Pigeon Pie, Anyone?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Whistler3 Frontcover

The Whistler is the occasionally issued journal of the Hunter Bird Observers Club Inc. ISSN 1835-7385 The aims of the Hunter Bird Observers Club (HBOC), which is affiliated with Bird Observation and Conservation Australia, are: To encourage and further the study and conservation of Australian birds and their habitat To encourage bird observing as a leisure-time activity HBOC is administered by a Committee: Executive: Committee Members: President: Paul Baird Craig Anderson Vice-President: Grant Brosie Liz Crawford Secretary: Tom Clarke Ann Lindsey Treasurer: Rowley Smith Robert McDonald Ian Martin Mick Roderick Publication of The Whistler is supported by a Sub-committee: Mike Newman (Joint Editor) Harold Tarrant (Joint Editor) Liz Crawford (Production Manager) Chris Herbert (Cover design) Liz Huxtable Ann Lindsey Jenny Powers Mick Roderick Alan Stuart Authors wishing to submit manuscripts for consideration for publication should consult Instructions for Authors on page 61 and submit to the Editors: Mike Newman [email protected] and/or Harold Tarrant [email protected] Authors wishing to contribute articles of general bird and birdwatching news to the club newsletter, which has 6 issues per year, should submit to the Newsletter Editor: Liz Crawford [email protected] © Hunter Bird Observers Club Inc. PO Box 24 New Lambton NSW 2305 Website: www.hboc.org.au Front cover: Australian Painted Snipe Rostratula australis – Photo: Ann Lindsey Back cover: Pacific Golden Plover Pluvialis fulva - Photo: Chris Herbert The Whistler is proudly supported by the Hunter-Central Rivers Catchment Management Authority Editorial The Whistler 3 (2009): i-ii The Whistler – Editorial The Editors are pleased to provide our members hopefully make good reading now, but will and other ornithological enthusiasts with the third certainly provide a useful point of reference for issue of the club’s emerging journal. -

Trad Biocontrol Pigeons and Doves

WINTER 2017 Issue 74 Pittwater Natural Heritage Association - thinking locally, acting locally Trad Biocontrol Pigeons and Doves Trad, formerly Wandering Jew, is a nightmare weed of bush- What’s the difference? Nothing really, as the two terms are land and gardens. But maybe help is coming. often used interchangeably. A subspecies of the Rock Dove is the A biocontrol agent Kordyana brasiliensis for Trad Tradescantia Feral or Domestic Pigeon. In general “dove” is used for smaller fluminensis has been tested by CSIRO and an application for re- birds than “pigeon”. They belong to the bird family Columbidae. lease has been submitted to the Australian Government . Trad is native to Brazil. The biocontrol agent is a leaf smut fungus Crested Pigeon also native to Brazil. Host specificity testing of the fungus is on- going in the CSIRO Canberra quarantine facility. This is to ensure that Trad is the only plant the fungus will survive on, therefore safe to release. Initial results are highly promising and it is hoped this fungus will eventually get permission to be released in Australia. If success- ful it may be available for release in about a year. Requirements for release sites are likely to include Stopping other forms of Trad control (i.e. weeding) Monitoring Support of land manager (possibly small financial contribution to help fund supply of the fungus). References: Louise Moran, Using pathogens to biologically con- To feed their nestlings both male and females produce “crop trol environmental weeds – updates. Plant Protection Quarterly. milk” to feed their young; only flamingos and some penguins also 2015;30(3):82-85 feed their young this way. -

