Print/Download This Article (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ACTS BATTLE AFRICA HUNGER Upset Video Wholesalers to Country, Classical, Jazz and Dance

SM 14011 01066048024BB MAR86 ILL IONTY GREENLY 03 10 Foreigner, Bailey & Wham! 3740 ELM L. CV LONG BEACI CA 90807 jump to top 10 z See page 64 Bruce is back on top of Pop Albums See page 68 Fall Arbitron Ratings r See [urge 14 VOLUME 97 NO. 3 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT JANUARY 19, 1985/$3.50 (U.S.) Richie Enlists US. Superstars WEA Dealer Discounts ACTS BATTLE AFRICA HUNGER Upset Video Wholesalers to country, classical, jazz and dance. Kenny Rogers. BY PAUL GREIN But the project being coordinated Kragen will produce the event, Under the new pricing structure, LOS ANGELES Lionel Richie and by Richie and Kragen may raise the which will likely include both an al- BY FAYE ZUCKERMAN distributors will still pay WEA his manager Ken Kragen are spear- most money for African relief, be- bum and subsequent singles and a LOS ANGELES Nearly a week af- about $50 for a $79.98 title, while re- heading a multi -media event, to be cause of the magnitude of the talent live show with worldwide transmis- ter Warner Home Video's revamped tailers will start to pay just over $52 held here in the next two weeks, to involved. While no names have yet sion. The details, which were still pricing schedules and stock balanc- for the same title. "We generally continue industry efforts to raise been announced, it's believed that being set at presstime, are expected ing program went into effect, video sell [WEA] $79.98 cassettes to re- money for the starving in Africa. -

A Treatise on Diamonds and Pearls

w^miss ^i §m j)d~ 2±- aSgECESgEC'^eSCX^?2r. ^.KSQfOSggeGSSOs The Robert E. Gross Collection A Memorial to the Founder of the ten Business Administration Library Los Angeles 7 : TRE ATI SE 3 O N DIAMONDS and PEARLS. I N W H I C H Their Importance is confidered : AND Plain Rules are exhibited for afcertaining the Value of both AND THE True Method of manufaduring Diamonds. By DA FI D JEFFRIES, JEWELLER. The Second Edition, with large Improvements. LONDON: Printed by C. and J. Ac k e r s, in St. Jobn'i.Sireef, For the AU THOR. 1751. (Price 2 /Z Guinea Bound.) . •• 5 i^i^^ Dedication. and juftice, and friend to the common jntereft of mankind, more particularly to that of your Majefifs fubje£l:s : In which your royal character fhines with the brighteft luftre. It contains rational and plain rules for eftimating the value of Diamonds and Pearls under all circumftances, and for manufac- turing Diamonds to the greateft perfection ; Both which have hitherto been but very imper- fe6lly underftood. From hence, all property of this kind has been expofed to the greateft injur)-, D ED I C AT I O N. injury, by being fubjeit to a capricious and indeterminate va- luation 5 and the fuperlative beauty of Diamonds has been much debafcd. To countenance a work cal- culated to promote a general be- nefit, it is humbly apprehended, will not be deemed unworthy the condefcenfion of a Crowned Head, as thele Jewels conftitute fo large a part ofpublick wealth; and, as they are, and have been inpaft ages, the chief or- naments of great and diftin- guilhed perfonages, in moil parts of the world. -

