive hire, we do it all! Come see us. 020 7716 0716 . www.danddlondon.com/events HARBOUR & JONES EVENTS Current Event Caterer of the Year - Harbour & Jones Events caters events of every size and style. Our Event Team can help you plan a truly memorable A5 Christmas event in one of our many unique London venues. -

With the London Pass Entry Fee Entry Fee TOP ATTRACTIONS Tower of London + Fast Track Entrance £22.00 £10.00 Westminster Abbey £20.00 £9.00

London Pass Prices correct at 01.04.15 Attraction Entrance Prices FREE ENTRY to the following attractions Normal Adult Normal Child with the London Pass Entry fee Entry fee TOP ATTRACTIONS Tower of London + Fast track entrance £22.00 £10.00 Westminster Abbey £20.00 £9.00 NEW 1 Day Hop on Hop off Bus tour (From 1st October 2015) £22.00 £10.00 Windsor Castle + Fast track entrance £19.20 £11.30 Kensington Palace and The Orangery + Fast track entrance £15.90 FREE Hampton Court Palace + Fast track entrance £17.50 £8.75 17.10 ZSL London Zoo + Fast track entrance £24.30 Under 3 FREE Shakespeare's Globe Theatre Tour & Exhibition £13.50 £8.00 Churchill War Rooms £16.35 £8.15 London Bridge Experience and London Tombs + Fast track entrance £24.00 £18.00 Thames River Cruise £18.00 £9.00 HISTORIC BUILDINGS Tower Bridge Exhibition £9.00 £3.90 Royal Mews £9.00 £5.40 Royal Albert Hall - guided tour £12.25 £5.25 Royal Observatory £7.70 £3.60 Monument £4.00 £2.00 Banqueting House £6.00 FREE Jewel Tower £4.20 £2.50 Wellington Arch £4.30 £2.60 Apsley House £8.30 £5.00 Benjamin Franklin House £7.00 FREE Eltham Palace £13.00 £7.80 The Wernher Collection at Ranger's house £7.20 £4.30 MUSEUMS Imperial War Museum £5.00 £5.00 The London Transport Museum £16.00 FREE Household Cavalry Museum £7.00 £5.00 Charles Dickens Museum £8.00 £4.00 London Motor Museum £30.00 £20.00 Guards Museum £6.00 FREE Cartoon Museum £7.00 FREE Foundling Museum £7.50 FREE Science Museum - IMAX Theatre £11.00 £9.00 Handel House Museum £6.50 £2.00 London Canal Museum £4.00 £2.00 Royal Air -

PARK DESIGN GUIDE 2018 Drafts 1 and 2 Prepared by Draft 3 and 4 Prepared By

PARK DESIGN GUIDE 2018 Drafts 1 and 2 prepared by Draft 3 and 4 prepared by November 2017 January 2018 Draft Originated Checked Reviewed Authorised Date 1 for client review GW/RW/LD JR/GW NH HS 22/09/17 2 for final submission (for GW RW SJ HS 10/11/17 internal LLDC use) 3 for consultation AM/RH RH 24/11/17 4 final draft AM/RH RH LG 24/09/18 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 USER GUIDE 6 STREET FURNITURE STRATEGIC GUIDANCE STREET FURNITURE OVERVIEW 54 SEATING 55 PLAY FURNITURE 64 VISION 8 BOUNDARY TREATMENTS 66 INCLUSIVE DESIGN 9 PLANTERS 69 RELEVANT POLICIES AND GUIDANCE 10 BOLLARDS 70 GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE AND BIODIVERSITY 12 LIGHTING 72 HERITAGE AND CONSERVATION 14 PUBLIC ART 74 VENUE MANAGEMENT 15 REFUSE AND RECYCLING FACILITIES 75 SAFETY AND SECURITY 16 WAYFINDING 76 TRANSPORT INFRASTRUCTURE 17 CYCLE PARKING 80 TEMPORARY AND MOVEABLE FURNITURE 82 CHARACTER AREA DESIGN PRINCIPLES OTHER MISCELLANEOUS FURNITURE 84 QUEEN ELIZABETH OLYMPIC PARK 22 LANDSCAPE AND PLANTING NORTH PARK 23 SOUTH PARK 24 LANDSCAPE SPECIFICATION GUIDELINES 88 CANAL PARK 25 NORTH PARK 90 KEY DESIGN PRINCIPLES 26 SOUTH PARK 95 TREES 108 SURFACE MATERIALS SOIL AND EARTHWORKS 113 SUSTAINABLE DRAINAGE SYSTEMS (SUDS) 116 STANDARD MATERIALS PALETTE 30 WATERWAYS 120 PLAY SPACES 31 FOOTPATHS 34 CONSTRUCTION DESIGN AND MANAGEMENT FOOTWAYS 38 CARRIAGEWAYS 40 PARK OPERATIONS AND DESIGN MANAGEMENT 126 KERBS AND EDGING 42 RISK MANAGEMENT 127 SLOPES, RAMPS AND STEPS 45 CONSTRUCTION PLANNING AND MITIGATION 128 DRAINAGE 47 ASSET MANAGEMENT 129 PARKING AND LOADING 49 A PARK FOR THE FUTURE 130 UTILITIES 51 SURFACE MATERIALS MAINTENANCE 52 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS GLOSSARY REFERENCES QUEEN ELIZABETH OLYMPIC PARK DESIGN GUIDE INTRODUCTION CONTEXT Occupying more than 100ha, Queen Elizabeth Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park Estate is made Olympic Park lies across the border of four up of development plots which are defined East London boroughs: Hackney, Newham, by Legacy Communities Scheme (LCS). -

