Will Eno: the Page, the Stage, and the Word This Thesis Examines the Works of Playwright Will Eno

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crave Theatre Company Presents

Crave Theatre Company Presents Starring……………………………………………………………...…….Todd Van Voris* Director………………………………………………………………………Sarah Andrews Stage Manager…………………………………………………..….. Kylie Jenifer Rose Set Designer………………………………………………………………………..Max Ward Light Designer……………………………………………………………….. Phil Johnson Sound Designer ……………………………………………………………..Austin Raver “THOM PAIN (based on nothing)” was first presented at the Pleasance Courtyard, Edinburgh by Soho Theatre Company in association with Chantal Arts + Theatre and Naked Angels (NYC) on August 5th 2004, before transforming into Soho Theatre, London on September 3. On its transfer to DR2 Theatre, New York, on February 1, 2005, “THOM PAIN (based on nothing)” was produced by Robert Boyett and Daryl Roth. “THOM PAIN (BASED ON NOTHING)” is presented by special arrangement with Dramatist Play Services, Inc., New York. Special thanks to: Matt Smith, Andrew Bray, The Steep and Thorny Way to Heaven, Russell J. Young, defunkt theatre, Imago Theatre, Theatre Vertigo, Joyce Robbs, Paul Angelo, Joel Patrick Durham, Joe Jatcko and Jen Mitas. *The Actor appears through the courtesy of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. Director’s Notes: Picture, if you will, a man sitting, sometimes standing under a tree next to a cart. Long beard, expanded stomach, covered in the filth of the month and the clothes he wore yesterday. The cart filled with garbage that he deemed important. He stands there day and night, with no home to go to other than the tree, which provides him coverage from rain. Sometimes he can be seen smoking, sometimes he’s drinking a beer, and he always looks like he doesn’t want anything to do with you, until you say “hi.” His name was Don. -

Casting Announced for the Uk Premiere of the Realistic Joneses

PRESS RELEASE - Monday 16 December 2019 IMAGES CAN BE DOWNLOADED here Twitter/ Facebook / website CASTING ANNOUNCED FOR THE UK PREMIERE OF THE REALISTIC JONESES ▪ WILL ENO’S AWARD-WINNING THE REALISTIC JONESES, CITED IN NUMEROUS BEST PLAY LISTS FOLLOWING ITS BROADWAY PREMIERE, WILL BE STAGED AT THEATRE ROYAL BATH’S USTINOV STUDIO FOR SPRING 2020 ▪ FULL CAST INCLUDES COREY JOHNSON, SHARON SMALL, JACK LASKEY AND CLARE FOSTER ▪ THE REALISTIC JONESES WILL RUN FROM 6 FEBRUARY TO 7 MARCH 2020 AND IS DIRECTED BY SIMON EVANS Theatre Royal Bath Productions has today announced casting for the UK premiere of Will Eno’s Drama Desk Award winning play The Realistic Joneses which will be staged in the Ustinov Studio from Thursday 6 February to Saturday 7 March 2020 with opening night for press on Wednesday 12 February 2020. The full cast includes Corey Johnson as Bob, Sharon Small as Jennifer, Jack Laskey as John and Clare Foster as Pony. The production is directed by Simon Evans. The Realistic Joneses is a hilarious, quirky and touching portrait of marriage, life and squirrels, by American playwright Will Eno. Seen on Broadway in 2014, the play received a Drama Desk Special Award, was named one of the ‘25 best American plays since Angels in America’ by the New York Times, Best Play on Broadway by USA Today and best American play of 2014 by the Guardian. In a suburban backyard, one bucolic evening, Bob and Jennifer Jones and their new neighbours John and Pony Jones find they have more in common than their identical homes and last name. -

