Russianjsoviet Nuclear Warhead Production

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Richard G. Hewlett and Jack M. Holl. Atoms

ATOMS PEACE WAR Eisenhower and the Atomic Energy Commission Richard G. Hewlett and lack M. Roll With a Foreword by Richard S. Kirkendall and an Essay on Sources by Roger M. Anders University of California Press Berkeley Los Angeles London Published 1989 by the University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England Prepared by the Atomic Energy Commission; work made for hire. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hewlett, Richard G. Atoms for peace and war, 1953-1961. (California studies in the history of science) Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Nuclear energy—United States—History. 2. U.S. Atomic Energy Commission—History. 3. Eisenhower, Dwight D. (Dwight David), 1890-1969. 4. United States—Politics and government-1953-1961. I. Holl, Jack M. II. Title. III. Series. QC792. 7. H48 1989 333.79'24'0973 88-29578 ISBN 0-520-06018-0 (alk. paper) Printed in the United States of America 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 CONTENTS List of Illustrations vii List of Figures and Tables ix Foreword by Richard S. Kirkendall xi Preface xix Acknowledgements xxvii 1. A Secret Mission 1 2. The Eisenhower Imprint 17 3. The President and the Bomb 34 4. The Oppenheimer Case 73 5. The Political Arena 113 6. Nuclear Weapons: A New Reality 144 7. Nuclear Power for the Marketplace 183 8. Atoms for Peace: Building American Policy 209 9. Pursuit of the Peaceful Atom 238 10. The Seeds of Anxiety 271 11. Safeguards, EURATOM, and the International Agency 305 12. -

Grappling with the Bomb: Britain's Pacific H-Bomb Tests

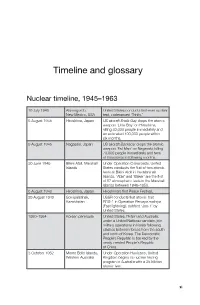

Timeline and glossary Nuclear timeline, 1945–1963 16 July 1945 Alamogordo, United States conducts first-ever nuclear New Mexico, USA test, codenamed ‘Trinity .’ 6 August 1945 Hiroshima, Japan US aircraft Enola Gay drops the atomic weapon ‘Little Boy’ on Hiroshima, killing 80,000 people immediately and an estimated 100,000 people within six months . 9 August 1945 Nagasaki, Japan US aircraft Bockscar drops the atomic weapon ‘Fat Man’ on Nagasaki, killing 70,000 people immediately and tens of thousands in following months . 30 June 1946 Bikini Atoll, Marshall Under Operation Crossroads, United Islands States conducts the first of two atomic tests at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. ‘Able’ and ‘Baker’ are the first of 67 atmospheric tests in the Marshall Islands between 1946–1958 . 6 August 1948 Hiroshima, Japan Hiroshima’s first Peace Festival. 29 August 1949 Semipalatinsk, USSR conducts first atomic test Kazakhstan RDS-1 in Operation Pervaya molniya (Fast lightning), dubbed ‘Joe-1’ by United States . 1950–1954 Korean peninsula United States, Britain and Australia, under a United Nations mandate, join military operations in Korea following clashes between forces from the south and north of Korea. The Democratic People’s Republic is backed by the newly created People’s Republic of China . 3 October 1952 Monte Bello Islands, Under Operation Hurricane, United Western Australia Kingdom begins its nuclear testing program in Australia with a 25 kiloton atomic test . xi GRAPPLING WITH THE BOMB 1 November 1952 Bikini Atoll, Marshall United States conducts its first Islands hydrogen bomb test, codenamed ‘Mike’ (10 .4 megatons) as part of Operation Ivy . -

