Evaluating the Levels of Service Delivery in the Matjabeng Local Municipality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Provincial Gazette Provinsiale Koerant

Provincial Provinsiale Gazette Koerant Free State Province Provinsie Vrystaat Published by Authority Uitgegee op Gesag NO. 48 FRIDAY, 02 AUGUST 2019 NR.48 VRYDAG, 02 AUGUSTUS 2019 PROVINCIAL NOTICES 72 Nketoana Local Municipality: 72 Nketoana Plaaslike Munisipaliteit: Notice of 2019/20120 Municipal Tariffs................. 2 Kennisgewing van 2019/20120 Munisipale Tariewe...... 2 GENERAL NOTICES ALGEMENE KENNISGEWINGS 69 Mangaung Municipal Land Use Planning By-Law: 69 Mangaung Munisipale Grongebruik-Beplanning By- Erf 13440 Bloemfontein (Oranjesig)................... 2 Wet: Erf 13440 Bloemfontein (Oranjesig)................... 2 70 Removal of Restrictive Condition of Title: 70 Ophef van Beperkende Voorwaarde uit Akte: (A) Portion 1 of Erf 133 Langenhoven Park, (A) Gedeelte 1 van Erf 133 Langenhoven Park, District Bloemfontein Distrik Bloemfontein (B) Plot 8 Pantydefaid Small Holdings, District (B) Plot 8 Pantydefaid Small Holdings, Distrik Bloemfontein... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... .... 3 Bloemfontein................................................. 3 71 Mangaung Municipal Land Use Planning By-Law: 71 Mangaung Munisipale Grondgebruik-Beplanning By Erf 3446, 67 Genl. Dan Pienaar Drive, Wet: Erf 3446, 67 Genl. Dan Pienaar Drive, Bloemfontein... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ........ ..... 3 Bloemfontein........................................................ 3 72 Phumelela By-Law on Municipal Land Use Planning, 2017: Vrede: Rezoning: Erven 1115, 1117 and 1118 .............................................. -

Public Libraries in the Free State

Department of Sport, Arts, Culture & Recreation Directorate Library and Archive Services PUBLIC LIBRARIES IN THE FREE STATE MOTHEO DISTRICT NAME OF FRONTLINE TYPE OF LEVEL OF TOWN/STREET/STREET STAND GPS COORDINATES SERVICES RENDERED SPECIAL SERVICES AND SERVICE STANDARDS POPULATION SERVED CONTACT DETAILS REGISTERED PERIODICALS AND OFFICE FRONTLINE SERVICE NUMBER NUMBER PROGRAMMES CENTER/OFFICE MANAGER MEMBERS NEWSPAPERS AVAILABLE IN OFFICE LIBRARY: (CHARTER) Bainsvlei Public Library Public Library Library Boerneef Street, P O Information and Reference Library hours: 446 142 Ms K Niewoudt Tel: (051) 5525 Car SA Box 37352, Services Ma-Tue, Thu-Fri: 10:00- (Metro) 446-3180 Fair Lady LANGENHOVENPARK, Outreach Services 17:00 Fax: (051) 446-1997 Finesse BLOEMFONTEIN, 9330 Electronic Books Wed: 10:00-18:00 karien.nieuwoudt@mangau Hoezit Government Info Services Sat: 8:30-12:00 ng.co.za Huisgenoot Study Facilities Prescribed books of tertiary Idees Institutions Landbouweekblad Computer Services: National Geographic Internet Access Rapport Word Processing Rooi Rose SA Garden and Home SA Sports Illustrated Sarie The New Age Volksblad Your Family Bloemfontein City Public Library Library c/o 64 Charles Information and Reference Library hours: 443 142 Ms Mpumie Mnyanda 6489 Library Street/West Burger St, P Services Ma-Tue, Thu-Fri: 10:00- (Metro) 051 405 8583 Africa Geographic O Box 1029, Outreach Services 17:00 Architect and Builder BLOEMFONTEIN, 9300 Electronic Books Wed: 10:00-18:00 Tel: (051) 405-8583 Better Homes and Garden n Government Info -