Prince 20Ten Complete European Summer Tour Recordings Vol

Prince 20Ten Complete European Summer Tour Recordings Vol. 10 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Funk / Soul / Pop Album: 20Ten Complete European Summer Tour Recordings Vol. 10 Country: Germany MP3 version RAR size: 1482 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1272 mb WMA version RAR size: 1410 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 916 Other Formats: VOC WAV AUD MOD TTA AAC DXD Tracklist Yas Arena, Yas Island, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, November 14, 2010 1-1 Let's Go Crazy 1-2 Delirious 1-3 Let's Go Crazy (Reprise) 1-4 1999 1-5 Little Red Corvette 1-6 Controversy / Oh Abu Dhabi (Chant) 1-7 Sexy Dancer / Le Freak 1-8 Controversy (Coda) / Housequake (Chant) 1-9 Angel 1-10 Nothing Compares 2 U 1-11 Uptown 1-12 Raspberry Beret 1-13 Cream (Includes For Love) 1-14 U Got The Look 1-15 Shhh 1-16 Love...Thy Will Be Done 1-17 Keyboard Interlude 1-18 Purple Rain 2-1 Kiss 2-2 Prince And The Girls Pick Some Dancers 2-3 The Bird 2-4 Jungle Love 2-5 A Love Bizarre (Aborted) 2-6 A Love Bizarre (Nicole Scherzinger On Co-Lead Vocals) 2-7 Dance (Disco Heat) 2-8 Baby I'm A Star 2-9 Sometimes It Snows In April 2-10 Peach Soundcheck, Gelredome, Arnhem, November 18, 2010 2-11 Scandalous / The Beautiful Ones (Instrumental Takes) 2-12 The Beautiful Ones (Various Instrumental Takes) 2-13 Nothing Compares 2 U (3 Instrumental Takes) 2-14 Car Wash (Instrumental Groove) / Controversy (Instrumental) 2-15 Hot Thing (Extended Jam, Overmodulated) 2-16 Hot Thing (Extended Jam, Clean Part) 2-17 Flashlight (Instrumental) 2-18 Insatiable 2-19 Insatiable / If I Was Your Girlfriend -

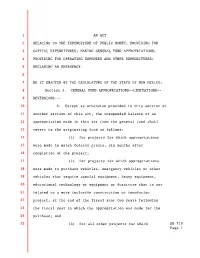

Senate Bill Text for SB0710

1 AN ACT 2 RELATING TO THE EXPENDITURE OF PUBLIC MONEY; PROVIDING FOR 3 CAPITAL EXPENDITURES; MAKING GENERAL FUND APPROPRIATIONS; 4 PROVIDING FOR OPERATING EXPENSES AND OTHER EXPENDITURES; 5 DECLARING AN EMERGENCY. 6 7 BE IT ENACTED BY THE LEGISLATURE OF THE STATE OF NEW MEXICO: 8 Section 1. GENERAL FUND APPROPRIATIONS--LIMITATIONS-- 9 REVERSIONS.-- 10 A. Except as otherwise provided in this section or 11 another section of this act, the unexpended balance of an 12 appropriation made in this act from the general fund shall 13 revert to the originating fund as follows: 14 (1) for projects for which appropriations 15 were made to match federal grants, six months after 16 completion of the project; 17 (2) for projects for which appropriations 18 were made to purchase vehicles, emergency vehicles or other 19 vehicles that require special equipment, heavy equipment, 20 educational technology or equipment or furniture that is not 21 related to a more inclusive construction or renovation 22 project, at the end of the fiscal year two years following 23 the fiscal year in which the appropriation was made for the 24 purchase; and 25 (3) for all other projects for which SB 710 Page 1 1 appropriations were made, within six months of completion of 2 the project, but no later than the end of fiscal year 2011. 3 B. Upon certification by an agency that money from 4 the general fund is needed for a purpose specified in this 5 act, the secretary of finance and administration shall 6 disburse such amount of the appropriation for that project as 7 is necessary to meet that need. -

Activities Guide

Fall 2018 Activities Guide ¡Con información esencial traducida al español! (páginas 10-18) YOUTH & ADULT Programs | Activities Events thprd.org Celebrate with us! Whether it’s a birthday, graduation, meeting, retreat or other event, find the perfect THPRD space to rent for your next celebration. Picnic Shelters Meetings & Classrooms AM Kennedy Park Cedar Hills Recreation Center Barsotti Park Conestoga Recreation & Aquatic Camille Park Center Cedar Hills Park Elsie Stuhr Center Jackie Husen Park Garden Home Recreation Center Raleigh Park Howard M. Terpenning Schiffler Park Recreation Complex Tualatin Hills Nature Center Specialty & Swim Aloha Swim Center Beaverton Swim Center Cedar Hills Recreation Center Conestoga Recreation & Aquatic Center Garden Home Recreation Center Harman Swim Center Tualatin Hills Aquatic Center Tualatin Hills Nature Center Sunset Swim Center Learn more at thprd.org/facilities or call 503-645-6433 CCC report a call to action for all to embrace equity Greetings from your elected board of directors! In June, the Coalition of Communities of Color released a landmark report on racial inequity in Washington County. The report – based on a two-year Table of Contents study funded in part by THPRD – focused on the very real challenges experienced by eight communities of color that collectively comprise one-third of all people living in THPRD Facilities and Map ..................... 2-3 the county. Registration Information ....................... 4-5 The populations highlighted are, in Drop-in Programs and Daily order of size: Latino, Asian and Asian Admissions .......................................... 6 American, African American, Slavic/ THPRD Scholarship Program .................... 8 Russian, Native American, Middle Eastern/North African, Hawaiian Volunteering at THPRD ............................ 9 and Pacifi c Islander, and African. -