People and Things

People and things Geoff Manning for his contributions Dirac Medal to physics applications at the Lab oratory, particularly in high energy At the recent symposium on 'Per physics, computing and the new spectives in Particle Physics' at Spallation Neutron Source. The the International Centre for Theo Rutherford Prize goes to Alan Ast- retical Physics, Trieste, ICTP Direc bury of Victoria, Canada, former tor Abdus Sa la m presided over co-spokesman of the UA 1 experi the first award ceremony for the ment at CERN. Institute's Dirac Medals. Although Philip Anderson (Princeton) and expected, Yakov Zeldovich of Abdus Sa la m (Imperial College Moscow's Institute of Space Re London and the International search was not able to attend to Centre for Theoretical Physics, receive his medal. Edward Witten Trieste) have been elected Hono of Princeton received his gold me rary Fellows of the Institute. dal alone from Antonino Zichichi on behalf of the Award Committee. Third World Prizes The 1985 Third World Academy UK Institute of Physics Awards of Sciences Physics Prize has been awarded to E. C. G. Sudarshan The Guthrie Prize and Medal of the from India for his fundamental con UK Institute of Physics this year tributions to the understanding of goes to Sir Denys Wilkinson of the weak nuclear force, in particu Sussex for his many contributions lar for his work with R. Marshak to nuclear physics. The Institute's on the theory which incorporates Glazebrook Prize goes to Ruther its parity (left/right symmetry) Friends and colleagues recently ford Appleton Laboratory director structure. -

Cambridge Five Spy Ring Part 29 of 42

192Hi _ill"I1_q :___|_ LwJ -£1 'nrrnsss usncn :.cimox~uses s1K ._ On the -RAFs'fftieth':. Kbirthda . __.t . s § 92 . '. _'.J;,'- I , -. .:_ -_i. - O 4i . 9292 ' 'i 3 rr. 1.-Ir. F - . v , . 1 < r --. , r /. I °-A --,. -:"'. " .-¢ -' . _.._=-I Il ' E; -: T -V;L I , . i ~ - . L... i -.~ - ' . i ". - - : __ . __92 - r_ .._.|._ ''|. - -5 ' .- '-' " ' f I .92. - 0-.3 1- - ' ;_. -. _. *5%"¢ " 'I! TOMORROW the ifoyalAir Forceis 50years old: As rhe-aclhellit - 1 this anniversarythe air force that was oncethe mightiest mthe /59>.°-'- 2;: y world nds its conventional strengthreduced to the level of "in..;"ff~;'::'7"1c9untrie.s._.li4i$q.I92;l!ji¢YNorth Korea, Sweden and and India. " i, < Q At present the"hittir'i'§_Foiw'v'erofthe*R.-A-¢F».-is-conce.ntr'aie_d' »'-1'.. inits-I " ageing V-bomber force. -in every other department .il'l¢.31_I§!'I__"d'5'ii"i=""""£=.r-" - has been drastic. - ' ' m""i*'" l."li"'§"-i Q 'Butdoes this matter? For in the H-bomb era, do conventional forces count? Would not any war quickly become an H-bombwar?. - O Today the Sunday Express publishes an article with an -",4-. l important hearing on these questions.it puts forward a revolu- tionary view of strategy in the years immediately ahead and , - ' _ exposes the blundersof oicial military plannersin writing-off the _',__£.:,'11 -:»;v risks of conventional war.i-.= ' I.-=1"~ 92_ ~13-:1. -

Russia Case Study

2° OIB D.N.L. Geography: Theme 2 Case study of development and inequalities in Russia PART TWO 1. A continent spanning State, rich in resources Hydrocarbon reserves Uranium Gold, diamonds Iron and non-ferrous metals Cultivated land (cereals) Taiga and conifer forests Towns (enabling resource exploitation) Polar Tundra and mountains Permanent Ice banks Permafrost limit 2. Photograph of the city of Norilsk, a degraded environmental inheritance from the Soviet Union: Norilsk is an industrial town expanded by Stalin in 1935 to exploit minerals. Today the Norilsk Nickel Company produces 20% of all nickel in the world. Life expectancy for the workers is 10 years less than the Russian average. Learn more about the closed city of Norilsk here: http://theprotocity.com/norilsk_closed_cit/ Watch this excellent, sad, moving video about Norilsk here: (11m): https://www.theatlantic.com/video/index/545228/my-deadly-beautiful-city-norilsk/ 3. Demographic and socio-economic challenges facing Russia - Lack of manpower - Russia, which currently has a population of 146.9 million, has lost more than five million inhabitants since 1991, a consequence of the serious demographic crisis that followed the fall of the Soviet Union. The first generation born in the post-Soviet years, which were marked by a declining birth rate, is now entering the labour market, which is likely to see a shortage of qualified manpower and a resultant curb on economic growth. - Retirement age - The retirement age in Russia -- 55 for women and 60 for men -- is among the lowest in the world. While state pensions are very low, with the demographic decline the system still represents a growing burden for the federal budget…. -