Downloads/Theory of Change ENG

University of Fort Hare Topic: A Critical Assessment of the Provincial Intervention Outcomes in Makana Local Municipality in the Eastern Cape Province (2012- 2014) By Zolani Teyisi Project Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree in Master of Administration In the Faculty of Management and Commerce Department of Public Administration University of Fort Hare Alice Supervisor: Professor Nzewi OI November 2016 DECLARATION I declare that the dissertation hereby submitted in the fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Masters Public Administration at the University of Fort Hare is my own work and has not been previously submitted in any university by anyone else for the fulfillment of a degree. Name……………………………..... Date……………………………. Signature……………………………. i DEDICATIONS Le Research Project ndiyi dedicate kwababantu balandelayo - abadlale indima enkulu ebomini bam: Umama wam u Nomathemba Princess Willi _ ‘Umamcwerha Ugxarha u Vambane Kasiyoyo Unyangiweyo, ndiyabulela ku mama ngenxaso yakhe nemithandazo, Enkosi Cwerha’. kwakhona kubantwana base khaya u Bukiwe Teisi no Nomaphelo Teisi ndingabalibelanga abatshana bam u Bukho no Amyoli Teisi. Xandigqiba ndibulela u Tata onmcinci wam u Monwabisi Teisi, Enkosi Xhego. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my appreciation to my supervisor Professor Nzewi for mentoring me throughout the process of this research project. If it wasn’t for you this work would have not been achieved, your guidance, constructive criticism and advice towards the success of this project have been helpful. I would like to also express my appreciation to Makana Local Municipality, especially Mrs Roxo Phumza and the Acting Municipal Manager Ms/Mrs Riana Meiring, for assisting me and availing themselves during the course of this study. -

SWARTBOOI, NTLELI GABRIEL 1St Applicant TSOAI

5 IN THE CONSTITUTIONAL COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA CASE NO : In the matter between : SWARTBOOI, NTLELI GABRIEL 1st Applicant TSOAI, GODFREY MOJAKI 2nd Applicant THEDISI, SABATA ELIAS 3rd Applicant MATSEPE, SANAH MOTSHEHOANE 4th Applicant MATUBE, DANIEL NGAKE 5th Applicant PHOLO, JACOB 6th Applicant NDONGA, TSIETSE ANDRIES 7th Applicant LETSHOARA, KHUMISI JOSEPH 8th Applicant MOLETSANE, MOLIFI ERNEST 9th Applicant SWARTBOOI, NTSOKOLO APRIL 10th Applicant MEPHA, MERRIAM PULANE 11th Applicant KGANG, BETHUEL POGISHO 12th Applicant MOLISENYANE, KONTSANE JONAS 13th Applicant MATHIBE, MAKGOBE REGINA 14th Applicant LEKHELEBANE, LIPHAPANG DAVID 15th Applicant MASUMPA, TLANGANISO ISHMAEL 16th Applicant LESEANE, MARTHA DIKELEDI 17th Applicant MOGOJE, THEKO AUBOU 18th Applicant and BRINK, LILIAN RAY 1st Respondent NIEUWOUDT, GERITT 2nd Respondent FOUNDING AFFIDAVIT I, the undersigned, NTLELI GABRIEL SWARTBOOI do hereby make oath and say : 6 1 I am an adult male employed at the Civic Centre, Preller Street, Bothaville. I am the speaker of the Municipality of Nala Local Municipality. I am the First Applicant in this matter. 2 The facts contained herein are within my personal knowledge and are both true and correct. 3 The Second Applicant is GODFREY MOJAKI TSOAI, an adult male Councillor of the Nala Local Municipality who resides at 351 Mpomela Street, Kgotsong, Bothaville. The Second Applicant is also the mayor of the Nala Local Council. 4 The Third Applicant is SABATA ELIAS THEDISI, an adult male Councillor of the Nala Local Municipality who resides at Stand No.3697, Monyakeng, Wesselsbron. 5 The Fourth Applicant is SANAH MOTSHEHOANE MATSEPE, an adult female Councillor of the Nala Local Municipality who resides at 808 Swartbooi Street, Monyakeng, Wesselsbron. -