Prince All Albums Free Download Hitnrun: Phase Two

prince all albums free download HITnRUN: Phase Two. Following quickly on the heels of its companion, HITnRUN: Phase Two is more a complement to than a continuation of its predecessor. Prince ditches any of the lingering modern conveniences of HITnRUN: Phase One -- there's nary a suggestion of electronics and it's also surprisingly bereft of guitar pyrotechnics -- in favor of a streamlined, even subdued, soul album. Despite its stylistic coherence, Prince throws a few curve balls, tossing in a sly wink to "Kiss" on "Stare" and opening the album with "Baltimore," a Black Lives Matter protest anthem where his outrage is palpable even beneath the slow groove. That said, even the hardest-rocking tracks here -- that would be the glammy "Screwdriver," a track that would've been an outright guitar workout if cut with 3rdEyeGirl -- is more about the rhythm than the riff. Compared to the relative restlessness of HITnRUN: Phase One, not to mention the similarly rangy Art Official Age, this single-mindedness is initially overwhelming but like any good groove record, HITnRUN: Phase Two winds up working best over the long haul, providing elegant, supple mood music whose casualness plays in its favor. Prince isn't showing off, he's settling in, and there are considerable charms in hearing a master not trying so hard. Prince all albums free download. © 2021 Rhapsody International Inc., a subsidiary of Napster Group PLC. All rights reserved. Napster and the Napster logo are registered trademarks of Rhapsody International Inc. Napster. Music Apps & Devices Blog Pricing Artist & Labels. About Us. Company Info Careers Developers. -

What's Next for the Artist?

two unreal albums in the span of a week... What’s next for the artist? Future’smay prove to be his‘HNDRXX’ masterpiece photo by Arkady Lifshits Our take on the rapper/singer’s second LP of 2017 cover photo by: The Come Up Show By Jeff Weiss Long before the lawsuits and the line of cowboy hats, crossover attempts, and a song with Kanye West com- ue by several million. Ciara and his old business partner Just one week after dropping a one-note self-titled album, the mixtape run, mainstream worship, and enough co- paring their greatest loves to lifeless golden statuettes. Rocko sued him. Russell Wilson got hexed by the curse Future f***** around and dropped what may prove to be his deine, perkys, and molly to throttle every glowsticked Sales bricked, Ciara and Future split, and the industry of Big Rube. And no one will ever look at a Gucci flip-flop masterpiece. HNDRXX is the highest incarnation of Future: bro at the Electric Daisy Carnival, Future planned to briefly exiled him to the no service purgatory where they the same way again. that alchemy of joy, drugs, and pain that makes you unsure follow up his debut Pluto with an album called Hendrix. stash Yelawolf. whether you want to cry or celebrate—probably both. It’s Then it looked like history might repeat itself. Last year’s as if Future realized that the best records he ever wrote In the interest of originality and delineating himself You know what happened next. Atlanta’s Nayvadius Wil- Purple Reign and Evol lacked carbonation—as though were “Codeine Crazy,” “You Deserve It,” “Body Party,” and from one of the first music legends to take acid and feel burn transformed into the monster, embarking on the Future had mastered the art of making #trapbangers the first draft of “Drunk in Love.” This album is crystallized good, Future eventually switched the title to Honest. -