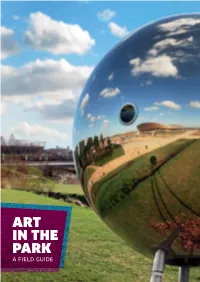

Art in the Park a FIELD GUIDE a Field Guide to Art in the Park 2 3 USING THIS GUIDE

1 ART IN THE PARK A FIELD GUIDE A FIELD GUIDE TO ART IN THE paRK 2 3 USING THIS GUIDE Queen Elizabeth Olympic This book is a field guide to the 26 permanent artworks in the Park. There’s a map at the back and Park was the first Olympic each artwork has a number to help you locate them. Going to find the artworks is just as important as all Park to integrate artworks the reading and looking you can do here. into the landscape right from These artworks have been made to be experienced the start. We worked with in the landscape – up close and from afar. Touch them, sit inside them, run across them, walk beneath established and emerging them. Gaze up, make games, take photographs, put artists, international and local, yourself in their shadow. to create an ambitious, diverse art programme that reflects the Park’s identity as a place for people from around the world and around the corner. Some of these artworks are large and striking, while others are smaller and harder to find. All of them were created specifically for this Park by contemporary artists who worked closely with the architects, designers and construction teams to develop and install their works. Their inspirations are varied: the undulating landscape, buried histories, community memories, song titles, flowing water, energy, ideas of shelter and discovery. Yet all of them are rooted here, each of them sparking new conversations with their immediate environment and this richly textured part of east London. “The trees mark time, the rings 2 3trace landscapes and lives that HistORY TREES have gone before.” Ackroyd and Harvey Ackroyd and Harvey British artists Ackroyd and Harvey created a series of living artworks to mark the main entrances of the Park. -

Gibbs Farm Kaipara Harbour, New Zealand

GIBBS FARM KAIPARA HARBOUR, NEW ZEALAND Seeing the Landscape the largest the artists have ever done. In response to the Rob Garrett demanding landscape, the artists have pushed beyond what they have previously attempted or achieved. ‘Then we end up having to make the works,’ says Gibbs, ‘and Commissioning new works rather than buying from an we particularly enjoy the challenge of making something exhibition has the satisfaction of dealing with the artists; that no one’s ever done before and solving the engineering and Alan Gibbs comments, ‘they’re interesting because problems to get there.’ Nevertheless, while the art is they’re winners; tough, ambitious’. a major source of stimulation for Gibbs, it has to share a place with his amphibian business, the land itself and When Alan Gibbs purchased his Kaipara property in 1991, his wanderlust, which has recently taken him to 160 he already had three decades of signifi cant art collecting countries, most by helicopter; and the place occupied behind him. Commissioning art works was in the back by the art at any one time depends on Gibbs’ need for a of his mind ‘but not the major purpose’ of searching for stimulus and whether the proposals under consideration a rural retreat. Looking back, it is clear now that 1991 are exciting enough. marked the beginning of a whole new art-collecting adventure for Gibbs; and it is one where it has been After nearly twenty years Gibbs’ collection includes major possible to be very, very ambitious. ‘We push the limits,’ works by Andy Goldsworthy, Anish Kapoor, Bill Culbert, Gibbs says. -

200 2 Willow Road 157 10 Downing Street 35 Abbey Road Studios 118

200 index 2 Willow Road 157 Fifty-Five 136 10 Downing Street 35 Freedom Bar 73 Guanabara 73 A Icebar 112 Abbey Road Studios 118 KOKO 137 Accessoires 75, 91, 101, 113, 129, 138, Mandarin Bar 90 Ministry of Sound 63 147, 162 Oliver’s Jazz Bar 155 Admiralty Arch 29 Portobello Star 100 Aéroports Princess Louise 83 London Gatwick Airport 171 Proud Camden 137 London Heathrow Airport 170 Purl 120 Afternoon tea 110 Salt Whisky Bar 112 Albert Memorial 88 She Soho 73 Alimentation 84, 101, 147 Shochu Lounge 83 Ambassades de Kensington Palace Simmon’s 83 Gardens 98 The Commercial Tavern 146 Antiquités 162 The Craft Beer Co. 73 Apsley House 103 The Dublin Castle 137 ArcelorMittal Orbit 166 The George Inn 63 Argent 186 The Mayor of Scaredy Cat Town 147 Artisanat 162 The Underworld 137 Auberges de jeunesse 176 Up the Creek Comedy Club 155 Vagabond 84 B Battersea Park 127 Berwick Street 68 Bank of England Museum 44 Big Ben 36 Banques 186 Bloomsbury 76 Banqueting House 34 Bond Street 108 Barbican Centre 51 Boris Bikes 185 Bars et boîtes de nuit 187 Borough Market 61 Admiral Duncan 73 Boxpark 144 Bassoon 39 Brick Lane 142 Blue Bar 90 British Library 77 BrewDog 136 Bunga Bunga 129 British Museum 80 Callooh Callay 146 Buckingham Palace 29 Cargo 146 Bus à impériale 184 Churchill Arms 100 Duke of Hamilton 162 C fabric 51 Cadeaux 39, 121, 155 http://www.guidesulysse.com/catalogue/FicheProduit.aspx?isbn=9782765826774 201 Cadogan Hall 91 Guy Fawkes Night 197 Camden Market 135 London Fashion Week 194, 196 Camden Town 130 London Film Festival 196 Cenotaph, The 35 London Marathon 194 Centres commerciaux 51, 63 London Restaurant Festival 196 Charles Dickens Museum 81 New Year’s Day Parade 194 Cheesegrater 40 New Year’s Eve Fireworks 197 Chelsea 122 Notting Hill Carnival 196 Pearly Harvest Festival 196 Chelsea Flower Show 195 Six Nations Rugby Championship 194 Chelsea Physic Garden 126 St.