Article Thermonuclear Bomb 5 7 12

1 Inexpensive Mini Thermonuclear Reactor By Alexander Bolonkin [email protected] New York, April 2012 2 Article Thermonuclear Reactor 1 26 13 Inexpensive Mini Thermonuclear Reactor By Alexander Bolonkin C&R Co., [email protected] Abstract This proposed design for a mini thermonuclear reactor uses a method based upon a series of important innovations. A cumulative explosion presses a capsule with nuclear fuel up to 100 thousands of atmospheres, the explosive electric generator heats the capsule/pellet up to 100 million degrees and a special capsule and a special cover which keeps these pressure and temperature in capsule up to 0.001 sec. which is sufficient for Lawson criteria for ignition of thermonuclear fuel. Major advantages of these reactors/bombs is its very low cost, dimension, weight and easy production, which does not require a complex industry. The mini thermonuclear bomb can be delivered as a shell by conventional gun (from 155 mm), small civil aircraft, boat or even by an individual. The same method may be used for thermonuclear engine for electric energy plants, ships, aircrafts, tracks and rockets. ----------------------------------------------------------------------- Key words: Thermonuclear mini bomb, thermonuclear reactor, nuclear energy, nuclear engine, nuclear space propulsion. Introduction It is common knowledge that thermonuclear bombs are extremely powerful but very expensive and difficult to produce as it requires a conventional nuclear bomb for ignition. In stark contrast, the Mini Thermonuclear Bomb is very inexpensive. Moreover, in contrast to conventional dangerous radioactive or neutron bombs which generates enormous power, the Mini Thermonuclear Bomb does not have gamma or neutron radiation which, in effect, makes it a ―clean‖ bomb having only the flash and shock wave of a conventional explosive but much more powerful (from 1 ton of TNT and more, for example 100 tons). -

The Russian-A(Merican) Bomb: the Role of Espionage in the Soviet Atomic Bomb Project

J. Undergrad. Sci. 3: 103-108 (Summer 1996) History of Science The Russian-A(merican) Bomb: The Role of Espionage in the Soviet Atomic Bomb Project MICHAEL I. SCHWARTZ physicists and project coordinators ought to be analyzed so as to achieve an understanding of the project itself, and given the circumstances and problems of the project, just how Introduction successful those scientists could have been. Third and fi- nally, the role that espionage played will be analyzed, in- There was no “Russian” atomic bomb. There only vestigating the various pieces of information handed over was an American one, masterfully discovered by by Soviet spies and its overall usefulness and contribution Soviet spies.”1 to the bomb project. This claim echoes a new theme in Russia regarding Soviet Nuclear Physics—Pre-World War II the Soviet atomic bomb project that has arisen since the democratic revolution of the 1990s. The release of the KGB As aforementioned, Paul Josephson believes that by (Commissariat for State Security) documents regarding the the eve of the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, Soviet sci- role that espionage played in the Soviet atomic bomb project entists had the technical capability to embark upon an atom- has raised new questions about one of the most remark- ics weapons program. He cites the significant contributions able and rapid scientific developments in history. Despite made by Soviet physicists to the growing international study both the advanced state of Soviet nuclear physics in the of the nucleus, including the 1932 splitting of the lithium atom years leading up to World War II and reported scientific by proton bombardment,7 Igor Kurchatov’s 1935 discovery achievements of the actual Soviet atomic bomb project, of the isomerism of artificially radioactive atoms, and the strong evidence will be provided that suggests that the So- fact that L. -