Features Lifestyle

12 Established 1961 Lifestyle Features Monday, July 26, 2021 rince’s estate will soon issue a sciousness... this is a concerted effort to technology and devices, which he saw the first time. “He said, ‘never in my completed record from the mercuri- really speak about these things,” said “as something that handcuffed people.” career have I taken a week where I didn’t Pal artist’s storied music vault, the Hayes, who co-produced the album. “I But while the album tackles decidedly write a song and pick up my guitar.’” The first never-before-heard album released really dug how raw it was, and as far as weighty topics - “Running Game (Son of release of Prince’s vast trove of music since the musician’s shock death five my production, I just wanted to keep it to a Slave Master)” centers on racism, remains a sensitive subject; the super- years ago. “Welcome 2 America” - a 12- where its raw and I don’t get in the way while “Same Page, Different Book” star was controlling of his work, image, track album finished in 2010, but shelved of what he’s trying to say.” touches on religious strife - the album and carefully constructed enigmatic per- for reasons unknown in the famous vault also includes vintage danceable and car- sona. Doing right by him is no small chal- at Prince’s Paisley Park compound near ‘Liberty and justice’ nal slow jam Prince in the mix. “Hot lenge. Minneapolis - offers a prophetic window For Hayes, the singular artist “was Summer” is a major-key, guitar-heavy, Previously the estate has re-released into social struggles at today’s forefront, way ahead”, like a “sage sitting in the feel-good track, while the sparsely expanded versions of Prince’s milestone delving into racism, political division, Himalayas somewhere”, in foreshadow- arranged “When She Comes” featuring albums, like “1999” and “Sign O’ The technology and disinformation. -

Prince Playlist Questions As You Watch and Listen to the Prince Playlist, Try to Answer Each of the Below Questions

Prince Playlist Questions As you watch and listen to the Prince playlist, try to answer each of the below questions. Pause between videos to read the question so that you can keep it in mind as you enjoy the video. Some questions may require outside research. “Baby, I’m a Star” Live (Official Music Video) Prince stops and resumes this song repeatedly. How many times does this happen? Prince and the New Power Generation, “Willing and Able,” (Official Music Video) This song begins with an electric guitar that sounds like classic rock and roll. What other musical genres do you hear in “Willing and Able”? “Sometimes It Snows in April” (Live at Webster Hall, April 20, 2004) “Sometimes It Snows in April” is a song from the soundtrack of Under the Cherry Moon, Prince’s film of the same name. Based on the lyrics and sound of this song, what sort of movie do you imag- ine Under the Cherry Moon might be? (Ex. action, mystery, etc.) At the beginning of the video Prince plays excerpts of two R&B songs by iconic women vocalists. The songs are “Sweet Thing” and “Proud Mary”. Who are the two artists who recorded them? “Strollin’/ U Want Me” (Live At The Aladdin, December 15, 2002) There are elements of this performance that can be described as Jazz. What are they? List at least two. “Call My Name” (Official Music Video) This video suggests that “Call My Name” is appropriate for a social celebration. What is the occasion dramatized in this video? “When Will We B Paid?” (Staple Singers Cover) November 11, 2001 What is the lyrical theme of this cover of the song by The Staple Singers, originally released in 1970? “Diamonds and Pearls” (Official Music Video) Both Prince and Rosie Gaines, the vocalist featured on this duet, are shown playing the same instru- ment. -

United in Victory Toledo-Winlock Soccer Team Survives Dameon Pesanti / [email protected] Opponents of Oil Trains Show Support for a Speaker Tuesday

It Must Be Tigers Bounce Back Spring; The Centralia Holds Off W.F. West 9-6 in Rivalry Finale / Sports Weeds are Here / Life $1 Midweek Edition Thursday, May 1, 2014 Reaching 110,000 Readers in Print and Online — www.chronline.com United in Victory Toledo-Winlock Soccer Team Survives Dameon Pesanti / [email protected] Opponents of oil trains show support for a speaker Tuesday. Oil Train Opponents Dominate Centralia Meeting ONE-SIDED: Residents Fear Derailments, Explosions, Traffic Delays By Dameon Pesanti [email protected] More than 150 people came to Pete Caster / [email protected] the Centralia High School audito- Toledo-Winlock United goalkeeper Elias delCampo celebrates after leaving the Winlock School District meeting where the school board voted to strike down the rium Tuesday night to voice their motion to dissolve the combination soccer team on Wednesday evening. concerns against two new oil transfer centers slated to be built in Grays Harbor. CELEBRATION: Winlock School Board The meeting was meant to be Votes 3-2 to Keep Toledo/Winlock a platform for public comments and concerns related to the two Combined Boys Soccer Program projects, but the message from attendees was clear and unified By Christopher Brewer — study as many impacts as pos- [email protected] sible, but don’t let the trains come WINLOCK — United they have played for nearly through Western Washington. two decades, and United they will remain for the Nearly every speaker ex- foreseeable future. pressed concerns about the Toledo and Winlock’s combined boys’ soccer increase in global warming, program has survived the chopping block, as the potential derailments, the unpre- Winlock School Board voted 3-2 against dissolving paredness of municipalities in the the team at a special board meeting Wednesday eve- face of explosions and the poten- ning. -

