“You Can of Course Keep Shaking the Box”: Errant Versioning and Textual Motion in the Iterations of Anne Carson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Golden Gorgon-Medousa Artwork in Ancient Hellenic World

SCIENTIFIC CULTURE, Vol. 5, No. 1, (2019), pp. 1-14 Open Access. Online & Print DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.1451898 GOLDEN GORGON-MEDOUSA ARTWORK IN ANCIENT HELLENIC WORLD Lazarou, Anna University of Peloponnese, Dept of History, Archaeology and Cultural Resources Management Palaeo Stratopedo, 24100 Kalamata, Greece ([email protected]; [email protected]) Received: 15/06/2018 Accepted: 25/07/2018 ABSTRACT The purpose of this research is to highlight some characteristic examples of the golden works depicting the gorgoneio and Gorgon. These works are part of the wider chronological and geographical context of the ancient Greek world. Twenty six artifacts in total, mainly jewelry, as well as plates, discs, golden bust, coins, pendant and a vial are being examined. Their age dates back to the 6th century. B.C. until the 3rd century A.D. The discussion is about making a symbol of the deceased persist for long in the antiquity and showing the evolution of this form. The earliest forms of the Gorgo of the Archaic period depict a monster demon-like bellows, with feathers, snakes in the head, tongue protruding from the mouth and tusks. Then, in classical times, the gorgonian form appears with human characteristics, while the protruded tusks and the tongue remain. Towards Hellenistic times and until late antiquity, the gorgoneion has characteristics of a beautiful woman. Snakes are the predominant element of this gorgon, which either composes the gargoyle's hairstyle or is plundered like a jewel under its chin. This female figure with the snakes is interwoven with Gorgo- Medusa and the Perseus myth that had a wide reflection throughout the ancient times. -

Greek Myths - Creatures/Monsters Bingo Myfreebingocards.Com

Greek Myths - Creatures/Monsters Bingo myfreebingocards.com Safety First! Before you print all your bingo cards, please print a test page to check they come out the right size and color. Your bingo cards start on Page 3 of this PDF. If your bingo cards have words then please check the spelling carefully. If you need to make any changes go to mfbc.us/e/xs25j Play Once you've checked they are printing correctly, print off your bingo cards and start playing! On the next page you will find the "Bingo Caller's Card" - this is used to call the bingo and keep track of which words have been called. Your bingo cards start on Page 3. Virtual Bingo Please do not try to split this PDF into individual bingo cards to send out to players. We have tools on our site to send out links to individual bingo cards. For help go to myfreebingocards.com/virtual-bingo. Help If you're having trouble printing your bingo cards or using the bingo card generator then please go to https://myfreebingocards.com/faq where you will find solutions to most common problems. Share Pin these bingo cards on Pinterest, share on Facebook, or post this link: mfbc.us/s/xs25j Edit and Create To add more words or make changes to this set of bingo cards go to mfbc.us/e/xs25j Go to myfreebingocards.com/bingo-card-generator to create a new set of bingo cards. Legal The terms of use for these printable bingo cards can be found at myfreebingocards.com/terms. -

Hesiod Theogony.Pdf

Hesiod (8th or 7th c. BC, composed in Greek) The Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, are probably slightly earlier than Hesiod’s two surviving poems, the Works and Days and the Theogony. Yet in many ways Hesiod is the more important author for the study of Greek mythology. While Homer treats cer- tain aspects of the saga of the Trojan War, he makes no attempt at treating myth more generally. He often includes short digressions and tantalizes us with hints of a broader tra- dition, but much of this remains obscure. Hesiod, by contrast, sought in his Theogony to give a connected account of the creation of the universe. For the study of myth he is im- portant precisely because his is the oldest surviving attempt to treat systematically the mythical tradition from the first gods down to the great heroes. Also unlike the legendary Homer, Hesiod is for us an historical figure and a real per- sonality. His Works and Days contains a great deal of autobiographical information, in- cluding his birthplace (Ascra in Boiotia), where his father had come from (Cyme in Asia Minor), and the name of his brother (Perses), with whom he had a dispute that was the inspiration for composing the Works and Days. His exact date cannot be determined with precision, but there is general agreement that he lived in the 8th century or perhaps the early 7th century BC. His life, therefore, was approximately contemporaneous with the beginning of alphabetic writing in the Greek world. Although we do not know whether Hesiod himself employed this new invention in composing his poems, we can be certain that it was soon used to record and pass them on. -

