Virtue Ethics and Education from Late Antiquity to the Eighteenth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I-Ii, Question 55, Article 4

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-16578-6 — Commentary on Thomas Aquinas's Virtue Ethics J. Budziszewski Excerpt More Information i-ii, question 55, article 4 Whether Virtue Is Suitably Dei ned? TEXT PARAPHRASE [1] Whether virtue is suitably dei ned? Is the traditional dei nition of virtue i tting? “Virtue is a good quality of the mind that enables us to live in an upright way and cannot be employed badly – one which God brings about in us, with- out us.” St. Thomas respectfully begins with this widely accepted dei nition because it would be arrogant to dismiss the result of generations of inquiry without examination. The ultimate source of the view which it encapsulates is St. Augustine of Hippo, but Augustine did not use precisely this wording. His more diffuse remarks had been condensed into a formula by Peter Lombard, 2 and the formula was then further sharpened by the Lombard’s disciples. Although St. Thomas begins with the tradition, he does not rest with it – he goes on to consider whether the received dei nition is actually correct. The i rst two Objections protest calling virtue a good quality. The third protests calling it a quality of the mind . The fourth objects to the phrase that it enables us to live rightly and the i fth to the phrase that it cannot be employed badly . Finally, the sixth protests the statement that God brings it about in us, without us . Although, in the end, St. Thomas accepts the dei nition, he does not accept it quite in the sense in which some of his predecessors did. -

Rosalind Hursthouse, on Virtue Ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999

Rosalind Hursthouse, On Virtue Ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999. Pp. x, 275. Reviewed by Gilbert Harman, Department of Philosophy, Princeton Univer- sity Virtue ethics is atype of ethicaltheory in which the notion of virtue or good character plays a central role. This splendid new book describes a “program” for the development of a particular (“Aristotelian”) form of virtue ethics. The book is intended to be used as a textbook, but should be read by anyone interested in moral philosophy. Hursthouse has been a major contributor to the development of virtue ethics and the program she describes, while making use of the many contributions of others, is very much her program, with numerous new ideas and insights. The book has three parts. The first dispels common misunderstandings and explains how virtue ethics applies to complex moral issues. The sec- ond discusses moral motivation, especially the motivation involved in doing something because it is right. The third explains how questions about the objectivity of ethics are to be approached within virtue ethics. Structure Hursthouse’s virtue ethics takes as central the conception of a human be- ing who possesses all ethical virtues of character and no vices or defects of character—”human being” rather than “person” because the relevant char- acter traits are “natural” to the species. To a first approximation, virtue ethics says that a right action is an action among those available that a perfectly virtuous human being would charac- teristically do under the circumstances. This is only a first approximation because of complications required in order accurately to describe certain moral dilemmas. -

CLARK PLANETARIUM SOLAR SYSTEM FACT SHEET Data Provided by NASA/JPL and Other Official Sources

CLARK PLANETARIUM SOLAR SYSTEM FACT SHEET Data provided by NASA/JPL and other official sources. This handout ©July 2013 by Clark Planetarium (www.clarkplanetarium.org). May be freely copied by professional educators for classroom use only. The known satellites of the Solar System shown here next to their planets with their sizes (mean diameter in km) in parenthesis. The planets and satellites (with diameters above 1,000 km) are depicted in relative size (with Earth = 0.500 inches) and are arranged in order by their distance from the planet, with the closest at the top. Distances from moon to planet are not listed. Mercury Jupiter Saturn Uranus Neptune Pluto • 1- Metis (44) • 26- Hermippe (4) • 54- Hegemone (3) • 1- S/2009 S1 (1) • 33- Erriapo (10) • 1- Cordelia (40.2) (Dwarf Planet) (no natural satellites) • 2- Adrastea (16) • 27- Praxidike (6.8) • 55- Aoede (4) • 2- Pan (26) • 34- Siarnaq (40) • 2- Ophelia (42.8) • Charon (1186) • 3- Bianca (51.4) Venus • 3- Amalthea (168) • 28- Thelxinoe (2) • 56- Kallichore (2) • 3- Daphnis (7) • 35- Skoll (6) • Nix (60?) • 4- Thebe (98) • 29- Helike (4) • 57- S/2003 J 23 (2) • 4- Atlas (32) • 36- Tarvos (15) • 4- Cressida (79.6) • Hydra (50?) • 5- Desdemona (64) • 30- Iocaste (5.2) • 58- S/2003 J 5 (4) • 5- Prometheus (100.2) • 37- Tarqeq (7) • Kerberos (13-34?) • 5- Io (3,643.2) • 6- Pandora (83.8) • 38- Greip (6) • 6- Juliet (93.6) • 1- Naiad (58) • 31- Ananke (28) • 59- Callirrhoe (7) • Styx (??) • 7- Epimetheus (119) • 39- Hyrrokkin (8) • 7- Portia (135.2) • 2- Thalassa (80) • 6- Europa (3,121.6) -