Crested Barbary Dove (Streptopelia Risoria) in Pet Shop of Kushtia, Bangladesh

Journal of Dairy, Veterinary & Animal Research Short Communication Open Access Crested Barbary dove (streptopelia risoria) in pet shop of kushtia, Bangladesh Short communication Volume 8 Issue 4 - 2019 Crested fancy pigeons or pigeons are very common in Bangladesh but this is rare in doves. A shop in Kushtia district of Bangladesh, Ashraful Kabir M Department of Biology, Saidpur Cantonment Public College, they collected one wild type but crested Barbary Dove from Khulna Bangladesh and another white crested form from an unknown locality. Crowned pigeons are not available in Bangladesh. Only in Chittagong, Correspondence: M Ashraful Kabir, Department of Biology, Comilla, and Dhaka there some birds were found. From the personal Saidpur Cantonment Public College, Bangladesh, communication with the rearers, they said that productivity of those Email crested pigeons is very slow. In nature, Topknot and Pheasant Pigeons Received: March 07, 2019 | Published: August 30, 2019 have tuft and occipital crest. History says, selective breeding of fancy pigeons in Egypt they produced lots of crested pigeon varieties but this was not common in dove. Crested Choiseul Pigeon was extinct and now only Australian Crested Dove have upright crest. Selective breeding may produce huge crests in dove. Pigeons have various pattern of feather which created abnormal size or position of the feathers.1 Huge feathers of head cover the head and eyes and feather Goura victoria, Western- Goura cristata and Southern- Goura in legs and feet is muff. Most of the time abnormal feathers can cause scheepmakeri) are still surviving in the world (Plates 2‒4). difficulties in feeding, perching, flying, and breeding. -

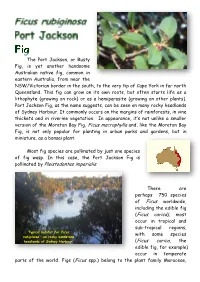

Pollinated by Pleistodontes Imperialis. (Ficus Carica); Most

The Port Jackson, or Rusty Fig, is yet another handsome Australian native fig, common in eastern Australia, from near the NSW/Victorian border in the south, to the very tip of Cape York in far north Queensland. This fig can grow on its own roots, but often starts life as a lithophyte (growing on rock) or as a hemiparasite (growing on other plants). Port Jackson Fig, as the name suggests, can be seen on many rocky headlands of Sydney Harbour. It commonly occurs on the margins of rainforests, in vine thickets and in riverine vegetation. In appearance, it’s not unlike a smaller version of the Moreton Bay Fig, Ficus macrophylla and, like the Moreton Bay Fig, is not only popular for planting in urban parks and gardens, but in miniature, as a bonsai plant. Most fig species are pollinated by just one species of fig wasp. In this case, the Port Jackson Fig is pollinated by Pleistodontes imperialis. There are perhaps 750 species of Ficus worldwide, including the edible fig (Ficus carica); most occur in tropical and sub-tropical regions, Typical habitat for Ficus with some species rubiginosa – on rocky sandstone headlands of Sydney Harbour. (Ficus carica, the edible fig, for example) occur in temperate parts of the world. Figs (Ficus spp.) belong to the plant family Moraceae, which also includes Mulberries (Morus spp.), Breadfruit and Jackfruit (Artocarpus spp.). Think of a mulberry, and imagine it turned inside out. This might perhaps bear some resemblance to a fig. Ficus rubiginosa growing on a sandstone platform adjoining mangroves. Branches of one can be seen in the foreground, a larger one at the rear. -

The Role of Habitat Variability and Interactions Around Nesting Cavities in Shaping Urban Bird Communities

The role of habitat variability and interactions around nesting cavities in shaping urban bird communities Andrew Munro Rogers BSc, MSc Photo: A. Rogers A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2018 School of Biological Sciences Andrew Rogers PhD Thesis Thesis Abstract Inter-specific interactions around resources, such as nesting sites, are an important factor by which invasive species impact native communities. As resource availability varies across different environments, competition for resources and invasive species impacts around those resources change. In urban environments, changes in habitat structure and the addition of introduced species has led to significant changes in species composition and abundance, but the extent to which such changes have altered competition over resources is not well understood. Australia’s cities are relatively recent, many of them located in coastal and biodiversity-rich areas, where conservation efforts have the opportunity to benefit many species. Australia hosts a very large diversity of cavity-nesting species, across multiple families of birds and mammals. Of particular interest are cavity-breeding species that have been significantly impacted by the loss of available nesting resources in large, old, hollow- bearing trees. Cavity-breeding species have also been impacted by the addition of cavity- breeding invasive species, increasing the competition for the remaining nesting sites. The results of this additional competition have not been quantified in most cavity breeding communities in Australia. Our understanding of the importance of inter-specific interactions in shaping the outcomes of urbanization and invasion remains very limited across Australian communities. This has led to significant gaps in the understanding of the drivers of inter- specific interactions and how such interactions shape resource use in highly modified environments. -