The Journal of the Dramatists Guild of America, Inc

The Journal of the Dramatists Guild of America, Inc. The the ageissue 2016 NOV/DEC $7 USD €10 EUR www.dramatistsguild.com FrontCOVER.indd 1 10/5/16 12:57 PM To enroll, go to http://www.dginstitute.org SEP/OCTJul/Aug DGI 16 ad.indd FrontCOVERs.indd 1 2 5/23/168/8/16 1:341:52 PM VOL. 19 No 2 TABLE OF NOV/DEC 2016 2 Editor’s Notes CONTENTS 3 Dear Dramatist 4 News 7 Inspiration – KIRSTEN CHILDS 8 The Craft – KAREN HARTMAN 10 Edward Albee 1928-2016 13 “Emerging” After 50 with NANCY GALL-CLAYTON, JOSH GERSHICK, BRUCE OLAV SOLHEIM, and TSEHAYE GERALYN HEBERT, moderated by AMY CRIDER. Sidebars by ANTHONY E. GALLO, PATRICIA WILMOT CHRISTGAU, and SHELDON FRIEDMAN 20 Kander and Pierce by MARC ACITO 28 Profile: Gary Garrison with CHISA HUTCHINSON, CHRISTINE TOY JOHNSON, and LARRY DEAN HARRIS 34 Writing for Young(er) Audiences with MICHAEL BOBBITT, LYDIA DIAMOND, ZINA GOLDRICH, and SARAH HAMMOND, moderated by ADAM GWON 40 A Primer on Literary Executors – Part One by ELLEN F. BROWN 44 James Houghton: A Tribute with JOHN GUARE, ADRIENNE KENNEDY, WILL ENO, NAOMI WALLACE, DAVID HENRY HWANG, The REGINA TAYLOR, and TONY KUSHNER Dramatistis the official journal of Dramatists Guild of America, the professional organization of 48 DG Fellows: RACHEL GRIFFIN, SYLVIA KHOURY playwrights, composers, lyricists and librettists. 54 National Reports It is the only 67 From the Desk of Dramatists Guild Fund by CHISA HUTCHINSON national magazine 68 From the Desk of Business Affairs by AMY VONVETT devoted to the business and craft 70 Dramatists Diary of writing for 75 New Members theatre. -

Downloaded by Michael Mitnick and Grace, Or the Art of Climbing by Lauren Feldman

The Dream Continues: American New Play Development in the Twenty-First Century by Gregory Stuart Thorson B.A., University of Oregon, 2001 M.A., University of Colorado, 2008 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Theatre This thesis entitled: The Dream Continues: American New Play Development in the Twenty-First Century written by Gregory Stuart Thorson has been approved by the Department of Theatre and Dance _____________________________________ Dr. Oliver Gerland ____________________________________ Dr. James Symons Date ____________ The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. IRB protocol # 12-0485 iii Abstract Thorson, Gregory Stuart (Ph.D. Department of Theatre) The Dream Continues: American New Play Development in the Twenty-First Century Thesis directed by Associate Professor Oliver Gerland New play development is an important component of contemporary American theatre. In this dissertation, I examined current models of new play development in the United States. Looking at Lincoln Center Theater and Signature Theatre, I considered major non-profit theatres that seek to create life-long connections to legendary playwrights. I studied new play development at a major regional theatre, Denver Center Theatre Company, and showed how the use of commissions contribute to its new play development program, the Colorado New Play Summit. I also examined a new model of play development that has arisen in recent years—the use of small black box theatres housed in large non-profit theatre institutions. -

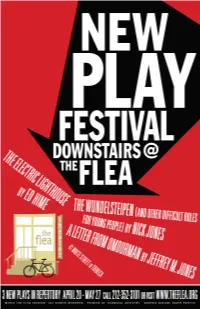

The Flea Theater

THE FLEA THEATER JIM SIMP S ON ARTISTIC DIRECTOR CAROL OS TROW PRODUCING DIRECTOR BETH DEM B ROW MANAGING DIRECTOR PRESENTS THE WORLD PREMIERE OF A LETTER FROM OMDURMAN WRITTEN BY JEFFREY M. JONE S DIRECTED BY PAGE BURKHOL D ER FEATURING HE AT S T B KATE SIN C LAIR FO S TER SET DESIGN JONATHAN COTTLE LIGHTING DESIGN WHITNEY LO C HER COSTUME DESIGN COLIN WHITELY SOUND DESIGN DAN DURKIN PROJECTION DESIGN JULON D RE BROWN STAGE MANAGMENT A LETTER FROM OMDURMAN CAST (IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE ) Dave...............................................................................................................Matt Barbot Charlie..........................................................................................................Wilton Yeung Wyatt................................................................................................................Will Turner Josie........................................................................................................Veracity Butcher Understudies: Eric Folks (Wyatt), Danny Rivera (Charlie & Dave) CREATIVE TEAM Playwright.............................................................................................................Jeffrey M. Jones Director................................................................................................................Page Burkholder Set Design......................................................................................................Kate Sinclair Foster Lighting Design......................................................................................................Jonathan -