Greek Mythology

Greek Mythology The Creation Myth “First Chaos came into being, next wide bosomed Gaea(Earth), Tartarus and Eros (Love). From Chaos came forth Erebus and black Night. Of Night were born Aether and Day (whom she brought forth after intercourse with Erebus), and Doom, Fate, Death, sleep, Dreams; also, though she lay with none, the Hesperides and Blame and Woe and the Fates, and Nemesis to afflict mortal men, and Deceit, Friendship, Age and Strife, which also had gloomy offspring.”[11] “And Earth first bore starry Heaven (Uranus), equal to herself to cover her on every side and to be an ever-sure abiding place for the blessed gods. And earth brought forth, without intercourse of love, the Hills, haunts of the Nymphs and the fruitless sea with his raging swell.”[11] Heaven “gazing down fondly at her (Earth) from the mountains he showered fertile rain upon her secret clefts, and she bore grass flowers, and trees, with the beasts and birds proper to each. This same rain made the rivers flow and filled the hollow places with the water, so that lakes and seas came into being.”[12] The Titans and the Giants “Her (Earth) first children (with heaven) of Semi-human form were the hundred-handed giants Briareus, Gyges, and Cottus. Next appeared the three wild, one-eyed Cyclopes, builders of gigantic walls and master-smiths…..Their names were Brontes, Steropes, and Arges.”[12] Next came the “Titans: Oceanus, Hypenon, Iapetus, Themis, Memory (Mnemosyne), Phoebe also Tethys, and Cronus the wily—youngest and most terrible of her children.”[11] “Cronus hated his lusty sire Heaven (Uranus). -

Augustine's Ethics

15 BONNIE KENT Augustine’s ethics Augustine regards ethics as an enquiry into the Summum Bonum: the supreme good, which provides the happiness all human beings seek. In this respect his moral thought comes closer to the eudaimonistic virtue ethics of the classical Western tradition than to the ethics of duty and law associated with Christianity in the modern period. But even though Augustine addresses many of the same problems that pagan philosophers do, he often defends very different answers. For him, happiness consists in the enjoyment of God, a reward granted in the afterlife for virtue in this life. Virtue itself is a gift of God, and founded on love, not on the wisdom prized by philosophers. The art of living In Book 8 of De civitate Dei Augustine describes “moral philosophy” (a Latin expression), or “ethics” (the Greek equivalent), as an enquiry into the supreme good and how we can attain it. The supreme good is that which we seek for its own sake, not as a means to some other end, and which makes us happy. Augustine adds, as if this were an uncontroversial point, that happiness is the aim of philosophy in general.1 Book 19 opens with a similar discussion. In his summary of Varro’s treatise De philosophia, Augustine reports that no school of philosophy deserves to be considered a distinct school unless it differs from others on the supreme good. For the supreme good is that which makes us happy, and the only purpose of philosophizing is the attainment of happiness.2 Both of these discussions cast philosophy as a fundamentally practical discipline, so that ethics appears to overshadow logic, metaphysics, and other comparatively abstract areas as a philosopher’s chief concern. -

A Virtue Ethics Model Based on Care

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 The Virtuoso Human: A Virtue Ethics Model Based on Care Frederick Joseph Bennett University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons Scholar Commons Citation Bennett, Frederick Joseph, "The Virtuoso Human: A Virtue Ethics Model Based on Care" (2011). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3007 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Virtuoso Human: A Virtue Ethics Model Based on Care by Frederick J. Bennett A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Philosophy College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Thomas Williams, Ph.D. Joanne B. Waugh, Ph.D. Brook J. Sadler, Ph.D. Deni Elliott, Ed.D. Date of Approval: March 28, 2011 Keywords: Aristotle, Aquinas, Noddings, Charity, Unity © Copyright 2011, Frederick J. Bennett Table of Contents Abstract ii Chapter 1: Introduction 1 Chapter 2: Ethics 4 Virtue Ethics 7 Chapter 3: Aristotle’s Virtue 15 Borrowing from Aristotle 32 Modern Challenges to Virtue Ethics Theory from Aristotle’s Work 41 Aquinas and Aristotle 44 Chapter 4: Charity 48 Chapter 5: Care-Based Virtue Ethics Theory 56 The Problem 57 Hypothesis 59 First Principle 63 Care as a Foundation 64 The Virtue of Care 72 Care and Charity 78 Chapter 6: Framework for Care-Based Virtue Ethics 87 Care and the Virtues 87 The Good 89 The Virtuoso Human 91 Practical Wisdom 94 Chapter 7: Conclusion 97 References 101 i Abstract The goal of this thesis is to develop the foundation and structure for a virtue ethics theory grounded in a specific notion of care. -

