The Morning Line

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RHYTHM & BLUES...63 Order Terms

5 COUNTRY .......................6 BEAT, 60s/70s ..................71 AMERICANA/ROOTS/ALT. .............22 SURF .............................83 OUTLAWS/SINGER-SONGWRITER .......23 REVIVAL/NEO ROCKABILLY ............85 WESTERN..........................27 PSYCHOBILLY ......................89 WESTERN SWING....................30 BRITISH R&R ........................90 TRUCKS & TRAINS ...................30 SKIFFLE ...........................94 C&W SOUNDTRACKS.................31 AUSTRALIAN R&R ....................95 C&W SPECIAL COLLECTIONS...........31 INSTRUMENTAL R&R/BEAT .............96 COUNTRY AUSTRALIA/NEW ZEALAND....31 COUNTRY DEUTSCHLAND/EUROPE......32 POP.............................103 COUNTRY CHRISTMAS................33 POP INSTRUMENTAL .................136 BLUEGRASS ........................33 LATIN ............................148 NEWGRASS ........................35 JAZZ .............................150 INSTRUMENTAL .....................36 SOUNDTRACKS .....................157 OLDTIME ..........................37 EISENBAHNROMANTIK ...............161 HAWAII ...........................38 CAJUN/ZYDECO ....................39 DEUTSCHE OLDIES ..............162 TEX-MEX ..........................39 KLEINKUNST / KABARETT ..............167 FOLK .............................39 Deutschland - Special Interest ..........167 WORLD ...........................41 BOOKS .........................168 ROCK & ROLL ...................43 BOOKS ...........................168 REGIONAL R&R .....................56 DISCOGRAPHIES ....................174 LABEL R&R -

Crave Theatre Company Presents

Crave Theatre Company Presents Starring……………………………………………………………...…….Todd Van Voris* Director………………………………………………………………………Sarah Andrews Stage Manager…………………………………………………..….. Kylie Jenifer Rose Set Designer………………………………………………………………………..Max Ward Light Designer……………………………………………………………….. Phil Johnson Sound Designer ……………………………………………………………..Austin Raver “THOM PAIN (based on nothing)” was first presented at the Pleasance Courtyard, Edinburgh by Soho Theatre Company in association with Chantal Arts + Theatre and Naked Angels (NYC) on August 5th 2004, before transforming into Soho Theatre, London on September 3. On its transfer to DR2 Theatre, New York, on February 1, 2005, “THOM PAIN (based on nothing)” was produced by Robert Boyett and Daryl Roth. “THOM PAIN (BASED ON NOTHING)” is presented by special arrangement with Dramatist Play Services, Inc., New York. Special thanks to: Matt Smith, Andrew Bray, The Steep and Thorny Way to Heaven, Russell J. Young, defunkt theatre, Imago Theatre, Theatre Vertigo, Joyce Robbs, Paul Angelo, Joel Patrick Durham, Joe Jatcko and Jen Mitas. *The Actor appears through the courtesy of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. Director’s Notes: Picture, if you will, a man sitting, sometimes standing under a tree next to a cart. Long beard, expanded stomach, covered in the filth of the month and the clothes he wore yesterday. The cart filled with garbage that he deemed important. He stands there day and night, with no home to go to other than the tree, which provides him coverage from rain. Sometimes he can be seen smoking, sometimes he’s drinking a beer, and he always looks like he doesn’t want anything to do with you, until you say “hi.” His name was Don. -

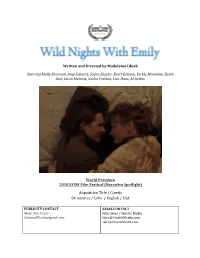

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek Starring Molly Shannon, Amy Seimetz, Susan Ziegler, Brett Gelman, Jackie Monahan, Kevin Seal, Dana Melanie, Sasha Frolova, Lisa Haas, Al Sutton World Premiere 2018 SXSW Film Festival (Narrative Spotlight) Acquisition Title / Cinetic 84 minutes / Color / English / USA PUBLICITY CONTACT SALES CONTACT Mary Ann Curto John Sloss / Cinetic Media [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE FILM PRESS MATERIALS CONTACT and FILM CONTACT: Email: [email protected] DOWNLOAD FILM STILLS ON DROPBOX/GOOGLE DRIVE: For hi-res press stills, contact [email protected] and you will be added to the Dropbox/Google folder. Put “Wild Nights with Emily Still Request” in the subject line. The OFFICIAL WEBSITE: http://wildnightswithemily.com/ For news and updates, click 'LIKE' on our FACEBOOK page: https://www.facebook.com/wildnightswithemily/ "Hilarious...an undeniably compelling romance. " —INDIEWIRE "As entertaining and thought-provoking as Dickinson’s poetry.” —THE AUSTIN CHRONICLE SYNOPSIS THE STORY SHORT SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in " Wild Nights With Emily," a dramatic comedy. The film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman. LONG SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in the dramatic comedy " Wild Nights with Emily." The poet’s persona, popularized since her death, became that of a reclusive spinster – a delicate wallflower, too sensitive for this world. This film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman (Susan Ziegler). After Emily died, a rivalry emerged when her brother's mistress (Amy Seimetz) along with editor T.W. -