OBSERVATIONS on the DIET of the TOPKNOT PIGEON Lopholaimus Antarcticus in the ILLAWARRA RAINFOREST, NEW SOUTH WALES

OSEAIOS O E IE O E OKO IGEO phl I E IAWAA AIOES EW SOU WAES ntrt , R. D. WATERHOUSE 4/1-5 Ada Street, Oatley, New South Wales 2223 vd: 2 Otbr Obrvtn r d n th fdn bhvr f pnt n Lopholaimus antarcticus fr Mrh 88 t br 2 nr Mt Kr, Wllnn, Sth Wl. h p f plnt tht ntrbtd frt t th dt r rrdd fr h nth f th r. h nlt, ntt nd drtn f frtn b fd p vrd ndrbl vr th td prd. pnt n r fnd t n th frt f rnfrt p nd th tht ntrbtd t t th prn f th brd n th td r r th Cbb r l vtn trl, Mrtn rphll, rn h nnnt nnnh, d Crptr ln, Wht Chrr Shzr vt, pprvn pr nvhllnd nd llpll An th. h r rndd fr rnfrt rvttn h n th Wllnn r. INTRODUCTION 3. to identify 'key' species that could supplement the natural food supplies available locally to Topknot The Topknot Pigeon Lopholaimus antarcticus is a Pigeons as well as other rainforest birds. monotypic Australian endemic which formerly ranged in large flocks, mainly in rainforests along the east coast and Topknot Pigeons were formerly very wary in the region tablelands from Cape York to southern New South Wales due to being hunted extensively until the 1930s. Even (Morris et al. 1981; Pizzey and Knight 1997). today, some illegal shooting takes place in the Illawarra district (D. Rosso, pers. comm.) but no longer occurs in Although at one time reported in flocks of three to five the vicinity of the Mount Keira Scout Camp (D. -

A Preliminary Assessment of Faunal Values Within and Adjacent EPC 1029, Styx Basin, Central-East Queensland

A preliminary assessment of faunal values within and adjacent EPC 1029, Styx Basin, central-east Queensland ) Prepared for Yeats Consulting Engineers by Ed Meyer, Ecological Consultant,S Luscombe Street, Runcorn QLD 4113 ([email protected]) Conditions of use This report may only be used for the purposes for which it was commissioned. The use of this report, or part thereof, for any other reason or purpose is prohibited without the written consent of the author. Front cover: Fauna recorded from EPC 1029 during March 2011 surveys. Clockwise from upper left: ornamental snake (Denisonia maculata); squatter pigeon (southern race) (Geophaps scripta scripta); metallic snake-eyed skink (Cryptoblepharus metal/icus); and eastern sedgefrog (Litoria tal/ax). ©Edward Meyer 2011 5 Luscombe Street, Runcorn QLD 4113 E-mail:[email protected] Version 2 _ 3 August 2011 2 Table of contents 1. Summary 4 2. Background 6 Description of study area 6 Nomenclature 6 Abbreviations and acronyms 7 3. Methodology 9 General approach 9 ) Desktop assessment 9 Likelihood of occurrence assessments 10 Field surveys 11 Survey conditions 15 Survey limitations 15 4. Results 17 Desktop assessment findings 17 Likelihood of occurrence assessments 17 Field survey results -fauna 20 Field survey results - fauna habitat 22 Habitat for conservation significant species 28 ) 5. Summary and conclusions 37 6. References 38 Appendix A: Fauna previously recorded from Desktop Assessment Study Area 41 Appendix B: likelihood of occurrence assessments for conservation significant fauna 57 Appendix C: March 2011 survey results 73 Appendix D: Habitat photos 85 Appendix E: Habitat assessment proforma 100 3 1. Summary The faunal values of land within and adjacent Exploration Permit for Coal (EPe) 1029 were investigated by way of desktop review of existing information as well as field surveys carried out in late March 201l. -