Jihadists and Nuclear Weapons

VERSION: Charles P. Blair, “Jihadists and Nuclear Weapons,” in Gary Ackerman and Jeremy Tamsett, eds., Jihadists and Weapons of Mass Destruction: A Growing Threat (New York: Taylor and Francis, 2009), pp. 193-238. c h a p t e r 8 Jihadists and Nuclear Weapons Charles P. Blair CONTENTS Introduction 193 Improvised Nuclear Devices (INDs) 195 Fissile Materials 198 Weapons-Grade Uranium and Plutonium 199 Likely IND Construction 203 External Procurement of Intact Nuclear Weapons 204 State Acquisition of an Intact Nuclear Weapon 204 Nuclear Black Market 212 Incidents of Jihadist Interest in Nuclear Weapons and Weapons-Grade Nuclear Materials 213 Al-Qa‘ida 213 Russia’s Chechen-Led Jihadists 214 Nuclear-Related Threats and Attacks in India and Pakistan 215 Overall Likelihood of Jihadists Obtaining Nuclear Capability 215 Notes 216 Appendix: Toward a Nuclear Weapon: Principles of Nuclear Energy 232 Discovery of Radioactive Materials 232 Divisibility of the Atom 232 Atomic Nucleus 233 Discovery of Neutrons: A Pathway to the Nucleus 233 Fission 234 Chain Reactions 235 Notes 236 INTRODUCTION On December 1, 2001, CIA Director George Tenet made a hastily planned, clandestine trip to Pakistan. Tenet arrived in Islamabad deeply shaken by the news that less than three months earlier—just weeks before the attacks of September 11, 2001—al-Qa‘ida and Taliban leaders had met with two former Pakistani nuclear weapon scientists in a joint quest to acquire nuclear weapons. Captured documents the scientists abandoned as 193 AU6964.indb 193 12/16/08 5:44:39 PM 194 Charles P. Blair they fled Kabul from advancing anti-Taliban forces were evidence, in the minds of top U.S. -

Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Intelligence

Russia • Military / Security Historical Dictionaries of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, No. 5 PRINGLE At its peak, the KGB (Komitet Gosudarstvennoy Bezopasnosti) was the largest HISTORICAL secret police and espionage organization in the world. It became so influential DICTIONARY OF in Soviet politics that several of its directors moved on to become premiers of the Soviet Union. In fact, Russian president Vladimir V. Putin is a former head of the KGB. The GRU (Glavnoe Razvedvitelnoe Upravleniye) is the principal intelligence unit of the Russian armed forces, having been established in 1920 by Leon Trotsky during the Russian civil war. It was the first subordinate to the KGB, and although the KGB broke up with the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the GRU remains intact, cohesive, highly efficient, and with far greater resources than its civilian counterparts. & The KGB and GRU are just two of the many Russian and Soviet intelli- gence agencies covered in Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Intelligence. Through a list of acronyms and abbreviations, a chronology, an introductory HISTORICAL DICTIONARY OF essay, a bibliography, and hundreds of cross-referenced dictionary entries, a clear picture of this subject is presented. Entries also cover Russian and Soviet leaders, leading intelligence and security officers, the Lenin and Stalin purges, the gulag, and noted espionage cases. INTELLIGENCE Robert W. Pringle is a former foreign service officer and intelligence analyst RUSSIAN with a lifelong interest in Russian security. He has served as a diplomat and intelligence professional in Africa, the former Soviet Union, and Eastern Europe. For orders and information please contact the publisher && SOVIET Scarecrow Press, Inc. -

Chapter 6 the Aftermath of the Cambridge-Vienna Controversy: Radioactivity and Politics in Vienna in the 1930S

Trafficking Materials and Maria Rentetzi Gendered Experimental Practices Chapter 6 The Aftermath of the Cambridge-Vienna Controversy: Radioactivity and Politics in Vienna in the 1930s Consequences of the Cambridge-Vienna episode ranged from the entrance of other 1 research centers into the field as the study of the atomic nucleus became a promising area of scientific investigation to the development of new experimental methods. As Jeff Hughes describes, three key groups turned to the study of atomic nucleus. Gerhard Hoffman and his student Heinz Pose studied artificial disintegration at the Physics Institute of the University of Halle using a polonium source sent by Meyer.1 In Paris, Maurice de Broglie turned his well-equipped laboratory for x-ray research into a center for radioactivity studies and Madame Curie started to accumulate polonium for research on artificial disintegration. The need to replace the scintillation counters with a more reliable technique also 2 led to the extensive use of the cloud chamber in Cambridge.2 Simultaneously, the development of electric counting methods for measuring alpha particles in Rutherford's laboratory secured quantitative investigations and prompted Stetter and Schmidt from the Vienna Institute to focus on the valve amplifier technique.3 Essential for the work in both the Cambridge and the Vienna laboratories was the use of polonium as a strong source of alpha particles for those methods as an alternative to the scintillation technique. Besides serving as a place for scientific production, the laboratory was definitely 3 also a space for work where tasks were labeled as skilled and unskilled and positions were divided to those paid monthly and those supported by grant money or by research fellowships. -