George B. Seitz Motion Picture Stills, 1919-Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8h41trq No online items Finding Aid for the George B. Seitz motion picture stills, 1919-ca. 1944 Processed by Arts Special Collections Staff, pre-1999; machine-readable finding aid created by Julie Graham and Caroline Cubé; supplemental EAD encoding by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] ©2014 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the George B. PASC 31 1 Seitz motion picture stills, 1919-ca. 1944 Title: George B. Seitz motion picture stills Collection number: PASC 31 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 3.8 linear ft.(9 boxes) Date (bulk): Bulk, 1930-1939 Date (inclusive): ca. 1920-ca. 1942, ca. 1930s Abstract: George B. Seitz was an actor, screenwriter, and director. The collection consists of black and white motion picture stills representing 30-plus productions related to Seitz's career. Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Creator: Seitz, George B., 1888-1944 Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to UCLA Library Special Collections. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. -

Marina Draghici | Costume Designer

marina draghici costume designer film television rage – director; sally potter, producers; andrew fierberg, christopher sheppard adventure pictures | vox 3 films cast; jude law, john leguizamo, steve buscemi, judi dench, diane wiest, lily cole, adriana barraza *2009 berlin film festival* push – director; lee daniels, producer; lee daniels | smokewood entertainment cast; gabourey sidibe, mo’nique, paula patton, lenny kravitz, sherri sheperd, mariah carey *winner grand jury prize, audience award and special jury prize for acting - 2009 sundance film festival* the cake eaters (in post-production) - director; mary stuart masterson, producers; allen bain, darren goldberg, mary stuart masterson, elisa pugliese | 57th & irving productions | the 7th floor cast; kristen stewart, aaron stanford, bruce dern, elisabeth ashley, jayce bartok * 2007 tribeca film festival * standard operating procedure - director; errol morris | sony pictures classics cast; joshua feinman, merry grissom, cyrus king babylon fields (pilot) - director; michael cuesta, producers michael cuesta, margo myers | fox televisioncbs cast; roy stevenson, amber tamblyn, jamie sheridan, kathy baker, will janowitz the night listener - director; patrick stettner | hart|sharp entertainment | miramax films cast; robin williams, toni collette, sandra oh, bobby cannavale, rory culkin dexter (pilot) - director; michael cuesta, producers john goldwyn, sara colleton, michael cuesta | showtime cast; michael c. hall, jennifer carpenter, james remar heights - director; chris terrio | merchant -

Casting Announced for the Uk Premiere of the Realistic Joneses

PRESS RELEASE - Monday 16 December 2019 IMAGES CAN BE DOWNLOADED here Twitter/ Facebook / website CASTING ANNOUNCED FOR THE UK PREMIERE OF THE REALISTIC JONESES ▪ WILL ENO’S AWARD-WINNING THE REALISTIC JONESES, CITED IN NUMEROUS BEST PLAY LISTS FOLLOWING ITS BROADWAY PREMIERE, WILL BE STAGED AT THEATRE ROYAL BATH’S USTINOV STUDIO FOR SPRING 2020 ▪ FULL CAST INCLUDES COREY JOHNSON, SHARON SMALL, JACK LASKEY AND CLARE FOSTER ▪ THE REALISTIC JONESES WILL RUN FROM 6 FEBRUARY TO 7 MARCH 2020 AND IS DIRECTED BY SIMON EVANS Theatre Royal Bath Productions has today announced casting for the UK premiere of Will Eno’s Drama Desk Award winning play The Realistic Joneses which will be staged in the Ustinov Studio from Thursday 6 February to Saturday 7 March 2020 with opening night for press on Wednesday 12 February 2020. The full cast includes Corey Johnson as Bob, Sharon Small as Jennifer, Jack Laskey as John and Clare Foster as Pony. The production is directed by Simon Evans. The Realistic Joneses is a hilarious, quirky and touching portrait of marriage, life and squirrels, by American playwright Will Eno. Seen on Broadway in 2014, the play received a Drama Desk Special Award, was named one of the ‘25 best American plays since Angels in America’ by the New York Times, Best Play on Broadway by USA Today and best American play of 2014 by the Guardian. In a suburban backyard, one bucolic evening, Bob and Jennifer Jones and their new neighbours John and Pony Jones find they have more in common than their identical homes and last name. -