Assessing the Sustainability of Native Fauna in NSW State of the Catchments 2010

State of the catchments 2010 Native fauna Technical report series Monitoring, evaluation and reporting program Assessing the sustainability of native fauna in NSW State of the catchments 2010 Paul Mahon Scott King Clare O’Brien Candida Barclay Philip Gleeson Allen McIlwee Sandra Penman Martin Schulz Office of Environment and Heritage Monitoring, evaluation and reporting program Technical report series Native vegetation Native fauna Threatened species Invasive species Riverine ecosystems Groundwater Marine waters Wetlands Estuaries and coastal lakes Soil condition Land management within capability Economic sustainability and social well-being Capacity to manage natural resources © 2011 State of NSW and Office of Environment and Heritage The State of NSW and Office of Environment and Heritage are pleased to allow this material to be reproduced in whole or in part for educational and non-commercial use, provided the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are acknowledged. Specific permission is required for the reproduction of photographs. The Office of Environment and Heritage (OEH) has compiled this technical report in good faith, exercising all due care and attention. No representation is made about the accuracy, completeness or suitability of the information in this publication for any particular purpose. OEH shall not be liable for any damage which may occur to any person or organisation taking action or not on the basis of this publication. Readers should seek appropriate advice when applying the information to -

Pigeon and Dove CAMP 1993.Pdf

CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR PIGEONS AND DOVES Report from a Workshop held 10-13 March 1993 San Diego, CA Edited by Bill Toone, Sue Ellis, Roland Wirth, Ann Byers, and Ulysses Seal Compiled by the Workshop Participants A Collaborative Effort of the ICBP Pigeon and Dove Specialist Group IUCN/SSC Captive Breeding Specialist Group Bi?/rire·INTERNATIONAL The work of the Conservation Breeding Specialist Group is made possible by generous contributions from the following members of the CBSG Institutional Conservation Council Conservators ($10,000 and above) Fort Wayne Zoological Society Banham Zoo Belize Zoo Australasian Species Management Program Gladys Porter Zoo Copenhagen Zoo Claws 'n Paws Chicago Zoological Society Indianapolis Zoological Society Cotswold Wildlife Park Darmstadt Zoo Columbus Zoological Gardens International Aviculturists Society Dutch Federation of Zoological Gardens Dreher Park Zoo Denver Zoological Gardens Japanese Association of Zoological Parks Erie Zoological Park Fota Wildlife Park Fossil Rim Wildlife Center and Aquariums Fota Wildlife Park Great Plains Zoo Friends of Zoo Atlanta Jersey Wildlife Preservation Trust Givskud Zoo Hancock House Publisher Greater Los Angeles Zoo Association Lincoln Park Zoo Granby Zoological Society Kew Royal Botanic Gardens International Union of Directors of The Living Desert International Zoo Veterinary Group Lisbon Zoo Zoological Gardens Marwell Zoological Park Knoxville Zoo Miller Park Zoo Metropolitan Toronto Zoo Milwaukee County Zoo National Geographic Magazine Nagoya Aquarium Minnesota Zoological Garden NOAHS Center National Zoological Gardens National Audubon Society-Research New York Zoological Society North of England Zoological Society, of South Africa Ranch Sanctuary Omaha's Henry Doody Zoo Chester Zoo Odense Zoo National Aviary in Pittsburgh Saint Louis Zoo Oklahoma City Zoo Orana Park Wildlife Trust Parco Faunistico "La Torbiera" Sea World, Inc. -

Climate Change Threatens a Fig-Frugivore Mutualism at Its Drier, Western Range Margin