Thom Pain Broadwayhd Release FINAL

Contact: DKC Public Relations Emily McGill 212.981.5128 BROADWAYHD TO STREAM RAINN WILSON IN SOLO PERFORMANCE OF WILL ENO'S THOM PAIN (BASED ON NOTHING) OLIVER BUTLER AND WILL ENO DIRECT FILM ADAPTATION OF GEFFEN PLAYHOUSE PRODUCTION OF THE PULITZER PRIZE FINALIST PLAY New York, November 1, 2017 – BroadwayHD announces today that Thom Pain, the Geffen Playhouse’s filmed adaptation of its stage production of Will Eno’s lauded play Thom Pain (based on nothing) starring Rainn Wilson (“The Office,” founder of Soul Pancake), will be available on BroadwayHD beginning January 11, 2018. The play was a finalist for the 2005 Pulitzer Prize in Drama and has been translated into more than fifteen languages, with more than 100 productions mounted worldwide. Thom Pain, the film, will open the Indie Memphis Film Festival today and will also screen as part of the Dallas VideoFest this weekend. Of the play, Charles Isherwood in his review in The New York Times wrote: “It’s one of those treasured nights in the theater – treasured nights anywhere, for that matter – that can leave you both breathless with exhilaration and, depending on your sensitivity to meditations on the bleak and beautiful mysteries of human experience, in a puddle of tears. Also in stitches, here and there.” First performed to rave reviews in 2004 at the Edinburgh Festival where it won every major honor including a First Fringe Award, Thom Pain (based on nothing) next moved to the Soho Theatre in London and then on to the DR2 Theatre in New York, where it ran for more than 350 performances. -

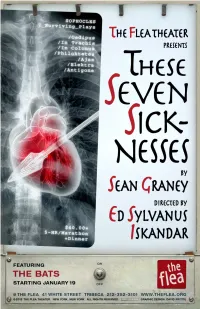

These-Seven-Sicknesses.Pdf

THE FLEA THEATER JIM SIMP S ON ARTISTIC DIRECTOR CAROL OS TROW PRODUCING DIRECTOR BETH DEM B ROW MANAGING DIRECTOR PRESENTS THE NEW YORK PREMIERE OF THESE SEVEN SICKNESSES WRITTEN BY SEAN GRANEY DIRECTED BY ED SYLVANU S IS KAN D AR FEATURING THE BAT S JULIA NOULIN -MERAT SET DESIGN CARL WIEMANN LIGHTING DESIGN LOREN SHAW COSTUME DESIGN PATRI C K METZ G ER SOUND DESIGN MI C HAEL WIE S ER FIGHT DIRECTION DAVI D DA bb ON MUSIC DIRECTION GRE G VANHORN DRAMATURG ED WAR D HERMAN , KARA KAUFMAN STAGE MANAGMENT These Seven Sicknesses was originally incubated in New York City during Lab 2 at Exit, Pursued by a Bear (EPBB), March 2011; Ed Sylvanus Iskandar, Artistic Director. THESE SEVEN SICKNESSES CAST (IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE ) PROLOGUE Orderly..............................................................................................................Will Turner Nurse 1.........................................................................................................Glenna Grant New Nurse .........................................................................................Tiffany Abercrombie Nurse 2........................................................................................................Eloise Eonnet Nurse 3.............................................................................................Marie Claire Roussel Nurse 4...........................................................................................................Jenelle Chu Nurse 5.........................................................................................................Olivia -