Elevating Voices Across Stage and Screen

Elevating voices across stage and screen clients include beginners, aspiring singers Based in London, Fiona continued to coach and performing arts students as well as singers and, in 2010, started working for top-tier professionals. Passionate about Andrew Lloyd Webber and his production vocal health and technique, Fiona believes company, the Really Useful Group. She that anyone can sing and tailors each worked on her first major international lesson to the client’s needs. She works production in 2012, as the vocal coach on remotely via Skype and in person from her Lloyd Webber’s Jesus Christ Superstar, studio at the London Palladium. and has since worked on dozens of major shows across television, film and theatre Fiona grew up on a farm outside around the world. Edinburgh where she immersed herself in music from a young age, initially training Fiona is always at the leading edge of in dance. In 2006, she left Scotland to vocal education. She travels globally to FIONA study Music at the Paul McCartney conferences that are advancing the field Liverpool Institute for Performing Arts, of vocal science and is supported by MCDOUGAL where her vocal coach inspired her to a network of exceptional ENT doctors, study voice education alongside her speech and language therapists, and degree. When she graduated with a first physiotherapists. She is considered a Fiona has worked with some of the biggest class honours degree in 2010, she already valuable link between singers and industry names in the entertainment industry, from had three years of coaching experience. representatives and consults for record Glenn Close to Taylor Swift, Judi Dench to She was the lead singer in a pop duo labels, agents, managers, performing Jennifer Hudson – but her busy studio also called Untouched (along with songwriting arts colleges, choreographers, directors, embraces people who sing for pleasure partner David Wilson), which later signed songwriters, film studios, musicians and and want to improve their voice. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

(Dayton, Ohio), 1940-09-27

FRIDAY. SEPTEMBER 27, 1940. ' THE FORUM PAGE SEVEN RIDGEW00D STALWART DILLARD LINESMAN >* *2 HEIGHTS n "Vv V'I :— " • ^ *-,v .x (CROWN POINT) Send all news t0 be published to Mrs. Prilly Wright, Tuesday of each WPckj 274 Cornell uvonue phone ADams 5395. Miss Lula Wright, daughter of • tu c Mr*. Prilly Wright of 274 Cornell avenue is very much improv v . atcer a severe illnc j. .Among ^oine of the early squirrel 1 tenters W£ts Mr. Prilly Wri.-rht wh. was seen coming in Wednesday nig!i with his license on his back but w i r<0 squirrels. trtl Mr. and Mrs. Irvin Orr and Mr. ar.d Mrs. Vermont Dickerson of iivinpver street were the house guests of Mr. and Mrs. Smith and Mrs. ijm Gaston of Chicago. vWhile there dominant! they visited the Negro Exposition and the Catholic church exposition. They saw the Streets of Paris and th,e Joe Louis exhibits and other in teresting sights. • • * Dtaglus Community Club li The Douglass Community Club has ordered 100 chairs for the center. All members are urged to be pres ent Monday October 6, business of :4k importance. Come and see the show ELLIOTT GRAY^ I every Tuesday night. The WPA Elliott Gray, stalwart Dillard ;ftis Gra Is expecten to give a band will P*ay at the center every y linesman, wh0 with Peter Tliornlou, Wednesday night, you will enjoy good account of himself in his final J will captain the Dillard Blue Devils thei music. r » this season. A veteran of three sea- year. He hails from St. -

SLEMCO Power September-October 2011

SEPT/OCT 2 0 1 1 SLEMCOPOWER HAUNTED HOUSES Three Acadiana ghost stories T’Frere’s Bed & Breakfast PAGE 4 SHARE STORIES FROM SLEMCO’S HISTORY PAGE 2 WEATHER EMERGENCIES PAGE 3 HADACOL PAGE 7 PSLEMCO OWER TakeNote Volume 61 No. 5 September/October 2011 The Official Publication of the Southwest Louisiana Electric Membership Corporation 3420 NE Evangeline Thruway P.O. Box 90866 Lafayette, Louisiana 70509 Phone 337-896-5384 www.slemco.com BOARD OF DIRECTORS ACADIA PARISH Merlin Young Bryan G. Leonards, Sr., Secretary ST. MARTIN PARISH William Huval, First Vice President Adelle Kennison LAFAYETTE PARISH Dave Aymond, Treasurer Jerry Meaux, President TELL US YOUR STORIES ABOUT ST. LANDRY PARISH H. F. Young, Jr. Leopold Frilot, Sr. SLEMCO’S EARLY YEARS VERMILION PARISH Joseph David Simon, Jr., LEMCO will celebrate its 75th anni- electric cooperatives. But our history is Second Vice President versary in 2012. If you have any sto- more than mere statistics of numbers Charles Sonnier Sries to share about the early years of served and miles of line. People and their ATTORNEY SLEMCO, we’d love to hear from you. memories, the difference SLEMCO has James J. Davidson, III Since its establishment in 1937, the made in their lives, the service provided EXECUTIVE STAFF Southwest Louisiana Electric Membership in good times and during natural disas- J.U. Gajan Corporation (SLEMCO) has been provid- ter—these are the most important aspects Chief Executive Officer & General Manager ing customers high quality electric service of our shared history. This upcoming Glenn Tamporello at the lowest possible cost. anniversary is the perfect opportunity to Director of Operations George Fawcett What began as a cooperative serving document your stories and preserve them Director of Marketing & Communications 256 customers along 120 miles of new for the future (Lucky Account Number Jim Laque power lines has grown over 74 years to 2038760208). -