"Dazzling Hybrids" the Poetry of Anne Carson

a n Rae "Dazzling Hybrids" The Poetry of Anne Carson The subtitle of A n n e Carson's Autobiography of Red: A Novel in Verse only hints at t h e variety of g e n r e s that the Montreal poet employs. In Autobiography of Red, Carson brings together seven distinct sec- tions—a "proemium" (6) o r preface on t h e Greek poet Stesichoros, trans- lated fragments of S t e s i c h o r o s ' s Geryoneis, three appendices on t h e blinding of Stesichoros by Helen, a l o n g romance-in-verse recasting Stesichoros's Geryoneis as a c o n t e m p o r a r y gay love affair, and a mock-interview with the "choir-master"—each with its o w n style and story to tell. Carson finds fresh combinations for g e n r e s much as s h e presents myth and gender in a new guise. Although men appear to b e t h e subject of both the romance and the academic apparatus that comes with it, C a r s o n sets the stories of Stesichoros, Geryon, and Herakles within a framework of e p i g r a m s and citations from Gertrude Stein and Emily Dickinson that, far from being subordinate, assumes equal importance with the male-centred narrative when Stein supplants Stesichoros in t h e concluding interview. The shift in speakers and time-frames in t h e interview, as well as the allusions to the myth of I s i s , emphasize Carson's manipulation of m y t h i c forms. -

MYTHOLOGY – ALL LEVELS Ohio Junior Classical League – 2012 1

MYTHOLOGY – ALL LEVELS Ohio Junior Classical League – 2012 1. This son of Zeus was the builder of the palaces on Mt. Olympus and the maker of Achilles’ armor. a. Apollo b. Dionysus c. Hephaestus d. Hermes 2. She was the first wife of Heracles; unfortunately, she was killed by Heracles in a fit of madness. a. Aethra b. Evadne c. Megara d. Penelope 3. He grew up as a fisherman and won fame for himself by slaying Medusa. a. Amphitryon b. Electryon c. Heracles d. Perseus 4. This girl was transformed into a sunflower after she was rejected by the Sun god. a. Arachne b. Clytie c. Leucothoe d. Myrrha 5. According to Hesiod, he was NOT a son of Cronus and Rhea. a. Brontes b. Hades c. Poseidon d. Zeus 6. He chose to die young but with great glory as opposed to dying in old age with no glory. a. Achilles b. Heracles c. Jason d. Perseus 7. This queen of the gods is often depicted as a jealous wife. a. Demeter b. Hera c. Hestia d. Thetis 8. This ruler of the Underworld had the least extra-marital affairs among the three brothers. a. Aeacus b. Hades c. Minos d. Rhadamanthys 9. He imprisoned his daughter because a prophesy said that her son would become his killer. a. Acrisius b. Heracles c. Perseus d. Theseus 10. He fled burning Troy on the shoulder of his son. a. Anchises b. Dardanus c. Laomedon d. Priam 11. He poked his eyes out after learning that he had married his own mother. -

CLARK PLANETARIUM SOLAR SYSTEM FACT SHEET Data Provided by NASA/JPL and Other Official Sources

CLARK PLANETARIUM SOLAR SYSTEM FACT SHEET Data provided by NASA/JPL and other official sources. This handout ©July 2013 by Clark Planetarium (www.clarkplanetarium.org). May be freely copied by professional educators for classroom use only. The known satellites of the Solar System shown here next to their planets with their sizes (mean diameter in km) in parenthesis. The planets and satellites (with diameters above 1,000 km) are depicted in relative size (with Earth = 0.500 inches) and are arranged in order by their distance from the planet, with the closest at the top. Distances from moon to planet are not listed. Mercury Jupiter Saturn Uranus Neptune Pluto • 1- Metis (44) • 26- Hermippe (4) • 54- Hegemone (3) • 1- S/2009 S1 (1) • 33- Erriapo (10) • 1- Cordelia (40.2) (Dwarf Planet) (no natural satellites) • 2- Adrastea (16) • 27- Praxidike (6.8) • 55- Aoede (4) • 2- Pan (26) • 34- Siarnaq (40) • 2- Ophelia (42.8) • Charon (1186) • 3- Bianca (51.4) Venus • 3- Amalthea (168) • 28- Thelxinoe (2) • 56- Kallichore (2) • 3- Daphnis (7) • 35- Skoll (6) • Nix (60?) • 4- Thebe (98) • 29- Helike (4) • 57- S/2003 J 23 (2) • 4- Atlas (32) • 36- Tarvos (15) • 4- Cressida (79.6) • Hydra (50?) • 5- Desdemona (64) • 30- Iocaste (5.2) • 58- S/2003 J 5 (4) • 5- Prometheus (100.2) • 37- Tarqeq (7) • Kerberos (13-34?) • 5- Io (3,643.2) • 6- Pandora (83.8) • 38- Greip (6) • 6- Juliet (93.6) • 1- Naiad (58) • 31- Ananke (28) • 59- Callirrhoe (7) • Styx (??) • 7- Epimetheus (119) • 39- Hyrrokkin (8) • 7- Portia (135.2) • 2- Thalassa (80) • 6- Europa (3,121.6) -