1 Title&Acknowledgements

University of Pretoria etd – Basson, H M (2005) THE ICONICITY AND LEARNABILITY OF SELECTED PICTURE COMMUNICATION SYMBOLS: A STUDY ON AFRIKAANS-SPEAKING CHILDREN by HESTER MAGDALENA BASSON In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the MASTERS DEGREE IN ALTERNATIVE AND AUGMENTATIVE COMMUNICATION Centre for AAC Faculty of Humanities UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA Pretoria August 2004 University of Pretoria etd – Basson, H M (2005) In loving memory of WILLEM BASSON, (14/06/1984 – 20/08/2002) who taught me to live a day at a time. Met liefdevolle herinneringe aan WILLEM BASSON, (14/06/1984 – 20/08/2002) by wie ek geleer het om een dag op ‘n slag te leef. University of Pretoria etd – Basson, H M (2005) SOLI DEO GLORIA! I would like to thank the following people 1 God for giving me the strength to carry on through three difficult years. 2 Professor Erna Alant and Munyane Mophosho (who was initially involved) for all their support, ideas and patience. 3 The other staff at CAAC for their interest and encouragement. 4 Ms. R. Owen and Dr L. Louw for their help with the statistics. 5 My class, especially Amelia and Michal, who were always willing to listen. 6 Mom and Dad, for your support, patience and prayers and just being there for me. 7 Members of O9 and O12 Cell-groups for your prayers and encouragement. 8 Jaco, for helping with the finishing touches. 9 Gran Hettie, Wim, Tannie Chrissie and Tannie Dolly for all your prayers. 10 All the Myburghs for opening your house to me and allowing me to monopolize your computer. -

Export Directory As A

South African Government Provincial and Local Government Directory 2021-09-27 Table of Contents Provincial and Local Government Directory: Eastern Cape Municipalities ..................................................... 7 Alfred Nzo District Municipality ................................................................................................................................. 7 Amahlathi Local Municipality .................................................................................................................................... 7 Amathole District Municipality .................................................................................................................................. 7 Blue Crane Route Local Municipality......................................................................................................................... 8 Buffalo City Metropolitan Municipality ........................................................................................................................ 8 Chris Hani District Municipality ................................................................................................................................. 8 Dr Beyers Naudé Local Municipality ....................................................................................................................... 9 Elundini Local Municipality ....................................................................................................................................... 9 Emalahleni Local Municipality ................................................................................................................................. -

Annual Report

Promotion of Access to informAtion Act (PAiA) ANNUAL REPORT 2018/2019 i PREFACE The right of access to information has been long recognized in international normative frameworks and has also been provided for in domestic and regional laws. Sections 83 and 84 of the Promotion of Access to Information (PAIA) requires the South African Human Rights Commission (the SAHRC or Commission) to fulfil numerous legislative duties, which includes the tabling of the PAIA annual report with the National Assembly. The report must set out any recommendations made for the ‘development, improvement, modernisation, reform or amendment’ of the PAIA or any other law pertaining to access to information, as well as any recommendations made regarding processes for the electronic disclosure and availability of records. In addition, the report must include a compilation of reports submitted by all public bodies in terms of section 32 of the PAIA. Submission of this public sector compliance report is mandatory for all public bodies in the country. It sets out the number of PAIA requests received by each public body, how many of those requests were granted, denied and transferred; it informs of the number of appeals lodged in terms of PAIA and how many court applications were made. As the analysis contained in this report reveals, compliance levels with the duty to submit such reports remain extremely low. PROMOTION OF ACCESS TO INFORMATION ACT (PAIA) | ANNUAL REPORT 2018/2019 ii FOREWORD The passage of the Promotion of Access to Information Act 2 of 2000 (PAIA) constitutes a crucial tool for the realisation of the constitutional objectives of transparency and open government. -