Jagd Auf Die Klügsten Köpfe

1 DEUTSCHLANDFUNK Redaktion Hintergrund Kultur / Hörspiel Redaktion: Ulrike Bajohr Dossier Jagd auf die klügsten Köpfe. Intellektuelle Zwangsarbeit deutscher Wissenschaftler in der Sowjetunion. Ein Feature von Agnes Steinbauer 12:30-13:15 Sprecherin: An- und Absage/Text: Edda Fischer 13:10-13:45 Sprecher 1: Zitate, Biografien Thomas Lang Sprecher 2: An- und Absage/Zwischentitel/ ov russisch: Lars Schmidtke (HSP) Produktion: 01. /02 August 2011 ab 12:30 Studio: H 8.1 Urheberrechtlicher Hinweis Dieses Manuskript ist urheberrechtlich geschützt und darf vom Empfänger ausschließlich zu rein privaten Zwecken genutzt werden. Die Vervielfältigung, Verbreitung oder sonstige Nutzung, die über den in §§ 44a bis 63a Urheberrechtsgesetz geregelten Umfang hinausgeht, ist unzulässig. © - unkorrigiertes Exemplar - Sendung: Freitag, d. 05.August 2011, 19.15 – 2 01aFilmton russisches Fernsehen) Beginn bei ca 15“... Peenemünde.... Wernher von Braun.... nach ca 12“(10“) verblenden mit Filmton 03a 03a 0-Ton Boris Tschertok (russ./ Sprecher 2OV ) Im Oktober 1946 wurde beschlossen, über Nacht gleichzeitig alle nützlichen deutschen Mitarbeiter mit ihren Familien und allem, was sie mitnehmen wollten, in die UdSSR zu transportieren, unabhängig von ihrem Einverständnis. Filmton 01a hoch auf Stichwort: Hitler....V2 ... bolschoi zaschtschitny zel darauf: 03 0-Ton Karlsch (Wirtschaftshistoriker): 15“ So können wir sagen, dass bis zu 90 Prozent der Wissenschaftler und Ingenieure, die in die Sowjetunion kamen, nicht freiwillig dort waren, sondern sie hatten keine Chance dem sowjetischen Anliegen auszuweichen. Filmton 01a bei Detonation hoch und weg Ansage: Jagd auf die klügsten Köpfe. Intellektuelle Zwangsarbeit deutscher Wissenschaftler in der Sowjetunion. Ein Feature von Agnes Steinbauer 3 04 0-Ton Helmut Wolff 57“ Am 22.Oktober frühmorgens um vier klopfte es recht heftig an die Tür, und vor der Wohnungstür stand ein sowjetischer Offizier mit Dolmetscherin, rechts und links begleitet von zwei sowjetischen Soldaten mit MPs im Anschlag. -

What's So Bad About Norilsk Nickel Factory?

Norilsk Nickel Factory Transforming the City of Horror Location: Norilsk, Krasnoyarsk Krai, Russia Population affected: 177,506 Macaulay Honors College Students: Alasdair McLean, Ellianna Schwab, Kevin Call, Revital Schechter Instructor: Dr. Angelo Lampousis, Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, City College of New York, CUNY Introduction Challenges to Fixing the Situation A former Soviet Gulag camp, Norilsk is now a long forgotten, poverty-stricken town in the Arctic Circle. The one hundred seventy-seven thousand residents live in a nearly uninhabitable climate, but it is something else that truly endangers them. N • Norilsk Nickel is a prime employer in the city, so a majority of residents rely on the The city, located in the Krasnoyarsk Krai region of Russia, is home to one of the world’s largest suppliers of heavy metals, 6 Norilsk Nickel. This massive company does little to temper its environmental impact, blighting the surrounding wildlife factory as a source of income, even though they are not paid fair wages. despite numerous calls of action from federal agencies and local support. Currently the company is estimated to produce • The city itself is remote and hard to reach, located 200 km north of the Arctic Circle, 6 1% (2x106 tons) of global sulfur dioxide emissions, a gas that is known to cause acid rain and respiratory problems to those causing it to be naturally isolated. exposed. The health of Norilsk’s residents is directly impacted, indicated by a life expectancy of only 46 years. Although • In 2001, Norilsk was declared a closed city once again. The government does not allow tourists to come in, and the only visitors must be invited by the government or have citizens of Norilsk recognize the hazards of where they live, the greater majority of the population is incapable of leaving 11 due to extreme poverty.