Virtue Ethics As Moral Formation for Ignatian Education in Chile Juan Pablo Valenzuela

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons Jesuit School of Theology Dissertations Student Scholarship 5-2018 Virtue Ethics as Moral Formation for Ignatian Education in Chile Juan Pablo Valenzuela Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/jst_dissertations Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Valenzuela, Juan Pablo, "Virtue Ethics as Moral Formation for Ignatian Education in Chile" (2018). Jesuit School of Theology Dissertations. 32. https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/jst_dissertations/32 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jesuit School of Theology Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VIRTUE ETHICS AS MORAL FORMATION FOR IGNATIAN EDUCATION IN CHILE A thesis by Juan Pablo Valenzuela, S.J. presented to The Faculty of the Jesuit School of Theology of Santa Clara University in partial fulfillment for the requirements for the degree of Licentiate in Sacred Theology Berkeley, California May 2018 Committee Signatures _________________________________________ Lisa Fullam, Director May 9, 2018 _________________________________________ Eduardo Fernández, S.J. Reader May 9, 2018 Virtue Ethics as Moral Formation for Ignatian Education in Chile A thesis by Juan Pablo Valenzuela, S.J ABSTRACT The Catholic Church in Chile is in a state of moral perplexity. On one side, the hierarchy of the Church, moral theologians, and teachers propose and teach a morality based on rules and principles that does not take account of the context of the country and creates a distance from the moral perspective of the majority of the Chilean people. -

Doing the Right Thing: Business Ethics, Moral Indeterminancy & Existentialism

DOING THE RIGHT THING: BUSINESS ETHICS, MORAL INDETERMINANCY & EXISTENTIALISM Charles Sherwood London School of Economics Tutor: Susanne Burri Winner: Postgraduate Category Institute of Business Ethics Student Essay Competition 2017 Introduction Business ethics is a subject of growing interest to academics and practitioners alike. But can moral theory really guide business decision-making? And, can it do so when it matters? i.e. when those decisions get difficult. Difficult managerial decisions have many characteristics. They are important, often hurried, sometimes contentious. But, perhaps above all, they are ambiguous. We are unsure what is the right choice. Imagine the following… Arlette, an executive in a foreign-aid charity, needs to get vital supplies across a frontier to refugee families with children nearing starvation. Her agent on the ground is asked by border guards for a $5,000 bribe, some of which they will pocket personally and the rest of which will help fund a terror campaign. False, dishonest and illegal accounting will be required to disguise the use of the funds from donors and regulators. Arlette is coming up for promotion. She tries to explain the problem to her superior. He is impatient and just tells her to get the job done. Should Arlette allow the agent to pay the bribe? Moral theories struggle to resolve this kind of ambiguity, because they prove indeterminate in one of two ways: either they advocate a single, ‘monolithic’ principle that is all but impossible to apply in complex situations like the above; or they offer an array of principles that individually are more easily applied, yet conflict with each other. -

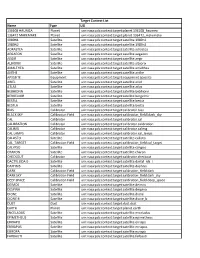

PDS4 Context List

Target Context List Name Type LID 136108 HAUMEA Planet urn:nasa:pds:context:target:planet.136108_haumea 136472 MAKEMAKE Planet urn:nasa:pds:context:target:planet.136472_makemake 1989N1 Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.1989n1 1989N2 Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.1989n2 ADRASTEA Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.adrastea AEGAEON Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.aegaeon AEGIR Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.aegir ALBIORIX Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.albiorix AMALTHEA Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.amalthea ANTHE Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.anthe APXSSITE Equipment urn:nasa:pds:context:target:equipment.apxssite ARIEL Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.ariel ATLAS Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.atlas BEBHIONN Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.bebhionn BERGELMIR Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.bergelmir BESTIA Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.bestia BESTLA Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.bestla BIAS Calibrator urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibrator.bias BLACK SKY Calibration Field urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibration_field.black_sky CAL Calibrator urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibrator.cal CALIBRATION Calibrator urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibrator.calibration CALIMG Calibrator urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibrator.calimg CAL LAMPS Calibrator urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibrator.cal_lamps CALLISTO Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.callisto -