Climate Change Threatens a Fig-Frugivore Mutualism at its Drier, Western Range Margin K. DAVID MACKAY* AND C.L. GROSS Ecosystem Management, University of New England, Armidale NSW 2351 Australia * Author for correspondence: [email protected] Keywords: keystone, Ficus, dry rainforest, range shifts, heat-waves, population decline Published on 10 April 2019 at https://openjournals.library.sydney.edu.au/index.php/LIN/index Mackay, K.D. and Gross, C.L.(2019). Climate change threatens a fi g-frugivore mutualism at its drier, western range margin. Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales 141:S1-S17. Ficus rubiginosa (the Rusty Fig; Moraceae) provides a keystone food resource for a diverse array of vertebrate frugivores in eastern Australia. These frugivores, in turn, provide vital seed-dispersal services to the fi g. The aims of this study were to investigate impacts of population size and climatic variation on avian- frugivore visitation to F. rubiginosa at the extreme western, drier margin of the species’ range. Eighty-two bird species visited F. rubiginosa trees in this three-year study. Twenty-nine species were frugivores or omnivorous frugivore/insectivores. The number of ripe fruit in a tree had the greatest positive infl uence on frugivore visitation (p < 0.0001). Fig-population size infl uenced the assemblage of frugivore species visiting trees but not the number of frugivores or the rate of frugivore visitation. The number of ripe fruit in a tree was negatively associated with declines in rainfall, to total losses of standing crops through dieback and lack of crop initiation. Predicted long-term declines in rainfall across this region of eastern Australia and increased incidence of drought will lead to reduced crop sizes in F. -

Ficus Seed Dispersal Guilds: Ecology, Evolution and Conservation Implications

Ficus seed dispersal guilds: ecology, evolution and conservation implications MICHAEL J. SHANAHAN Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation School of Biology December 2000 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly, I wish to thank my supervisor, Dr Steve Compton, for initially turning me on to the genus Ficus and for his guidance throughout my doctorate, especially during the write-up period. This research was conducted whilst I was a visiting research fellow at the Institute of Biodiversity and Environmental Conservation (IBEC) at Universiti Malaysia Sarawak (UNIMAS). For my appointment to this post I thank Professor Ghazally Ismail and Dr Stuart Davies and, for administrative help at UNIMAS, Yaziz and Dayang. Fieldwork conducted in Sarawak was undertaken with permission of the Forest Department Sarawak and for this I thank, in particular, Abdul Abang Hj. Hamid and Sapuan Hj. Ahmad. Logistical support in Lambir was provided by Johan and Mr Abdullah. Canopy studies were greatly aided by permission to use the walkways and towers of the Canopy Biology Program in Sarawak and I wish to acknowledge the assistance of Professor Tohru Nakashizuka and the late Professor Tamiji Inoue. For permission to live in the "American house" in Lambir I am grateful to the Center for Tropical Forest Science (Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute) and in particular, Drs Jim La Frankie and Elizabeth Losos. My work in Borneo was greatly aided by my first-rate research assistant Siba anak Aji whose constant hard work and high spirits were an inspiration to me. -

Creating Stepping Stones for Frugivores TIN Topic 14

Creating Stepping Stones for Frugivores TIN Topic 14 Ideally, in natural area restoration we have large bushland areas within which we are working to re- establish on-site habitat or wildlife corridors to even more extensive areas of native wildlife habitat. The reality is often much less than this: we are working in narrow urban riparian reserves infested with Lantana, Privet, Bitou and Camphor Laurel, or we only have our own backyard in which to work. Even so, you can still make a substantial contribution to protection of native wildlife in your area by creating a “stepping stone” oasis for fruit-eating (frugivorous) wildlife. Over time, because of loss of native fruiting species, birds and bats have become semi-dependent on weed species; a situation which could become self-perpetuating because they then become an agent for spreading these weed species (Camphor Laurel, for example). By gradual and mosaic removal of weeds, and replacement with local native species, the balance can be tipped in favour of the local plant species, without compromising the food source for native wildlife. Gradual removal of weed and exotic garden species and replacement with the local suggestions would provide a food source for the following local frugivores; Grey-headed Flying Fox (Pteropus poliocephalus), Brown Pigeon Macropygia amboinensis, Rose-crowned Fruit-dove Ptilinopus regina, Superb Fruit-dove Ptilinopus superbus, Wompoo Fruit-dove Ptilinopus magnificus, White- headed Fruit Pigeon (Columba norfolciensis), Topknot Pigeon (Lopholaimus antarcticus), Olive-backed Oriole (Oriolus sagittatus), Southern Figbird (Sphecotheres vieilloti), Regent Bowerbird (Sericulus chrysocephalus) and Satin Bowerbird (Ptilonorhynchus violaceus), some of which are threatened species.