Stories and Essays on Persephone and Medusa Isabelle George Rosett Scripps College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2017 Voices of Ancient Women: Stories and Essays on Persephone and Medusa Isabelle George Rosett Scripps College Recommended Citation Rosett, Isabelle George, "Voices of Ancient Women: Stories and Essays on Persephone and Medusa" (2017). Scripps Senior Theses. 1008. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/1008 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOICES OF ANCIENT WOMEN: STORIES AND ESSAYS ON PERSEPHONE AND MEDUSA by ISABELLE GEORGE ROSETT SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR NOVY PROFESSOR BERENFELD APRIL 21, 2017 1 2 Dedicated: To Max, Leo, and Eli, for teaching me about surviving the things that scare me and changing the things that I can’t survive. To three generations of Heuston women and my honorary sisters Krissy and Madly, for teaching me about the ways I can be strong, for valuing me exactly as I am, and for the endless excellent desserts. To my mother, for absolutely everything (but especially for fielding literally dozens of phone calls as I struggled through this thesis). To Sam, for being the voice of reason that I happily ignore, for showing up with Gatorade the day after New Year’s shenanigans, and for the tax breaks. To my father (in spite of how utterly terrible he is at carrying on a phone conversation), for the hikes and the ski days, for quoting Yeats and Blake at the dinner table, and for telling me that every single essay I’ve ever asked him to edit “looks good” even when it was a blatant lie. -

(Self-) Portraits in the Work of John Berryman, John Ashbery, Anne Carson, and Nan Goldin

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2019 “Whispers Out of Time”: Memorializing (Self-) Portraits in the Work of John Berryman, John Ashbery, Anne Carson, and Nan Goldin Andrew D. King The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3185 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] “WHISPERS OUT OF TIME”: MEMORIALIZING (SELF-) PORTRAITS IN THE WORK OF JOHN BERRYMAN, JOHN ASHBERY, ANNE CARSON, AND NAN GOLDIN By ANDREW D. KING A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2019 © 2019 ANDREW D. KING All rights reserved ii “WHISPERS OUT OF TIME”: MEMORIALIZING (SELF-) PORTRAITS IN THE WORK OF JOHN BERRYMAN, JOHN ASHBERY, ANNE CARSON, AND NAN GOLDIN By Andrew D. King This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. Date George Fragopoulos Thesis Advisor Date Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT “Whispers Out of Time”: Memorializing (Self-)Portraits in the work of John Berryman, John Ashbery, Anne Carson, and Nan Goldin by Andrew D. King Advisor: George Fragopoulos This thesis documents four distinct post-WWII North American writers and artists—the poet John Berryman, the poet John Ashbery, the classicist and writer Anne Carson, and the photographer Nan Goldin—who expanded traditional definitions and practices of portraiture. -

Greek Mythology

Greek Mythology The Creation Myth “First Chaos came into being, next wide bosomed Gaea(Earth), Tartarus and Eros (Love). From Chaos came forth Erebus and black Night. Of Night were born Aether and Day (whom she brought forth after intercourse with Erebus), and Doom, Fate, Death, sleep, Dreams; also, though she lay with none, the Hesperides and Blame and Woe and the Fates, and Nemesis to afflict mortal men, and Deceit, Friendship, Age and Strife, which also had gloomy offspring.”[11] “And Earth first bore starry Heaven (Uranus), equal to herself to cover her on every side and to be an ever-sure abiding place for the blessed gods. And earth brought forth, without intercourse of love, the Hills, haunts of the Nymphs and the fruitless sea with his raging swell.”[11] Heaven “gazing down fondly at her (Earth) from the mountains he showered fertile rain upon her secret clefts, and she bore grass flowers, and trees, with the beasts and birds proper to each. This same rain made the rivers flow and filled the hollow places with the water, so that lakes and seas came into being.”[12] The Titans and the Giants “Her (Earth) first children (with heaven) of Semi-human form were the hundred-handed giants Briareus, Gyges, and Cottus. Next appeared the three wild, one-eyed Cyclopes, builders of gigantic walls and master-smiths…..Their names were Brontes, Steropes, and Arges.”[12] Next came the “Titans: Oceanus, Hypenon, Iapetus, Themis, Memory (Mnemosyne), Phoebe also Tethys, and Cronus the wily—youngest and most terrible of her children.”[11] “Cronus hated his lusty sire Heaven (Uranus). -