Seven Get Life

TEL: 057 352 5430/9 OR 084 503 7648, Die Goudveld PRETORUISSTRAAT se keuse Restaurant Accommodation DAGBREEK WELKOM Wednesday Dinner –Chinese/Italian Buffet sedert 1971 since Adults –CR49.95 hildren –u/10 R20.00 TheGoldfields' Sunday Lunch Full Buffet Choice Adults –CR49.95 hildren –u/10 R20.00 Pizza Special (Only Monday-Friday)- Medium R39.95 Wenner van die ATKV-mediaveertjie 2012 vir beste streekkoerant in Suid-Afrika X1QJ67X5-VI100915 TEL (057) 357 1304 DONDERDAG 10 SEPTEMBER 2015 WWW.VISTANEWS.CO.ZA GRATIS Seven Having a look get life Marti Will attacked and stabbed Mathe twice in his back. He managed to flee THE seven gang members who and was taken to the Bongani were caught and convicted for a Hospital for medical treatment, as savage murder they had commit- he was bleeding profusely. ted in 2014 in Kutloanong, have The other friends also fled. each been sentenced to life The group of five Italians and imprisonment. one Hanapuso overpowered In addition, the seven have Sakhumzi Boqwana and cut his each been given three years for throat. They hacked him with assault grievous bodily harm and axes and a garden fork. Boqwana three years for the Prevention of died at the scene. The suspects the Organised Crime Act (gang- fled the scene. The investigation sterism). was assigned to Det.WO Ditaba The accused, Edward Baile Tilo Marumo of the Welkom Cluster (23), Sabata Simon Phejane (24), Murder Task Team. Osama Herman Tsholo (29), The investigator, together with Mulungisi Lincoln Mahloko (24), the Public Order Policing (POP) Promise Johannes Monauna (23), and the Tactical Response Team Molefi Clarens Ralethohlane (23) (TRT), launched a manhunt to and Sibusiso Eddie Mvala (23), trace members of the gangs. -

Provincial Gazette for Free State No 76 of 14-November-2014

Provincial Provinsiale Gazette Koerant Free State Province Provinsie Vrystaat Published by Authority Uitgegee op Gesag NO. 76 FRIDAY 14 NOVEMBER 2014 NO. 76 VRYDAG, 14 NOVEMBER 2014 PROCLAMATION PROKLAMASIE 35 Declaration of Township: Thabong: Extension 19 …………….. 2 35 Dorpsverklaring: Thabong: Uitbreiding 19 ……………...……….. 2 MISCELLANEOUS Applications For Public Road Carrier Permits: Advert 170 …....…….. 5 Advert 172 …………. 44 NOTICE KENNISGEWINGS The Conversion of Certain Rights into Leasehold …………..……….. 99 Wet op die Omskepping van Sekere Regte tot Huurpag ……………. 99 PLEASE TAKE NOTE: THE LAST PUBLICATION OF THE PROVINCIAL GAZETTE FOR THE YEAR 2014 WILL BE ON 12 DECEMBER 2014. THE NEXT PUBLICATION WILL BE ON 16 JANUARY 2015 ...…. 103 PROVINCIAL GAZETTE / PROVINSIALE KOERANT, 14 NOVEMBER 2014 / 14 NOVEMBER 2014 2 PROCLAMATIONS PROKLAMASIES ________ ________ [NO. 35 OF 2014] [NO. 35 VAN 2014] DECLARATION OF TOWNSHIP: THABONG: EXTENSION 19 DORPSVERKLARING: THABONG: UITBREIDING 19 By virtue of the powers vested in me by section 14(1) of the Townships Kragtens die bevoegdheid my verleen by artikel 14(1) van die Ordinance, 1969 (Ordinance No. 9 of 1969), I, S M Mlamleli, Member Ordonnansie op Dorpe, 1969 (Ordonnansie No. 9 van 1969), verklaar of the Executive Council of the Province responsible for Cooperative ek, S M Mlamleli, Lid van die Uitvoerende Raad van die Provinsie Governance, Traditional Affairs and Human Settlements, hereby verantwoordelik vir Samewerkende Regering, Tradisionele Sake en declare the area represented by General Plan S.G. No. 1037/2005 as Menslike Nedersettings, hierby die gebied voorgestel deur Algemene approved by the Surveyor General on 14 November 2005 to be an Plan L.G. No. -