The Journal of the Dramatists Guild of America, Inc

The Journal of the Dramatists Guild of America, Inc. The the ageissue 2016 NOV/DEC $7 USD €10 EUR www.dramatistsguild.com FrontCOVER.indd 1 10/5/16 12:57 PM To enroll, go to http://www.dginstitute.org SEP/OCTJul/Aug DGI 16 ad.indd FrontCOVERs.indd 1 2 5/23/168/8/16 1:341:52 PM VOL. 19 No 2 TABLE OF NOV/DEC 2016 2 Editor’s Notes CONTENTS 3 Dear Dramatist 4 News 7 Inspiration – KIRSTEN CHILDS 8 The Craft – KAREN HARTMAN 10 Edward Albee 1928-2016 13 “Emerging” After 50 with NANCY GALL-CLAYTON, JOSH GERSHICK, BRUCE OLAV SOLHEIM, and TSEHAYE GERALYN HEBERT, moderated by AMY CRIDER. Sidebars by ANTHONY E. GALLO, PATRICIA WILMOT CHRISTGAU, and SHELDON FRIEDMAN 20 Kander and Pierce by MARC ACITO 28 Profile: Gary Garrison with CHISA HUTCHINSON, CHRISTINE TOY JOHNSON, and LARRY DEAN HARRIS 34 Writing for Young(er) Audiences with MICHAEL BOBBITT, LYDIA DIAMOND, ZINA GOLDRICH, and SARAH HAMMOND, moderated by ADAM GWON 40 A Primer on Literary Executors – Part One by ELLEN F. BROWN 44 James Houghton: A Tribute with JOHN GUARE, ADRIENNE KENNEDY, WILL ENO, NAOMI WALLACE, DAVID HENRY HWANG, The REGINA TAYLOR, and TONY KUSHNER Dramatistis the official journal of Dramatists Guild of America, the professional organization of 48 DG Fellows: RACHEL GRIFFIN, SYLVIA KHOURY playwrights, composers, lyricists and librettists. 54 National Reports It is the only 67 From the Desk of Dramatists Guild Fund by CHISA HUTCHINSON national magazine 68 From the Desk of Business Affairs by AMY VONVETT devoted to the business and craft 70 Dramatists Diary of writing for 75 New Members theatre. -

Screen Icons Hollywood

theARTS ALEXANDER VAN DER POLL Correspondent The faces we n part one of this article published in the Nov/Dec 2010 CL, the author discussed the Ilives of some of the 20th century screen icons in depth. In this article we discuss some can’t forget more icons, and also feature a selection of fi lms and books mentioned in part one of the article with an indication of titles in the Provincial Library Service stock. SCREEN ICONS Judy Grln If I’m such a legend, why am I so lonely? of 20th (Garland). Many biographies have been written about this tragic star, each one with a slightly different angle or approach to its subject. century Lorna Luft (Garland’s daughter) wrote a particularly alternate version of the later life of Judy Garland, which was then made into a fi lm with Judy Davis taking the part of HOLLYWOOD Garland. Both the fi lm and book are worth having a look at. Others (such as the one written by Garland's last husband, Mickey Dean), seem very sentimental and one-sided. Part Two Strangely Garland’s most famous offspring, Liza Minnelli (an icon in her own right), has been very silent on the subject, mostly preferring to speak about her famous father, director Vincente Minnelli. Biographies Clarke, Gerald. Get happy: the life of Judy Garland.- Little, 2000. Deans, Mickey. Weep no more, my lady.- W.H. Allen, 1972. Edwards, Anne. Judy Garland: a biography.- Constable, 1975. Frank, Gerold. Judy.- W.H. Allen, 1975. Fricke, John. Judy Garland: world's greatest enter- tainer.- Little, 1992.