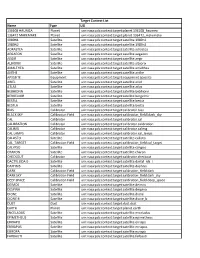

PDS4 Context List

Target Context List Name Type LID 136108 HAUMEA Planet urn:nasa:pds:context:target:planet.136108_haumea 136472 MAKEMAKE Planet urn:nasa:pds:context:target:planet.136472_makemake 1989N1 Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.1989n1 1989N2 Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.1989n2 ADRASTEA Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.adrastea AEGAEON Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.aegaeon AEGIR Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.aegir ALBIORIX Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.albiorix AMALTHEA Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.amalthea ANTHE Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.anthe APXSSITE Equipment urn:nasa:pds:context:target:equipment.apxssite ARIEL Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.ariel ATLAS Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.atlas BEBHIONN Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.bebhionn BERGELMIR Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.bergelmir BESTIA Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.bestia BESTLA Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.bestla BIAS Calibrator urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibrator.bias BLACK SKY Calibration Field urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibration_field.black_sky CAL Calibrator urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibrator.cal CALIBRATION Calibrator urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibrator.calibration CALIMG Calibrator urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibrator.calimg CAL LAMPS Calibrator urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibrator.cal_lamps CALLISTO Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.callisto -

Virtue Ethics and Education from Late Antiquity to the Eighteenth Century

KNOWLEDGE COMMUNITIES Hellerstedt (ed.) Hellerstedt Eighteenth Century the to Antiquity Late from Virtue Ethics and Education Edited by Andreas Hellerstedt Virtue Ethics and Education from Late Antiquity to the Eighteenth Century Virtue Ethics and Education from Late Antiquity to the Eighteenth Century Knowledge Communities This series focuses on innovative scholarship in the areas of intellectual history and the history of ideas, particularly as they relate to the communication of knowledge within and among diverse scholarly, literary, religious, and social communities across Western Europe. Interdisciplinary in nature, the series especially encourages new methodological outlooks that draw on the disciplines of philosophy, theology, musicology, anthropology, paleography, and codicology. Knowledge Communities addresses the myriad ways in which knowledge was expressed and inculcated, not only focusing upon scholarly texts from the period but also emphasizing the importance of emotions, ritual, performance, images, and gestures as modalities that communicate and acculturate ideas. The series publishes cutting-edge work that explores the nexus between ideas, communities and individuals in medieval and early modern Europe. Series Editor Clare Monagle, Macquarie University Editorial Board Mette Bruun, University of Copenhagen Babette Hellemans, University of Groningen Severin Kitanov, Salem State University Alex Novikofff, Fordham University Willemien Otten, University of Chicago Divinity School Virtue Ethics and Education from Late Antiquity -

A Dictionary of Mythology —

Ex-libris Ernest Rudge 22500629148 CASSELL’S POCKET REFERENCE LIBRARY A Dictionary of Mythology — Cassell’s Pocket Reference Library The first Six Volumes are : English Dictionary Poetical Quotations Proverbs and Maxims Dictionary of Mythology Gazetteer of the British Isles The Pocket Doctor Others are in active preparation In two Bindings—Cloth and Leather A DICTIONARY MYTHOLOGYOF BEING A CONCISE GUIDE TO THE MYTHS OF GREECE AND ROME, BABYLONIA, EGYPT, AMERICA, SCANDINAVIA, & GREAT BRITAIN BY LEWIS SPENCE, M.A. Author of “ The Mythologies of Ancient Mexico and Peru,” etc. i CASSELL AND COMPANY, LTD. London, New York, Toronto and Melbourne 1910 ca') zz-^y . a k. WELLCOME INS77Tint \ LIBRARY Coll. W^iMOmeo Coll. No. _Zv_^ _ii ALL RIGHTS RESERVED INTRODUCTION Our grandfathers regarded the study of mythology as a necessary adjunct to a polite education, without a knowledge of which neither the classical nor the more modem poets could be read with understanding. But it is now recognised that upon mythology and folklore rests the basis of the new science of Comparative Religion. The evolution of religion from mythology has now been made plain. It is a law of evolution that, though the parent types which precede certain forms are doomed to perish, they yet bequeath to their descendants certain of their characteristics ; and although mythology has perished (in the civilised world, at least), it has left an indelible stamp not only upon modem religions, but also upon local and national custom. The work of Fruger, Lang, Immerwahr, and others has revolutionised mythology, and has evolved from the unexplained mass of tales of forty years ago a definite and systematic science.