A Dictionary of Mythology —

Ex-libris Ernest Rudge 22500629148 CASSELL’S POCKET REFERENCE LIBRARY A Dictionary of Mythology — Cassell’s Pocket Reference Library The first Six Volumes are : English Dictionary Poetical Quotations Proverbs and Maxims Dictionary of Mythology Gazetteer of the British Isles The Pocket Doctor Others are in active preparation In two Bindings—Cloth and Leather A DICTIONARY MYTHOLOGYOF BEING A CONCISE GUIDE TO THE MYTHS OF GREECE AND ROME, BABYLONIA, EGYPT, AMERICA, SCANDINAVIA, & GREAT BRITAIN BY LEWIS SPENCE, M.A. Author of “ The Mythologies of Ancient Mexico and Peru,” etc. i CASSELL AND COMPANY, LTD. London, New York, Toronto and Melbourne 1910 ca') zz-^y . a k. WELLCOME INS77Tint \ LIBRARY Coll. W^iMOmeo Coll. No. _Zv_^ _ii ALL RIGHTS RESERVED INTRODUCTION Our grandfathers regarded the study of mythology as a necessary adjunct to a polite education, without a knowledge of which neither the classical nor the more modem poets could be read with understanding. But it is now recognised that upon mythology and folklore rests the basis of the new science of Comparative Religion. The evolution of religion from mythology has now been made plain. It is a law of evolution that, though the parent types which precede certain forms are doomed to perish, they yet bequeath to their descendants certain of their characteristics ; and although mythology has perished (in the civilised world, at least), it has left an indelible stamp not only upon modem religions, but also upon local and national custom. The work of Fruger, Lang, Immerwahr, and others has revolutionised mythology, and has evolved from the unexplained mass of tales of forty years ago a definite and systematic science. -

Care Ethics and Virtue Ethics

Care Ethics and Virtue Ethics RAJA HALWANI The paper argues that care ethics should be subsumed under virtue ethics by constru- ing care as an important virtue. Doing so allows us to achieve two desirable goals. First, we preserve what is important about care ethics (for example, its insistence on particularity, partiality, emotional engagement, and the importance of care to our moral lives). Second, we avoid two important objections to care ethics, namely, that it neglects justice, and that it contains no mechanism by which care can be regulated so as not to be become morally corrupt. The issue of the status of care ethics (CE) as a moral theory is still unresolved. If, as has been argued, CE cannot, and should not, constitute a comprehen- sive moral theory, and if care cannot be the sole foundation of such a theory, the question of the status of CE becomes a pressing one, especially given the plausibility of the idea that caring does constitute an important and essential component of moral thinking, attitude, and behavior. Furthermore, the answers given to solve this issue are inadequate. For instance, the suggestion that CE has its own moral domain to operate in (for example, friendship), while, say, an ethics of justice has another (public policy), seems to encounter difficulties when we realize that in the former domain justice is required. I want to suggest that CE be part of a more comprehensive moral framework, namely, virtue ethics (VE). Doing so allows us to achieve two general, desir- able goals. First, by incorporating care within VE, we will be able to imbed CE within a comprehensive moral theory and so accommodate the criticism that such an ethics cannot stand on its own. -

Studies on the Genus Munida Leach, 1820 (Galatheidae) in New Caledonian and Adjacent Waters with Descriptions of 56 New Species

RESULTATS DES CAMPAGNES MUSORSTOM, VOLUME 12 — RESULTATS DES CAMPAGNES MUSORSTOM, VOLUME 12 — RESULTATS DEJ 12 Crustacea Decapoda : Studies on the genus Munida Leach, 1820 (Galatheidae) in New Caledonian and adjacent waters with descriptions of 56 new species Enrique MACPHERSON Instituto de Ciencias del Mar. CS1C Paseo Joan de BorbcS s/n 08039 Barcelona. Spain ABSTRACT A large collection of species of the genus Munida has been examined and found to contain 56 undescribed species. The specimens examined were caught mainly off New Caledonia, Chesterfield Islands, Loyalty Islands, Matthew and Hunter Islands. Several samples from Kiribati, the Philippines and Indonesia have also been included. The specimens were collected between 6 and 2 049 m. Some species previously known in the area (Af. gracilis, M. haswelli, M. microps, M. spinicordata and M. tubercidata) have been illustrated. These results point up the high diversity of this genus in the region and the importance of several characters in species identification (e.g., size and number of lateral spines on the carapace, ornamentation of the thoracic sternites, size of antennular and antennal spines, colour pattern). RESUME Crustacea Decapoda : Le genre Munida Leach, 1820 (Galatheidae) dans les eaux neo-ca!6doniennes et avoisinantes. Description de 56 especes nouvelles. Une collection comprenant 76 especes du genre Munida dont 56 sont nouvelles, r£colt£e principalement autour de la Nouvelle-Cal&lonie, les Ties Chesterfield, Loyaute, Matthew et Hunter, entre 6 et 2049 m de profondeur, est etudiee ici. Outre les especes nouvelles, on a illustre quelques especes deja connues de la region : M. gracilis, M, haswelli, M.