Post 27/55 : Assistant Librarian (X2 Posts) Salary : R208 584

POST 27/55 : ASSISTANT LIBRARIAN (X2 POSTS) SALARY : R208 584 per annum (Level 06), (A basic salary) CENTRE : Phomolong Public Library Ref No: 3513/62 Phiritona Public Library Ref No: 3616/66 REQUIREMENTS : Relevant Diploma in Library and Information Studies/Science (NQF 6) or equivalent and related qualification. Knowledge in library administration, library materials as well a basic management and supervision. Planning .organizing, research skills with ability do to analysis. Basic experience in a library environment will serve as an advantage. DUTIES : Plan, coordinate the services/activities of the library. Establish community structure eg library committees including consultation with such structures. Render professional library and information services eg check books in and out of library, assist variety of users to locate materials and use library resources. Catalogue and shelve library material. Promote the use of libraries and a culture of reading. Perform administrative duties in the Library. Responsible for management of resources eg budget, assets and human resources. ENQUIRIES : Ms Tlaleng Modupe Tel No: (051) 066 479 1443 POST 27/56 : LIBRARY ASSISTANT (X8 POSTS) SALARY : R173 703 per annum (Level 05), (A basic salary) CENTRE : Rouxville Public Library Ref No: 3222/40 Bethlehem Public Library Ref No: 3402/41 Hoopstad Public Library Ref No: 3531/46 Mangaung Public Library Ref No: 3303/52 (X2 Posts) Clocolan Public Library Ref No: 3415/56 Thabong I Public Library Ref No: 3503/59 Riebeeckstad Public Library Ref No: 350/60 Brandfort -

Type Your Document Title Here (Arial 21 Pts, Bold)

Promotion of Access to Information Act Manual Auditor General South Africa February 2012 Promotion of Access to Information Act Manual 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 The right of access to information is entrenched under section 32 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa. Section 32 provides that everyone has the right of access to any information held by state; or held by any other person that is to be used for the protection or exercise of any right. The Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA) is the law that gives effect to Section 32 of the Constitution. This Act is regulated by the South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC), and was approved by Parliament on 2 February 2000 and came into effect on 9 March 2001. 1.2 The purpose of the Act is to promote transparency, accountability and good governance by empowering and educating the public to: understand and exercise their rights, understand the functions and operations of public bodies, and effectively scrutinise and participate in decision-making by public bodies that affect their rights. 1.3 Under the Act, any person can demand records from public and private bodies without showing a reason. Public and private bodies currently have 30 days to respond (reduced from 60 days before March 2003 and 90 days before March 2002) to the request. 1.4 Organisations are required to compile a Manual to serve both as an index of records held by public bodies and as a guide for requesters. The manual describes the procedure to be followed when requesting records. -

Idp Review Process 1

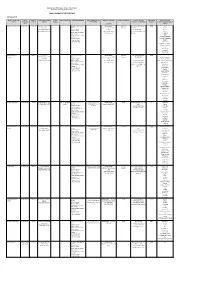

Index INTRODUCTION 1 THE IDP REVIEW PROCESS 1 SITUATIONAL ANNALYSIS 9 - 18 VISION AND MISSION OF NALA MUNICIPALITY 19 DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMS 20 - 36 CAPITAL BUDGET 2006/2007 37 NALA IDP REVIEW 2006/2007 IDP REVIEW PROCESS IN NALA 1. Introduction Nala Local Municipality decided to do its IDP Review in-house with the help of PIMSS CENTRE under the area of Jurisdiction. The roles and responsibilities of the two parties are clearly spelled out. Below is a programme scheduled, compiled by the office of the IDP Manager and the PIMSS CENTRE. Table 2.1: IDP Review Process Plan: Dates of Workshops and Participating Structures ACTIVITY DATE OF PARTIES INVOLVED MEETING OR WORKSHOP Discuss and agree on work schedule with IDP Manager January 2006 Municipal Manager (MM) IDP Manager (IDP M), Chief Financial Officer Introduction to Representative Forum and discuss work schedule February 2006 Representative Forum (RF) Gather, analyse and correlate latest information February 2006 HOD’s and PIMSS CENTRE Revisit sector plans, and the Reviewed IDP document February 2005 RF Update the current status of the LM area February 2005 RF Confirm IDP vision, mission, and priorities February 2005 RF Revisit objectives and strategies February 2005 SC & HOD’s Amend Project list March 2006 SC & HOD’s Review projects and KPI’s against budget March 2006 IDP Steering Committee and Budget Committee Present the draft to the Steering Committee March 2006 MM , IDP Manager & PIMSS CENTRE Circulate Reviewed IDP document March 2006 IDP Manager, PIMSS CENTRE & COUNCIL Incorporate comments for adoption March 2006 IDP Steering Committee & Budgets Final presentation of document to council March 2006 Municipal Manager’s Office Source: Updated during the IDP Review Process – Feb – March 2006 IDP Review means a process whereby the IDP is assessed/evaluated in terms of the municipality’s performance as well as changing circumstances.