Çž‹Å(Éÿ³æ¨‚Å®¶) Éÿ³æ¨‚Å°ˆè¼¯ ĸ²È¡Œ (ĸ“Ⱦ' & Æ—¶É— ´È¡¨)

王å (音樂家) 音樂專輯 串行 (专辑 & æ—¶é— ´è¡¨) The Black Album https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-black-album-880043/songs Lovesexy https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/lovesexy-1583377/songs Love Symbol https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/love-symbol-955274/songs Graffiti Bridge https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/graffiti-bridge-2006389/songs Musicology https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/musicology-592659/songs The Rainbow Children https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-rainbow-children-1889451/songs 3121 https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/3121-224638/songs Chaos and Disorder https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/chaos-and-disorder-2956463/songs 20Ten https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/20ten-1755769/songs Plectrumelectrum https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/plectrumelectrum-18193229/songs N.E.W.S https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/n.e.w.s-1583349/songs Art Official Age https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/art-official-age-18085760/songs One Nite Alone... https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/one-nite-alone...-2231221/songs HITnRUN Phase Two https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/hitnrun-phase-two-21762471/songs The Vault: Old Friends 4 Sale https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-vault%3A-old-friends-4-sale-2633846/songs https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/hitnrun-phase-one-%28prince-album%29- HITnRUN phase one (Prince album) 20735574/songs The Chocolate Invasion https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-chocolate-invasion-1975542/songs -

085765096700 Hd Movies / Game / Software / Operating System

085765096700 --> SMS / CHAT ON / WHATSAPP / LINE HD MOVIES / GAME / SOFTWARE / OPERATING SYSTEM / EBOOK VIDEO TUTORIAL / ANIME / TV SERIAL / DORAMA / HD DOKUMENTER / VIDEO CONCERT Pertama-tama saya ucapkan terimaksih agan2 yang telah mendownload list ini.. Harap di isi dan kirim ke [email protected] Isi data : NAMA : ALAMAT : NO HP : HARDISK : TOTAL KESELURUHAN PENGISIAN HARDISK : Untuk pengisian hardisk: 1. Tinggal titipkan hardisk internal/eksternal kerumah saya dari jam 07:00-23:00 WIB untuk alamat akan saya sms.. 2. List pemesanannya di kirim ke email [email protected]/saat pengantar hardisknya jg boleh, bebas pilih yang ada di list.. 3. Pembayaran dilakukan saat penjemputan hardisk.. 4. Terima pengiriman hardisk, bagi yang mengirimkan hardisknya internal dan external harap memperhatikan packingnya.. Untuk pengisian beserta hardisknya: 1. Transfer rekening mandiri, setelah mendapat konfirmasi transfer, pesanan baru di proses.. 2. Hardisk yang telah di order tidak bisa di batalkan.. 3. Pengiriman menggunakan jasa Jne.. 4. No resi pengiriman akan di sms.. Lama pengerjaan 1 - 4 hari tergantung besarnya isian dan antrian tapi saya usahakan secepatnya.. Harga Pengisian Hardisk : Dibawah Hdd320 gb = 50.000 Hdd 500 gb = 70.000 Hdd 1 TB =100.000 Hdd 1,5 TB = 135.000 Hdd 2 TB = 170.000 Yang memakai hdd eksternal usb 2.0 kena biaya tambahan Check ongkos kirim http://www.jne.co.id/ BATAM GAME 085765096700 --> SMS / CHAT ON / WHATSAPP / LINE HD MOVIES / GAME / SOFTWARE / OPERATING SYSTEM / EBOOK VIDEO TUTORIAL / ANIME / TV SERIAL / DORAMA / HD DOKUMENTER / VIDEO CONCERT Pertama-tama saya ucapkan terimaksih agan2 yang telah mendownload list ini.. Movies 0 GB Game Pc 0 GB Software 0 GB EbookS 0 GB Anime dan Concert 0 GB 3D / TV SERIES / HD DOKUMENTER 0 GB TOTAL KESELURUHAN 0 GB 1.