Title and Deed/Oh, the Humanity and Other Good Intentions by Will Eno

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Dafina McMillan November 13, 2014 [email protected] | 212-609-5955 Gus Schulenburg [email protected] | 212-609-5941 New from TCG Books: Title and Deed/Oh, the Humanity and Other Good Intentions by Will Eno NEW YORK, NY – Theatre Communications Group (TCG) is pleased to announce the publication of Will Eno’s Title and Deed/Oh, the Humanity and Other Good Intentions. Title and Deed originally premiered in Ireland in 2011 before its first American production in 2012 at Signature Theatre Company in New York. Oh, the Humanity and Other Good Intentions, a collection of five short plays, premiered at the Flea Theater in New York in 2007, and enjoyed a successful run at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival in 2012. "A haunting and often fiercely funny meditation... The marvel of Mr. Eno’s voice is how naturally it combines a carefully sculptured lyricism with sly, poker-faced humor. Everyday phrases and familiar platitudes – ‘Don’t ever change,’ ‘Who knows’ – are turned inside out or twisted into blunt, unexpected punch lines punctuating long rhapsodic passages that leave you happily word-drunk." — Charles Isherwood, New York Times on Title and Deed Known for his wry humor and deeply moving plays, Will Eno’s “gift for articulating life’s absurd beauty and its no less absurd horrors may be unmatched among writers of his generation” (New York Times). This new volume of the acclaimed playwright’s work includes five short plays about being alive – Behold the Coach, in a Blazer, Uninsured; Ladies and Gentlemen, the Rain; Enter the Spokeswoman, Gently; The Bully Composition; and Oh, the Humanity – as well as Title and Deed, a chilling and severely funny solo rumination on life as everlasting exile. -

School of Drama 2015–2016

BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY BULLETIN OF YALE BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Periodicals postage paid New Haven ct 06520-8227 New Haven, Connecticut School of Drama 2015–2016 School of Drama 2015–2016 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 111 Number 13 August 30, 2015 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 111 Number 13 August 30, 2015 (USPS 078-500) The University is committed to basing judgments concerning the admission, education, is published seventeen times a year (one time in May and October; three times in June and employment of individuals upon their qualifications and abilities and a∞rmatively and September; four times in July; five times in August) by Yale University, 2 Whitney seeks to attract to its faculty, sta≠, and student body qualified persons of diverse back- Avenue, New Haven CT 0651o. Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut. grounds. In accordance with this policy and as delineated by federal and Connecticut law, Yale does not discriminate in admissions, educational programs, or employment against Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, any individual on account of that individual’s sex, race, color, religion, age, disability, PO Box 208227, New Haven CT 06520-8227 status as a protected veteran, or national or ethnic origin; nor does Yale discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity or expression. Managing Editor: Kimberly M. Go≠-Crews University policy is committed to a∞rmative action under law in employment of Editor: Lesley K. Baier women, minority group members, individuals with disabilities, and protected veterans. PO Box 208230, New Haven CT 06520-8230 Inquiries concerning these policies may be referred to Valarie Stanley, Director of the O∞ce for Equal Opportunity Programs, 221 Whitney Avenue, 3rd Floor, 203.432.0849. -

Rainn Wilson in Solo Performance of Will Eno's Thom Pain (Based on Nothing) Oliver Butler to Helm the Pulitzer Prize Finalist Play

MEDIA CONTACT: Katy Sweet & Associates [email protected]/310-479-2333 RAINN WILSON IN SOLO PERFORMANCE OF WILL ENO'S THOM PAIN (BASED ON NOTHING) OLIVER BUTLER TO HELM THE PULITZER PRIZE FINALIST PLAY JANUARY 8 TO FEBRUARY 14, 2016 (OPENING NIGHT IS JANUARY 13) IN THE AUDREY SKIRBALL KENIS THEATER AT THE GEFFEN PLAYHOUSE LOS ANGELES (November 18, 2015) Geffen Playhouse announces a premiere theatrical event for Los Angeles – ten years in the making. Will Eno’s lauded play was a finalist for the 2005 Pulitzer Prize in Drama and has been translated into more than fifteen languages, with more than 100 productions mounted worldwide. Multi-faceted, award-winning actor, Rainn Wilson (The Office, founder of Soul Pancake) and playwright Will Eno became friends more than 20 years ago, well before the play’s critically acclaimed world premiere. Eager to bring Thom Pain to Los Angeles, the two had spoken about working together for years. It was only recently that all the stars aligned. The Geffen Playhouse run will be a limited engagement and part of the not-for-profit's Spotlight Entertainment Series which brought a similarly anticipated play (I'll Eat You Last featuring Bette Midler) to Los Angeles two years ago. Charles Isherwood in his review in The New York Times wrote: “It’s one of those treasured nights in the theater – treasured nights anywhere, for that matter – that can leave you both breathless with exhilaration and, depending on your sensitivity to meditations on the bleak and beautiful mysteries of human experience, in a puddle of tears. -

One Night Stand

ONE NIGHT STAND FIND HIM Written & Performed by DYLAN GUERRA Directed by LAURA DUPPER FIND HIM EPISODE 1 • NOVEMBER 9 EPISODE 2 • NOVEMBER 19 EPISODE 3 • DECEMBER 7 EPISODE 4 • DECEMBER 17 THE TEAM Written & Performed by DYLAN GUERRA Directed by LAURA DUPPER Cinematography HOLLY SETTOON Original Music CHARLES HUMENRY Editor RICARDO DÁVILA THE ARTISTS WOULD LIKE TO THANK Ars Nova, Kristen Kelso, Dagny Stewart, Dalton Fowler, Ryan Avalos, Jacob Conway and Stephanie Machado. Ars Nova operates on the unceded land of the Lenape peoples on the island of Manhahtaan (Mannahatta) in Lenapehoking, the Lenape Homeland. We acknowledge the brutal history of this stolen land and the displacement and dispossession of its Indigenous people. We also acknowledge that after there were stolen lands, there were stolen people. We honor the generations of displaced and enslaved people that built, and continue to build, the country that we occupy today. We gathered together in virtual space to watch this performance. We encourage you to consider the legacies of colonization embedded within the technology and structures we use and to acknowledge its disproportionate impact on communities of color and Indigenous peoples worldwide. We invite you to join us in acknowledging all of this as well as our shared responsibility: to consider our way forward in reconciliation, decolonization, anti-racism and allyship. We commit ourselves to the daily practice of pursuing this work. ABOUT THE ARTISTS DYLAN GUERRA (Writer/Performer) is a gay Latinx New York City-based artist originally from Miami, Florida. His work has been seen at Ars Nova, Dixon Place, HERE and other places around the city. -

SARAH RUHL and TRACY LETTS Two Playwrights and Three Sisters

conversations SaRAH RUhL and TRaCy LeTTS Two playwrights and Three Sisters Moderated by and Rob Weinert-KendT L Sarah Ruhl and Tracy Letts meet in Manhattan to talk Chekhov. ande why arah RuHl and Tracy Letts are two of Rob weinert-kendT: I understand that in both your the most frequently produced playwrights in the U.S., and cases, you were assigned translations you didn’t love, and both have strong Chicago roots: he as an eager transplant from then found other collaborators. Oklahoma, she as a native of the suburb Wilmette. Tracy Letts: When Artists Rep first asked me to do this, they There the similarities between Letts and Ruhl would supplied me with a literal translation from what appeared to seem to end. She has made her name with a wildly eclectic be an old textbook called Hugo’s Russian Reading Simplified. My S series of plays that have in common a vivid lyricism, leavened first pass through the script was using that translation. It was by magic-realist flights of fancy The( Clean House; Dead Man’s like math; it was some of the hardest stuff I’ve ever done, just Cell Phone; In the Next Room, or the vibrator play). Letts, on the trying to figure out what the sentences were. I got to the end other hand, penned the ferocious Killer Joe and Bug before of it and I realized that some of the things I’d done just made constructing the monumental Pulitzer winner August: Osage no sense; some things were exactly wrong. County for the actors of Steppenwolf Theatre Company, where I was in London at the time doing August at the National, he has been an ensemble member since 2002.